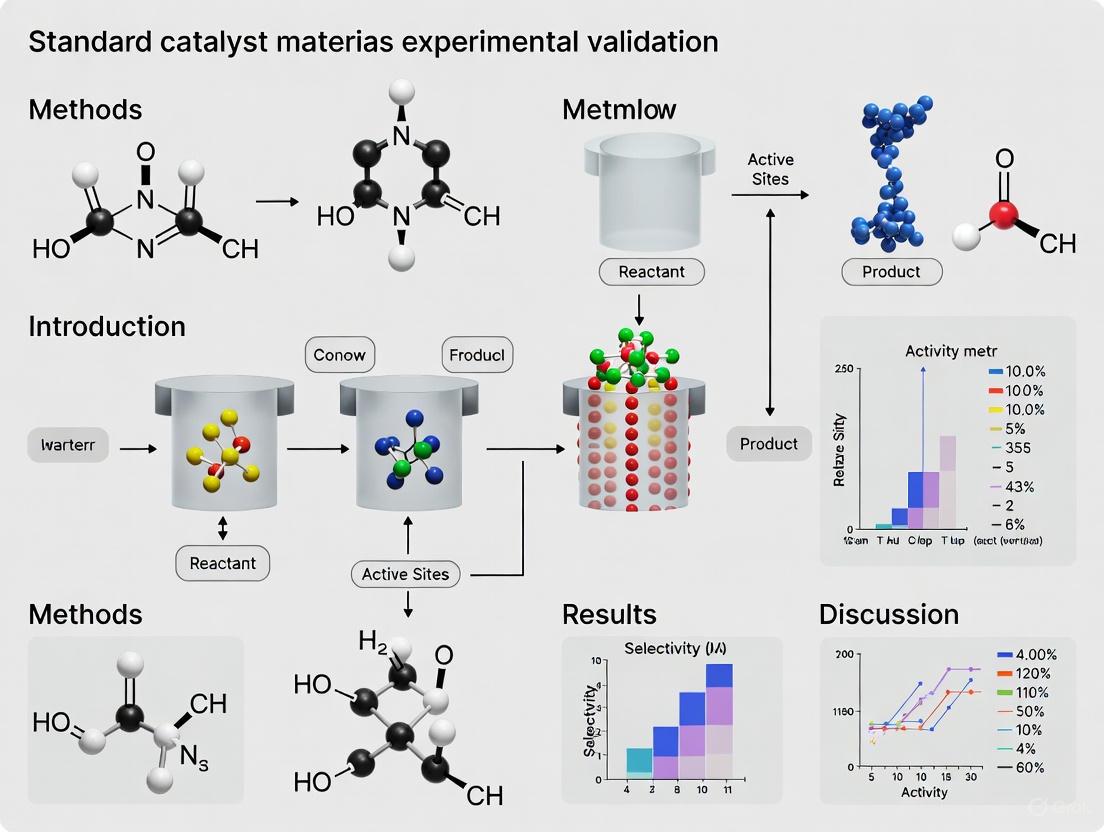

A Researcher's Guide to Standard Catalyst Materials: From Selection to Experimental Validation

This guide provides researchers and scientists with a comprehensive framework for selecting, applying, and validating standard catalyst materials in experimental settings.

A Researcher's Guide to Standard Catalyst Materials: From Selection to Experimental Validation

Abstract

This guide provides researchers and scientists with a comprehensive framework for selecting, applying, and validating standard catalyst materials in experimental settings. It covers foundational principles of industrial catalysts and advanced materials like single-atom and triatomic catalysts, detailing synthesis strategies and characterization techniques such as XPS, XRD, and FTIR. The content also addresses common challenges including catalyst deactivation and poisoning, and outlines robust methodologies for performance comparison and experimental validation, serving as a critical resource for accelerating catalyst development and application in energy and biomedical fields.

Understanding Standard Catalyst Materials: Types, Properties, and Industrial Significance

The Pervasive Role of Catalysts in Modern Industry

Catalysts are indispensable substances that increase the rate of chemical reactions without being consumed in the process, serving as the silent workhorses of modern industrial chemistry [1]. Their ability to lower activation energy, enhance reaction efficiency, and improve product selectivity makes them fundamental to sectors ranging from petrochemicals and pharmaceuticals to environmental protection and emerging clean energy technologies [2] [3]. As industries worldwide face increasing pressure to adopt more sustainable and efficient processes, the role of advanced catalyst materials has become more critical than ever, driving innovation and enabling the transition toward a greener economy.

Market Context and Industrial Impact

The global catalyst market demonstrates robust growth, reflecting its essential role in modern industry. The high-performance catalyst segment specifically is projected to expand from USD 4,212.6 million in 2025 to USD 6,707.3 million by 2035, progressing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.7% [2]. Other market analyses project the broader catalyst market to grow from USD 34.18 billion in 2025 to USD 51.45 billion by 2034, highlighting the significant economic footprint of catalytic technologies [3].

This growth is primarily driven by stringent environmental regulations, the expanding petrochemical industry in Asia-Pacific, and increasing investments in clean energy technologies such as hydrogen production and carbon capture [2] [4] [5]. The industry is simultaneously evolving through technological advancements, including the integration of digital tools like AI and IoT for catalyst design and process optimization, and a stronger focus on developing sustainable, eco-friendly catalytic solutions [2] [5].

Table 1: Global Catalyst Market Outlook (2025-2035)

| Market Segment | 2025 Market Size (Est.) | 2035 Projected Market Size | Projected CAGR | Primary Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Performance Catalysts | USD 4,212.6 million [2] | USD 6,707.3 million [2] | 4.7% [2] | Clean energy solutions, advanced refining tech, environmental regulations [2] |

| Overall Catalyst Market | USD 34.18 billion [3] | USD 51.45 billion by 2034 [3] | 4.65% [3] | Petrochemical demand, environmental standards, pharmaceutical boom [3] |

| Industrial Catalysts | USD 22.53 billion [6] | USD 34.52 billion [6] | 4.82% [6] | Surging petrochemical needs, energy cost optimization, green chemistry [6] |

Standard Catalyst Materials: A Comparative Analysis

For experimental validation and industrial application, catalysts are primarily classified by their physical state and relationship to the reactant phase. The performance of these materials is evaluated based on key parameters: activity (ability to increase reaction rate), selectivity (capacity to produce a desired product over alternatives), and stability (lifetime before deactivation) [1].

Performance Comparison of Major Catalyst Types

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Major Catalyst Types for Experimental Validation

| Catalyst Type | Phase Relationship | Key Performance Metrics | Optimal Industrial Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous | Different phase (typically solid catalyst, liquid/gas reactants) [1] | High surface area, porosity, active site density [1]; Stability under harsh conditions [1] | Petroleum refining [3], chemical synthesis [6], emission control (catalytic converters) [1] | Easy separation/reuse [1], high durability [1], suitable for continuous processes [1] | Mass transfer limitations [1], potential surface fouling/sintering [1] |

| Homogeneous | Same phase (typically in liquid solution) [1] | High selectivity [1]; Precise reaction control [1] | Pharmaceutical synthesis [1], fine chemicals [1], specialty polymer production [2] | High selectivity/control [1]; Mild operating conditions [1] | Difficult separation/recovery [1]; Limited stability [1] |

| Biocatalysts | Typically aqueous phase [1] | Exceptional substrate & reaction specificity (e.g., enantioselectivity) [1] | Pharmaceutical synthesis [4] [3], food processing [3], biofuel production [3] | High selectivity [1]; Green & sustainable profile [1]; Mild reaction conditions [1] | Sensitivity to temperature/pH [1]; Limited operational window [1] |

| Nanocatalysts | Varies (often heterogeneous) | Maximized surface-to-volume ratio; Tunable electronic properties [1] | Energy conversion [1], electrocatalysis [7], environmental remediation [7] | High activity [1]; High surface area [1] | Complex synthesis [1]; Scale-up challenges [1] |

Emerging Catalyst Materials

The field is advancing with several novel materials designed to overcome the limitations of traditional catalysts:

- Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs): These feature individual metal atoms dispersed on a support, maximizing atom efficiency and providing uniform active sites, often leading to exceptional catalytic properties [1].

- Heterogenized Homogeneous Catalysts: These materials aim to bridge the gap between homogeneous and heterogeneous types by immobilizing molecular catalytic complexes onto solid supports, combining high selectivity with easy separation [1].

- Advanced Material Composites: Research continues into sophisticated structures such as the

MnFe2O4/Claycomposite, which has shown high efficiency (complete dye degradation within 120-150 minutes) in catalytic wet peroxide oxidation for wastewater treatment [7].

