AI-Driven Predictive Modeling for Catalyst Activity and Selectivity: Accelerating Discovery in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are revolutionizing the prediction of catalyst activity and selectivity, crucial for sustainable drug development and...

AI-Driven Predictive Modeling for Catalyst Activity and Selectivity: Accelerating Discovery in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are revolutionizing the prediction of catalyst activity and selectivity, crucial for sustainable drug development and chemical synthesis. We explore the foundational shift from trial-and-error methods to data-driven discovery, detailing key techniques from high-throughput virtual screening to inverse design. For researchers and drug development professionals, the content covers practical methodologies, addresses common challenges like model overfitting and validation, and presents a framework for robust performance assessment. By synthesizing the latest advances and validation strategies, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to effectively implement predictive modeling, thereby accelerating the development of efficient and selective catalysts for biomedical applications.

From Trial-and-Error to AI: The New Paradigm in Catalyst Discovery

The Limitations of Traditional Catalyst Development and the Case for AI

Catalysts are fundamental to modern industry, accelerating chemical reactions and enhancing product selectivity in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to energy production. It is estimated that over 90% of industrial chemical processes utilize catalysts at some stage [1]. Traditionally, the discovery and optimization of these catalysts have relied on a trial-and-error approach, a process that is not only time-consuming and resource-intensive but also inherently limited in its ability to navigate the vast, high-dimensional search space of possible materials [2] [1].

The contemporary urgency for more sustainable and efficient industrial processes has exacerbated the limitations of these conventional methods. This document details the specific constraints of traditional catalyst development and makes the case for Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) as transformative technologies. Framed within the context of predictive modeling for catalyst activity and selectivity research, we present quantitative comparisons, detailed AI-driven protocols, and visualizations of the new paradigm that is sharply transforming the research landscape [2].

Quantitative Limitations of Traditional Workflows

The traditional catalyst development cycle is a multi-step process that can take several years from initial screening to industrial application [3]. Its inefficiencies can be quantified across several key dimensions, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Limitations of Traditional Catalyst Development

| Limitation Dimension | Traditional Approach Characteristics | Impact on Research & Development |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal & Resource Cost | Development cycles spanning years; manual, sequential experimentation [3] [1]. | High consumption of manpower and material costs; lengthy research cycles introduce uncertainty [2]. |

| Search Space Navigation | Relies on empirical knowledge and intuition; struggles with complex parameter interplay [1]. | Inability to efficiently explore vast combinatorial spaces of composition, structure, and synthesis conditions [2] [3]. |

| Data Handling & Utilization | Data often lack standardization; analysis is slow and may miss complex, non-linear patterns [2]. | Prevents comprehensive data-driven insight; limits the ability to establish robust structure-activity relationships [2]. |

| Deactivation & Longevity Analysis | Study of deactivation pathways (e.g., coking, poisoning) is reactive and slow [4]. | Compromises catalyst performance, efficiency, and sustainability; costly unplanned downtime in industrial processes [4]. |

The core scientific challenge lies in the complexity and high dimensionality of the search space, which includes catalyst composition, structure, reactants, and synthesis conditions. This makes it nearly impossible to find optimal catalysts through manual methods alone [2] [1].

The AI-Driven Paradigm: A Strategic Framework

AI, particularly machine learning, offers a paradigm shift by leveraging data to build predictive models and accelerate discovery. These models can effortlessly uncover underlying patterns and features from large and complex experimental and computational datasets, facilitating the prediction of composition, structure, and performance of unknown catalysts [2].

AI Methodologies in Catalyst Design

Several AI techniques are being deployed to address specific challenges in catalyst development:

- Supervised Learning for Predictive Modeling: ML regression models and neural networks are trained on existing data to predict catalytic properties such as activity, selectivity, and stability based on molecular descriptors or structural features [2] [1]. This allows for virtual screening of millions of candidates, drastically narrowing the field to the most promising ones for experimental validation.

- Generative Models for Inverse Design: Moving beyond prediction, models like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and generative adversarial networks can design novel catalyst candidates from scratch. Frameworks like CatDRX use a reaction-conditioned VAE to generate potential catalyst structures tailored to specific reaction environments and desired outcomes [3].

- Autonomous Discovery Systems: The integration of AI with robotic automation creates closed-loop, "self-driving" labs. Systems like the CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists) platform can converse with researchers in natural language, use multimodal data (literature, experimental results, images) to plan experiments, and employ robotic equipment to synthesize, characterize, and test materials, with results fed back to the AI to refine its future suggestions [5].

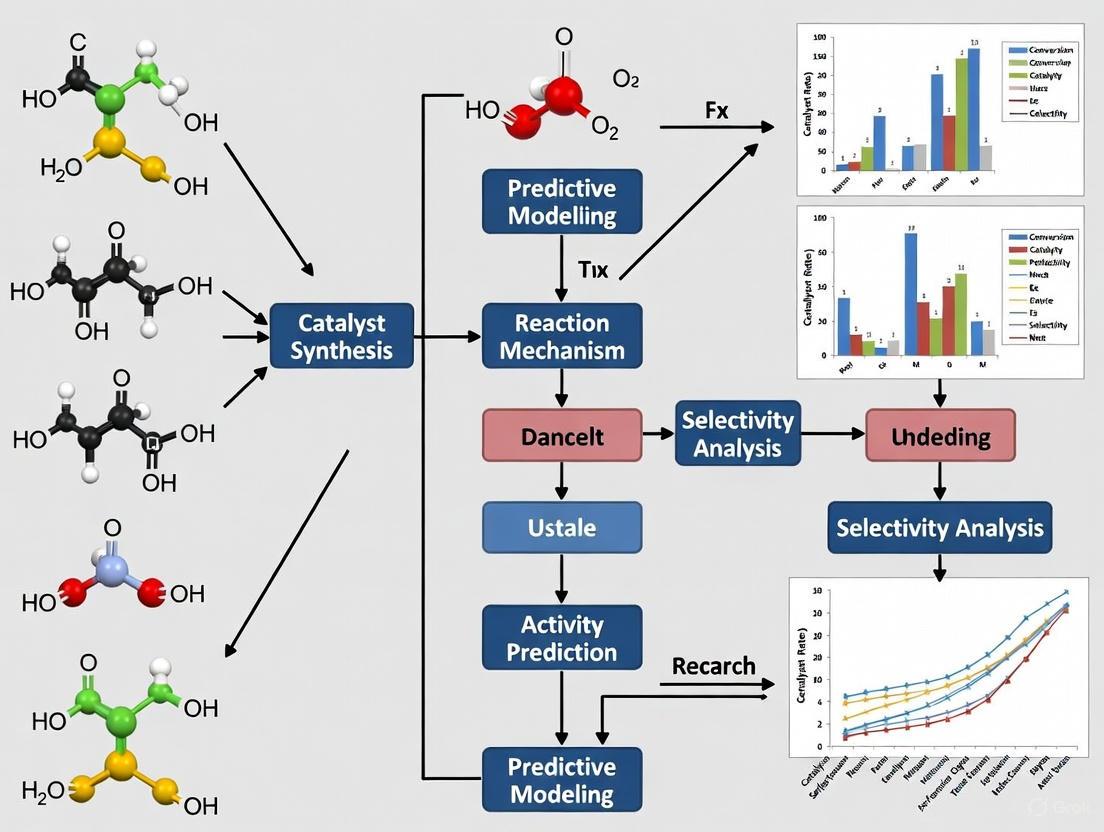

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of an AI-driven autonomous discovery system.

AI-Driven Catalyst Discovery Workflow

Application Note: AI for a Direct Formate Fuel Cell Catalyst

Background and Objective

The development of high-density fuel cells is plagued by the reliance on expensive precious metals like palladium and platinum. The objective of this application was to use an AI-driven autonomous system to discover a multielement catalyst that significantly reduces precious metal content while achieving record power density in a direct formate fuel cell [5].

