Bayesian Optimization for Catalyst Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide for Accelerated Materials and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Bayesian Optimization (BO) for optimizing catalyst composition, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Bayesian Optimization for Catalyst Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide for Accelerated Materials and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Bayesian Optimization (BO) for optimizing catalyst composition, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of BO as a powerful machine learning strategy for navigating complex experimental spaces with minimal trials. The guide explores cutting-edge methodological advances, including in-context learning with large language models and multi-task learning, alongside practical applications in heterogeneous catalysis and pharmaceutical synthesis. It also addresses common troubleshooting challenges and presents rigorous validation frameworks through comparative case studies, demonstrating how BO achieves significant efficiency gains—often identifying optimal catalysts with 10-90% fewer experiments compared to traditional high-throughput screening.

The Core Principles of Bayesian Optimization in Catalyst Discovery

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is Bayesian Optimization and when should I use it? Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a sequential design strategy for the global optimization of black-box functions that are expensive to evaluate and do not assume any functional forms [1]. It is particularly suited for tuning hyperparameters in machine learning [2], optimizing experimental conditions in drug development [3], and designing new materials, such as catalysts [4].

What are the core components of the BO algorithm? The BO algorithm consists of two key components:

- Probabilistic Surrogate Model: A model, typically a Gaussian Process (GP), used to approximate the unknown objective function. It provides a posterior distribution that captures beliefs about the function's behavior and uncertainty at unsampled points [3] [5].

- Acquisition Function: A function that guides the selection of the next point to evaluate by balancing the exploration of uncertain regions with the exploitation of promising ones. Common examples include Expected Improvement (EI), Probability of Improvement (PI), and Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [1] [6].

Why is my BO algorithm converging slowly or to a poor solution? Slow or poor convergence can stem from several common pitfalls [3]:

- Incorrect Prior Width: Misspecifying the prior in your surrogate model can lead to an inaccurate representation of the objective function.

- Over-smoothing: This occurs when the surrogate model (e.g., using a standard GP) fails to capture non-smooth patterns or sharp transitions in the true function.

- Inadequate Acquisition Maximization: If the inner optimization loop that finds the maximum of the acquisition function is not performed thoroughly, it may choose suboptimal points.

How do I choose the right acquisition function? The choice involves a trade-off between exploration and exploitation [2] [6]:

- Expected Improvement (EI): A popular, general-purpose choice that balances both by measuring the average amount by which a point is expected to improve over the current best observation [3].

- Upper Confidence Bound (UCB): Good when you need explicit control over the exploration-exploitation trade-off via its

βparameter [3]. - Probability of Improvement (PI): More exploitative; selects points with the highest probability of improving over the current best, which can sometimes lead to getting stuck in local optima [2].

Can BO handle high-dimensional problems, like optimizing a catalyst with multiple elements? Standard BO is often limited to problems with fewer than 20 dimensions [1] [5]. However, recent advancements, such as the Sparse Axis-Aligned Subspace Bayesian Optimization (SAASBO) algorithm, use structured priors to effectively handle problems with hundreds of dimensions by assuming only a sparse subset of parameters is truly relevant [5]. This makes BO a viable tool for optimizing complex, high-dimensional catalyst compositions [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Algorithm gets stuck in a local optimum This is a classic sign of over-exploitation, where the BO process fails to explore the parameter space sufficiently.

- Potential Causes & Solutions

- Cause 1: The acquisition function (e.g., Probability of Improvement) is too greedy.

- Solution: Switch to the Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function, which more naturally balances exploration and exploitation. You can also adjust the

ϵparameter in PI to force more exploration, though tuning it can be challenging [2].

- Solution: Switch to the Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function, which more naturally balances exploration and exploitation. You can also adjust the

- Cause 2: The surrogate model's kernel length scale is too short, making the model too certain about unexplored regions.

- Solution: Review and adjust the kernel's hyperparameters. For catalyst spaces, which can be high-dimensional, consider using Automatic Relevance Determination (ARD) kernels or more flexible surrogate models like Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART) that can better handle complex landscapes [7].

- Cause 1: The acquisition function (e.g., Probability of Improvement) is too greedy.

Problem: Model predictions are inaccurate and do not reflect my experimental results This indicates a poor fit of the surrogate model to your data.

- Potential Causes & Solutions

- Cause 1: The initial dataset is too small or does not cover the search space well.

- Solution: Increase the number of initial points sampled using a space-filling design like Sobol sequences to build a better initial model [5].

- Cause 2: The objective function has non-smooth patterns or discontinuities that a standard Gaussian Process with a common kernel (e.g., RBF) cannot capture.

- Solution: Use more adaptive surrogate models like BART or Bayesian Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (BMARS), which are designed to handle non-smooth functions and can perform automatic feature selection [7].

- Cause 1: The initial dataset is too small or does not cover the search space well.

Problem: The optimization loop is taking too long between iterations The computational overhead of the BO process itself becomes a bottleneck.

- Potential Causes & Solutions

- Cause 1: Maximizing the acquisition function is computationally expensive.

- Solution: Instead of a fine-grained discretization, use a numerical optimizer (e.g., L-BFGS-B) to find the acquisition function's maximum. You can also use a multi-start strategy to avoid local optima in this inner loop [1].

- Cause 2: The Gaussian Process surrogate is scaling poorly as the dataset grows.

- Cause 1: Maximizing the acquisition function is computationally expensive.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standard Protocol for a Bayesian Optimization Run

This protocol outlines the core steps for a single BO run, applicable to various domains including catalyst composition optimization [3] [5].

Define the Objective Function:

- Formally define your goal, for example:

x* = argmax f(x), wherexis a set of parameters (e.g., catalyst molar fractions) andf(x)is the expensive-to-evaluate function (e.g., catalytic current density) [3]. - Ensure the objective function can handle the input parameters and return a scalar value, even if the underlying process involves complex simulations or physical experiments.

- Formally define your goal, for example:

Specify the Feasible Search Space:

- Define the bounds for each parameter. For a quinary catalyst

Ag-Ir-Pd-Pt-Ru, the search space is a 4-simplex where the molar fractions sum to 1 [4].

- Define the bounds for each parameter. For a quinary catalyst

Select an Initial Design:

- Sample a small number of initial points (e.g., 5-20) from the search space to build the initial surrogate model.

- Use a space-filling technique like Sobol sequences to ensure good initial coverage [5].

Choose and Configure the Surrogate Model:

- Standard Choice: A Gaussian Process (GP) with a constant mean function and a squared exponential (RBF) kernel is a common and effective starting point [4].

- Kernel Hyperparameters: The kernel

k(x_i, x_j) = C² exp( -|x_i - x_j|² / 2l² )has amplitude (C) and length scale (l) parameters that are typically optimized based on the data [4].

Select an Acquisition Function:

- Recommended Default: The Expected Improvement (EI) function is a robust choice for most problems [4].

Execute the Sequential Optimization Loop:

- Iterate until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., budget exhausted, performance converged):

a. Fit/Update the Surrogate Model: Using all available data

D_{1:t-1}, update the posterior distribution of the surrogate model [3]. b. Maximize the Acquisition Function: Find the next pointx_tthat maximizes the acquisition functionα(x)[3]. c. Evaluate the Objective Function: Query the expensive objective function atx_tto obtainy_t = f(x_t)(potentially with noise) [8]. d. Augment the Dataset: Add the new observation(x_t, y_t)to the datasetD_{1:t} = {D_{1:t-1}, (x_t, y_t)}[8].