Experimental Validation and Benchmarking

Robust experimental validation is crucial for developing and deploying effective catalysts. The introduction of community-based benchmarking databases like CatTestHub represents a significant step toward standardizing data reporting in heterogeneous catalysis [8]. This open-access database, designed according to FAIR principles, provides a platform for comparing catalytic activity against standardized materials and agreed-upon reaction conditions, addressing the long-standing challenge of defining "state-of-the-art" in the field [8].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Catalytic Activity Testing (Microreactor Systems)

Objective: To measure the intrinsic activity, selectivity, and stability of a solid catalyst for a gas-phase reaction, free from heat and mass transfer limitations [8].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions:

- Catalyst Bed: The solid catalyst, often pelletized, crushed, and sieved to a specific particle size (e.g., 150-300 μm) to minimize internal diffusion limitations [8].

- Reaction Gases: High-purity reactant gases (e.g., H₂, N₂, O₂) and diluents, controlled by mass flow controllers [8].

- Vapor Delivery System: For liquid reactants (e.g., methanol), a vaporization system is used to introduce a precise concentration into the gas stream [8].

- Analytical Instrumentation: Online Gas Chromatograph (GC) equipped with appropriate detectors (FID, TCD) for separating and quantifying reaction products at steady-state conditions [8].

Workflow:

Experimental Workflow for Catalyst Testing

Protocol for Catalyst Characterization (Temperature-Programmed Reduction - TPR)

Objective: To probe the reducibility and metal-support interactions of a catalyst, which are critical indicators of its potential activity [7].

Workflow:

Temperature-Programmed Reduction (TPR) Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Catalytic Experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimentation | Exemplary Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Supported Metal Catalysts (e.g., Pt/SiO₂, Pd/C) | Benchmark materials for oxidation, hydrogenation, and decomposition reactions; provide well-defined active sites [8]. | Methanol decomposition to syngas; benchmark activity in databases like CatTestHub [8]. |

| Zeolites (e.g., H-ZSM-5) | Solid acid catalysts with shape-selective properties due to their microporous crystalline structure [8]. | Acid-catalyzed reactions like cracking, isomerization, and alkylation [1]. |

| Metal Oxide Catalysts (e.g., Al₂O₃, CeO₂, ZrO₂) | Used as catalyst supports or active phases for redox reactions; provide thermal stability and oxygen storage capacity [7]. | Support for Ni in methane partial oxidation [7]; key component in automotive three-way catalysts. |

| Organometallic Complexes (e.g., Rh-based, Pd-based) | Serve as homogeneous catalysts or precursors for heterogeneous systems; enable precise molecular-level design [1]. | Asymmetric hydrogenation in pharmaceutical synthesis; carbon-carbon cross-coupling reactions [1]. |

| Gaseous Reactants (e.g., H₂, CO, O₂, N₂) | Core reactants and diluents for gas-phase catalytic testing; purity is critical to avoid catalyst poisoning [8]. | Feedstock for hydroprocessing, syngas reactions, ammonia synthesis, and oxidation catalysis [8]. |

Catalyst Selection Logic and Future Directions

Selecting the appropriate catalyst is a multi-factorial decision that depends on the specific reaction, process economics, and sustainability goals. The following logic framework outlines the primary selection pathway for researchers.

Decision Logic for Catalyst Type Selection

The future of industrial catalysis is being shaped by several powerful trends. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning is dramatically accelerating the discovery and optimization of new catalytic materials by analyzing vast datasets to predict catalytic activity and guide experimental work [5]. Furthermore, the push for sustainability is driving the development of biodegradable and renewable catalysts for green manufacturing, alongside advanced materials for carbon capture and utilization and the hydrogen economy, where catalysts are essential for efficient production, storage, and use of hydrogen as a clean energy carrier [9] [5].

In the realm of industrial chemistry and pharmaceutical development, catalysts are indispensable for enabling efficient, selective, and sustainable chemical processes. Their performance is quantitatively assessed through three fundamental properties: activity, selectivity, and stability. Activity measures the rate at which a catalyst accelerates a reaction, determining process efficiency and reactor sizing. Selectivity defines the catalyst's ability to direct reaction pathways toward desired products while minimizing byproducts, crucial for yield optimization and waste reduction. Stability refers to the catalyst's ability to maintain its performance over time, resisting deactivation mechanisms such as sintering, poisoning, and coking, which directly impacts process economics and operational continuity [10] [11].

Understanding the intricate balance and potential trade-offs between these properties is essential for selecting and designing catalysts for specific applications, particularly in pharmaceutical synthesis where precision and reproducibility are paramount. This guide provides an objective comparison of catalyst performance across these key properties, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to research-scale validation.

Quantitative Comparison of Catalyst Performance

The following tables summarize experimental data for different catalyst systems, highlighting the relationship between their physicochemical characteristics and their activity, selectivity, and stability performance.

Table 1: Comparison of Activity and Selectivity in Model Reactions

| Catalyst System | Reaction | Activity (Specific Rate) | Selectivity to Desired Product | Key Performance Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PdCuNi Medium Entropy Alloy Aerogel [12] | Formic Acid Oxidation | 2.7 A mg⁻¹ | Not Specified | Mass activity 6.9x higher than commercial Pd/C |

| Pt/CeO₂ (Conventional, CO-treated) [13] | CO Oxidation | 0.099 s⁻¹ | Not Specified | High initial activity, but deactivates in O₂-rich streams |

| Pt/CeO₂ (V-pocket stabilized) [13] | CO Oxidation | ~40x K-Pt@MFI (steady state) | Not Specified | Breaks activity-stability trade-off; maintains high activity |

| Pt-Sn/Al₂O₃ (Promoted) [11] | C₁₀-C₁₄ Paraffin Dehydrogenation | Decreasing with TOS | Increases with TOS (~90%) | Typical trade-off: selectivity increases as activity decays |

Table 2: Catalyst Stability and Lifetime Analysis

| Catalyst System | Deactivation Mechanism | Lifetime / Stability Assessment | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pt/CeO₂ (Conventional) [13] | Oxidative fragmentation to less active PtOₓ | Severe deactivation in O₂-rich streams | High-temperature, excess O₂ |

| Pt-Sn/Al₂O₃ (Industrial) [11] | Coking, Sintering | 40-60 days (industrial operation) | 475-490°C, 0.1-0.25 MPa |

| K-Pt@MFI Zeolite [13] | Avoids oxidative fragmentation | High stability, lower initial activity | O₂-rich CO atmospheres |

| PdCuNi MEA Aerogel [12] | Not Specified | High durability implied by fuel cell performance | Acidic solvent, fuel cell operation |

Experimental Protocols for Catalyst Evaluation

Accelerated Deactivation Testing

For long-lived industrial catalysts, predicting lifetime is a major challenge. Accelerated deactivation tests are used to compare performance and screen catalysts more economically than full-life testing. Key methodologies include:

- Principle: Increase the deactivation rate by manipulating parameters like contact time (lower space velocity) or temperature, while ensuring the deactivation mechanism mirrors that under normal operation [11].

- Procedure:

- Parameter Selection: Identify the primary cause of deactivation (e.g., coking, sintering). The accelerating parameter should target this specific cause.

- Bench-Scale Reactor Setup: Conduct tests in lab or bench-scale reactors with careful control of temperature, pressure, and feed composition.

- Kinetic Modeling: Monitor activity and selectivity over time. Fit the data to kinetic models (e.g., separable kinetics where the deactivation rate is independent of the main reaction rate) to extract deactivation rate constants.

- Model Validation: Validate the model and predicted lifetime against short-term runs under normal operating conditions [11].

Electrochemical Activity Measurement (Formic Acid Oxidation)

This protocol is used to evaluate the activity of electrocatalysts, such as the PdCuNi alloy, for reactions relevant to fuel cells.

- Objective: To determine the mass activity of a catalyst for the formic acid oxidation reaction (FOR) [12].

- Procedure:

- Catalyst Ink Preparation: Disperse the catalyst powder in a solvent (e.g., a water-alcohol mixture) with a binder (e.g., Nafion) to form a homogeneous ink.

- Electrode Preparation: Deposit a precise volume of the ink onto a clean glassy carbon electrode, resulting in a known catalyst loading (e.g., 0.5 mg cm⁻²).

- Electrochemical Cell Setup: Use a standard three-electrode setup (catalyst as working electrode, Pt wire as counter electrode, and a reference electrode like Ag/AgCl) in an electrolyte containing formic acid.

- Data Acquisition: Perform cyclic voltammetry, scanning the potential and measuring the resulting current.

- Data Analysis: The mass activity (in A mg⁻¹) is calculated by normalizing the current generated at a specific potential by the total mass of the active metal (e.g., Pd) on the electrode [12].

CO Oxidation Activity Measurement

This is a common test reaction for comparing catalyst activity.

- Objective: To measure the rate of CO oxidation over a solid catalyst like Pt/CeO₂ [13].

- Procedure:

- Reactor System: A fixed-bed flow reactor is typically used.