Experimental Protocol

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Solutions | Source of catalytic elements (e.g., Pd, Fe, Co, Ni, etc.) | Up to 20 precursors can be included in the recipe [5]. |

| Palladium Salts | Primary precious metal component for baseline activity. | AI goal was to reduce Pd content while maintaining performance. |

| Formate Salt | Fuel source for the direct formate fuel cell performance testing. | Critical for evaluating the catalytic activity in the target application. |

| Automated Electrochemical Workstation | For high-throughput testing of catalyst performance. | Measures key metrics like power density and catalytic activity [5]. |

Protocol Steps:

- Goal Definition: Researchers communicated the objective—"discover a low-cost, high-power-density fuel cell catalyst"—to the CRESt platform via natural language [5].

- AI-Driven Experiment Planning: The AI used a combination of Bayesian optimization and knowledge mined from scientific literature to design new catalyst recipes. It worked not in the full element space but in a reduced knowledge embedding space to increase efficiency [5].

- Robotic Synthesis: A liquid-handling robot and a carbothermal shock system were used to synthesize the catalyst candidates designed by the AI, ensuring rapid and reproducible preparation [5].

- Automated Characterization & Testing: The synthesized materials were automatically characterized (e.g., via electron microscopy) and their electrochemical performance was evaluated in a fuel cell setup using the automated electrochemical workstation [5].

- Multimodal Feedback and Model Update: Results from characterization and testing, along with literature knowledge and human feedback, were fed into the AI's models to augment its knowledge base and redefine the search space for the next iteration [5].

- Iterative Optimization: Steps 2-5 were repeated autonomously over multiple cycles. The system conducted 3,500 electrochemical tests across 900 different chemistries over three months [5].

Results and Validation

The AI discovered a catalyst composed of eight elements that achieved a 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar compared to pure palladium. This catalyst set a record power density for a working direct formate fuel cell while containing only one-fourth the precious metals of previous state-of-the-art devices [5]. The catalyst's structure and performance were validated using computational chemistry tools and extensive lab testing, confirming the AI's prediction.

Protocol: Implementing a Generative Model for Catalyst Design

This protocol outlines the procedure for using a generative AI model, such as the CatDRX framework, for the inverse design of novel catalyst candidates [3].

Model Pre-training

- Data Collection: Gather a broad, diverse dataset of chemical reactions and associated catalysts. The Open Reaction Database (ORD) is a suitable source [3].

- Model Architecture Setup: Implement a Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) architecture. This should include:

- A catalyst embedding module (e.g., using graph neural networks for molecular structure).

- A condition embedding module to process other reaction components (reactants, products, solvents, temperature).

- A predictor module to estimate catalytic performance (e.g., yield) [3].

- Pre-training: Train the entire model on the broad dataset to learn fundamental relationships between catalyst structures, reaction conditions, and outcomes.

Downstream Fine-Tuning

- Target Dataset Curation: Compile a smaller, specialized dataset for the specific catalytic reaction of interest (e.g., asymmetric synthesis, cross-coupling).

- Transfer Learning: Fine-tune the pre-trained model on this target dataset. This allows the model to adapt its general knowledge to the specific domain, improving prediction accuracy and generation relevance [3].

Inverse Design and Validation

- Condition Input: Define the target reaction conditions, including reactants, desired products, and any constraints.

- Candidate Generation: Use the fine-tuned model's decoder to generate novel catalyst structures conditioned on the target reaction and optimized for high predicted performance.

- Knowledge Filtering: Pass the generated catalysts through filters based on chemical knowledge (e.g., synthesizability, stability, absence of toxic functional groups) [3].

- Computational Validation: Employ Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations to validate the predicted activity and reaction mechanisms of the top candidate molecules before proceeding to lab synthesis [3].

The logical flow of this generative design process is captured in the diagram below.

Generative AI Catalyst Design Process

The limitations of traditional catalyst development—prohibitive cost, extensive timelines, and an inability to navigate complex search spaces—are no longer tenable in the face of modern scientific and environmental challenges. AI provides a compelling case for a new approach. Through predictive modeling, AI accelerates the screening process; through generative design, it invents novel candidates beyond human intuition; and through autonomous discovery, it creates a closed-loop system that continuously learns and improves.

The showcased application note and protocols demonstrate that AI is not a distant promise but a present-day tool delivering tangible breakthroughs, such as catalysts that dramatically reduce cost and improve performance. For researchers in catalysis and drug development, the integration of AI into their workflows is becoming imperative to drive innovation, enhance sustainability, and maintain a competitive edge. The future of catalyst discovery lies in the powerful collaboration between human expertise and digital intelligence.

Predictive modeling in catalysis represents a paradigm shift from traditional, trial-and-error experimentation to a data-driven discipline. It uses machine learning (ML) and computational models to forecast a catalyst's key performance metrics—activity (the rate of the reaction), selectivity (the ability to produce a desired product), and stability—before physical experiments are conducted [6] [7]. This approach is foundational for the rational design of catalysts, significantly accelerating the discovery and optimization of materials for applications ranging from sustainable energy to chemical synthesis [8].

Core Principles and Quantitative Descriptors

The predictive capability of these models hinges on identifying and utilizing descriptors—quantifiable properties of a catalyst that correlate with its performance. These descriptors serve as a bridge between a catalyst's structure and its observed functionality.

Electronic Structure Descriptors

For heterogeneous catalysts, particularly metals and alloys, electronic structure descriptors derived from the d-band of electrons are paramount [6].

- d-band center: The average energy of the d-electron states relative to the Fermi level. A higher d-band center correlates with stronger adsorbate binding, influencing both activity and selectivity [6].

- d-band width and upper edge: Provide additional nuance, capturing subtle electronic effects that the d-band center alone may miss [6].

- d-band filling: The extent to which the d-band is occupied with electrons, identified as critical for predicting the adsorption energies of key intermediates like carbon (C), oxygen (O), and nitrogen (N) [6].

Compositional and Morphological Descriptors

Beyond electronic structure, catalyst performance is governed by:

- Elemental Composition: The identity and ratio of elements in a catalyst, such as in bimetallic or multimetallic systems, which create synergistic effects [6] [9].

- Surface Morphology and Nanoenvironment: The physical arrangement of atoms, including the presence of nanoconfining structures or polymeric additives, which can dramatically enhance selectivity, as demonstrated in CO₂ reduction to ethylene [9].

Table 1: Key Descriptors in Catalytic Predictive Modeling

| Descriptor Category | Specific Descriptor | Correlation with Catalytic Property | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure | d-band center | Adsorption energy of reaction intermediates [6] | Metal-air battery catalysts [6] |

| d-band filling | Adsorption energies of C, O, N [6] | Electrocatalyst design [6] | |

| Composition & Structure | Elemental Identity & Ratio | Activity, selectivity, and stability of multimetallic catalysts [6] [9] | CO₂ to ethylene conversion [9] |

| Nanoconfining Morphology | Product selectivity by controlling local environment [9] | High-selectivity C₂H₄ catalysts [9] | |

| Data-Driven | Engineered Features (via AFE) | Catalytic performance without prior knowledge [10] | Oxidative Coupling of Methane (OCM) [10] |

Workflow for Predictive Modeling in Catalysis

A robust predictive modeling workflow integrates data, machine learning, and validation in a cyclical process to progressively refine model understanding and catalyst design.

Diagram 1: Predictive modeling workflow for catalyst design.

Detailed Protocols for Predictive Modeling

This section outlines specific, actionable methodologies for building and applying predictive models in catalysis research.

Protocol: Building a Predictive Model Using Electronic Descriptors

This protocol is ideal for systems where established electronic descriptors, like d-band properties, are relevant [6].

1. Data Collection

- Input Features: Compile a dataset of catalyst features. For each unique catalyst in your set, calculate:

- Target Variables: Obtain experimental or high-fidelity computational data for the catalytic properties you wish to predict, such as:

2. Model Training and Validation

- Algorithm Selection: Begin with tree-based models like Random Forest (RF) or Gradient Boosting methods, which handle complex, non-linear relationships well and provide initial feature importance rankings [6].

- Validation Technique: Use k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) to ensure model generalizability and avoid overfitting. Evaluate performance using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and R² [10].

3. Interpretation and Analysis

- Feature Importance: Use SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis to quantify the contribution of each descriptor (εd, wd, fd) to the model's predictions. This identifies the primary physical drivers of catalytic performance [6].

