Bridging the Gap: A Practical Framework for Validating Computational Catalysis Models with Experimental Data

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the critical process of validating computational catalysis models with experimental data.

Bridging the Gap: A Practical Framework for Validating Computational Catalysis Models with Experimental Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the critical process of validating computational catalysis models with experimental data. It explores the foundational principles behind the synergy of computation and experiment, reviews successful methodological approaches including descriptor-based design and high-throughput workflows, addresses common pitfalls and optimization strategies in model-experiment reconciliation, and establishes robust frameworks for comparative analysis and validation. By synthesizing recent advances and practical insights, this review aims to equip catalysis professionals with the knowledge to enhance predictive accuracy and accelerate the discovery of next-generation catalysts.

The Theory-Practice Bridge: Fundamentals of Computational-Experimental Synergy in Catalysis

The traditional approach to understanding catalysis has long relied on the 0K/Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) model, a simplified computational framework that examines potential energy surfaces at absolute zero temperature and infinite dilution [1]. While this model provides a foundational understanding of catalytic mechanisms, it represents conditions starkly different from the high-temperature, high-pressure environments of industrial catalytic processes. The inherent gaps between these idealized models and real-world operation have frequently led to fortuitous agreements or, worse, completely misleading conclusions about how catalysts truly function under working conditions [1].

The catalysis community has addressed this critical limitation by pioneering a paradigm shift toward operando methodology—a term derived from Latin meaning "working"—which encompasses studying catalyst materials under technologically relevant working conditions while simultaneously measuring their catalytic activity and selectivity [2]. This approach, now widespread across fields including electrocatalysis, gas sensors, and battery research, recognizes the dynamic nature of catalyst surfaces that constantly reconstruct and transform in response to their chemical environment [1] [2]. As this comparative guide will demonstrate through experimental data and methodology analysis, operando techniques provide a more accurate, holistic understanding of catalyst structure-activity relationships essential for designing next-generation catalytic systems.

Understanding the Fundamental Limitations of 0K/UHV Models

The 0K/UHV computational model operates on several fundamental assumptions that limit its real-world applicability. These idealized conditions presume that the active site structure remains static and known, that reaction mechanisms remain unchanged by surface coverage effects, and that temperature effects can be safely neglected when transitioning from potential energy surfaces to free energy surfaces [1]. In reality, these assumptions rarely hold true under practical catalytic conditions.

The core limitation stems from what researchers term "material and pressure gaps"—the vast difference between idealized single-crystal surfaces in vacuum versus the complex, nanostructured catalyst materials operating at high pressures and temperatures [2]. Under UHV conditions, reactant adsorption is typically strong, while at realistic operating pressures, the catalyst surface may remain relatively clean due to rapid reaction and desorption [1]. This discrepancy fundamentally alters the perceived reaction mechanism and the very nature of the active sites.

Perhaps most importantly, numerous studies have revealed that catalyst surfaces are dynamic, undergoing significant reconstruction when exposed to reactants. A seminal example comes from atmospheric-pressure scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) studies of CO oxidation, which demonstrated that Pt surfaces reconstruct to form highly active PtO₂-like islands under high oxygen concentrations—a phenomenon that could not be predicted by 0K/UHV models [2]. Similarly, Pd surfaces exhibit oscillatory CO oxidation behavior due to the formation and disappearance of active nano-oxide phases [2]. These dynamic reconstructions mean the true active site may only exist under specific reaction conditions, rendering pre-determined static models insufficient for accurate mechanistic understanding.

The Operando Approach: Principles and Methodological Framework

Operando methodology formally integrates spectroscopic characterization with simultaneous activity measurement under genuine working conditions, creating a direct link between observed catalyst states and their functional performance [3] [2]. This approach requires carefully designed reactors that balance the technical requirements of spectroscopic techniques with conditions that yield catalytically relevant performance data.

Defining Operando Conditions

The term "operando" was intentionally coined to distinguish from simpler "in situ" approaches. While in situ techniques are performed under simulated reaction conditions (e.g., elevated temperature, applied voltage, presence of solvents), operando techniques require the catalyst to be under conditions as close as possible to real operation while its activity is being simultaneously measured [3]. This critical distinction ensures that the characterized catalyst state corresponds directly to its functional state, eliminating uncertainties from post-reaction characterization or non-representative environments.