- Feed Composition: A stream containing a specific ratio of CO, O₂, and an inert balance gas (e.g., He) is passed over the catalyst bed.

- Pre-treatment: The catalyst is often pre-treated (e.g., in CO at 300°C) to reduce the metal and create active sites.

- Activity Measurement: The temperature is raised, and the conversion of CO is measured (e.g., via gas chromatography). The activity is reported as a turnover frequency (TOF in s⁻¹) – the number of CO molecules converted per active site per second – or as the temperature required for 50% conversion (T₅₀) [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Catalyst Research and Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Validation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gamma Alumina (γ-Al₂O₃) Support | High-surface-area support for dispersing active metals. | Common support for Pt-Sn dehydrogenation catalysts [11]. |

| Ceria (CeO₂) Support | Redox-active support that provides oxygen storage capacity and stabilizes metal atoms. | Support for highly active Pt CO oxidation catalysts [13]. |

| Metal Precursors (e.g., H₂PtCl₆, SnCl₂) | Source of active and promoter metals during impregnation synthesis. | Preparation of promoted Pt-based catalysts [11]. |

| Sodium Borohydride (NaBH₄) | Strong reducing agent for synthesizing metal nanoparticles and alloys. | One-pot reduction synthesis of PdCuNi medium entropy aerogel [12]. |

| Zeolites (e.g., MFI, CHA) | Microporous, acidic supports with shape-selective properties. | Used as a non-reducible support for K-Pt clusters in CO oxidation [13]. |

Logical Workflow for Catalyst Design and Validation

The following diagram illustrates a modern, integrated approach to designing and validating high-performance catalysts, which combines computational and experimental methods to efficiently navigate complex material spaces.

Diagram: Integrated catalyst design and validation workflow, combining computational screening with experimental testing.

The effective application of industrial catalysts in research and development hinges on a rigorous, multi-faceted evaluation of activity, selectivity, and stability. As demonstrated by the cited data, high initial activity can be compromised by poor stability, as seen in conventional Pt/CeO₂ systems, while a singular focus on stability may sacrifice performance. Advanced catalyst systems, such as structure-stabilized Pt/CeO₂ or multicomponent alloy aerogels, demonstrate that this trade-off can be overcome through intelligent design [12] [13]. The integration of computational tools like DFT and machine learning with traditional experimental methods is proving to be a powerful strategy for accelerating the discovery of such high-performance catalysts. For researchers, a systematic approach that employs standardized activity tests, accelerated stability protocols, and a deep understanding of the underlying deactivation mechanisms is essential for the reliable selection and development of catalyst materials for pharmaceutical synthesis and other precision chemical processes.

This guide provides an objective comparison of three principal classes of solid catalysts—Precious Metals, Transition Metals, and Solid Acid Supports—for researchers engaged in experimental validation and process development. The selection of a benchmark catalyst is critical for optimizing reaction efficiency, cost, and sustainability. The following data-driven analysis synthesizes performance metrics, operational characteristics, and application suitability to inform material selection. Key differentiators include catalytic activity, stability, resistance to deactivation, and economic feasibility, with the optimal choice being highly dependent on the specific reaction environment and process goals.

Table 1: High-Level Catalyst Classification and Characteristics

| Catalyst Class | Example Materials | Primary Strength | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precious Metals | Pt, Pd, Rh, Ru [14] [15] | High intrinsic activity & stability [14] | Hydrogenation, fuel cells, emission control [16] [15] |

| Transition Metals | Fe, Co, Ni, Cu [17] [18] | Cost-effectiveness & promotional effects [17] | CO₂ conversion, biomass pyrolysis, NOx reduction [18] |

| Solid Acid Supports | Zeolites, Alumina, Silica [16] [19] | Shape selectivity & tunable acidity [18] | Cracking, isomerization, alkylation [19] |

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative benchmarking reveals distinct performance profiles for each catalyst class, guided by their inherent chemical properties and economic considerations.

Table 2: Catalyst Performance and Economic Benchmarking

| Parameter | Precious Metals | Transition Metals | Solid Acid Supports |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Market Size (2024/2025) | ~USD 61.11 Billion (2024) [15] | N/A (Wide dispersion) | ~USD 50.8 Million (2025 Est.) [19] |

| Projected CAGR | 10.3% (2025-2037) [15] | N/A | ~4% (2025-2033) [19] |

| Key Market Driver | Stringent emission regulations [15] | Green chemistry & sustainability [18] | Demand for eco-friendly processes [19] [20] |

| Relative Cost | Very High [16] [15] | Low to Moderate [18] | Low to Moderate [19] |

| Selectivity | Very High [14] | Moderate to High [18] | High (Shape-selective) [18] |

| Stability | Excellent (High melting point, corrosion-resistant) [14] | Moderate (Prone to oxidation/sintering) [21] | High (Thermally stable) [18] |

| Common Deactivation Modes | Poisoning (e.g., by Lead, Sulfur) [17] | Coke deposition, sintering [21] | Coke deposition, dealumination [21] |

Detailed Catalyst Profiles and Experimental Data

Precious Metal Catalysts (PMs)

Precious metal catalysts, characterized by atoms with d-electrons in their outermost layers, exhibit exceptional selectivity, synergism, and stability [14]. Their high activity stems from the ability to easily form covalent bonds with reactants like oxygen and hydrogen, lowering energy barriers for redox processes [14]. A critical application is in Three-Way Catalysts (TWCs) for automotive emission control, where Pd is often the active component for oxidizing CO and hydrocarbons [17]. Experimental studies show that promoting Pd with transition metals can significantly enhance performance.

Table 3: Experimental Data on Transition Metal-Promoted Pd Catalysts [17]

| Catalyst Formulation | Light-Off Temperature (T50%) | Oxygen Storage Capacity | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pd/Ce₀.₆₇Zr₀.₃₃O₂ (Pd/CZ) | Baseline | Baseline | Base performance metric. |

| Pd/CZFe | Lowest | Highest | Fe incorporation creates homogeneous mixed oxides, enhancing oxygen mobility and catalytic activity most effectively. |

| Pd/CZCo | Very Low | Very High | Performance comparable to Pd/CZFe; Co acts as an excellent promoter. |

| Pd/CZCr | Highest | Lowest | Forms less homogeneous mixed oxides, resulting in the least catalytic improvement. |

Experimental Protocol (Catalytic Testing for TWCs) [17]:

- Reactor System: Use a fixed-bed quartz reactor operating at atmospheric pressure.

- Feed Gas Composition: Simulate automotive exhaust with a mixture of CO, NO, C₃H₆, O₂, H₂, and balance N₂.

- Procedure:

- Load catalyst sample (e.g., 100 mg) into the reactor.

- Pre-treat the catalyst in a flow of 10% O₂/N₂ at 500°C for 30 minutes.

- Cool to desired starting temperature (e.g., 100°C).

- Introduce the reactant gas mixture at a defined space velocity (e.g., 40,000 h⁻¹).

- Heat the reactor at a controlled ramp rate (e.g., 10°C/min) while monitoring effluent composition with a mass spectrometer or gas chromatograph.

- Data Analysis: Calculate conversion rates for CO, NO, and hydrocarbons. The light-off temperature (T50%) is reported as the temperature required for 50% conversion of a specific pollutant.

Transition Metal Catalysts (TMs)

Supported transition metal catalysts are pivotal for sustainable and cost-effective processes like CO₂ conversion and biomass valorization [18]. Their activity is often derived from their ability to form metal nanoparticles or isolated ions on high-surface-area supports, with zeolites being a prominent example due to their ion-exchange capacity and shape selectivity [18].

Table 4: Applications of Transition Metals Supported on Zeolites (TM/Z) [18]

| Industrial Process | Relevant Transition Metals | Zeolite Support(s) | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO₂ Conversion | Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Ru, Rh, Pt | MFI, BEA, CHA | Hydrogenation of CO₂ to fuels/chemicals. |

| SCR-deNOx | Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Ag | MOR, BEA, MFI, CHA | Selective catalytic reduction of NOx with ammonia. |

| Biomass Pyrolysis | Ga, Ni, Co, Rh | ZSM-5, Y, β | Deoxygenation and upgrading of bio-oil. |

| Hydrogen Production | Ru, Pt, Rh, Pd, Co, Ni | ZSM-5, Y, BEA | Reforming of biomass-derived oxygenates. |

Experimental Protocol (Synthesis of TM/Z via Ion Exchange) [18]:

- Objective: To incorporate transition metal ions (e.g., Cu²⁺, Fe³⁺) into a zeolite framework (e.g., ZSM-5) to create active sites.

- Procedure:

- Dissolve a salt of the target transition metal (e.g., Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O) in deionized water.

- Add the zeolite support to the solution, maintaining continuous stirring to create a slurry.