Protocol: Automatic Feature Engineering (AFE) for Unexplored Systems

When investigating a new catalytic reaction with no established descriptors, the AFE technique allows for a hypothesis-free generation of relevant descriptors from a small dataset [10].

1. Constructing a Primary Feature Library

- For each element in a catalyst's composition, gather a wide range of general physicochemical properties (e.g., atomic radius, electronegativity, valence electron number, ionization energy) from public databases like XenonPy [10].

- Apply commutative operations (e.g., weighted average, maximum, minimum) to these properties to generate primary features that describe the multi-element catalyst as a whole, ensuring invariance to the order of elements [10].

2. Synthesis of Higher-Order Features

- Generate a vast pool of candidate descriptors (typically 10³–10⁶) by creating:

- Nonlinear features: Apply mathematical functions (e.g., log, square, exponential) to the primary features.

- Combinatorial features: Create products of two or more of these derived features to capture complex interactions [10].

3. Feature Selection and Model Building

- Selection Criterion: Use a simple, robust regression algorithm like Huber regression combined with Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV).

- Process: Iteratively test different combinations of the engineered features, selecting the set (e.g., 8 features) that minimizes the LOOCV Mean Absolute Error (MAE). This process effectively screens numerous "hypotheses" on a machine [10].

Protocol: Active Learning for Guided Catalyst Discovery

Integrate predictive modeling with high-throughput experimentation (HTE) in a closed loop to efficiently explore a vast chemical space [10].

1. Initial Model Creation

- Start with a small, initial dataset of catalyst compositions and their performance.

- Use AFE or known descriptors to build a preliminary predictive model.

2. Iterative Cycle of Learning and Experimentation

- Candidate Selection: The next set of catalysts to test is chosen based on two criteria:

- Exploration: Select catalysts that are most dissimilar to those already in the training set (using Farthest Point Sampling, FPS, in the feature space) to diversify the data.

- Exploitation: Select catalysts where the model's prediction error is highest, to improve the model in uncertain regions [10].

- HTE and Feedback: Synthesize and test the selected catalysts (e.g., 20 per cycle) via HTE. Add the new performance data to the training set.

- Model Update: Retrain the predictive model with the expanded dataset. This cycle is repeated, with each iteration refining the model's understanding and guiding the search towards high-performance catalysts [10].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Catalysis Informatics

| Category | Item / Software | Function / Application | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research Reagents & Materials | Copper-based Bimetallics | Base catalysts for CO₂ reduction to C₂H₄ products [9] | Cu heterogeneity is a key driver for selectivity [9] |

| Polymeric Additives | Modifies the catalyst's nanoenvironment to enhance C₂H₄ selectivity [9] | e.g., in CO₂RR systems [9] | |

| Supported Multi-element Catalysts | Platform for high-throughput testing and discovery [10] | e.g., for OCM reaction [10] | |

| Computational Tools | Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Calculates electronic structure descriptors (d-band center, adsorption energies) [6] | Foundational data source |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Interprets ML model predictions and determines feature importance [6] | Critical for Explainable AI (XAI) | |

| Automated Feature Engineering (AFE) | Generates and selects optimal descriptors without prior knowledge [10] | For use with small data | |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Generates novel, optimized catalyst compositions by learning data distribution [6] | For de novo catalyst design |

Application Notes and Future Perspectives

The true power of predictive modeling is realized when it is tightly coupled with experimental validation, creating a virtuous cycle that accelerates discovery.

Case Study: Electrocatalytic CO₂ Reduction to Ethylene A analysis of literature on copper-based catalysts identified key optimization trends using data-driven approaches [9]. The model's predictions highlighted that catalyst heterogeneity and the use of nanoconfining morphologies were critical descriptors for achieving high ethylene selectivity. This provides a actionable design rule that moves beyond trial-and-error. Furthermore, predictive models can differentiate between performance trends when using CO₂ versus CO as a feedstock, a crucial consideration for industrial process design [9].

The Critical Role of Explainable AI (XAI) As models become more complex, understanding their predictions is vital for gaining scientific insight, not just making forecasts. Techniques like SHAP analysis are indispensable for moving beyond "black box" models. They allow researchers to verify that a model's decision aligns with or challenges fundamental chemical principles, thereby building trust and uncovering new physical insights [6].

Future Outlook The field is advancing towards:

- Integration of Multi-Scale Data: Combining atomic-scale electronic descriptors with meso-scale morphological data and reactor-level operational conditions [7].

- Generative Design: Using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Bayesian optimization to propose entirely new catalyst compositions with desired properties, effectively inventing catalysts in silico [6].

- Enhanced Reproducibility and Standardization: Addressing the current lack of reproducibility in the field by developing robust, standardized frameworks and data reporting practices to improve the reliability and industrial relevance of predictive models [9].

Digital descriptors are quantitative measures that capture key physical, chemical, and structural properties of catalytic systems, enabling the prediction of catalyst activity, selectivity, and stability [11]. In the context of predictive modeling for catalyst research, these descriptors form the computational bridge between a catalyst's fundamental characteristics and its macroscopic performance [12]. The evolution of descriptor-based design has progressed from early energy-based descriptors to sophisticated electronic and data-driven descriptors, fundamentally transforming catalyst development from empirical trial-and-error to a rational, theory-driven discipline [11].

This paradigm shift is particularly evident in the growing application of machine learning (ML) in catalysis, where descriptors serve as critical input features for models predicting catalytic performance [13] [14] [12]. By establishing quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSARs) through appropriate descriptors, researchers can navigate vast chemical spaces efficiently, accelerating the discovery and optimization of catalytic materials for both industrial and pharmaceutical applications [15] [12].

Categories of Digital Descriptors

Active Center Descriptors

Active center descriptors quantify the properties of catalytic sites where chemical reactions occur, providing insights into adsorption strengths, reaction energy barriers, and catalytic activity trends [11].

Table 1: Major Categories of Active Center Descriptors

| Descriptor Category | Key Examples | Theoretical Foundation | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Descriptors | Adsorption energy (ΔGads), Transition state energy, Binding energy | Scaling relationships, Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) principles | Predicting catalytic activity trends via volcano plots, hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), oxygen evolution reaction (OER) [11] |

| Electronic Descriptors | d-band center, Electronegativity, Ionic potential, HOMO/LUMO energies | d-band center theory, Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Transition metal catalyst design, predicting adsorbate-catalyst bond strength [16] [11] |

| Geometric/Steric Descriptors | Coordination number, Atomic radius, Surface structure parameters, Steric maps | Crystallographic analysis, Topological modeling | Rationalizing steric effects in organometallic catalysis, nanoporous materials design [14] |

Interfacial Descriptors

Interfacial descriptors characterize the boundary regions between different phases or materials, which are critical in heterogeneous catalysis, electrocatalysis, and composite materials [16] [17].

Table 2: Key Interfacial Descriptors and Their Applications

| Descriptor Type | Specific Examples | Measurement/Calculation Methods | Catalytic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Descriptors | Interfacial Thermal Resistance (ITR), Thermal Boundary Conductance | Time-domain thermoreflectance (TDTR), Frequency-domain thermoreflectance (FDTR) | Thermal management in catalytic reactors, thermoelectric materials [16] |

| Mechanical Descriptors | Interface fracture toughness (Gic), Coefficient of friction (μ), Residual clamping stress (qo) | Single fiber pull-out/push-out tests, Micromechanical modeling | Composite catalyst design, catalyst-substrate interactions [17] |

| Electronic Interface Descriptors | Work function, Schottky barrier height, Interface dipole moment, Charge transfer amount | Kelvin probe force microscopy, DFT calculations, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy | Electrocatalyst design, semiconductor photocatalysis, hybrid catalyst systems [17] |

Reaction Pathway Descriptors

Reaction pathway descriptors characterize the progression of catalytic reactions, including energy landscapes, mechanistic steps, and selectivity-determining transitions [18] [14]. These descriptors are essential for understanding and optimizing catalytic cycles, particularly in complex reaction networks common in pharmaceutical synthesis.