- Iterate until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., budget exhausted, performance converged):

a. Fit/Update the Surrogate Model: Using all available data

Quantitative Data for Experimental Design

The following table summarizes key metrics and parameters from a successful application of BO to catalyst design, providing a benchmark for your own experiments.

| Parameter / Metric | Value / Example | Context & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Sample Size | 2 compositions [4] | Used to initialize the GP surrogate model for a quinary HEA catalyst system. |

| Total Iterations (Budget) | 150 [4] | Sufficient to discover locally optimal compositions in the HEA case study. |

| Kernel Function | Squared Exponential (RBF) [4] | k(x_i, x_j) = C² exp( -|x_i - x_j|² / 2l² ); a standard choice for smooth functions. |

| Acquisition Function | Expected Improvement (EI) [4] | Balances exploration and exploitation by measuring the average expected improvement over the current best. |

| Stopping Criteria | Exhaustion of budget (e.g., 50-150 evaluations) [4] | A practical constraint for expensive experiments or simulations. |

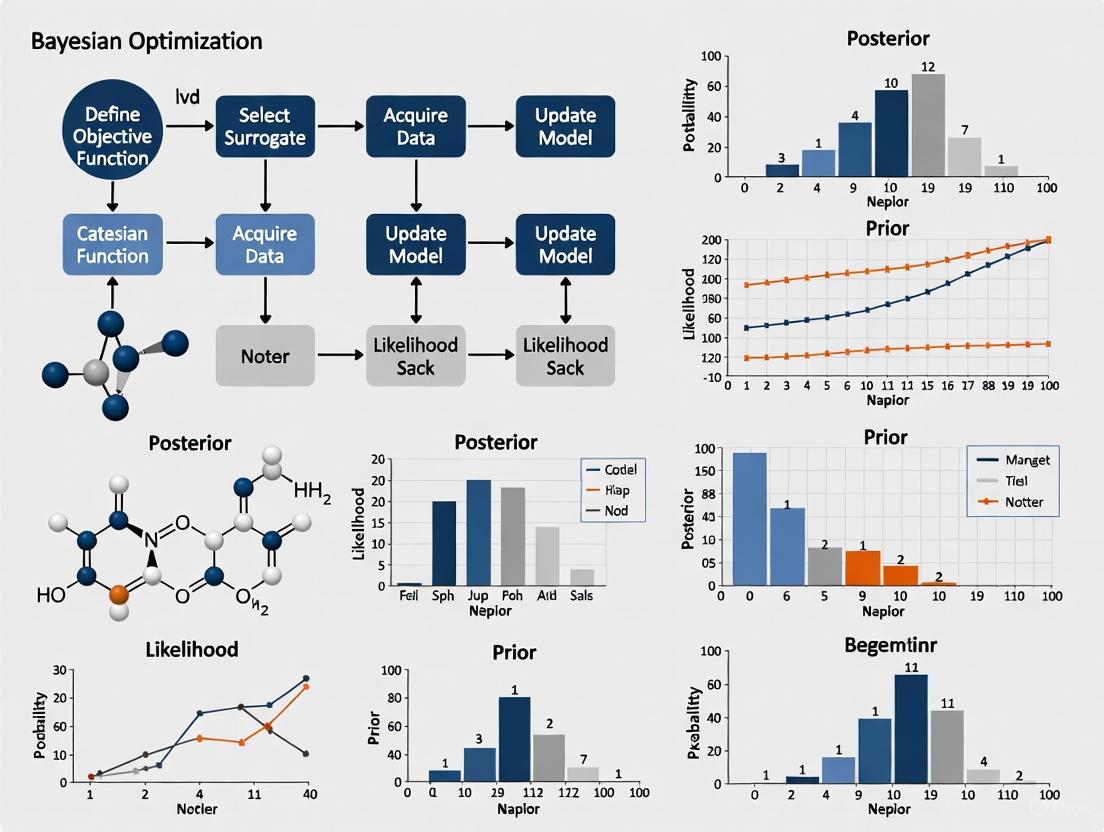

Workflow Visualization

BO Sequential Workflow

Troubleshooting Logic Map

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational and software "reagents" essential for implementing Bayesian Optimization in an experimental research setting.

| Tool / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | Serves as the probabilistic surrogate model; approximates the objective function and quantifies prediction uncertainty [5]. | The default choice for most BO applications; provides well-calibrated uncertainty estimates. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | An acquisition function that selects the next point to evaluate based on the expected value of improvement over the current best [3] [4]. | A robust, general-purpose choice for balancing exploration and exploitation. |

| Squared Exponential Kernel | A common kernel for GPs that assumes the objective function is smooth [4]. | k(x_i, x_j) = C² exp( -|x_i - x_j|² / 2l² ); a good starting point. |

| Bayesian Optimization Library (e.g., Botorch, Scikit-optimize) | Software packages that provide implemented BO loops, surrogate models, and acquisition functions [9] [6]. | Drastically reduces implementation time; essential for applying BO to real-world problems. |

| Space-Filling Design (e.g., Sobol Sequence) | A method for selecting initial evaluation points that maximize coverage of the search space [5]. | Critical for building an informative initial surrogate model before sequential design begins. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core components of a Bayesian Optimization (BO) framework? Bayesian Optimization is a powerful strategy for optimizing expensive black-box functions. Its core components are [10] [11]:

- Surrogate Model: A probabilistic model that approximates the unknown objective function. It is updated after each new evaluation.

- Acquisition Function: A function that uses the surrogate's predictions to decide the next point to evaluate by balancing exploration and exploitation. The typical BO workflow iterates through the following steps, as illustrated in the diagram below [11]:

Q2: My BO algorithm converges to a local optimum instead of the global one. How can I encourage more exploration? This is a classic sign of an over-exploitative strategy. You can address it by [10] [11]:

- Adjusting Your Acquisition Function: Switch to or tune the parameters of more explorative acquisition functions. For example, in the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) function, (a(x;\lambda) = \mu(x) + \lambda \sigma (x)), increase the (\lambda) parameter to give more weight to the uncertainty term (\sigma(x)) [10].

- Using Adaptive Trade-Off Methods: Recent research proposes acquisition functions that dynamically balance exploration and exploitation, which can prevent getting stuck in local optima better than fixed schedules [12].

- Consider a More Flexible Surrogate Model: Standard Gaussian Process (GP) surrogates with stationary kernels assume a uniform smoothness of the function. If your catalyst search space is complex or high-dimensional, non-stationary or more flexible models like Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART) may capture the underlying function better and guide the search more effectively [7].

Q3: How do I choose the right surrogate model for my catalyst optimization problem? The choice depends on the characteristics of your design space and the objective function. The table below compares common surrogate models:

| Surrogate Model | Key Features | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | Provides uncertainty estimates; mathematically explicit [7]. | Low-dimensional, smooth functions [7]. | Performance can degrade in high dimensions or with non-smooth functions [7]. |

| GP with ARD | Automatic Relevance Detection; assigns different length scales to each input variable [7]. | Problems where only a subset of variables is important [7]. | Can help with moderate dimensionality but still assumes smoothness [7]. |

| Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART) | Non-parametric; ensemble of small trees; handles complex interactions [7]. | High-dimensional spaces, non-smooth, or non-stationary functions [7]. | Often more robust and flexible than GP for complex spaces [7]. |

| Bayesian MARS | Uses product spline basis functions; non-parametric [7]. | Non-smooth functions with sudden transitions [7]. | Offers flexibility similar to BART [7]. |

| LLM with In-Context Learning | Uses natural language prompts; no feature engineering needed [13]. | Problems where materials can be naturally described in text (e.g., synthesis procedures) [13]. | A novel approach; performance may vary based on the LLM and prompting strategy [13]. |

Q4: What is the difference between Probability of Improvement (PI) and Expected Improvement (EI)? Both are popular acquisition functions, but they quantify "improvement" differently [10]:

- Probability of Improvement (PI): Measures the probability that a new point (x) will be better than the current best (f(x^+)). It only considers the likelihood of an improvement, not its magnitude. This can lead to over-exploitation, as it will favor points with even a tiny, almost certain improvement over points with a chance for a large but less certain gain [10].

- Expected Improvement (EI): Measures the expected value of the improvement. It considers both the probability of improvement and the potential magnitude of that improvement. This makes it less greedy than PI and generally a more balanced and effective choice [10] [11]. The analytical expression for EI under a GP surrogate is: [ \text{EI}(x) = \begin{cases} (\mu(\mathbf{x}) - f(\mathbf{x}^+) - \xi)\Phi(Z) + \sigma(\mathbf{x})\phi(Z) &\text{if}\ \sigma(\mathbf{x}) > 0 \ 0 & \text{if}\ \sigma(\mathbf{x}) = 0 \end{cases} ] where (Z = \frac{\mu(\mathbf{x}) - f(\mathbf{x}^+) - \xi}{\sigma(\mathbf{x})}) [11].

Q5: How can I implement a simple version of Expected Improvement (EI) in code? Here is a Python implementation of the EI acquisition function using a Gaussian Process surrogate model, as demonstrated in a practical tutorial [11].