A key principle of operando methodology is addressing phenomena across multiple length scales, from atomic-level surface processes to concentration gradients within catalyst pellets and reactors [2]. On the laboratory or industrial scale, catalyst pellets packed in reactors inherently create concentration gradients of reactants, products, and intermediates in both axial and radial directions [2]. Within catalyst pellets, further concentration gradients arise, while atomic-scale surface processes create additional heterogeneities. These multi-scale gradients directly influence surface chemistry by affecting fluid-phase concentrations, making their understanding essential for comprehensive catalytic insight.

Reactor Design Considerations

Operando methodology faces significant engineering challenges in reactor design, where compromises often exist between optimal characterization conditions and realistic catalytic environments. Many operando reactors are designed for batch operation with planar electrodes, while benchmarking reactors typically employ electrolyte flow or gas diffusion electrodes to control convective and diffusive transport [3]. This mismatch can lead to poor mass transport of reactants to the catalyst surface and changes in electrolyte composition (e.g., pH gradients), creating microenvironments that differ from practical systems and potentially leading to mechanistic misinterpretations [3].

Innovative reactor designs are overcoming these limitations. For differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS), some researchers have deposited CO₂ reduction catalysts directly onto the pervaporation membrane, eliminating long path lengths between the catalyst surface and the mass spectrometry probe [3]. This modification enabled detection of much higher concentrations of reactive intermediates like acetaldehyde and propionaldehyde compared to bulk measurements [3]. Similarly, for grazing incidence X-ray diffraction (GIXRD), careful optimization of X-ray transmission through liquid electrolyte and beam interaction area at the catalyst surface minimizes signal attenuation while ensuring sufficient surface area interaction for useful signals [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional vs. Advanced Operando Reactor Designs

| Reactor Aspect | Traditional Design | Advanced Operando Design | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Transport | Batch operation, planar electrodes | Flow systems, gas diffusion electrodes | Reduces artificial concentration gradients |

| Detection Path | Long path between catalyst and detector | Catalyst deposited directly on detection window | Improves response time and intermediate detection |

| Current Density | Typically low (<10 mA/cm²) | Approaches industrial relevance (>100 mA/cm²) | Increases practical significance of mechanistic insights |

| Beam Interaction | Compromised by electrolyte attenuation | Co-optimized for signal and reaction conditions | Enhances signal-to-noise ratio for faster acquisition |

Comparative Analysis: Key Techniques and Experimental Protocols

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS)

Operando XAS provides powerful insight into the local electronic and geometric structure of catalytic active centers under reaction conditions, with synchrotron-based sources offering high time resolution for tracking dynamic changes [3] [2].

Experimental Protocol: Operando XAS for electrocatalysis typically involves a specialized electrochemical cell with X-ray transparent windows (e.g., Kapton film) that allows the beam to interact with the catalyst layer while maintaining controlled potential/current conditions in relevant electrolytes. The catalyst is typically deposited as a thin film on a conductive substrate, with careful attention to thickness optimization for sufficient signal while maintaining mass transport characteristics. Measurements are performed simultaneously with electrochemical activity monitoring, often using reference electrodes for accurate potential control and accounting for ohmic losses [2].

Case Study - Mn Single-Atom Catalysts: Researchers constructed Mn single-atom catalysts anchored on sulfur and nitrogen-modified carbon carriers (MnSAs/S-NC) and confirmed the stable Mn-N₄-CxSy structure through XAS [2]. Operando XAS results revealed that the ORR activity increased during the oxygen reduction reaction process due to isolated bond-length extension in the low-valence Mn-N₄-CxSy moiety, demonstrating the dynamic nature of the active site under working conditions [2].

Case Study - Cu Single-Atom Catalysts: Another study demonstrated the dynamic behavior of CuN₂C₂ sites in ORR, linking structural changes to catalytic performance. Operando XAS combined with DFT calculations showed that CuN₂C₂ active sites undergo geometric distortion in response to new oxygen-containing coordination species during ORR [2]. This distortion was more pronounced on highly curved carbon nanotube substrates, leading to optimal electron transfer to adsorbed O₂ molecules and significantly enhanced ORR activity.

Vibrational Spectroscopy (IR and Raman)

Operando infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy techniques detect molecular vibrations that provide information about reaction intermediates, surface species, and catalyst structure transformations during operation.

Experimental Protocol: Operando vibrational spectroscopy requires specialized cells with optical windows transparent to the relevant spectroscopic range (e.g., CaF₂ or BaF₂ windows for IR spectroscopy). For electrocatalytic systems, the cell incorporates working, counter, and reference electrodes while allowing illumination and collection of scattered light. Isotope labeling (e.g., ¹⁸O or D) is often employed to distinguish between reaction intermediates and spectator species. Background spectra collected under reference conditions (e.g., in electrolyte without applied potential) are subtracted to highlight changes induced by the reaction [3] [4].