Key reaction pathway descriptors include:

- Activation energy (Ea): The energy barrier for elementary reaction steps

- Reaction energy (ΔE): The energy difference between reactants and products

- Microkinetic parameters: Reaction rates and turnover frequencies (TOF)

- Selectivity descriptors: Energy differences between competing transition states

- Reaction coordinates: Geometric parameters tracing reaction progress

Experimental Protocols for Descriptor Determination

Protocol for Determining Interfacial Thermal Resistance

Principle: Interfacial Thermal Resistance (ITR) significantly impacts heat dissipation in catalytic reactors and thermoelectric materials. This protocol outlines standardized measurement using time-domain thermoreflectance (TDTR) [16].

Materials:

- Nanosecond or picosecond laser system (e.g., Ti:sapphire oscillator)

- Sample specimens with well-defined interfaces

- Metal transducer layer (80-100 nm aluminum)

- Radio-frequency lock-in amplifier

- Optical microscope for alignment

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Deposit a thin metal transducer layer (80-100 nm aluminum) on the catalyst surface using magnetron sputtering or electron-beam evaporation.

- Experimental Setup: Split the laser beam into pump and probe paths with controlled time delay. Focus both beams collinearly onto the transducer layer through an optical objective.

- Data Collection: Measure the thermoreflectance signal as a function of time delay (0-5 ns) at multiple locations (≥5) per sample.

- Model Fitting: Analyze data using the thermal diffusion model to extract ITR values, accounting for transducer thickness, beam spot sizes, and material thermal properties.

- Validation: Compare results with frequency-domain thermoreflectance (FDTR) measurements for consistency.

Data Interpretation: Lower ITR values indicate better thermal transport across interfaces, crucial for thermally stable catalytic systems. Typical ITR values range from 10-9 to 10-11 m2K/W for solid-solid interfaces [16].

Protocol for Determining Interface Fracture Toughness

Principle: This protocol determines interfacial fracture toughness (Gic) and frictional properties using single fiber pull-out tests, relevant for composite catalyst designs [17].

Materials:

- Universal testing machine with 10N load cell

- Single fiber composite specimens

- Optical microscope with digital image correlation

- Vacuum chamber for sample mounting

- High-resolution displacement transducer

Procedure:

- Specimen Preparation: Prepare model composite specimens with single fibers embedded in catalyst matrix material. Precisely measure embedded length (L) using optical microscopy.

- Mechanical Testing: Mount specimen in testing machine and apply tensile displacement at 0.1-0.5 mm/min until complete fiber pull-out occurs.

- Data Recording: Record load-displacement curves throughout the test, noting critical points: initial debond stress (σo), maximum debond stress (σd*), and initial frictional pull-out stress (σfr).

- Parameter Extraction: Calculate the interfacial fracture toughness using: σo = (4EfGic/a(1-2kνf))1/2 where Ef is fiber modulus, a is fiber diameter, and k is a materials constant [17].

- Friction Analysis: Determine the coefficient of friction (μ) from the stress decay profile using: λ = 2μk/a, where λ is derived from the initial slope of σfr vs. L at L=0.

Data Interpretation: Higher Gic values indicate tougher interfaces, while higher μ values suggest stronger frictional resistance, both contributing to mechanical stability in catalytic composites.

Protocol for Determining d-Band Center Electronic Descriptors

Principle: The d-band center theory correlates electronic structure with catalytic activity for transition metal catalysts. This protocol uses Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations to determine this critical electronic descriptor [11].

Materials:

- DFT computational package (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO)

- High-performance computing cluster

- Crystal structure files for catalyst materials

- Electron core potential databases

Procedure:

- Structure Optimization: Build atomic model of catalyst surface and perform full geometry optimization until forces converge to <0.01 eV/Å.

- Electronic Structure Calculation: Perform single-point energy calculation with high k-point density (>4000/atom) and hybrid functionals (e.g., HSE06) for accurate density of states (DOS).

- d-Band Center Calculation: Extract d-projected density of states (PDOS) and calculate d-band center using: εd = ∫Eρd(E)dE/∫ρd(E)dE, where ρd(E) is d-projected DOS.

- Validation: Compare calculated bulk properties (lattice parameters, band structure) with experimental values to verify computational accuracy.

- Correlation Analysis: Establish correlation between εd and catalytic performance metrics (activity, selectivity) for descriptor validation.

Data Interpretation: Higher d-band center values (closer to Fermi level) typically indicate stronger adsorbate binding and potentially higher catalytic activity, following the established d-band model [11].

Visualization of Descriptor Relationships and Workflows

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Descriptor Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Application Function | Key Suppliers/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Precursors | High-purity (>99.99%) salts (chlorides, nitrates, acetates) | Synthesis of model catalyst systems for descriptor determination | Sigma-Aldrich, Alfa Aesar [12] |

| Single Crystal Surfaces | Pre-oriented crystals (Pt(111), Au(100), Cu(110)) with surface roughness <0.1μm | Model surfaces for fundamental descriptor measurements | MaTecK, Princeton Scientific [11] |

| DFT Calculation Software | VASP, Gaussian, Quantum ESPRESSO with advanced functionals | Electronic descriptor calculation (d-band center, adsorption energies) [11] | Academic/licenses [11] [12] |

| High-Throughput Screening Platforms | Automated liquid handlers, parallel reactors with online GC/MS | Generation of large experimental datasets for ML model training [12] | Unchained Labs, Chemspeed [12] |

| Thermal Characterization Systems | TDTR/FDTR with nanosecond time resolution | Interfacial thermal resistance measurements | PulseForge, custom systems [16] |

| Microkinetic Modeling Software | CATKINAS, KinBot, RMG with validated mechanisms | Reaction pathway descriptor determination and analysis | Academic/open-source [18] [14] |

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Machine Learning Integration with Descriptors

The integration of machine learning with digital descriptors has created transformative opportunities in catalyst design [14] [12]. ML algorithms, including random forest, neural networks, and gradient boosting, utilize descriptors as input features to predict catalytic performance, substantially reducing the need for extensive trial-and-error experimentation [13] [14].

Successful implementations include:

- Predictive activity models: Using electronic and steric descriptors to forecast catalytic yields and selectivity with >90% accuracy in cross-validation [14]

- High-throughput screening: Combining descriptor-based ML with robotic experimentation to evaluate thousands of catalyst formulations [12]

- Descriptor importance analysis: Identifying which structural features most significantly impact catalytic performance for targeted optimization [12]

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in the field of digital descriptors for catalysis. Future research directions include:

Data quality and standardization: Developing unified protocols for descriptor calculation and measurement to ensure reproducibility and transferability across studies [19] [12].

Dynamic descriptor development: Creating descriptors that capture time-dependent and reaction-condition-dependent changes in catalytic systems [15].

Multi-scale integration: Bridging descriptors across length scales from atomic to mesoscale to macroscopic performance [11] [12].

Experimental validation: Ensuring theoretical descriptor predictions are consistently validated through well-designed experiments [14] [12].

The continued refinement of digital descriptors, coupled with advances in machine learning and high-throughput experimentation, promises to accelerate catalyst discovery and optimization, ultimately enabling more sustainable and efficient chemical processes for pharmaceutical and industrial applications.

Application Notes

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into predictive catalysis is transforming the empirical landscape of catalyst research, enabling the rapid in-silico identification and optimization of novel materials. Each AI paradigm offers distinct advantages: Classical Machine Learning (ML) provides high interpretability for well-defined problems with structured data, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) naturally model molecular structures to predict complex structure-activity relationships, and Large Language Models (LLMs) can process diverse, unstructured data formats like text descriptions to uncover latent patterns [20] [21] [22]. The selection of an appropriate paradigm is critical and depends on the specific research goal, data availability, and the required balance between precision and interpretability.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of each paradigm in the context of catalyst design.