Code source: Adapted from [11]

Q6: Are there quantitative measures to analyze the exploration behavior of my BO algorithm? Yes. Traditionally, analyzing exploration was qualitative. However, recent research has introduced quantitative measures, such as [14]:

- Observation Traveling Salesman Distance: Measures the spread of selected evaluation points by calculating the length of the shortest path connecting them all. A higher value indicates a more explorative strategy that samples from diverse areas.

- Observation Entropy: Quantifies the disorder or diversity in the distribution of selected points. Higher entropy also suggests greater exploration. These measures allow you to compare different acquisition functions objectively and diagnose if your algorithm is exploring the design space sufficiently [14].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Slow or No Convergence | - Over-exploitation (e.g., PI with low noise) [10].- Poorly chosen surrogate model kernel [7].- Data sparsity in high-dimensional space [7]. | - Use EI or UCB with a higher (\xi) or (\lambda) [10] [11].- Use a more flexible kernel or surrogate like BART[citati1].- Use ARD to identify irrelevant variables [7]. |

| Algorithm is Too Noisy/Sensitive | - Objective function is stochastic.- Acquisition function is too explorative. | - Use a GP that explicitly models noise (e.g., via alpha parameter) [11].- Use a Monte Carlo acquisition function that handles noise [15].- Reduce the (\lambda) parameter in UCB [10]. |

| Optimization Takes Too Long per Iteration | - Surrogate model is expensive to train with many data points.- Inner optimization of the acquisition function is slow. | - Use a surrogate with faster training times (e.g., BART for large datasets).- Use a quasi-second order optimizer like L-BFGS-B with a fixed set of base samples for MC acquisition functions [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Catalyst Composition with BO

This protocol outlines the steps for using Bayesian Optimization to find an optimal catalyst composition, based on methodologies successfully applied in materials science [7] [13].

1. Problem Formulation:

- Objective Function ((f(x))): Define the property to maximize/minimize (e.g., catalytic yield, selectivity). This is your expensive "black-box" experiment.

- Design Space ((\Omega)): Define the bounds of your variables (e.g., concentrations of metals, synthesis temperature, pressure).

2. Initial Experimental Design:

- Generate an initial set of points to first evaluate. A common method is Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to ensure the space is covered space-fillingly [16].

- A typical initial size can be 5-20 points, depending on the dimensionality and expected complexity of your space [7].

3. Iterative Bayesian Optimization Loop: The core loop follows the Ask-Tell paradigm, which is well-suited for managing sequential experiments [13]. The following diagram illustrates this workflow in the context of catalyst optimization:

Workflow adapted from the BO-ICL approach for catalyst discovery [13]

- Step 1 - Fit Surrogate Model: Train your chosen surrogate model (e.g., GP, BART) on all data collected so far [7] [16].

- Step 2 - Propose Next Experiment: Optimize the acquisition function (e.g., EI) over the design space to find the point (x) that is most promising to evaluate next [11].

- Step 3 - Run Experiment: Synthesize and test the catalyst composition at the proposed point (x), measuring the outcome (y = f(x)).

- Step 4 - Update Data: Augment the dataset with the new observation ((x, y)).

- Repeat steps 1-4 until the evaluation budget is exhausted or performance converges.

4. Validation:

- Validate the final recommended catalyst composition with repeated experiments to ensure reliability.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key computational tools and models used in advanced Bayesian Optimization research, particularly relevant for catalyst design.

| Tool / Model | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| BoTorch | Library (Python) | A flexible framework for Bayesian Optimization research and deployment, providing state-of-the-art Monte Carlo and analytic acquisition functions [15]. |

| GPT Models (e.g., GPT-3.5) | Large Language Model | Acts as a surrogate model using In-Context Learning (ICL), allowing optimization directly on text-based descriptions of materials and synthesis procedures [13]. |

| Bayesian Optimization with Adaptive Surrogates | Algorithmic Framework | Uses flexible surrogate models (BMARS, BART) to overcome limitations of standard GPs in high-dimensional or non-smooth problems [7]. |

| Ask-Tell Interface | Programming Interface | A conceptual API that clearly separates the step of asking for a new candidate point ("Ask") from telling the model the result ("Tell"), simplifying the management of the optimization loop [13]. |

Why Catalyst Composition Optimization is an Ideal 'Black-Box' Problem for BO

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What makes catalyst composition optimization a "black-box" problem? In catalyst development, the relationship between a catalyst's composition and its performance (e.g., activity or selectivity) is typically a black-box function. This means you can input a composition and measure the output performance, but the precise internal relationship or "formula" is unknown, complex, and difficult to model from first principles. Evaluating this function is also expensive and time-consuming, as it requires synthesizing the catalyst and running experiments [17] [18]. Bayesian Optimization (BO) is designed specifically for such scenarios, where you can only query a costly black-box function and need to find its optimum efficiently [19].

2. My BO algorithm seems to get stuck in a local optimum. How can I encourage more exploration? This is a classic exploration-exploitation trade-off issue. You can address it by switching your acquisition function. The Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) function has a tunable parameter (β) that explicitly controls this balance; a higher β value encourages more exploration of uncertain regions [17]. Alternatively, Expected Improvement (EI) naturally balances improvement over the current best value with uncertainty, which can help avoid getting stuck [17] [19]. If these don't suffice, consider more advanced methods like Reinforcement Learning (RL)-based BO, which uses multi-step lookahead to make less myopic decisions and has shown better performance in navigating complex, high-dimensional landscapes [18] [20].

3. How can I incorporate practical experimental constraints into the BO process?

You can handle black-box constraints by using a joint acquisition function. A common approach is to combine Expected Improvement (EI) for the objective (e.g., catalytic yield) with the Probability of Feasibility (PoF) for the constraint. The overall acquisition function to maximize becomes EI(x) * PoF(x). This ensures that the algorithm selects points that are likely to be high-performing and adhere to your experimental constraints [21].

4. I have a large pool of potential catalyst candidates. How can a frozen LLM help with optimization? Recent research introduces BO with In-Context Learning (BO-ICL), which uses a frozen Large Language Model (LLM) as the surrogate model. The catalyst compositions and experimental procedures are represented as natural language prompts. The LLM, leveraging its in-context learning ability, predicts the performance and uncertainty for new compositions. This "AskTell" algorithm updates the model's knowledge through dynamic prompting without retraining, making it highly efficient. This method has successfully identified near-optimal multi-metallic catalysts for the reverse water-gas shift (RWGS) reaction from a pool of 3,700 candidates in only six iterations [13].

5. When should I consider moving from standard BO to a more advanced method like RL-BO? Consider this transition when dealing with high-dimensional problems (e.g., D ≥ 6) or when you suspect that the single-step (myopic) nature of standard acquisition functions like EI is limiting performance. Reinforcement Learning-based BO (RL-BO) formulates the optimization as a multi-step decision process, which can be more effective in complex design spaces. A hybrid strategy is often beneficial: use standard BO for efficient early-stage exploration and then switch to RL-BO for refined, adaptive learning in later stages [20].

Experimental Protocols & Case Studies

The following table summarizes key experimental cases where Bayesian Optimization has been successfully applied to catalyst composition optimization.

| Catalyst System / Reaction | Key Optimization Variables | BO Approach & Surrogate Model | Key Outcome / Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoO Nanoparticles for CO₂ Hydrogenation [22] | Colloidal synthesis parameters (e.g., precursors, ligands, temperature, time) to control crystal phase & morphology. | Multivariate BO with a data-driven classifier. | Identified conditions for phase-pure rock salt CoO nanoparticles that were small and uniform. The optimized catalyst showed higher activity and ~98% CH₄ selectivity across various pretreatment temperatures. |

| Multi-metallic catalysts for Reverse Water-Gas Shift (RWGS) [13] | Composition of multi-metallic catalysts from a large candidate pool. | BO with In-Context Learning (BO-ICL) using a frozen LLM (GPT-3.5, Gemini) as a surrogate model with natural language prompts. | Found a near-optimal catalyst within 6 iterations from a pool of 3,700 candidates, achieving performance close to thermodynamic equilibrium. |

| Ag/C catalysts for electrochemical CO₂ reduction [18] | Synthesis conditions for Ag/C composite catalysts. | Reinforcement Learning-based BO (RL-BO) using a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model within an RL framework for multi-step lookahead. | The RL-BO approach demonstrated more efficient optimization compared to traditional PI and EI-based BO methods. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Components for BO in Catalysis Research

| Tool / Component | Function in the BO Workflow | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | A probabilistic model used as a surrogate to approximate the expensive black-box function. It provides a mean prediction and, crucially, an uncertainty estimate for any point in the search space [17] [23]. | The default choice for many BO applications due to its uncertainty quantification. Kernels like Matérn 5/2 are often preferred [20] [23]. |

| Acquisition Function | Guides the search by determining the next point to evaluate. It uses the GP's predictions to balance exploration (high uncertainty) and exploitation (high mean prediction) [17] [19]. | Expected Improvement (EI) and Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) are among the most common [17] [20]. |

| Large Language Model (LLM) Surrogate | An alternative surrogate model that operates on natural language representations of experiments, enabling optimization without manual feature engineering [13]. | Used in BO-ICL; models like GPT-3.5 or Gemini can be used in a frozen state, updated via in-context learning (prompting) rather than retraining [13]. |

| Probability of Feasibility (PoF) | A specific type of acquisition function used to handle black-box constraints. It estimates the likelihood that a candidate point will satisfy all experimental constraints [21]. | Often multiplied with EI (e.g., EI * PoF) to find points that are high-performing and feasible [21]. |