- Heat the slurry at 70-80°C for 12-24 hours to facilitate ion exchange.

- Filter the solid product and wash thoroughly with deionized water to remove excess ions.

- Dry the catalyst overnight at 100-120°C.

- Calcinate the dried material in static air or a flowing gas (e.g., 500°C for 5 hours) to convert the metal salts into their active oxide forms.

Solid Acid Supports

Solid acid catalysts function primarily through surface acidity, enabling carbocation-mediated reactions such as cracking and isomerization. Zeolites are the most prominent class, with their activity and selectivity governed by framework topology (e.g., MFI, FAU), Si/Al ratio (acidity), and porosity [18]. A key advantage is their shape-selectivity, where the microporous structure controls access of reactants to active sites and the diffusion of products [18]. Beyond zeolites, other supports like alumina, silica, and carbon are widely used, with alumina being dominant in the supported precious metal catalyst market due to its superior properties and cost-effectiveness [16].

Catalyst Deactivation and Regeneration Pathways

Catalyst deactivation is an inevitable challenge in industrial processes. The primary mechanisms include:

- Coking/Carbon Deposition: The formation and deposition of carbonaceous materials, blocking active sites and pores [21].

- Poisoning: Strong chemisorption of species (e.g., sulfur, lead) on active sites, rendering them inactive [17].

- Thermal Degradation/Sintering: Loss of active surface area due to exposure to high temperatures [21].

- Mechanical Damage: Physical breakdown of catalyst particles [21].

Regeneration strategies are crucial for restoring activity and ensuring economic viability. While coke deposition is often reversible through controlled oxidation, poisoning can be irreversible [21]. The following workflow outlines the logical process for diagnosing deactivation and selecting a regeneration strategy.

Diagram: Catalyst Deactivation Diagnosis and Regeneration Workflow. This diagram outlines the logical process for identifying the cause of catalyst deactivation and selecting an appropriate regeneration pathway, highlighting that only coke deposition is typically fully reversible [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Essential Materials for Catalyst Synthesis and Testing

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Zeolite Supports (e.g., ZSM-5, BEA, FAU) | Provide acidic sites & shape-selective microporous structure [18] | Si/Al ratio: 10-500, Surface Area: 300-500 m²/g |

| Metal Oxide Supports (γ-Al₂O₃, SiO₂, CeZrO₂) | High surface area supports for dispersing active metals [16] [17] | Surface Area: 100-300 m²/g, Pore Volume: 0.5-1.0 cm³/g |

| Precious Metal Precursors | Source of active metal phase during catalyst synthesis [14] | H₂PtCl₆, Pd(NO₃)₂, RhCl₃ |

| Transition Metal Precursors | Cost-effective active phase for redox reactions [18] | Ni(NO₃)₂, Co(NO₃)₂, Cu(NO₃)₂, Fe(NO₃)₃ |

| Fixed-Bed Reactor System | Bench-scale testing under continuous flow conditions [14] | Temperature: RT-1000°C, Pressure: Vacuum to 100 bar |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) / Mass Spectrometer (MS) | Online analysis of reaction products and conversion [17] | TCD/FID detectors, Capillary columns |

| Surface Area & Porosity Analyzer | Textural characterization (BET surface area, pore volume) [17] | N₂ physisorption at 77 K |

The benchmark analysis underscores that no single catalyst class is universally superior. Precious metal catalysts offer unparalleled activity and durability for high-value applications like pharmaceuticals and emission control but at a significant cost [14] [15]. Transition metal catalysts provide a versatile and economical platform for emerging sustainable processes, especially when supported on advanced materials like hierarchical zeolites [18]. Solid acid supports, particularly zeolites, remain indispensable for shape-selective petrochemical transformations [19] [18].

Future research directions are focused on enhancing catalyst longevity through advanced regeneration technologies like microwave-assisted and plasma-assisted regeneration [21], and designing next-generation materials such as single-atom catalysts and bimetallic alloys to maximize atom efficiency and synergistic effects [14] [22]. The integration of AI and machine learning for catalyst design and process optimization is also poised to accelerate the discovery of novel catalytic systems [20].

The field of catalysis has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the precise engineering of active sites down to the atomic level. This evolution from nanoparticles to single-atom catalysts (SACs) and subsequently to multi-atom centers represents a paradigm shift in materials design for catalytic applications. While traditional catalysts utilize metal nanoparticles with limited atomic utilization efficiency, atomic-scale catalysts maximize the usage of every metal atom, significantly enhancing catalytic performance while reducing material costs, particularly when employing precious metals [23] [24]. The sequential development from SACs to diatomic catalysts (DACs) and more recently to triatomic catalysts (TACs) has enabled increasingly sophisticated control over reaction pathways through tailored active sites.

Single-atom catalysts, first formally introduced in 2011, feature isolated metal atoms anchored on support materials, achieving theoretical 100% atomic utilization [25] [24]. Despite their maximized efficiency, SACs exhibit constrained tunability in modulating the adsorption energetics of reaction intermediates and face limitations in multi-step complex reactions [23]. Diatomic catalysts address these constraints through bimetallic synergistic effects, where two adjacent metal atoms provide additional active sites and enhanced reaction synergy [23] [26]. The most recent advancement, triatomic catalysts, further expands these capabilities through multi-active-site cooperativity with unique electronic delocalization, breaking the limitations of single and dual-atom systems for complex multi-electron reactions [25].

This comparison guide objectively examines the structural characteristics, experimental performance metrics, and appropriate applications for these three catalyst classes within the broader context of standard catalyst materials for experimental validation research. By providing structured comparative data and detailed methodologies, we aim to equip researchers with the necessary foundation for selecting and validating appropriate atomic-scale catalysts for specific applications across energy, environmental, and biomedical domains.

Comparative Structural Properties and Active Sites

The fundamental differences among SACs, DACs, and TACs lie in the number of atoms at the active sites and their coordination environments, which directly govern their catalytic properties and applications. These structural variations create distinct electronic configurations that ultimately determine their interaction with reactants and catalytic efficiency.

Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) feature isolated metal atoms stabilized on various support materials through coordination with heteroatoms such as nitrogen, oxygen, or sulfur. The most common configuration is the M-N₄ structure, where a single transition metal atom (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni, Cu) is coordinated with four nitrogen atoms embedded in a carbon matrix [24] [27]. This well-defined, uniform structure provides high atomic utilization and exceptional selectivity for simple reactions but limited flexibility for complex multi-step reactions due to the singular nature of the active site.

Diatomic Catalysts (DACs) incorporate two adjacent metal atoms that can be homonuclear (same element) or heteronuclear (different elements). These pairs are typically stabilized in configurations such as M₁M₂N₈, where the two metal atoms share bridging nitrogen atoms within a carbon support [23]. The proximity of the two atoms creates synergistic effects that optimize the adsorption of reaction intermediates and lower activation energy barriers. For example, in Mn(Mn)N₈@BPN and (Mn)NiN₈@BPN diatomic catalysts, the bimetallic synergy enables remarkable OER/ORR overpotentials of 0.084/0.129 V and 0.113/0.178 V respectively, significantly surpassing noble metal benchmarks [23].

Triatomic Catalysts (TACs) represent the next evolutionary step, featuring three metal atoms arranged in linear or triangular configurations. These systems exhibit even greater complexity with multi-active-site cooperativity and enhanced electronic delocalization [25]. A prominent example is the Fe₂/Co-NHCS structure, where a CoN₄ site is positioned adjacent to a dual-atom Fe₂N₅ site, creating a tri-atomic structure that optimizes the spin state of the Fe-Fe double atomic pairs from low to medium spin configuration [28]. This precise electronic engineering enables exceptional performance in oxygen reduction reaction with a half-wave potential of 0.92 V, maintaining functionality even at -40°C for zinc-air batteries [28].

Table 1: Comparative Structural Properties of Atomic-Scale Catalysts

| Structural Feature | Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) | Diatomic Catalysts (DACs) | Triatomic Catalysts (TACs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Site Composition | Isolated single metal atoms | Two adjacent metal atoms | Three metal atoms in linear or triangular configurations |

| Coordination Environment | Typically M-N₄, M-Oₓ | M₁M₂N₈, M-N-M/NC | Multi-atom clusters (e.g., Fe₂N₅+CoN₄) |

| Metal Utilization | ~100% | High, with synergistic effects | High, with multi-site cooperativity |

| Electronic Properties | Single metal center, limited tunability | Diatomic synergy, optimized d-band center | Multi-site electronic delocalization, spin state regulation |

| Typical Support Materials | N-doped carbon, metal oxides, graphene | N-doped carbon, biphenylene (BPN), graphene | Carbon-based materials, MOF derivatives |

| Structural Advantages | Maximized atomic efficiency, uniform sites | Enhanced intermediate adsorption, additional active sites | Dynamic stability, anti-aggregation, complex reaction handling |

Performance Comparison Across Applications

The structural evolution from single to multiple atom active sites has enabled progressively enhanced catalytic performance across diverse applications. Quantitative experimental data reveals distinct advantages for each catalyst class depending on the specific reaction requirements and operating conditions.