Table 1: Comparison of AI Paradigms in Predictive Catalysis

| Feature | Classical Machine Learning (ML) | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Large Language Models (LLMs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Input | Structured tabular data (e.g., descriptors, properties) [20] | Graph-structured data (e.g., molecular graphs) [22] [23] | Sequential/text data (e.g., SMILES, textual descriptions) [21] [3] |

| Typical Model Examples | Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests, Neural Networks [24] | HCat-GNet, CGCNN, MEGNet [21] [22] | T5, BERT, GPT-based architectures [21] [25] |

| Key Strength | High interpretability, lower computational cost, effective with smaller, curated datasets [20] [24] | Native handling of molecular topology; excellent for property prediction [22] [23] | Flexibility with input data; can learn from vast scientific corpora [21] [25] |

| Main Limitation | Requires manual, expert-driven feature engineering (descriptor calculation) [24] [26] | High computational demand; less interpretable than Classical ML [22] | "Black box" nature; high risk of hallucinations; massive data requirements [27] [21] |

| Ideal Catalyst Use Case | Predicting selectivity/activity from a defined set of quantum chemical descriptors [24] [26] | Predicting enantioselectivity or material properties directly from molecular structure [22] | Predicting crystal properties from text descriptions or automating scientific literature analysis [21] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Classical ML in Enantioselectivity Prediction

This protocol outlines the use of Support Vector Machines (SVMs) for predicting catalyst enantioselectivity, based on a chemoinformatic workflow [24].

1. Objective: To build a predictive model for the enantiomeric excess (ee) of chiral phosphoric acid-catalyzed reactions using steric and electronic molecular descriptors.

2. Reagent Solutions:

- Software: Python with scikit-learn, RDKit, or similar chemoinformatics libraries.

- Computer System: Standard workstation (CPU-intensive calculations).

3. Procedure: * Step 1 - Construct In-Silico Catalyst Library: Generate a virtual library of synthetically accessible catalyst structures derived from a central scaffold [24]. * Step 2 - Calculate 3D Molecular Descriptors: For each catalyst candidate, compute robust three-dimensional molecular descriptors that quantify steric and electronic properties. This may involve generating an ensemble of conformers [24]. * Step 3 - Select Universal Training Set (UTS): Apply a training set selection algorithm (e.g., based on principal components analysis) to choose a representative subset of catalysts that maximizes the diversity of feature space covered. This UTS is reaction-agnostic [24]. * Step 4 - Acquire Experimental Training Data: Synthesize the catalysts in the UTS and experimentally determine their enantioselectivity in the target reaction [24]. * Step 5 - Train SVM Model: Use the calculated descriptors as input features and the experimental enantioselectivity (e.g., ΔΔG‡) as the target variable to train a Support Vector Machine model [24]. * Step 6 - Validate Model: Evaluate the trained model on an external test set of catalysts not included in the training data. Performance is typically reported as Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) in kcal/mol [24].

Protocol for GNN in Ligand Optimization

This protocol details the use of a specialized GNN, HCat-GNet, for predicting enantioselectivity and aiding ligand design [22].

1. Objective: To predict the enantioselectivity (ΔΔG‡) of an asymmetric Rhodium-catalyzed 1,4-addition and identify ligand motifs that influence selectivity.

2. Reagent Solutions:

- Software: HCat-GNet implementation (Python/PyTorch Geometric).

- Computer System: Modern workstation with a GPU (e.g., NVIDIA RTX series) for accelerated training.

3. Procedure: * Step 1 - Data Curation: Compile a dataset of known reactions, including the SMILES strings of the substrate, reagent, chiral ligand, and the measured enantioselectivity [22]. * Step 2 - Graph Representation: Convert each participant molecule into a graph. Nodes represent atoms, encoded with features (atom type, degree, hybridization, chirality). Edges represent bonds [22]. * Step 3 - Create Reaction Graph: Concatenate the individual molecular graphs into a single, disconnected reaction-level graph [22]. * Step 4 - Model Training: Train the HCat-GNet on the reaction graphs to predict the ΔΔG‡ value. The model uses message-passing to learn a complex representation of the reaction [22]. * Step 5 - Explainability Analysis: Apply explainable AI (XAI) techniques (e.g., visualization of atom-level attention) to the trained model. This highlights which specific atoms in the ligand contribute most to high or low predicted selectivity, providing a guide for rational ligand design [22].

Protocol for LLM in Crystal Property Prediction

This protocol, based on the LLM-Prop framework, describes fine-tuning a transformer model to predict properties of crystalline materials from their text descriptions [21].

1. Objective: To predict the band gap and formation energy of a crystal from its textual description.

2. Reagent Solutions:

- Software: Hugging Face Transformers library, TensorFlow/PyTorch.

- Pre-trained Model: T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) model.

- Dataset: TextEdge benchmark dataset containing crystal text descriptions and their properties [21].

3. Procedure:

* Step 1 - Data Preprocessing:

* Remove common stopwords from the text descriptions [21].

* Replace specific numerical values (e.g., bond distances and angles) with special tokens [NUM] and [ANG] to reduce vocabulary complexity and improve model focus on contextual information [21].

* Prepend a [CLS] token to the input sequence to aggregate sequence-level information for prediction [21].

* Step 2 - Model Adaptation: For predictive (regression/classification) tasks, discard the decoder of the standard T5 model. Add a linear regression (or classification) head on top of the encoder's [CLS] token output [21].

* Step 3 - Fine-tuning: Fine-tune the encoder and the new prediction layer on the TextEdge dataset, using mean squared error (for regression) as the loss function [21].

* Step 4 - Evaluation: Compare the model's performance against state-of-the-art GNN-based property predictors on metrics like Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [21].

Workflow Visualization

AI Paradigm Selection Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for AI-Driven Catalyst Research

| Reagent / Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Catalysis Research |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn | Software Library | Provides robust implementations of Classical ML algorithms (SVMs, Random Forests) for building predictive models from descriptor data [24]. |

| RDKit | Software Library | An open-source toolkit for chemoinformatics used to calculate molecular descriptors, handle SMILES strings, and manipulate molecular structures [24]. |

| HCat-GNet | Specialized GNN Model | A Graph Neural Network designed specifically for predicting enantioselectivity in homogeneous catalysis from molecular graphs, offering high interpretability [22]. |

| T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) | LLM Architecture | A transformer-based model that can be adapted for predictive tasks (like crystal property prediction) by using its encoder with a custom prediction head [21]. |

| TextEdge Dataset | Benchmark Data | A public dataset containing text descriptions of crystals and their properties, used for training and benchmarking LLMs for materials informatics [21]. |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) | Reaction Database | A broad collection of reaction data used for pre-training generative and predictive models, enabling transfer learning to specific catalytic problems [3]. |

AI in Action: Techniques and Workflows for Predicting Catalyst Performance

High-Throughput Virtual Screening of Catalyst Libraries

The discovery and optimization of catalysts have traditionally relied on empirical, trial-and-error approaches, which are often time-consuming and resource-intensive [28] [24]. High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) represents a paradigm shift, leveraging computational power and machine learning to rapidly evaluate vast libraries of potential catalyst structures in silico before any laboratory synthesis [29]. This methodology is a cornerstone of predictive modeling for catalyst activity and selectivity research, enabling researchers to navigate chemical space more efficiently and rationally [30]. By using computational models as surrogates for expensive experiments or simulations, HTVS accelerates the identification of promising catalysts for a wide range of applications, from asymmetric synthesis to electrocatalysis [24] [29].

This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for implementing HTVS, framed within the broader context of predictive catalyst design. It is structured to guide researchers and drug development professionals through the essential components of a successful HTVS campaign.

Key Concepts and Strategic Approaches

High-Throughput Virtual Screening can be broadly categorized into several strategic approaches, each with its own strengths and application domains.

Table 1: Strategic Approaches to High-Throughput Virtual Screening in Catalysis

| Approach | Description | Primary Use Case | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) | Docks small molecules into the 3D structure of a target (e.g., an enzyme or catalytic surface) to predict binding affinity and complementarity [31]. | Targets with known 3D structures (experimentally determined or via homology modeling) [31]. | Directly evaluates physical complementarity; can find novel scaffolds beyond training data [32]. |

| Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS) | Uses known active or inactive compounds to retrieve other potentially active molecules based on similarity, pharmacophore mapping, or Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models [31]. | Targets with limited 3D structural data but existing bioactivity data [31]. | Does not require a 3D target structure; can leverage historical assay data effectively. |

| Machine Learning (ML)-Guided Screening | Employs ML models trained on computational (e.g., DFT) or experimental data to predict catalytic performance metrics (activity, selectivity) for new structures [30] [29]. | Large, diverse chemical spaces where rapid property prediction is needed [33] [29]. | Extremely high speed (~200,000x faster than DFT); can identify complex, non-obvious structure-activity relationships [29]. |

| Inverse Design | Uses generative models conditioned on desired target properties to create novel catalyst structures from scratch [29]. | Designing catalysts with multi-objective, tailored performance characteristics [29]. | Explores chemical space creatively; can propose unconventional materials not considered by human intuition [29]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

General HTVS Workflow for Catalyst Discovery

The following diagram illustrates a generalized, robust workflow for a high-throughput virtual screening campaign aimed at catalyst discovery. This workflow integrates elements from various successful implementations cited in the literature [33] [24] [29].