Implementation Considerations: A significant challenge in operando IR spectroscopy lies in discriminating against strong signals from the electrolyte phase, particularly for aqueous systems. Approaches to address this include using thin-layer configurations, attenuated total reflection (ATR) geometries, and modulation techniques that enhance sensitivity to surface species [4].

Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (ECMS)

ECMS directly couples an electrochemical cell with a mass spectrometer, enabling real-time detection of volatile reactants, intermediates, and products during electrocatalysis. This provides crucial information about reaction pathways and selectivity.

Experimental Protocol: In ECMS, the electrochemical cell features a porous working electrode positioned adjacent to a pervaporation membrane that separates the electrolyte compartment from the mass spectrometer vacuum chamber. Volatile species generated at the electrode surface diffuse through the membrane and are ionized in the mass spectrometer source for detection. Careful calibration with standard solutions allows quantification of reaction products. The system requires meticulous sealing to maintain electrochemical integrity while allowing efficient species transport to the mass spectrometer [3].

Advanced Implementation: To address response time limitations, researchers have developed configurations where the catalyst is deposited directly onto the pervaporation membrane, significantly reducing the path length between reaction site and detection [3]. This approach has enabled detection of reactive intermediates like acetaldehyde and propionaldehyde in CO₂ reduction at concentrations much higher than measurable in the bulk electrolyte, providing new insights into reaction mechanisms [3].

Single Particle Plasmonic Nanospectroscopy

This emerging technique enables individual nanoparticle resolution under operando conditions, revealing heterogeneity and dynamic behavior that ensemble measurements obscure.

Experimental Protocol: Researchers have developed nanofluidic "model pores" that combine nanofluidics with single-particle plasmonic readout and online mass spectrometry [5]. The platform consists of a nanofluidic chip connected to a gas handling system compatible with up to 4 bar pressure, with an on-chip heater enabling operation up to 723 K. Single metal nanoparticles fabricated inside nanochannels serve as plasmonic sensors, with scattering spectra sensitive to structural and chemical changes in the nanoparticles and their immediate environment [5]. This allows correlation of individual nanoparticle state with ensemble activity measured simultaneously by mass spectrometry.

Application Example: In CO oxidation over Cu nanoparticles, this technique directly visualized how reactant concentration gradients due to conversion on upstream nanoparticles dynamically control the oxidation state and activity of particles downstream [5]. This provided direct evidence of how mass transport constraints in confined environments create varying operational regimes for individual nanoparticles within the same catalyst.

Table 2: Comparison of Operando Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Key Information | Time Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Key Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XAS | Local electronic structure, oxidation state, coordination geometry | Seconds to milliseconds (with synchrotron) | ~1 μm (microfocus) | Beam transparency of cell windows, sample thickness optimization |

| IR Spectroscopy | Molecular identity of surface species, reaction intermediates | Milliseconds to seconds | Diffraction-limited (~10 μm) | Signal dominance by electrolyte phase, requires thin-layer cells |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Molecular vibrations, catalyst phase transformations | Seconds | Diffraction-limited (~1 μm) | Fluorescence interference, potential laser-induced sample damage |

| ECMS | Product distribution, reactive intermediates | Sub-second to seconds | N/A (ensemble measurement) | Membrane transport efficiency, calibration for quantification |

| Plasmonic Nanospectroscopy | Single nanoparticle oxidation state, local environment | Milliseconds | ~10 nm | Particle-to-particle variability, complex nanofabrication |

Computational Modeling Approaches for Realistic Conditions

The transition from 0K/UHV to operando conditions in computational modeling has been enabled by several methodological developments designed to address the complexity of realistic catalytic environments.

Methodological Framework

Computational chemists have developed multiple approaches to bridge the gap between simplified models and operando conditions, often applied in combination:

- Global Optimization Techniques: Heuristic methods that search multidimensional potential energy surfaces to identify relevant catalyst configurations and active site structures that may not be intuitively obvious [1].

- Ab Initio Constrained Thermodynamics: Approaches that account for the effects of temperature and pressure on catalyst surface structure and composition by calculating surface free energies as functions of environmental variables [1].

- Biased Molecular Dynamics: Enhanced sampling methods that facilitate the location of transition states in complex environments where surrounding molecules significantly influence reaction pathways [1].

- Microkinetic Modeling: Framework for simulating complex reaction networks that account for the coverage of multiple reaction intermediates and their effects on catalytic rates [1].