Oxygen Reduction/Evolution Reactions (ORR/OER)

In energy conversion reactions, DACs and TACs demonstrate superior performance compared to SACs and traditional benchmarks. Experimental studies on TM₁TM₂N₈@BPN diatomic catalysts show breakthrough bifunctional performance, with Mn(Mn)N₈@BPN and (Mn)NiN₈@BPN achieving remarkably low OER/ORR overpotentials of 0.084/0.129 V and 0.113/0.178 V respectively. These values not only surpass noble-metal benchmarks (RuO₂ and IrO₂) but also outperform conventional Fe-Co and Mn-Fe diatomic catalysts [23]. The exceptional performance originates from optimized intermediate adsorption enabled by Mn-Mn/Mn-Ni synergistic effects and enhanced charge redistribution in the diatomic structure.

Triatomic catalysts further advance ORR performance, particularly under challenging conditions. The Fe₂/Co-NHCS TAC achieves a high half-wave potential of 0.92 V, and when implemented in zinc-air batteries, delivers a peak power density of 271 mW cm⁻² with specific capacity of 806 mAh g⁻¹Zn [26] [28]. Remarkably, these catalysts maintain functionality at subzero temperatures, with flexible Zn-air batteries powered by Fe₂/Co-NHCS delivering 57.3 mW cm⁻² and maintaining charge-discharge stability over 150 cycles at -40°C [28]. This performance stems from spin state optimization, where the adjacent CoN₄ site modulates the spin state of Fe-Fe double atomic pairs to medium spin with t₂g⁴eg¹ 3d-electron configuration, facilitating stronger binding with oxygen reactants.

Carbon Dioxide Reduction Reaction (CO₂RR)

Single-atom catalysts exhibit notable efficacy in CO₂ reduction, particularly when their coordination environment is optimized. A self-healing Cu single-atom catalyst demonstrated remarkable performance for CO₂-to-CH₄ conversion, achieving Faradaic efficiency of 87.06% at -500 mA cm⁻² and 80.21% at -1000 mA cm⁻² after reconstruction from CuN₄ to CuN₁O₂ coordination [29]. This represents a threefold and tenfold improvement respectively compared to the pristine CuN₄ structure. The dynamic reconstruction was triggered by partial cleavage of Cu-N bonds via hydrogen evolution reaction, forming coordinatively unsaturated Cu sites that spontaneously bonded with adjacent ZrO₂ clusters, creating the optimized hybrid Cu-N/O structure.

Diatomic catalysts offer additional advantages for complex CO₂ reduction pathways toward multi-carbon products. The dual metal sites can work cooperatively to activate different reaction intermediates simultaneously, enabling more efficient C-C coupling compared to single-atom sites. While SACs typically excel at two-electron reduction to CO or formate, DACs show promise for deeper reduction to valuable C₂+ products through their ability to optimize adsorption of multiple intermediates at the different metal sites [27].

Biomedical Applications

In biomedical contexts, diatomic nanozymes (DANs) demonstrate significantly enhanced enzyme-mimicking activities compared to single-atom analogues. These materials leverage synergistic interactions between contiguous metal centers to achieve catalytic efficiencies that surpass natural enzymes in some cases. For instance, Fe₂NC DANs supported on ZIF-8 derived N-doped carbon exhibit over 100-fold increased activity in superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and oxidase (OXD)-like activities compared to natural enzymes, enabling applications in protecting against cerebral ischemic reperfusion injury [30].

Similarly, Zn/Mo DSAC-SMA DANs supported on macroscopic aerogel demonstrate over 100-fold peroxidase-like activity enhancement, making them exceptionally effective for biosensing applications [30]. The paired metal atoms in these systems create unique catalytic sites that enhance both activity and specificity, with metal loading ratios typically ranging from 0.11-8.01 wt% depending on the specific metal pairs and support materials.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Atomic-Scale Catalysts in Key Applications

| Application | Catalyst Type | Performance Metrics | Reference/System |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORR/OER | Diatomic Catalysts | OER/ORR overpotentials: 0.084/0.129 V (Mn-Mn), 0.113/0.178 V (Mn-Ni) | Mn(Mn)N₈@BPN, (Mn)NiN₈@BPN [23] |

| ORR | Triatomic Catalysts | Half-wave potential: 0.92 V; Zn-air battery peak power: 271 mW cm⁻² | Fe₂/Co-NHCS [26] [28] |

| CO₂ to CH₄ | Single-Atom Catalysts | Faradaic efficiency: 87.06% @ -500 mA cm⁻²; 80.21% @ -1000 mA cm⁻² | Self-healing CuN₁O₂ [29] |

| Low-Temperature ZAB | Triatomic Catalysts | Peak power density: 57.3 mW cm⁻² @ -40°C; 150 cycle stability | Fe₂/Co-NHCS [28] |

| Enzyme Mimicking | Diatomic Nanozymes | 100x SOD/CAT/OXD-like activity; 23x POD-like activity | Fe₂NC DANs [30] |

| NO Reduction | Single-Atom Catalysts | 100% NO conversion @ 250°C; 100% N₂ selectivity | Fe₁/CeO₂-Al₂O₃ [24] |

Experimental Validation Methodologies

Computational Screening and Design

First-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) provide the foundational methodology for designing and screening atomic-scale catalysts. Standard protocols involve using software packages like VASP with PAW pseudopotentials and PBE functionals. For DACs and TACs, the DFT+U approach corrects for self-interaction errors in transition metal electrons, while van der Waals interactions are captured using the DFT-D3 method [23]. These calculations predict formation energies to assess stability, with negative values indicating thermodynamically favorable structures, and compute adsorption energies of key reaction intermediates to determine activity trends.

Machine learning has emerged as a powerful accelerator for catalyst discovery, particularly valuable for navigating the vast design space of multi-atom catalysts. In one representative approach for diatomic ORR catalysts, researchers constructed a catalytic "hot spot map" using two primary descriptors: the geometric distance between diatomic pairs and the electronic magnetic moment [26]. Through gradient boosting regression (GBR) algorithms trained on DFT-calculated overpotentials, they identified Co-N-Mn/NC as an ideal catalyst from 121 possible combinations, with the ML predictions achieving an average error of only 0.03 V compared to subsequent experimental validation [26].

Natural language processing (NLP) techniques offer an alternative screening approach, as demonstrated for single-atom catalysts in Na-S batteries. By transforming scientific literature into high-dimensional embeddings using models like GPT-4o, researchers identified magnetic metal centers (particularly Fe and Co) as optimal for sulfur reduction reactions, guided by the frequency analysis of TOP-30 nearest neighbor papers in the embedded space [31].

Synthesis and Characterization Protocols

Synthesis Methods: Atomic-scale catalysts typically employ bottom-up approaches using metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) or other porous templates as precursors. For example, ZrO₂/CuN₄ composite SACs are synthesized through pyrolysis of PCN-222(Cu) MOF at 800°C under inert atmosphere, preserving the hollow nanotube morphology while creating atomically dispersed Cu sites [29]. DACs and TACs often utilize co-embedding strategies where dual or triple metal precursors are introduced into ZIF-8 or other MOF frameworks before pyrolysis at 900-1000°C, facilitating the formation of adjacent metal sites through nitrogen bridging [23] [30].

Structural Characterization: Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) provides direct visualization of individual metal atoms, with contrast analysis confirming atomic dispersion through Z-contrast differences [29]. X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) analysis at synchrotron facilities determines the precise coordination environment and oxidation states, distinguishing between single-atom and multi-atom configurations through fitting of Fourier-transformed spectra [29]. In situ Raman and XAFS techniques track dynamic structural changes under operational conditions, such as the reconstruction from CuN₄ to CuN₁O₂ coordination in self-healing catalysts [29].

Electrochemical Validation: Standard three-electrode cells with rotating disk electrodes (RDE) or rotating ring-disk electrodes (RRDE) evaluate ORR/OER activity in 0.1 M KOH or 0.1 M HClO₄ electrolytes. Key metrics include half-wave potentials (E₁/₂), kinetic current densities (Jₖ), and electron transfer numbers. For CO₂ reduction, H-type cells or flow cells quantify product distribution via gas chromatography and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, reporting Faradaic efficiencies at various current densities and overpotentials [29] [27]. Long-term stability tests assess performance retention over extended operation (typically 10-100 hours), with post-test characterization confirming structural integrity.

Structural and Catalytic Relationships Visualization

This structural diagram illustrates the evolutionary pathway from single-atom to multi-atom catalysts and their corresponding performance characteristics. The relationships show how increasing structural complexity enables more sophisticated catalytic control through synergistic effects and multi-site cooperativity, ultimately translating to enhanced performance across various applications.