Workflow Visualization: Bayesian Optimization for Catalyst Design

The following diagram illustrates the iterative feedback loop that is central to the Bayesian Optimization process.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the fundamental limitations of the traditional "One Factor at a Time" (OFAT) approach that DOE overcomes?

The traditional OFAT method, which involves changing one variable while holding all others constant, has several key disadvantages compared to a structured Design of Experiments (DOE) approach. OFAT provides limited coverage of the experimental space and, most critically, fails to identify interactions between different factors [24]. This means you might miss the optimal solution for your catalyst formulation. Furthermore, OFAT is an inefficient use of resources like time, materials, and reagents [24] [25]. DOE, by contrast, systematically studies multiple factors and their interactions simultaneously, leading to a more thorough and efficient path to optimization.

FAQ 2: How does AI-guided DOE represent an advancement over traditional DOE methods?

AI-guided DOE is a powerful upgrade that integrates sophisticated AI algorithms with traditional DOE techniques. Think of it as replacing a compass with a cutting-edge GPS system [26]. Key advantages include:

- Automated Experiment Design: AI intelligently selects the most critical factors to test, streamlining the process [26].

- Predictive Analytics: It leverages historical data to predict potential outcomes, allowing for more proactive experimental planning [26].

- Real-time Analysis: AI can analyze data as it is generated, enabling on-the-fly adjustments to refine experiments and enhance precision [26].

- Reduced Expertise Dependency: By automating complex statistical tasks, AI-guided DOE makes powerful experimentation more accessible to a broader range of researchers [26].

FAQ 3: What are the common pitfalls in experimental design that can undermine results, especially in a high-throughput setting?

Even with advanced tools, several common pitfalls can compromise experimental outcomes [27]:

- Inadequate Design: This includes running experiments without a clear hypothesis, lacking a proper control group, or using an insufficient sample size, which can lead to unreliable results.

- Data Quality Issues: Poor data collection methods, a lack of data validation, and improper handling of outliers can introduce bias and errors.

- Statistical Missteps: Peeking at interim results without statistical correction, misusing statistical tests, and failing to account for the "multiple comparisons problem" can inflate false positives and lead to invalid conclusions.

- Organizational Challenges: A lack of leadership buy-in, biased assumptions that lead teams to ignore surprising data, and poor cross-team collaboration can all hinder successful experimentation programs [27].

FAQ 4: How can Bayesian Optimization be integrated with HTE and DOE for catalyst discovery?

Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a powerful strategy for navigating vast design spaces, such as multi-metallic catalyst compositions. It works by using a surrogate model to approximate the objective function (e.g., catalytic activity) and an acquisition function to intelligently select the next most promising experiment [13]. This can be directly integrated with HTE and DOE. A novel approach involves using large language models (LLMs) as the surrogate model through in-context learning, a method known as BO-ICL. This allows researchers to represent catalyst synthesis and testing procedures as natural language prompts. The BO-ICL workflow can then identify high-performing catalysts from a pool of thousands of candidates in a very small number of iterative cycles, dramatically accelerating discovery [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Experiment Results are Noisy or Inconclusive

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Sample Size or Replication [27] | Calculate the statistical power of your experimental design. | Increase the number of experimental replicates to ensure results are reliable and not due to random chance [27] [28]. |

| Uncontrolled Confounding Variables [27] | Review your experimental setup for environmental factors (e.g., temperature fluctuations, reagent lot variations) that were not accounted for. | Implement tighter process controls and use randomization during experimental runs to minimize the influence of lurking variables [25] [28]. |

| Poor Data Collection Methods [27] | Audit data entry and instrument calibration logs for inconsistencies. | Establish reliable, standardized data collection protocols and implement automated data capture where possible to reduce human error [27]. |

Issue 2: Failure to Find an Optimal Catalyst Composition

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| OFAT Approach Limiting Discovery | Analyze your experimental history to see if factors have only been varied in isolation. | Shift from an OFAT to a fractional factorial or response surface methodology (RSM) design. This will efficiently screen many factors and reveal critical interaction effects [25]. |

| Vast, Complex Design Space | Assess the number of potential element combinations and reaction conditions; it may be too large to explore exhaustively. | Integrate AI-guided DOE and Bayesian Optimization [26] [13]. These methods use predictive models to focus experimental efforts on the most promising regions of the design space. |

| Ignoring Factor Interactions | Check the analysis from your last DOE for significant interaction terms in the statistical model. | Ensure your DOE is designed to capture two-factor interactions. Use statistical software to analyze results and visualize interaction plots to understand synergistic effects [25]. |

Issue 3: Barriers to Implementing HTE and DOE in the Lab

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Complexity of Statistics [29] | Gauge the team's comfort level with statistical concepts like ANOVA and factorial designs. | Utilize modern DOE software that simplifies the design and analysis process. Foster collaboration between domain experts (biologists, chemists) and data specialists [29]. |

| Difficulty in Executing Complex Experiments [29] | Evaluate the time and error rate associated with manually preparing experimental arrays. | Invest in laboratory automation solutions, such as automated liquid and powder dispensing robots (e.g., CHRONECT XPR), to execute complex designs accurately and efficiently [29] [30]. |

| Challenges in Data Modeling [29] | Determine if the team has the tools and skills to model and interpret multi-dimensional data. | Leverage data analysis software with built-in modeling and visualization capabilities (contour plots, 3D surfaces). Collaborate with bioinformaticians or statisticians for advanced analysis [29]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Setting Up a High-Throughput Catalyst Screening Campaign

This protocol outlines the steps for using an automated HTE platform to screen catalyst compositions for a reaction like the reverse water-gas shift (RWGS) [30] [13].

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| CHRONECT XPR Automated Powder Dosing System | Precisely dispenses solid catalysts, precursors, and inorganic additives at milligram scales into multi-well arrays [30]. |

| 96-Well Array Manifolds | Serves as the reaction vessel for parallel synthesis and testing at miniaturized scales [30]. |

| Automated Liquid Handling System | Dispenses solvents, corrosive liquids, and other liquid reagents accurately and reproducibly [30]. |

| Inert Atmosphere Glovebox | Provides a controlled environment for handling air-sensitive catalysts and reagents [30]. |

2. Methodology

- Step 1: Experimental Design. Define the objective (e.g., maximize CO yield). Select factors (e.g., metal ratios, dopants, reaction temperature) and their levels. Use a DOE screening design (e.g., Plackett-Burman or fractional factorial) to select the set of catalyst compositions to test.

- Step 2: Automated Solid Dispensing. Program the CHRONECT XPR system with the experimental design. The robot will automatically dose a wide range of solids into designated vials in the 96-well array. Reported deviations can be <10% at sub-mg scales and <1% at >50 mg scales [30].

- Step 3: Liquid Reagent Addition. Using an automated liquid handler, add the required solvents and liquid precursors to the solid catalysts in the array.

- Step 4: Parallel Reaction Execution. Place the 96-well array manifold into a controlled environment (heater/chiller) to initiate and run the reactions in parallel.

- Step 5: Automated Analysis & Data Collection. Use integrated analytical equipment (e.g., GC-MS, HPLC) to sample and analyze the reaction outcomes from each well, compiling data into a centralized database.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Bayesian Optimization Loop for Catalyst Optimization

This protocol describes how to use Bayesian Optimization to iteratively guide catalyst discovery campaigns [13].