Protocol 1: Machine Learning-Guided Screening with a Universal Training Set

This protocol details a chemoinformatics-driven workflow for predicting enantioselectivity, as exemplified by the work of Sigman and co-workers [24].

Step 1: Construct an In-Silico Catalyst Library

- Objective: Generate a large, synthetically accessible library of catalyst candidates based on a specific scaffold (e.g., chiral phosphoric acids) [24].

- Methodology: Use computational structure enumeration to systematically vary substituents, creating a virtual library of thousands to millions of conceivable structures.

Step 2: Calculate 3D Molecular Descriptors

- Objective: Quantify the steric and electronic properties of each catalyst candidate [24].

- Methodology: For each catalyst structure in the library, generate an ensemble of conformers. Then, calculate robust, 3D molecular descriptors (e.g., Sterimol parameters, partial charges, molecular interaction fields) that are agnostic to the underlying scaffold [24].

Step 3: Select a Universal Training Set (UTS)

- Objective: Choose a representative subset of catalysts for experimental testing that maximizes the diversity of feature space covered by the descriptors [24].

- Methodology: Apply training set selection algorithms (e.g., sphere exclusion, k-means clustering) on the descriptor matrix. This ensures the UTS is mechanism- and reaction-agnostic and can be used to optimize any reaction catalyzed by that scaffold [24].

Step 4: Acquire Experimental Training Data

- Objective: Collect high-quality enantioselectivity data (e.g., enantiomeric excess or ee) for the UTS catalysts in the reaction of interest [24].

- Methodology: Synthesize the catalysts in the UTS and test them under standardized reaction conditions. Convert selectivity data into a free energy difference (ΔΔG‡) for model training.

Step 5: Train Machine Learning Models

- Objective: Build a model that maps molecular descriptors to catalytic selectivity [24].

- Methodology: Use machine learning algorithms such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) or Deep Feed-Forward Neural Networks. Train the model on the UTS data (descriptors as input, ΔΔG‡ as output). Validate the model's predictive power using external test sets of catalysts not included in the training [24].

Step 6: Screen Library and Select Leads

- Objective: Identify the most promising catalyst candidates from the full in-silico library.

- Methodology: Use the trained model to predict the selectivity of every member of the full library. Rank the candidates based on predicted performance and select the top-ranked compounds for synthesis and experimental validation [24].

Protocol 2: Ultra-High-Throughput Ligand-Based Screening with AI

This protocol is based on the BIOPTIC B1 system, which demonstrates the screening of tens of billions of compounds for rapid hit identification [33].

Step 1: Model Preparation and Library Indexing

- Objective: Establish a system for rapid similarity searching in ultra-large chemical spaces.

- Methodology:

- Pre-train a transformer model (e.g., RoBERTa-style) on a large corpus of chemical structures (e.g., PubChem and Enamine REAL space) [33].

- Fine-tune the model on bioactivity data (e.g., from BindingDB) to learn potency-aware molecular embeddings [33].

- Map each molecule in the screening library (e.g., 40 billion compounds) to a low-dimensional vector (e.g., 60 dimensions). Pre-index these vectors for fast retrieval [33].

Step 2: Query Submission and Screening Execution

- Objective: Identify structures similar to known active compounds.

- Methodology: Use one or more known active inhibitors or catalysts as query structures. The system converts the query into an embedding and performs a Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD)-optimized cosine similarity search over the pre-indexed library. This allows for the retrieval of potential leads from 40 billion compounds in a few minutes per query using CPU-only resources [33].

Step 3: Hit Prioritization and Triage

- Objective: Filter retrieved compounds to select the most promising candidates for synthesis.

- Methodology: Apply strict novelty filters (e.g., Tanimoto coefficient ≤0.4 to any known active in databases like BindingDB) and liability filters (e.g., REOS, PAINS). Prioritize compounds based on predicted potency, desirable physicochemical properties (e.g., CNS-likeness for neuro-targets), and synthetic accessibility [33].

Step 4: Rapid Synthesis and Validation

- Objective: Experimentally confirm the activity of predicted hits.

- Methodology: Collaborate with a partner (e.g., Enamine) for rapid, parallel synthesis of the selected candidates. In the reported LRRK2 case study, 134 predicted leads were synthesized with a 93% success rate in an 11-week cycle. Confirm binding and activity using relevant assays (e.g., KINOMEscan for kinase targets) [33].

Performance Metrics and Data Analysis

Quantitative assessment is critical for evaluating the success of an HTVS campaign. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent landmark studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Representative HTVS Campaigns

| Screening Focus / System | Library Size Screened | Key Computational Performance | Experimental Validation Results | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRRK2 Inhibitors (BIOPTIC B1) | 40 billion compounds | CPU search time: ~2.15 min per query; estimated cost ~$5 per screen [33]. | 87 compounds tested → 4 binders (Kd ≤ 10 µM); best Kd = 110 nM. 21% hit rate from analog expansion [33]. | [33] |

| Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) Catalysts | 6,155 spinel oxides (DFT), 132 new candidates (ML) | ML model R² = 0.92; prediction speed ~200,000x faster than DFT [29]. | Top ML-predicted hit (Co₂.₅Ga₀.₅O₄) synthesized and matched benchmark performance (220 mV overpotential) [29]. | [29] |

| CO₂ Reduction (MAGECS Inverse Design) | ~250,000 generated structures | Generative model achieved 2.5x increase in high-activity candidate proportion [29]. | 5 new alloys synthesized; 2 (Sn₂Pd₅, Sn₉Pd₇) showed ~90% faradaic efficiency for formate [29]. | [29] |

| Chiral Phosphoric Acid Catalysts | In-silico library of a specific scaffold | Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) of 0.161 - 0.236 kcal/mol for external test sets [24]. | Accurate prediction of enantioselectivity for catalysts and substrates not in the training data [24]. | [24] |

Successful implementation of HTVS relies on a combination of computational tools, data resources, and physical compound libraries.

Table 3: Essential Resources for High-Throughput Virtual Screening

| Resource Category | Example / Product | Description and Function | Key Features / Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Data Repositories | PubChem [34] | A public repository of chemical structures and their biological activities. Used to obtain training data and chemical structures. | >60 million unique chemical structures; >1 million biological assays [34]. |

| Commercial Compound Libraries | MCE Virtual Screening Compound Library [31] | A purchasable compound library for virtual screening and follow-up experimental testing. | 10 million screening compounds from 18+ manufacturers [31]. |

| Software & Web Services | Schrödinger Virtual Screening Web Service [32] | A cloud-based service that combines physics-based docking (Glide) with machine learning to screen ultra-large libraries. | Screens >1 billion compounds in one week; includes built-in pilot study validation [32]. |

| Computational Descriptors | Sterimol Parameters, SambVca [30] [24] | Robust 3D molecular descriptors that quantify steric and electronic properties of catalysts, crucial for building predictive QSAR models. | Scaffold-agnostic; capture subtle features responsible for enantioinduction [24]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Support Vector Machines (SVM), Deep Neural Networks [24] | Algorithms used to train predictive models that map catalyst descriptors to performance outcomes like selectivity and activity. | Capable of accurately predicting outcomes far beyond the selectivity regime of the training data [24]. |

Administrative Information

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Title | Predictive Modeling of Performance Metrics: Activity, Selectivity, and Yield {1} |

| Trial Registration | Not applicable. This protocol outlines a computational research methodology. {2a and 2b} |

| Protocol Version | 1.0, November 2025 {3} |

| Funding | This work is supported by [Name of Funder and Grant Number, if applicable]. {4} |

| Author Details | [Names and affiliations of protocol contributors]. {5a} |

| Role of Sponsor | The study sponsor had no role in the study design; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. {5c} |

Background

Predictive modeling has transformed the assessment of catalyst performance by addressing complex, high-dimensional challenges in optimizing heterogeneous catalysts. Traditional experimental approaches are often resource-intensive and limit the scope of material exploration [6].