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Atomic-Scale Catalyst Development

| Category | Specific Materials/Reagents | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Metal phthalocyanines, Metalloporphyrins, Metal acetylacetonates, Metal nitrates | Provide metal sources for atomic dispersion | Choice affects metal loading and distribution; heteronuclear DACs/TACs require controlled stoichiometry |

| Support Materials | ZIF-8, PCN-222, Graphene oxide, Carbon black, MOF derivatives | Create anchoring sites for metal atoms | High surface area (>1000 m²/g) and N-content crucial for stabilization |

| Doping Agents | Melamine, Dicyandiamide, Ammonia gas, Thiourea | Introduce heteroatoms (N, S, P) into carbon matrix | Enhance metal-support interaction; tune electronic structure |

| Characterization Standards | Ni mesh grids for TEM, Pt wire counter electrodes, Ag/AgCl reference electrodes | Enable accurate structural and electrochemical analysis | Standardized protocols essential for cross-study comparisons |

| Computational Resources | VASP software, GPAW, Quantum ESPRESSO, Materials Project databases | DFT calculations and ML-guided screening | Required for predicting stability and activity before synthesis |

| Electrochemical Reagents | 0.1 M KOH, 0.1 M HClO₄, Nafion binder, Isopropanol | Catalyst ink preparation and performance testing | Electrolyte purity critical for reproducible measurements |

The systematic comparison of single-atom, diatomic, and triatomic catalysts reveals a clear trajectory in catalyst development toward increasingly sophisticated multi-atom architectures with enhanced capabilities for complex reactions. SACs provide exceptional performance for single-step reactions with maximal atom utilization, DACs introduce valuable synergistic effects for optimized intermediate adsorption, while TACs enable sophisticated spin state regulation and multi-site cooperativity for the most challenging multi-electron processes.

Selection of the appropriate catalyst class depends fundamentally on the specific reaction requirements. SACs remain ideal for simple transformations where cost efficiency and selectivity are paramount. DACs offer superior performance for reactions requiring optimized adsorption of multiple intermediates, particularly in energy conversion applications like ORR/OER. TACs demonstrate exceptional capabilities for complex multi-electron reactions and challenging operating conditions, including low-temperature energy conversion and sophisticated biomedical applications.

For experimental validation research, the integration of computational screening with precise synthesis and thorough characterization provides the most robust approach for developing next-generation atomic-scale catalysts. The continued refinement of machine learning and natural language processing methods will further accelerate the discovery and optimization of these materials, ultimately enabling their translation from laboratory research to practical applications across energy, environmental, and biomedical domains.

The development and optimization of modern catalysts, particularly heterogeneous catalysts, rely heavily on advanced characterization techniques to elucidate their structural and chemical properties. Among the most critical tools in the researcher's arsenal are X-ray fluorescence (XRF), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and X-ray diffraction (XRD). These X-ray-based analytical methods provide complementary information spanning from bulk composition to surface chemistry and crystalline structure, enabling comprehensive catalyst analysis. Within the context of standard catalyst materials for experimental validation research, understanding the distinct capabilities, applications, and limitations of each technique is fundamental to designing effective characterization protocols and interpreting experimental data accurately. This guide provides a systematic comparison of XRF, XPS, and XRD, detailing their underlying principles, specific applications in catalyst research, experimental methodologies, and data interpretation frameworks to support researchers in selecting the most appropriate technique for their specific investigative needs.

The table below provides a high-level comparison of the three X-ray techniques, highlighting their primary functions, analytical depths, and key applications in catalyst research.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of XRF, XPS, and XRD

| Feature | XRF (X-ray Fluorescence) | XPS (X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy) | XRD (X-ray Diffraction) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Elemental composition (qualitative & quantitative) | Elemental & chemical state analysis of surfaces | Phase identification, crystal structure determination |

| Information Depth | Bulk (µm to mm) [32] | Ultra-surface (1-10 nm) [33] | Bulk (µm scale) [34] |

| Key Catalyst Applications | Analyzing Pt, Pd, Rh in catalytic converters; Si/Al ratios in zeolites; detecting catalyst poisons (Cl, S) [34] | Studying active sites, reaction mechanisms, and deactivation processes; determining metal oxidation states and dispersion [34] [33] [35] | Identifying crystalline phases (e.g., metal oxides, zeolites); determining crystal size and unit cell parameters [34] |

| Sample Requirements | Solids, liquids, powders; minimal preparation [32] | Solid, vacuum-compatible samples | Solid, crystalline materials |

| Destructive? | No | No | No |

| Quantitative Capability | Yes, with standards [32] | Yes, semi-quantitative | Yes (e.g., Rietveld refinement) |

Principle of Operation and Data Output

Each technique operates on distinct physical principles, yielding different types of data crucial for catalyst characterization.

X-ray Fluorescence (XRF)

- Principle: When a material is irradiated with high-energy X-rays, core-shell electrons are ejected. The subsequent relaxation process, where outer-shell electrons fill the inner-shell vacancies, results in the emission of secondary (fluorescent) X-rays. The energy of these emitted X-rays is characteristic of the atomic elements present, allowing for qualitative analysis, while the intensity correlates with concentration for quantitative analysis [32].

- Data Output: An XRF spectrum displays the intensity of emitted X-rays as a function of their energy. Each element presents a unique spectral signature, enabling identification and quantification. For example, in fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) catalysts, XRF can precisely measure concentrations of Al, Ni, V, and S [34].

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

- Principle: Based on the photoelectric effect, XPS uses soft X-rays to irradiate a sample, causing the emission of photoelectrons from core levels. The kinetic energy of these emitted electrons is measured, and their binding energy is calculated using Einstein's law: Ek = hν - Eb, where Ek is kinetic energy, hν is the incident X-ray energy, and Eb is the electron binding energy [33]. The binding energy is element-specific and sensitive to the chemical environment, providing information on chemical states.

- Data Output: A wide-scan spectrum identifies elements present on the surface. High-resolution scans of individual element peaks reveal chemical shifts. For instance, the binding energy of Pd 3d electrons shifts depending on whether the palladium is in a metallic or oxidized state in a pumice-supported catalyst [33].

X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

- Principle: XRD relies on the constructive interference of a monochromatic X-ray beam scattered by the periodic lattice of atoms in a crystalline material. Bragg's Law, nλ = 2d sinθ, describes the condition for diffraction, where n is an integer, λ is the X-ray wavelength, d is the interplanar spacing, and θ is the diffraction angle. The resulting pattern is a fingerprint of the crystal structure [36].

- Data Output: A diffractogram plots X-ray intensity as a function of the diffraction angle 2θ. The positions of the peaks identify the crystalline phases present, while peak broadening can be used to determine crystallite size via the Scherrer equation [34].

Experimental Protocols for Catalyst Characterization

The following section outlines standard operational procedures for each technique in the context of catalyst analysis.

XRF Analysis Protocol

- Sample Preparation: For solid catalysts, powders are often ground to a fine, homogeneous consistency and pressed into a pellet. Liquid samples may require a specialized cell [32].

- Calibration: The instrument is calibrated using certified reference materials (CRMs) with a matrix similar to the catalyst being analyzed to ensure quantitative accuracy [32].

- Measurement: The sample is irradiated, and the fluorescent X-rays are detected. Wavelength-dispersive XRF (WDXRF) uses an analytical crystal to diffract specific wavelengths for high-resolution analysis, while energy-dispersive XRF (EDXRF) collects a broad spectrum simultaneously with a solid-state detector [34] [32].

- Data Analysis: Spectral peaks are identified and matched to elements. Concentrations are calculated based on calibration curves.

XPS Analysis Protocol

- Sample Preparation: Catalyst powder is typically mounted on a stub using conductive tape or as a thin film. The sample must be compatible with ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions (typically < 10⁻⁸ mbar) [33].

- Charge Neutralization: For insulating catalyst supports (e.g., alumina, silica), a low-energy electron flood gun is used to neutralize positive surface charge buildup.

- Energy Calibration: The spectrometer's energy scale is calibrated using known peaks, such as Au 4f₇/₂ at 84.0 eV or C 1s from adventitious carbon at 284.8 eV.

- Data Acquisition: A survey scan is first acquired to identify all elements. High-resolution regional scans are then collected for elements of interest (e.g., the active metal and key support elements).

- Data Analysis: Peaks are fitted with synthetic components to quantify species in different chemical states. The Auger parameter (α) can provide additional chemical state information [33].

XRD Analysis Protocol

- Sample Preparation: Catalyst powder is loaded into a sample holder, and the surface is smoothed to ensure a flat, random orientation of crystallites.

- Instrument Alignment: The X-ray source and detector are aligned according to the manufacturer's specifications.