1. Methodology

- Step 1: Create an Unlabeled Candidate Pool. Generate a large library (e.g., 3,700 candidates) of potential catalyst compositions and synthesis procedures, representing them in a structured natural language format (e.g., "5% Cu on ZrO2 support, calcined at 500°C") [13].

- Step 2: Initialize with a Small DOE. Select a small, diverse set of candidates from the pool (e.g., 10-20) using a space-filling DOE. Synthesize and test these candidates to collect the initial dataset of composition-performance pairs.

- Step 3: Build a Surrogate Model. Train a machine learning model (e.g., Gaussian Process, Random Forest, or an LLM via in-context learning as in BO-ICL) on the accumulated data. This model predicts the performance of any candidate in the pool and estimates the uncertainty of its prediction [13].

- Step 4: Propose the Next Experiment. Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement), which balances exploration (high uncertainty) and exploitation (high predicted performance), to select the single most promising candidate from the pool for the next experiment [13].

- Step 5: Run the Experiment and Update. Synthesize and test the proposed candidate, then add the new data point to the training set. Repeat from Step 3 until a performance target is met or the experimental budget is exhausted. This workflow has been shown to identify near-optimal catalysts in as few as six iterations [13].

Workflow Visualization

HTE and BO Integrated Workflow

AI-Guided vs. Traditional DOE

Advanced BO Methodologies and Real-World Catalyst Applications

Gaussian Processes as the Standard Surrogate Model for Catalytic Property Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a Gaussian Process (GP) the preferred surrogate model in Bayesian optimization (BO) for catalyst design?

GPs are the standard choice in BO for several key reasons. They provide a probabilistic framework that delivers not just a predicted value for catalytic properties (e.g., yield, selectivity) but also a quantifiable uncertainty (variance) at any point in the design space [13] [31]. This uncertainty estimate is crucial for the acquisition function in BO to effectively balance exploration (testing in uncertain regions) and exploitation (testing near predicted optima) [32] [33]. Furthermore, GPs are non-parametric and make minimal assumptions about the underlying functional form of the catalyst property landscape, allowing them to model complex, non-linear relationships from limited data, a common scenario in experimental catalysis [33] [31].

Q2: My GP model is overfitting to my small dataset of catalyst experiments. What can I do?

Overfitting, where the model fits the noise in the training data rather than the underlying trend, is often signaled by a trained GP that shows wild oscillations between data points. This is frequently controlled by the length-scale hyperparameter in the covariance function [34].

- A shorter length-scale allows the function to have faster variations, leading to overfitting.

- A longer length-scale results in a "stiffer" function that is less flexible and can underfit [34]. Solution: Instead of manually setting the length-scale, use automatic hyperparameter optimization. Most modern GP implementations will automatically tune these hyperparameters (like length-scale and signal variance) by maximizing the marginal likelihood of the data. This process finds the best model that explains your data without being overly complex [34] [35].

Q3: For catalyst optimization, should I use a single-objective or multi-objective GP?

Most real-world catalyst design involves multiple, often conflicting, objectives (e.g., high yield, high selectivity, low cost). While single-objective BO is simpler, a multi-objective approach is often necessary [32].

- Standard Practice: Conventional multi-objective BO models each property with an independent GP [32].

- Advanced Recommendation: For correlated properties (e.g., the common strength-ductility trade-off in materials), use Multi-Task Gaussian Processes (MTGPs) or Deep Gaussian Processes (DGPs). These advanced models explicitly learn correlations between different material properties, allowing them to share information across tasks. This leads to more efficient exploration and can significantly accelerate the discovery of catalysts that balance multiple performance criteria [32].

Q4: How do I represent a catalyst as an input for a Gaussian Process model?

The choice of catalyst representation, or descriptors, is critical for model performance. Successful approaches in the literature include:

- Physicochemical Descriptors: Using calculated quantum chemical descriptors, such as highest occupied molecular orbital energy (EHOMO) or steric parameters like percent buried volume (%Vbur), which provide mechanistically meaningful information [33].

- Fragmentation Strategy: For complex catalyst ligands, dividing the molecule into fragments and calculating descriptors for each part can be effective, especially with small datasets [33].

- Natural Language Representations: Recently, representing catalyst synthesis procedures and structures in natural language has emerged as a powerful, task-agnostic method, enabling the use of large language models as surrogates without extensive feature engineering [13].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Poor Model Performance with Small Datasets

Problem: The GP surrogate model provides inaccurate predictions and poor guidance for the next experiments, often due to a very limited initial dataset of catalyst tests.

Solution: Implement an active learning loop where the BO algorithm itself guides data collection.

- Procedure:

- Start with a small initial dataset (e.g., 10-20 catalyst experiments chosen via Latin Hypercube or Sobol sequence).

- Train the GP model on this data.

- Use the acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) to select the catalyst or reaction condition predicted to be most optimal or informative.

- Run the experiment and add the new data point to the training set.

- Re-train the GP model and repeat.

- Case Study: In optimizing stereoselective polymerization catalysts, this method converged to high-performance catalysts within 7 iterations, drastically outperforming random search [33].

Handling Multiple Correlated Objectives

Problem: You need to optimize multiple catalytic properties simultaneously and suspect they are correlated, but using independent GPs is inefficient.

Solution: Employ Multi-Task or Hierarchical Gaussian Processes.

- Procedure:

- Identify the primary objectives (e.g., catalytic activity and selectivity).

- Choose an MTGP or DGP model architecture capable of modeling the covariance between different tasks or properties.

- Train the model on your dataset where all properties are measured for each catalyst candidate.

- The model will leverage correlations; for example, if two properties are positively correlated, an improvement in one suggests a likely improvement in the other, guiding the search more effectively [32].

- Evidence: Research on high-entropy alloys demonstrated that a hierarchical DGP (hDGP-BO) was the most robust and efficient method for discovering materials with optimal combinations of properties like low thermal expansion and high bulk modulus [32].

Numerical Instabilities during Model Training

Problem: The GP training process fails due to an ill-conditioned or non-invertible covariance matrix.

Solution: This is often caused by duplicate data points or numerically singular matrices.

- Procedure:

- Add Jitter: Introduce a small positive value (e.g., 10^−6) to the diagonal of the covariance matrix. This is a standard technique to ensure numerical stability and is equivalent to assuming a tiny amount of independent Gaussian noise in the observation process [31].

- Remove Duplicates: Ensure your training data does not contain duplicate input points.

- Standardize Data: Standardize both your input parameters (e.g., center and scale catalyst descriptors) and output responses. This improves the conditioning of the covariance matrix and helps hyperparameter optimization converge more reliably [35].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Setting up a GP Surrogate for Catalyst Yield Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps to create a GP surrogate model for predicting catalytic yield based on catalyst composition and reaction condition descriptors.

Objective: To build a predictive model that maps catalyst descriptors to catalytic yield for use in a Bayesian optimization loop.

Materials and Software:

- A dataset of catalyst experiments with defined input descriptors and measured output (yield).

- GP software (e.g., scikit-learn in Python, MOOSE Framework, COMSOL).

Steps:

- Data Preparation:

- Inputs: Compile descriptors for each catalyst experiment (e.g., physicochemical properties, fragment descriptors, or linguistic representations).

- Output: Compile the corresponding catalytic performance metric (e.g., yield, conversion, selectivity).

- Preprocessing: Standardize all input descriptors and the output response to have zero mean and unit variance.

Model Configuration:

- Covariance Function: Select a kernel. The Squared Exponential (Radial Basis Function) kernel is a common and robust starting point [34] [35].

- Hyperparameters: Define initial values for hyperparameters (length scales, signal variance). For the Squared Exponential kernel, this includes

length_factorandsignal_variance[35]. - Optimization: Configure the trainer to automatically optimize (tune) all hyperparameters by maximizing the log marginal likelihood [35].

Model Training & Evaluation:

- Training: Train the GP model on the prepared dataset.

- Validation: Use hold-out validation or cross-validation to assess prediction error (e.g., RMSE, MAE).

- Uncertainty: Ensure the model provides uncertainty estimates (standard deviation) for its predictions, which are critical for the BO acquisition function.

Protocol: Running a Single Iteration of Bayesian Optimization

This protocol describes one cycle of the BO loop for catalyst discovery.