Methods

This protocol details a machine learning (ML) workflow integrating density functional theory (DFT) computations, feature engineering, and interpretable AI models like XGBoost and SHAP analysis. The process includes data compilation, model training for predicting key performance metrics (activity, selectivity, yield), and validation through statistical and comparative analysis [6] [35].

Discussion

This structured approach accelerates catalyst discovery by establishing accurate links between material features and catalytic performance, enabling precise property predictions and the systematic identification of promising candidates [6].

Trial registration

Not applicable.

Background and Rationale

The development of highly active and durable catalysts is critical for energy technologies and chemical synthesis. Traditionally, catalyst development has relied on extensive trial-and-error experimentation, often limited by reproducibility and narrow material exploration. Predictive modeling, driven by machine learning, allows catalytic activity and selectivity to be estimated prior to experimentation, significantly accelerating technological advancements [6]. For complex systems like high-entropy alloys (HEAs), establishing structure-performance relationships is a grand challenge due to the vast number of possible active sites, making ML frameworks essential for rational design [35].

Objectives

The primary objective of this protocol is to provide a standardized framework for using predictive models to screen and optimize catalysts based on activity, selectivity, and yield. Specific objectives include:

- Establishing accurate links between electronic/geometric features and catalytic performance.

- Identifying critical descriptors governing catalyst activity and selectivity.

- Enabling rapid screening of vast material spaces to identify promising candidates.

Trial Design

This protocol describes a computational, in silico study design for catalyst screening and optimization. The framework is based on a retrospective analysis of existing datasets and prospective generative design [6].

Methods: Data and Workflow

Study Setting

All computational work is performed using high-performance computing (HPC) resources. Software includes VASP for DFT calculations and Python-based ML libraries (e.g., scikit-learn, XGBoost, SHAP) [35].

Data Compilation and Feature Engineering {18a}

A comprehensive dataset is compiled, typically consisting of hundreds of unique catalyst entries [6]. For each catalyst, the following data is recorded as shown in Table 1 [6] [35].

Table 1: Example Data Structure for Catalyst Performance Modeling

| Catalyst ID | Adsorption Energy C (eV) | Adsorption Energy O (eV) | d-band Center (eV) | d-band Filling | d-band Width (eV) | Compositional Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cat_1 | -1.20 | -2.10 | -2.05 | 0.75 | 4.50 | [Feature Vector] |

| Cat_2 | -0.95 | -1.85 | -2.30 | 0.80 | 4.30 | [Feature Vector] |

Outcomes {12}: The primary outcomes are the predicted values for activity, selectivity, and yield descriptors, such as the binding energies of key reaction intermediates (e.g., *CO, *H, *CHO) [35].

Participant Timeline {13}: The workflow timeline is as follows: Data Collection → Feature Engineering → Model Training & Validation → Interpretation & Screening → Output of Candidate Materials.

Machine Learning Models and Statistical Methods {20a}

ML Regression Models: The XGBRegressor algorithm is utilized to build prediction models for target properties like binding energies. The mean square error (MSE) is adopted to evaluate model performance. 5-fold cross-validation is employed to mitigate bias from data splitting [35].

Interpretable AI: SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis is performed to quantify the marginal contribution of each feature to the model's predictions, breaking the "black box" nature of ML models [6] [35].

Generative Models: Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) can be employed to synthesize data and explore uncharted material spaces [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Resources

| Item | Function / Description | Example Tools / Values |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Software | Calculates fundamental electronic properties and adsorption energies. | VASP [35] |

| ML Algorithms | Builds predictive models for catalyst properties. | XGBRegressor, XGBClassifier [35] |

| Interpretability Package | Explains model predictions and identifies critical features. | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [6] [35] |

| Descriptor Features | Numerical representations of catalyst structure and composition. | d-band center, d-band filling, d-band width, elemental composition vectors [6] [35] |

| Color Palette | Ensures accessibility and clarity in data visualizations. | Hex Codes: #4285F4, #EA4335, #FBBC05, #34A853, #FFFFFF, #F1F3F4, #202124, #5F6368 |

Workflow Visualization

Workflow Diagram

Results and Discussion

Data Presentation and Model Performance

After model training, performance is evaluated. The following table summarizes typical results for predicting adsorption energies, a key activity metric [6] [35].

Table 3: Example Machine Learning Model Performance Metrics

| Target Intermediate | ML Model | Mean Square Error (MSE) | Key Performance Descriptor |

|---|---|---|---|

| *CO | XGBRegressor | 0.08 eV² | d-band center, d-band upper edge [6] |

| *CHO | XGBRegressor | 0.10 eV² | d-band filling [6] |

| *H | XGBRegressor | 0.05 eV² | d-band center, d-band filling [6] |

Feature Importance and Interpretation

SHAP analysis is used to identify the electronic-structure descriptors that most critically determine adsorption energies and, consequently, catalytic performance. For instance, d-band filling is often critical for the adsorption energies of carbon (C), oxygen (O), and nitrogen (N), while the d-band center and upper edge are more significant for hydrogen (H) binding [6]. This interpretability is crucial for guiding rational catalyst design rather than relying on black-box predictions.

Method Validation

Validation Techniques

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Provides a robust framework for uncovering the underlying structure and dominant patterns in the dataset, summarizing electronic structure features [6].

- Benchmarking against Experimental Data: Constructed descriptors should be validated by accurately predicting performance variations reported in experiments [35].

- Bayesian Optimization: Used to refine predictions and navigate the complex parameter space for optimal catalyst composition [6].

- Mashayekhi, A., et al. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 2025, 705, 120434 [6].

- Sun, J., et al. Chem. Sci., 2025, Advance Article [35].

Inverse design represents a paradigm shift in catalyst development, moving from traditional trial-and-error approaches to a targeted, property-to-structure methodology. Framed within the broader context of predictive modeling for catalyst activity and selectivity research, this approach uses computational models to generate catalyst structures predicted to exhibit specific, desirable performance metrics. By leveraging machine learning (ML) and chemoinformatics, researchers can now navigate the vast chemical space of possible catalyst candidates with unprecedented efficiency, accelerating the discovery of high-performance materials for applications ranging from pharmaceutical synthesis to sustainable energy conversion.

The core principle of inverse design is the reversal of the conventional structure-to-property pipeline. Instead of synthesizing a catalyst and then measuring its properties, researchers start by defining the target properties—such as high enantioselectivity or optimal adsorption energy—and then use generative models to identify candidate structures that fulfill these criteria. This data-driven approach is particularly valuable in asymmetric catalysis, where subtle structural changes in a catalyst can lead to significant differences in selectivity, and traditional optimization is often hindered by the limitations of human intuition in recognizing complex, multi-parametric patterns in large datasets [24].

Foundational Methodologies in Catalytic Inverse Design

The implementation of inverse design relies on several interconnected methodological pillars: robust molecular representation, generative model architectures, and strategic training set construction.

Molecular Representation and Feature Encoding

Accurately representing a catalyst's structure in a format digestible by machine learning models is a critical first step. The chosen molecular descriptors must capture the three-dimensional steric and electronic properties that govern catalytic activity and selectivity.

- 3D Molecular Descriptors: Effective descriptors quantify the steric and electronic properties of thousands of candidate molecules without requiring prior mechanistic understanding. These are numerical representations derived from the 3D molecular structure [24].

- Topological Descriptors: For complex systems like high-entropy alloy (HEA) catalysts, advanced tools like Persistent GLMY Homology (PGH) can be employed. PGH provides a refined, topological characterization of the three-dimensional spatial features of catalytic active sites, quantifying both coordination effects (spatial arrangement of atoms) and ligand effects (random spatial distribution of different elements) [36].

- RDKit and Structural Fingerprints: In the context of ligand design, libraries like RDKit can be used to calculate molecular descriptors, enabling the model to learn and generate chemically valid and synthetically accessible structures [37].