- Data Collection: The sample is rotated (θ) while the detector moves through a range of 2θ angles, typically from 5° to 80° or 90°, counting the diffracted X-ray photons at each step.

- Phase Identification: The resulting diffractogram is compared to a database of reference patterns, such as the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) PDF database.

- Advanced Analysis: For more detailed structural analysis, Rietveld refinement is performed to extract precise lattice parameters, phase fractions, and crystallite size [34]. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) can be used to analyze particle size and porosity [34].

Advanced Applications and Emerging Trends

The application of these techniques is rapidly evolving, particularly with the integration of in-situ/operando methods and artificial intelligence.

In-situ and Operando Studies

A significant trend in catalyst characterization is moving beyond ex-situ analysis to study catalysts under realistic reaction conditions. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), often performed at synchrotron facilities, allows researchers to follow reactions in-situ and in-operando, providing dynamic information about the local structure and electronic properties of a specific element, both on the surface and in the bulk, without affecting the catalyst state [34]. This is crucial for understanding active sites and reaction mechanisms during operation.

The Role of AI and Machine Learning

Machine learning is revolutionizing data analysis and interpretation. DiffractGPT is a generative pre-trained transformer model designed to predict atomic structures directly from XRD patterns, significantly accelerating the inverse design process in materials discovery [36]. This approach captures intricate relationships between diffraction patterns and crystal structures, reducing reliance on iterative fitting and expert intervention.

Complementary Technique: X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS)

While not the focus of this guide, XAS is a powerful complementary technique, especially available at synchrotron facilities. It provides detailed information about the local coordination environment and oxidation state of a specific element within a catalyst. Unlike XPS, it is not limited to the surface and can probe the bulk structure, making it ideal for studying reactions within porous catalyst materials [34].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The table below lists key materials, standards, and software tools essential for conducting reliable XRF, XPS, and XRD analyses in catalyst research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for X-ray Characterization

| Category | Specific Item / Standard | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) for XRF/XPS | Calibrating instruments for quantitative elemental analysis [32]. |

| NIST Standard Reference Materials (e.g., for XRD) | Verifying instrument alignment and data quality in XRD. | |

| Sample Preparation | Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) or Boric Acid | Binder for powder pelleting in XRF analysis. |

| Conductive Tape/Carbon Tape | Mounting powder samples for XPS analysis. | |

| Software Tools | GSAS, FullProf, TOPAS | Performing Rietveld refinement on XRD data [36]. |

| CasaXPS, Avantage | Processing and quantifying XPS spectral data. | |

| Specialized Equipment | Hydraulic Pellet Press | Preparing uniform powder pellets for XRF and XRD. |

| UHV Introduction Chamber | Safe sample transfer into XPS analysis chamber without breaking vacuum. |

Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting the appropriate characterization technique based on the specific information required for catalyst analysis.

XRF, XPS, and XRD are cornerstone techniques in the fundamental characterization of catalyst materials, each providing unique and critical insights. XRF excels in bulk elemental analysis, XPS offers unparalleled surface sensitivity and chemical state information, and XRD is the definitive tool for identifying crystalline phases and structural properties. The global market for XRD and XRF instruments is a testament to their importance, projected to grow significantly, driven by demand from material science, chemistry, and pharmaceuticals [37]. For a comprehensive understanding of a catalyst, these techniques are often used in concert, as their strengths are highly complementary. The ongoing integration of in-situ capabilities and artificial intelligence promises to further enhance their power, enabling faster, more dynamic, and more profound insights into the structure-function relationships that govern catalytic performance. This, in turn, accelerates the rational design and experimental validation of next-generation catalyst materials.

Synthesis and Characterization Methods for Catalyst Development and Application

The development of high-performance catalysts is pivotal for advancing renewable energy systems, environmental protection, and sustainable chemical processes. Traditional catalyst development has long relied on resource-intensive empirical methods, but recent technological advances are revolutionizing this field. Modern synthesis strategies now leverage precise pyrolysis control and sophisticated post-treatment techniques to tailor catalyst properties at the nanoscale, enabling unprecedented control over activity, selectivity, and stability. These approaches are particularly critical for overcoming fundamental challenges in catalyst design, such as the reactivity-stability trade-off that often limits practical application.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of advanced catalyst synthesis methodologies, with particular emphasis on pyrolysis control and post-treatment strategies. We present systematically organized experimental data and detailed protocols to facilitate informed decision-making for researchers developing catalyst materials for experimental validation. The integration of automation and artificial intelligence in catalyst design represents a paradigm shift in the field, enabling accelerated discovery and optimization of next-generation catalytic materials for diverse applications from energy storage to water treatment.

Pyrolysis Control Strategies for Catalyst Synthesis

Flame Spray Pyrolysis (FSP) Systems

Flame Spray Pyrolysis (FSP) has emerged as a versatile synthetic approach for producing inorganic mixed-metal nanoparticles with well-defined compositions and tunable physical properties. This technique is particularly valuable for creating catalysts, battery materials, and chromophores. The FSP process involves multiple physical steps: precursor evaporation, oxidation, nucleation, and subsequent solid particle growth mechanisms, resulting in highly characteristic particle architectures that often differ considerably from materials of the same nominal composition produced via wet chemistry methods [38].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Pyrolysis Techniques for Catalyst Synthesis

| Synthesis Method | Compositional Accuracy | Specific Surface Area Range | Scalability | Typical Applications | Automation Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flame Spray Pyrolysis (FSP) | ±5% relative error [38] | 60-200 m²/g [38] | Excellent scale-up; continuous operation possible [38] | Mixed metal oxide catalysts, battery materials [38] | High (AutoFSP demonstrated) [38] |

| Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis | Varies with catalyst type | Varies significantly with catalyst | Moderate; depends on reactor design | Bio-oil production, waste conversion [39] | Moderate |

| Conventional Co-precipitation | Moderate (±10-15%) | Lower, susceptible to sintering | Well-established batch processes | Basic catalyst supports | Low |

A significant advancement in FSP technology is the development of automated robotic platforms. The novel AutoFSP system demonstrates remarkable performance in accelerating materials discovery while providing standardized, machine-readable documentation of all synthesis steps. This automated platform reduces operator workload by a factor of two to three while improving documentation and decreasing the chance of human experimental error. In terms of compositional accuracy, AutoFSP achieves precision across two orders of magnitude, with relative error of effective molar metal loading in ZnₓZr₁₋ₓOᵧ and InₓZr₁₋ₓOᵧ nanoparticles remaining within ±5% [38]. The resulting nanopowders typically possess high specific surface areas (60-200 m²/g) and demonstrate remarkable resistance to sintering even at elevated temperatures (e.g., 600°C), where materials prepared by comparable low-temperature methods would readily experience reduction of specific surface areas [38].

Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis (CFP) of Biomass

Catalytic fast pyrolysis represents another significant application of pyrolysis control, particularly for biomass conversion to valuable fuels and chemicals. This approach introduces catalysts to pyrolysis processes to promote dehydration, decarboxylation, and decarbonylation reactions, consequently improving bio-oil quality. When biomass is co-processed with hydrogen-rich feedstocks, significant synergistic effects can be achieved, enhancing oil quality through hydrogen transfer in a single reactor [39].

The effectiveness of catalytic pyrolysis systems heavily depends on catalyst selection. ZSM-5 zeolite is the most frequently employed catalyst, featured in more than 55% of studies due to its shape selectivity toward aromatics. Zeolite Y represents the second most popular choice (10% of studies), valued for its large pore system. Among mesoporous silica catalysts, MCM-41 and SBA-15 each attract approximately 7% of research focus [39]. The choice of hydrogen-rich co-feed significantly influences process outcomes, with plastics dominating research (69% of studies) due to their abundance in waste streams, while alcohols also gain attention for their high effective hydrogen index and favorable reaction mechanisms [39].

Experimental Protocol: Automated FSP Synthesis

Materials and Equipment:

- Metal precursor solutions: 2-ethylhexanoic acid (2-EHA) salts of target metals (e.g., Zr(IV) 2-ethylhexanoate, Zn(II) 2-ethylhexanoate)

- Solvent system: 2:1 (w/w) mixture of 2-ethylhexanoic acid and tetrahydrofuran (THF)

- AutoFSP system with programmable logic controller (PLC)

- FSP nozzle assembly with annular CH₄/O₂ flame

- Water-cooled reactor with high-temperature glass fiber filter

- Gas flow control system

Procedure:

- Prepare precursor solutions by diluting commercial 2-ethylhexanoate metal salts to target concentrations (typically 400-500 mmol/kg for major components) [38].

- Program the AutoFSP system with desired synthesis parameters via the human-machine interface (HMI).

- Set flame conditions: Adjust O₂-to-fuel ratio to control particle residence time and size distribution [38].