Objective: To use the GP surrogate to select the most promising catalyst candidate for the next experiment.

Steps:

- Update Surrogate: Train the GP surrogate model on all available data (historical data + data from previous BO iterations).

- Optimize Acquisition: Using the trained GP, calculate the acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) across the unexplored candidate space.

- Select Next Experiment: Identify the candidate catalyst (point in the design space) that maximizes the acquisition function.

- Run Experiment: Synthesize and test the selected catalyst, recording its performance.

- Augment Dataset: Add the new input-output pair to the existing dataset [33] [13].

Workflow Diagram

The diagram below illustrates the iterative Bayesian optimization workflow for catalyst design, with the Gaussian Process surrogate model at its core.

Research Reagent & Computational Solutions

The table below summarizes key computational "reagents" – descriptors, models, and software – essential for building GP surrogates in catalyst optimization.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GP-Based Catalyst Optimization

| Category | Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Descriptors | DFT-calculated Descriptors (e.g., EHOMO, %Vbur) [33] | Provide mechanistically meaningful features for the GP model; crucial for building interpretable structure-activity relationships. |

| Fragmentation-Based Descriptors [33] | Represent complex catalyst ligands by breaking them into smaller, computable fragments; useful for large combinatorial spaces. | |

| Natural Language Representations [13] | Represent catalysts and synthesis procedures as text, enabling the use of language models and avoiding manual feature engineering. | |

| GP Models & Kernels | Squared Exponential (RBF) Kernel [34] [35] | A default, general-purpose kernel that assumes smooth, infinitely differentiable functions. |

| Multi-Task Gaussian Process (MTGP) [32] | A surrogate model that learns correlations between multiple catalytic properties, improving data efficiency in multi-objective optimization. | |

| Software & Tools | Bayesian Optimization Libraries (e.g., BoTorch, Ax) | Provide pre-built frameworks for implementing GP surrogates and acquisition functions. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software (e.g., Gaussian) [33] | Used to calculate electronic and steric descriptors for catalyst candidates. | |

| Experimental Design | Sobol Sequence [36] | A quasi-random method for selecting an initial set of catalyst experiments that uniformly covers the parameter space. |

Leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs) and In-Context Learning for Language-Based Catalyst Representation

FAQs: Core Concepts

Q1: What is a "language-based catalyst representation" and why is it useful? A language-based catalyst representation describes a catalyst—its chemical composition, structure, synthesis method, and testing conditions—using natural language instead of numerical descriptors. For example, a catalyst might be described as "a bimetallic catalyst with a 1:3 Pd:Cu ratio, supported on ceria, synthesized via wet impregnation, and tested for the reverse water-gas shift reaction at 500°C" [13]. This approach is useful because it allows researchers to leverage the vast knowledge embedded in pre-trained Large Language Models (LLMs) without the need for complex, hand-crafted feature engineering. It provides a flexible and intuitive way to integrate diverse, multi-faceted experimental information into a single, optimizable format [13].

Q2: How does In-Context Learning (ICL) work with Bayesian Optimization (BO) for catalyst design? In this paradigm, ICL allows a frozen LLM to learn from a context of past experimental results provided directly in its prompt. The LLM acts as the surrogate model within a BO loop. The process, often called BO-ICL, follows these steps [13]:

- Ask: The LLM, prompted with a few previous (catalyst description, performance) examples, predicts the performance of new, candidate catalysts and estimates its uncertainty.

- Experiment: The top candidate, selected by an acquisition function that balances high performance and high uncertainty, is synthesized and tested.

- Tell: The new experimental result is added to the context of examples for the next LLM prompt. This "Ask-Tell" loop continually updates the LLM's context, enabling it to refine its predictions and guide the search towards high-performing catalysts without any retraining of the model weights [13].

Q3: My LLM's predictions for catalyst performance are inaccurate. What could be wrong? This common issue can stem from several parts of the experimental pipeline:

- Insufficient or Poor-Quality In-Context Examples: The LLM may not have enough relevant examples in its prompt to discern the underlying structure-property relationships. Ensure the in-context examples are high-quality and directly relevant to the search space [13].

- Improper Uncertainty Calibration: The accuracy of BO heavily relies on well-calibrated uncertainty estimates from the LLM. You may need to adjust the uncertainty scaling factor (a hyperparameter in BO-ICL) to balance exploration and exploitation effectively [13].

- Vague or Inconsistent Catalyst Descriptions: The language used to describe catalysts must be structured and consistent. Ambiguous descriptions lead to noisy representations and poor model performance. Implement a standardized template for describing catalysts [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The BO-ICL loop fails to explore and gets stuck in a local performance maximum.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Over-exploitation | Check the acquisition function history. Is it consistently selecting candidates with high predicted performance but low uncertainty? | Increase the uncertainty scaling factor in the acquisition function to encourage exploration of less certain regions [13]. |

| Uninformative Context | Analyze the diversity of catalysts in the in-context examples. Are they all chemically similar? | Manually add a catalyst from a different region of the design space to the prompt to "jump-start" exploration [37]. |

| LLM Temperature Setting | The model's temperature parameter is too low, making its outputs deterministic. | Slightly increase the temperature (e.g., from 0 to 0.3) to introduce stochasticity in the predictions, aiding exploration [13]. |

Problem: The LLM cannot parse or understand the natural language descriptions of catalysts.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Domain Tuning | The base LLM performs poorly on scientific terminology. | Use a domain-adapted LLM like CataLM, which is pre-trained on catalysis literature, for significantly improved comprehension [38]. |

| Poor Prompt Structure | The prompt is unstructured, making it hard for the LLM to distinguish between catalyst attributes. | Implement a structured prompt template with clear sections for composition, support, synthesis, and test conditions [13]. |

| Inconsistent Nomenclature | The same element or method is referred to by different names (e.g., "Pd" vs. "Palladium"). | Create a controlled vocabulary for catalyst descriptions to ensure consistency across all experiments [39]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Bayesian Optimization with In-Context Learning (BO-ICL) for Catalyst Discovery

This protocol outlines the steps for using BO-ICL to discover novel catalysts, as demonstrated for the reverse water-gas shift (RWGS) reaction [13].

- Create an Unlabeled Candidate Pool: Generate a virtual library of potential catalysts, each described in a structured natural language format. For example: "

[Metal A]_[Metal B]_[Support]_[Synthesis Method]" [13] [37]. - Initialize with Random Samples: Select a small number (e.g., 5-10) of catalysts from the pool at random, synthesize them, and measure their performance (e.g., CO₂ conversion or product yield).

- Construct the Initial Prompt: Format the results from step 2 as in-context examples for the LLM. The prompt should include: the system's task description, the few examples (catalyst description -> performance), and the query about a new candidate.

- Run the BO-ICL Loop: Iterate until a performance target or experimental budget is reached:

- Ask: The LLM processes the prompt to predict the performance and uncertainty for all candidates in the unlabeled pool.

- Select: An acquisition function (e.g., Upper Confidence Bound) uses these predictions to select the most promising candidate for the next experiment.

- Experiment: Synthesize and test the selected candidate to obtain its true performance value.

- Tell: Update the prompt by adding this new (catalyst, performance) pair to the in-context examples, and remove it from the candidate pool.

- Validation: Synthesize and test the top-performing catalyst identified by the BO-ICL process to confirm its performance.

Performance Benchmarks of BO-ICL

The following table summarizes quantitative results from applying BO-ICL to different chemical problems, demonstrating its sample efficiency [13].

| Dataset / Task | Key Performance Metric | BO-ICL Result | Benchmark Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Coupling of Methane (OCM) | Convergence to top 1% of catalysts | ~30 iterations | Matched or outperformed Gaussian Processes [13] |

| Aqueous Solubility (ESOL) | Regression Accuracy (RMSE) | Competitive performance | Comparable to Kernel Ridge Regression [13] |

| Reverse Water-Gas Shift (RWGS) | Discovery of near-optimal catalyst | 6 iterations | Identified high-performing multi-metallic catalyst from 3,700 candidates [13] |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the closed-loop, iterative process of optimizing catalysts using BO-ICL.

BO-ICL Catalyst Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational and experimental "reagents" essential for implementing the described BO-ICL framework for catalyst design.