Generative Model Architectures

Several deep learning architectures have been adapted for the generative task of creating novel catalyst structures.

- Deep-Learning Transformers: In the inverse design of vanadyl-based catalyst ligands, the transformer architecture demonstrated high performance, achieving high validity (64.7%), uniqueness (89.6%), and similarity (91.8%) for the generated structures [37].

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs): A topology-based VAE framework (PGH-VAEs) has been developed for the interpretable inverse design of catalytic active sites on HEAs. This multi-channel model separately encodes coordination and ligand effects, allowing the latent design space to possess substantial physical meaning [36].

- Diffusion Models: While successfully applied to crystalline materials and molecules, diffusion models for amorphous materials (e.g., the Amorphous Material DEnoising Network, AMDEN) are an emerging area of development, facing challenges due to limited large-scale datasets and the requirement for larger simulation cells [38].

Training Set Selection and Data Augmentation

The performance of generative models is heavily dependent on the quality and scope of the training data. A carefully selected training set ensures the model can generalize across a wide chemical space.

- Universal Training Set (UTS): A UTS is a representative subset of catalyst candidates selected from a large in silico library. It is agnostic to reaction or mechanism, meaning it can be used to optimize any reaction catalyzed by that particular catalyst scaffold. This selection is based on ensuring maximal coverage of the feature space defined by the molecular descriptors [24].

- Semi-Supervised Learning: To overcome the scarcity of expensive-to-acquire data (e.g., from Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations), a semi-supervised approach can be highly effective. A model is first trained on a limited set of labeled DFT data. This model is then used to predict the properties of a large, unlabeled database of generated structures, effectively augmenting the dataset used for training the final generative model [36].

Application Notes and Protocols

This section provides a detailed, practical guide for implementing an inverse design workflow, illustrated with a specific case study.

Case Study: Inverse Design of a Chiral Phosphoric Acid Catalyst

The following workflow, adapted from a study on predicting higher-selectivity catalysts, outlines the process for the inverse design of a chiral phosphoric acid catalyst for the enantioselective addition of thiols to N-acylimines [24].

Experimental Workflow:

The diagram below visualizes the multi-stage inverse design protocol for chiral catalyst selection.

Protocol 1: In Silico Library Construction and UTS Selection

- Objective: To generate a comprehensive virtual library of synthetically accessible catalyst candidates and select a representative subset for experimental testing.

- Materials:

- Computer with molecular modeling software (e.g., Schrodinger Maestro, Open Babel).

- Scripting environment (e.g., Python with RDKit library).

- Procedure:

- Library Generation: Define the core scaffold of the chiral phosphoric acid. Systematically enumerate possible substituents at the varying positions, focusing on groups that are synthetically feasible. This can generate a library of thousands to millions of virtual candidates [24].

- Descriptor Calculation: For every candidate in the library, calculate relevant 3D molecular descriptors. These should capture steric (e.g., Sterimol parameters, molar volume) and electronic (e.g., Hammett parameters, partial charges) properties [24].

- UTS Selection: Use a clustering algorithm (e.g., k-means) or a distance-based selection method (e.g., Kennard-Stone) on the principal components of the descriptor space to identify 20-50 catalysts that maximally span the chemical space of the entire library. This set is the UTS [24].

- Notes: The quality of the UTS is critical for the subsequent model's predictive power and its ability to generalize.

Protocol 2: Model Training and Catalyst Prediction

- Objective: To train a machine learning model on experimental data from the UTS and use it to predict the performance of all candidates in the in silico library.

- Materials:

- Experimentally determined enantiomeric excess (ee) values for the UTS catalysts.

- Machine learning software environment (e.g., Python with scikit-learn, TensorFlow).

- Procedure:

- Data Collection: Synthesize the UTS catalysts and obtain their experimental enantioselectivities (as ee% or ΔΔG‡) for the target reaction.

- Model Training: Train a machine learning model—such as a Support Vector Machine (SVM) or a Deep Feed-Forward Neural Network—using the molecular descriptors of the UTS as input and the experimental selectivity data as the output [24].

- Model Validation: Validate the model using an external test set of catalysts not included in the UTS. The model demonstrated a Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) of approximately 0.21-0.24 kcal/mol for predicting the selectivity of external catalysts [24].

- Virtual Screening: Use the trained model to predict the selectivity of every candidate in the original in silico library. Rank the candidates based on their predicted performance.

- Notes: This protocol can successfully identify highly selective catalysts even when the training data contains no reactions with selectivity above 80% ee, effectively predicting performance beyond the bounds of the training data [24].

Quantitative Performance of Inverse Design Models

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent inverse design studies in catalysis.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Inverse Design Models in Catalysis

| Catalyst System | Generative Model | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vanadyl-based Ligands | Deep-learning Transformer | Validity: 64.7%, Uniqueness: 89.6%, RDKit Similarity: 91.8% | [37] |

| Chiral Phosphoric Acids | Support Vector Machine / Neural Networks | Prediction MAD: 0.161 - 0.236 kcal/mol | [24] |

| HEA Active Sites (*OH adsorption) | Topological VAE (PGH-VAEs) | Prediction MAE: 0.045 eV (using ~1100 DFT data points) | [36] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and experimental resources essential for conducting inverse design in catalysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Catalytic Inverse Design

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for calculating molecular descriptors, fingerprinting, and operating on molecules. | Critical for generating and validating molecular structures in silico [37]. |

| DFT Calculations | Density Functional Theory provides high-fidelity data on adsorption energies, reaction mechanisms, and electronic structures for training and validation. | Computationally expensive; often used sparingly to generate a core dataset [30] [36]. |

| Universal Training Set (UTS) | A strategically selected, minimal set of catalyst candidates that maximally spans the chemical space of a larger virtual library. | Enables efficient data acquisition; agnostic to reaction mechanism [24]. |

| Sterimol Parameters | 3D steric bulk descriptors (L, B1, B5) used to quantify the shape and size of substituents on a catalyst. | Provides a more accurate picture of molecular behavior in solution than simple volume metrics [24]. |

| Persistent GLMY Homology (PGH) | An advanced topological analysis tool for quantifying the 3D structural features and sensitivity of complex active sites, such as those in HEAs. | Captures both coordination and ligand effects from a colored point cloud of atoms [36]. |

Inverse design has firmly established itself as a powerful, data-driven framework for the discovery and optimization of catalyst structures. By leveraging generative machine learning models, robust molecular descriptors, and strategic experimental design, this approach directly addresses the core challenges of predictive modeling in catalyst activity and selectivity research. The methodologies outlined—from transformer-based ligand generation to topology-based VAEs for active sites—demonstrate a scalable and efficient path to catalyst design. As these techniques continue to mature and integrate more deeply with automated synthesis and testing platforms, they hold the promise of fundamentally changing the landscape of catalytic research, moving the field from empirical guesswork to mathematically guided, on-demand discovery.

Automated Discovery of Catalytic Mechanisms and Transition States

The rational design of catalysts has long been a fundamental challenge in chemistry, pivotal for advancing sustainable synthesis, energy technologies, and pharmaceutical development. Traditional approaches to understanding catalytic mechanisms, particularly the identification of transition states (TSs)—the highest-energy points along a reaction pathway—have relied heavily on empirical methods and computationally intensive quantum mechanical calculations. These methods, while valuable, are often slow, resource-demanding, and impractical for navigating the vast complexity of chemical space. The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and automated high-throughput computation is now revolutionizing this field, enabling the predictive modeling of catalyst activity and selectivity with unprecedented speed and accuracy [30] [39]. This paradigm shift moves catalyst design from a trial-and-error process to a rational, data-driven science. These technologies are not merely incremental improvements; they represent a transformative approach that integrates automation, machine learning (ML), and robotics into a cohesive workflow for the discovery of catalytic mechanisms and transition states [40] [14]. This article details the key protocols and tools powering this new era of automated discovery, framed within the broader objective of predictive modeling in catalysis research.

Core Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Automated Transition State Location with AutoTS

Locating transition states is essential for computing activation energies and understanding reaction rates, yet these states cannot be observed experimentally [41]. The AutoTS workflow is an automated computational solution designed to find transition states for elementary, molecular reactions.