- Initiate automated synthesis sequence: The system precisely meters precursor mixtures into the dispersion nozzle.

- Monitor process parameters through the PLC interface, including flame stability, gas flows, and reactor temperature.

- Collect synthesized nanoparticles on the high-temperature filter assembly.

- Document all process parameters automatically in machine-readable format for reproducibility.

Key Parameters for Optimization:

- Precursor composition and concentration

- O₂-to-fuel ratio in the annular flame

- Solvent mixture composition

- Dispersion gas flow rate

- Filter temperature and collection time

Post-Treatment Approaches for Catalyst Enhancement

Spatial Confinement Strategies

Post-synthesis treatment plays a critical role in enhancing catalyst stability and maintaining reactivity under operational conditions. A particularly innovative approach involves spatial confinement at the angstrom scale to significantly enhance catalyst stability. Research has demonstrated that confining iron oxyfluoride (FeOF) catalysts between layers of graphene oxide can dramatically improve longevity while preserving catalytic activity. In flow-through operations, such catalytic membranes maintain near-complete removal of model pollutants (neonicotinoids) for over two weeks by effectively activating H₂O₂ to generate •OH radicals [40].

The spatial confinement approach addresses a fundamental challenge in catalyst design: the reactivity-stability trade-off. Conventional iron oxyhalide catalysts, while initially highly efficient, suffer from significant deactivation during operation due to halide leaching. Studies show that FeOF loses approximately 40.2 at.% fluorine and 33.0 at.% iron during H₂O₂ activation, with FeOCl experiencing even more pronounced leaching (76.1 at.% chlorine and 43.2 at.% iron) [40]. Spatial confinement mitigates this deactivation by physically restricting the movement of leached ions, thereby preserving catalytic active sites.

Table 2: Post-Treatment Methods for Catalyst Performance Enhancement

| Post-Treatment Method | Key Mechanism | Performance Improvement | Limitations | Best Suited Catalyst Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Confinement in 2D Materials | Physical restriction of ion leaching and particle growth | Near-complete pollutant removal maintained for >2 weeks [40] | Complex fabrication process | Iron oxyhalides, single-atom catalysts |

| Hierarchical Zeolite Design (AI-optimized) | Controlled desilication/dealumination creates mesoporosity | BET surface area prediction accuracy R²=0.8765 [41] | Requires precise control of synthesis conditions | Zeolite catalysts (SAPO-34, ZSM-5) |

| Catalyst Reconstruction | In-situ transformation under reaction conditions | Enhanced oxygen evolution reaction performance [42] | Difficult to predict and control reconstruction process | Metal oxides for electrocatalysis |

AI-Guided Catalyst Optimization

Artificial intelligence has revolutionized post-synthesis catalyst optimization by enabling predictive design of hierarchical structures. Machine learning models, including artificial neural networks (ANN) and random forest (RF) algorithms, can accurately predict key catalyst properties such as BET surface area, micropore area, external surface area, and average particle size based on synthesis parameters [41]. For SAPO-34 catalysts, sensitivity analysis has revealed the most influential synthesis parameters: crystallization time for BET surface area, Al₂O₃ content for micropore surface area, precursor sequence addition for external surface area, and TEAOH concentration for particle size [41].

The predictive accuracy of these AI models is remarkable, with RF models achieving R² values of 0.8765, 0.8894, and 0.9698 for BET, micropore, and external surface areas, respectively. ANN models demonstrate even higher precision for particle size prediction, with an R² of 0.9950. Experimental verification confirms minimal errors, with predictions of BET and micropore surface areas deviating by just 3% and 4% from experimental values [41].

Experimental Protocol: Spatial Confinement for Enhanced Stability

Materials:

- Iron oxyfluoride (FeOF) catalyst powder

- Graphene oxide suspension

- Target pollutants (e.g., neonicotinoids)

- Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) solution

- Filtration apparatus

- Standard analytical equipment (HPLC, UV-Vis)

Procedure:

- Synthesize FeOF catalyst by heating FeF₃·3H₂O in methanol medium at 220°C for 24 h in an autoclave [40].

- Prepare graphene oxide suspension using modified Hummers' method.

- Fabricate composite membrane by intercalating FeOF between graphene oxide layers through vacuum filtration.

- Characterize fresh and spent catalysts using XRD, XPS, SEM, and TEM to confirm structure and evaluate degradation.

- Evaluate catalytic performance in flow-through reactor system with model pollutants (e.g., thiamethoxam).

- Monitor radical generation efficiency using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy with DMPO as spin trapping agent.

- Quantify element leaching through ICP-OES for iron and ion chromatography for fluoride at regular intervals.

Analytical Methods:

- Catalyst characterization: XRD, XPS, SEM, TEM

- Performance evaluation: Pollutant removal efficiency, H₂O₂ consumption rate

- Stability assessment: Elemental leaching analysis, long-term continuous operation

- Radical quantification: EPR spectroscopy with DMPO spin trapping

Integrated Workflows and Research Tools

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Advanced Catalyst Synthesis and Evaluation

| Reagent/Category | Function in Catalyst Development | Example Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal 2-ethylhexanoates | Precursors for FSP synthesis | Mixed metal oxide nanoparticles [38] | Good miscibility, air stability, commercial availability |

| ZSM-5 Zeolite | Acid catalyst for shape-selective reactions | Catalytic fast pyrolysis, biomass conversion [39] | Si/Al ratio, particle size, and mesoporosity affect performance |

| Graphene Oxide | 2D confinement matrix for catalyst stabilization | Iron oxyhalide membranes for water treatment [40] | Layer number, oxygen content, and dispersion quality |

| DMPO (5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide) | Spin trapping agent for radical detection | Quantifying •OH generation in AOPs [40] | Short half-life requires fresh preparation |

| SAPO-34 | Molecular sieve for acid-catalyzed reactions | Methanol-to-olefins conversion [41] | Template choice dramatically affects porosity |

| H₂O₂ | Oxidant for advanced oxidation processes | Catalyst evaluation in water treatment [40] | Concentration and addition rate affect radical generation |

AI-Driven Catalyst Discovery Framework

Modern catalyst development increasingly leverages artificial intelligence to accelerate discovery and optimization. The CatDRX framework represents a significant advancement in this area, employing a reaction-conditioned variational autoencoder generative model for designing catalysts and predicting catalytic performance. This approach integrates structural representations of catalysts with associated reaction components to capture their relationship to reaction outcomes [43].

The framework operates through three main modules: (1) catalyst embedding module that processes catalyst structural information, (2) condition embedding module that learns other reaction components (reactants, reagents, products, reaction time), and (3) autoencoder module that maps inputs into a latent space for catalyst generation and property prediction [43]. This architecture enables inverse design of catalysts tailored to specific reaction conditions, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches.

AI-Integrated Catalyst Development Workflow

Market Outlook and Future Directions

The global market for high-performance catalysts is projected to experience steady growth, expanding at a CAGR of 4.7% from 2025 to 2035, reaching USD 6,707.3 million by 2035 [2]. This growth is driven by increasing demand for cleaner energy solutions and advanced refining technologies, with a notable shift toward renewable feedstocks in oil refining. The chemical synthesis catalyst market specifically was valued at USD 10.6 billion in 2025 and is projected to grow at a CAGR of 4.5% during the forecast period [44].

Regionally, Asia-Pacific dominates the chemical synthesis catalyst market, accounting for over 50% of global demand, with China alone representing over 30% of regional demand [44]. The petrochemical industry remains the largest consumer of chemical synthesis catalysts, while environmental applications represent the fastest-growing segment [2].

Future catalyst development will increasingly focus on multifunctional materials capable of operating under harsh conditions while maintaining selectivity. Key emerging trends include:

- Self-healing and self-regenerating catalyst systems [44]

- Machine learning-assisted catalyst design and optimization [41] [43]

- Integration of catalyst systems with process automation [38]

- Development of catalysts for specialty and high-value applications [2]

Interrelationship Between Synthesis Methods and Catalyst Properties

The strategic integration of controlled pyrolysis techniques and advanced post-treatment methods represents a powerful approach for developing next-generation catalysts with tailored properties. Flame spray pyrolysis offers exceptional compositional control and scalability for mixed metal oxide catalysts, while catalytic fast pyrolysis enables efficient conversion of biomass and waste materials into valuable products. Post-synthesis treatments, particularly spatial confinement strategies and AI-guided optimization, address fundamental challenges in catalyst stability without compromising reactivity.

The experimental protocols and comparative data presented in this guide provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these advanced synthesis strategies. As the field evolves, the convergence of automated synthesis platforms, AI-driven design, and sophisticated characterization techniques will further accelerate the development of high-performance catalysts for sustainable energy and environmental applications. Researchers are encouraged to adopt integrated workflows that combine computational prediction with experimental validation to maximize efficiency in catalyst development pipelines.