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Pre-trained LLM (e.g., GPT-series, Gemini) | The core engine that processes language-based catalyst representations and performs regression with uncertainty estimation through ICL [13]. |

| Domain-Adapted LLM (e.g., CataLM) | A language model pre-trained on catalysis literature, offering superior comprehension of domain-specific terminology and relationships [38]. |

| Structured Prompt Template | A pre-defined format for describing catalysts and their performance, ensuring consistency and improving the LLM's ability to learn from context [13]. |

| Acquisition Function (e.g., UCB, EI) | A function that uses the LLM's prediction and uncertainty to balance exploration and exploitation, deciding the next catalyst to test [13] [37]. |

| Virtual Catalyst Library | A computationally generated list of possible catalyst compositions and structures, described in natural language, which serves as the search space for the BO-ICL algorithm [37]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Rig | An automated system for the rapid synthesis and testing of catalyst candidates selected by the BO-ICL loop, crucial for closing the feedback loop efficiently [37]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is Multi-Task Bayesian Optimization (MTBO) and how does it differ from standard Bayesian optimization?

Multi-Task Bayesian Optimization (MTBO) is an advanced machine learning framework that accelerates the optimization of a primary, often expensive-to-evaluate task by leveraging knowledge gained from related, auxiliary tasks. Unlike standard Bayesian optimization, which starts from scratch for every new problem, MTBO uses a multi-task probabilistic model (like a multi-task Gaussian Process) to learn correlations between different tasks. This allows it to make more informed decisions from the very beginning of the optimization campaign, significantly reducing the number of experiments needed to find optimal conditions. [40] [41]

FAQ 2: When should I consider using MTBO for my catalyst discovery project?

You should consider MTBO if your work involves:

- Optimizing a new catalytic reaction where you have historical data from similar reactions with different substrates. [40]

- Balancing data from different sources, such as combining high-throughput computational screening (density functional theory - DFT) with physical experiments. [42]

- Avoiding the "cold-start" problem when experimental resources for the primary task are extremely limited or expensive. [42]

- Working with a family of related catalysts, where you aim to find the best performer and its optimal conditions simultaneously. [43]

FAQ 3: How do I determine if my historical data is suitable for transfer learning with MTBO?

The suitability depends on the relatedness of the tasks. Your historical data is likely suitable if the auxiliary and primary tasks share underlying physical or chemical principles. For example, data from Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reactions with different aryl halides can often be leveraged to optimize a new Suzuki-Miyaura coupling. [40] The MTBO algorithm is designed to be robust; even with imperfectly related tasks, it can still function effectively, though the performance gains may be more modest. Benchmarking the performance of MTBO against single-task optimization on a small scale can help assess the value of your historical data. [40]

FAQ 4: What are the common computational bottlenecks when running MTBO, and how can I address them?

Common bottlenecks and their solutions include:

- Scalability with many tasks: Traditional multi-task Gaussian Processes can saturate in performance beyond a moderate number of tasks. Emerging solutions involve using Large Language Models (LLMs) to learn from thousands of past optimization trajectories or employing more scalable surrogate models like Random Forests. [44] [45]

- High-dimensional search spaces: The "curse of dimensionality" can make optimization slow. Dimensionality reduction or feature selection based on domain knowledge can help. Alternatively, platforms like Citrine Informatics use Random Forests that naturally handle high-dimensional, discontinuous spaces more efficiently. [45]

- Handling multiple objectives and constraints: Standard BO is single-objective. For multiple objectives (e.g., maximizing yield while minimizing cost), you need Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO), which adds complexity. Hard constraints can be incorporated by modeling the probability of constraint satisfaction. [45]

FAQ 5: My MTBO model is suggesting catalyst formulations that seem chemically impractical. What could be wrong?

This is a known limitation of treating optimization as a pure black-box problem. It can occur if:

- The model lacks domain knowledge and chemical constraints. The solution is to integrate known chemical rules (e.g., stability conditions, compatibility) directly into the search space or the model itself to filter out invalid suggestions. [45]

- The kernel or surrogate model fails to capture the complex, non-linear relationships in your chemical space. Using models that offer better interpretability, like Random Forests, can help you understand which features are driving the suggestions and identify unphysical correlations. [45]

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Diagnostic Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Model Transfer | Auxiliary and primary tasks are not sufficiently related. [40] | 1. Quantify task similarity using domain knowledge or meta-features.2. Use multiple auxiliary tasks to improve the robustness of knowledge transfer. [40]3. If tasks are heterogeneous, consider methods like "Transfer Learning for Bayesian Optimization on Heterogeneous Search Spaces". [42] |

| Slow Optimization Progress | High-dimensional search space (e.g., many catalyst components & processing parameters). [45] | 1. Perform feature importance analysis to focus on critical variables. [45]2. Use scalable surrogate models (e.g., Random Forests) instead of Gaussian Processes for large spaces. [45]3. Implement a hierarchical approach to first screen broad regions before fine-tuning. |

| Unphysical/Impractical Suggestions | Lack of domain constraints in the model; pure black-box approach. [45] | 1. Manually review and add hard constraints to the search space based on chemical knowledge.2. Use an optimization platform that allows for the incorporation of domain rules and provides explainable predictions (e.g., via SHAP values). [45] |

| Handling Mixed Data Types | Search space contains both continuous (temperature, concentration) and categorical (solvent type, ligand type) variables. [40] | 1. Ensure your MTBO implementation uses a kernel that can handle mixed data types. [40]2. For structured inputs like molecules, use latent-space BO with a variational autoencoder (VAE) to convert molecules into continuous vectors. [44] |

| Noisy or Unreliable Measurements | Inherent experimental variability in catalytic yield or activity measurements. [46] | 1. Use a probabilistic model (like a Gaussian Process) that explicitly accounts for observation noise. [46]2. Incorporate replicate experiments to better quantify noise.3. Use acquisition functions that are robust to noise. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: MTBO for Organic Molecular Metallophotocatalyst Discovery

This protocol is adapted from a study that used a sequential closed-loop BO to discover and optimize organic photoredox catalysts. [37]

1. Define Virtual Library:

- Construct a virtual library of candidate molecules. The cited study used a cyanopyridine (CNP) core and combined 20 β-keto nitriles (Ra) with 28 aromatic aldehydes (Rb) to create 560 virtual molecules. [37]

2. Molecular Encoding:

- Encode each molecule in the library using molecular descriptors that capture key thermodynamic, optoelectronic, and excited-state properties. The study used 16 such descriptors. [37]

3. Initial Experimental Design:

- Select a small, diverse set of initial molecules for synthesis and testing using a space-filling algorithm like Kennard-Stone (KS). The study began with 6 initial molecules. [37]

4. Sequential Closed-Loop Optimization:

- Build a Surrogate Model: Use a Gaussian Process (GP) to model the relationship between molecular descriptors and the experimental outcome (e.g., reaction yield).

- Suggest New Experiments: Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) to select the next batch of promising molecules from the virtual library.

- Run Experiments: Synthesize and test the suggested molecules.

- Update Model: Incorporate the new data and repeat the process. The study used a batch size of 12 molecules per iteration. [37]

5. Reaction Condition Optimization:

- Once promising catalyst candidates are identified, a second BO loop can be run to optimize the reaction conditions (e.g., catalyst loading, ligand concentration). The study evaluated 107 out of 4,500 possible condition sets to reach a high yield. [37]

Protocol 2: MTBO for C–H Activation Reactions in Medicinal Chemistry

This protocol outlines using MTBO to accelerate the optimization of pharmaceutically relevant reactions by leveraging historical data. [40]

1. Task Definition:

- Main Task: The new chemical reaction you wish to optimize (e.g., C-H activation on a precious substrate).

- Auxiliary Task(s): Historical data from previous optimization campaigns of similar reaction classes (e.g., C-H activation with different substrates). [40]

2. Model Setup:

- Replace the standard Gaussian Process in BO with a Multi-task Gaussian Process.

- Train the multi-task GP on the combined data from both the main and auxiliary tasks. This model learns the correlations between them. [40]

3. Iterative Optimization:

- The acquisition function uses the multi-task GP's predictions to suggest experimental conditions that are promising for the main task.

- These experiments are run, and the data is used to update the model.

- The key benefit is that the algorithm can quickly identify high-performing regions of the search space by leveraging patterns learned from the auxiliary data. [40]

Quantitative Results from Case Studies: [40]

| Case Study | Auxiliary Task | Outcome with MTBO |

|---|---|---|

| Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling (Main: Suzuki B1) | Suzuki R1 | Found optimal conditions with P1-L1 (XPhos) faster than single-task BO. |

| Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling (Main: Suzuki B1) | Suzuki R3 & R4 | Achieved better and much faster results due to high task similarity. |

| Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling (Main: Suzuki B1) | Multiple (R1-R4) | Found optimal conditions in fewer than 5 experiments in 20 repeated runs. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational and experimental resources used in MTBO for catalyst discovery.

| Item | Function in MTBO for Catalysis | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | Serves as the core probabilistic surrogate model to approximate the black-box function (e.g., catalyst performance). It provides predictions with uncertainty estimates. [40] [46] | Can be extended to a Multi-task Gaussian Process for knowledge transfer. [41] |

| Molecular Descriptors | Numerical representations that encode key chemical and physical properties of catalyst molecules, enabling the model to learn structure-property relationships. [37] | The metallophotocatalyst study used 16 descriptors for redox potentials, absorption, etc. [37] |

| Latent Space BO with VAE | A technique for optimizing in structured, non-numerical spaces (e.g., molecular structures). A Variational Autoencoder (VAE) maps discrete structures to a continuous latent space where BO is performed. [44] | Used in optimizing antimicrobial peptides and database queries; applicable to catalyst molecules. [44] |

| Acquisition Function | A utility function that guides the selection of the next experiment by balancing exploration (reducing uncertainty) and exploitation (evaluating promising candidates). [46] | Common functions include Expected Improvement (EI) and Upper Confidence Bound (UCB). [46] |

| Historical Reaction Dataset | Serves as the auxiliary task data that provides the prior knowledge for accelerating the optimization of a new, related reaction. [40] | E.g., data from previous Suzuki-Miyaura coupling optimizations. [40] |

Workflow Visualization

MTBO for Catalyst Discovery Workflow

Knowledge Transfer Logic in MTBO

This technical support guide provides a framework for troubleshooting the optimization of Co-Mo/Al₂O₃ catalysts for Carbon Nanotube (CNT) synthesis via wet impregnation. The process is complex, involving multiple interdependent parameters in catalyst preparation and CNT growth. This document, framed within a broader thesis on Bayesian optimization (BO), addresses common experimental challenges and provides detailed protocols to facilitate efficient catalyst development. BO is a machine learning technique that is particularly effective for optimizing "black-box" functions that are expensive to evaluate, such as catalyst synthesis, by balancing exploration of new parameters with exploitation of known high-yield conditions [47] [48].

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My CNT yield is consistently low. What are the primary parameters I should adjust first? A1: Focus on the four key preparation parameters identified by BO [47] [48]:

- Metal Weight Percent: Start within the 1-70 wt.% range. BO often found higher loadings beneficial for yield.

- Co:Mo Ratio: The ratio of Cobalt to Molybdenum is critical. Contour plots from optimization studies suggest that higher Mo content can have a negative effect on carbon yield [47] [49].

- Calcination Temperature: This is a highly sensitive parameter. Optimize within 300–950°C [47] [48].

- Drying Temperature: Also significant; optimize within 80–300°C [47] [48]. Begin by verifying your baseline against the initial database from published BO studies, which used a Sobol sequence for efficient initial space-filling [47] [48].

Q2: During wet impregnation, my metal precursors do not disperse evenly on the Al₂O₃ support. How can I improve this? A2: Uneven dispersion is a common weakness of impregnation methods [50].

- Ensure Sufficient Mixing: The catalyst precursor solution should be stirred for at least 1 hour at room temperature to promote interaction with the support [47] [48].

- Control Solution Volume: In classic Wet Impregnation (WI), an excess of precursor solution beyond the pore volume of the support is used, and the solid is later filtered out [50]. This can sometimes offer more control over the interaction compared to the Incipient Wetness method.

- Consider Advanced Methods: If dispersion remains poor, consider methods like Strong Electrostatic Adsorption (SEA), which controls pH to maximize electrostatic attraction between the metal precursor and the support, leading to higher dispersion and smaller nanoparticles [50].

Q3: My CNT products have high amorphous carbon content. How can I improve their purity? A3: High amorphous carbon indicates suboptimal growth conditions or catalyst deactivation.

- Verify CVD Conditions: Precisely control the synthesis temperature (e.g., 690°C), time (e.g., 10 min), and gas flow rates (e.g., C₂H₄: 30 sccm, H₂: 30 sccm, N₂: 150 sccm) [47] [48]. Use a computer-programmed recipe to eliminate human error.

- Characterize Your Product: Use Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) to quantitatively assess purity by measuring the combustion temperature profile of your sample. Use Raman spectroscopy to determine the IG/ID ratio, a key metric of graphitic order and defect density [47] [48].

- Check Catalyst Activation: Ensure your calcination and reduction steps are correctly generating active metallic nanoparticles. An incorrect calcination temperature can lead to poorly active or sintered catalyst particles.

Troubleshooting Quick Reference Table

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Preparation | Low metal dispersion on support | Lack of strong precursor-support interaction; insufficient mixing [50] | Extend stirring time to 1+ hour; consider pH-controlled SEA method [50] |

| Inconsistent results between batches | Uncontrolled drying process; variable calcination conditions [47] | Standardize drying temperature (80-300°C) and time; ensure consistent furnace temperature profile during calcination (300-950°C) [47] [48] | |

| CNT Synthesis & Yield | Low carbon yield | Suboptimal catalyst composition (Mo too high); incorrect calcination temperature; inefficient CVD conditions [47] [49] | Re-optimize Co:Mo ratio and calcination temp via BO; verify CVD gas flow rates and temperature [47] |

| Product Quality | High amorphous carbon content | Catalyst deactivation; inappropriate C₂H₄ concentration or flow rate [51] | Characterize with TGA/Raman; fine-tune carbon source flow rate and H₂ co-feed; ensure complete catalyst reduction pre-synthesis [47] |

| Uncontrolled CNT diameter/wall number | Incorrect catalyst nanoparticle size | Optimize metal loading and calcination temperature to control nanoparticle size; use a catalyst where Mo prevents Co aggregation (e.g., Mo-Co) [52] |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Wet Impregnation Protocol for Co-Mo/Al₂O₃

This protocol is adapted from the methods used in the Bayesian optimization study [47] [48].

1. Materials:

- Support: Porous Al₂O₃ powder (e.g., 99% purity, 32–63 μm, S({}_{\text{BET}}): 200 m²/g) [47] [48].

- Metal Precursors: Cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) and Ammonium heptamolybdate tetrahydrate ((NH₄)₆Mo₇O₂₄·4H₂O) [47] [48].

- Solvent: Deionized water.

2. Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve calculated masses of cobalt nitrate and ammonium heptamolybdate in deionized water to achieve the target total metal weight percentage (1-70 wt.%) and Co:Mo ratio.

- Impregnation: Add the porous Al₂O₃ support to the precursor solution. Stir the mixture vigorously for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Drying: Separate the solid (by filtration, if using classic WI with excess solution) and dry it while stirring, at a temperature within the optimized range of 80-300°C [47] [48].

- Calcination: Grind the dried powder to a consistent texture. Calcine the powder in a horizontal furnace in an air atmosphere for 2 hours at a temperature within the 300-950°C range [47] [48].

CNT Synthesis via Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD)

1. Equipment Setup:

- Use a horizontal furnace with a quartz tube reactor (e.g., 5.5 cm inner diameter, 1.3 m length).

- Employ mass flow controllers for gases and a computer to program the entire synthesis recipe for reproducibility [47] [48].

2. Standard Growth Recipe:

- Catalyst Mass: 0.01 g of the prepared Co-Mo/Al₂O₃ catalyst.

- Temperature: 690°C.

- Growth Time: 10 minutes.

- Gas Flow Rates:

3. Yield Calculation: Calculate the carbon yield using the formula: [ \text{Carbon yield} (\%) = \frac{Mf - M{\text{cat}}}{M{\text{cat}}} \times 100 ] where (Mf) is the final mass after reaction and (M_{\text{cat}}) is the initial mass of the catalyst [47] [48].

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for the Bayesian optimization of catalyst synthesis and CNT production.

Bayesian Optimization Framework

Core Components of the BO Strategy

Bayesian Optimization is a powerful machine learning approach designed to find the maximum of an expensive-to-evaluate "black-box" function with a minimal number of experiments. Its application to catalyst development is particularly valuable [47] [48] [13].