- Machine Learning Approaches: Emerging methods that identify patterns and correlations in large datasets, potentially bypassing the need for explicit physical modeling while maintaining predictive power [1].

Implementation Workflow

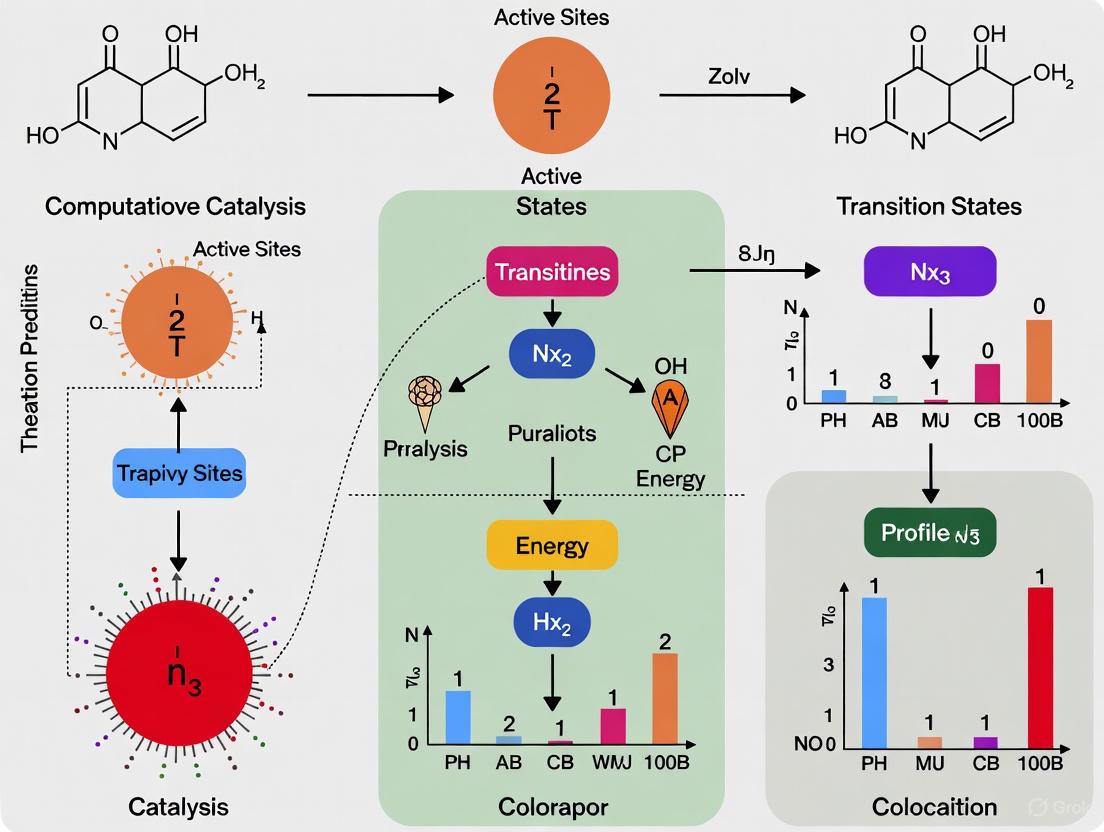

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between these computational methods in the transition from idealized to operando models:

Computational Path to Realistic Models

This framework demonstrates how multiple computational techniques combine to progressively build more realistic models of catalytic systems, moving from idealized single-crystal surfaces at 0K to dynamic, environment-dependent representations that closely mirror operando experimental conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Operando Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Operando Studies | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ion-Exchange Membranes | Separation of electrochemical compartments while allowing ion transport | Nafion for proton exchange in fuel cell studies |

| X-ray Transparent Windows | Allows spectroscopic probe access while maintaining reaction conditions | Kapton or polyimide films for XAS and XRD cells |

| Reference Electrodes | Provides stable potential reference in electrochemical systems | Ag/AgCl for aqueous systems, Li reference for non-aqueous |

| Isotope-Labeled Reactants | Tracing reaction pathways and identifying intermediates | ¹⁸O₂ for oxygen evolution studies, ¹³CO for CO oxidation |

| Plasmonic Nanoparticles | Optical probes for local environment and oxidation state changes | Au-Pd core-shell structures for single-particle spectroscopy |

| Nanofluidic Chips | Confined environments mimicking porous catalyst supports | Silicon-based nanofabricated channels for single-particle studies |

| Synchrotron Radiation | High-intensity X-ray source for time-resolved studies | Tracking catalyst oxidation state changes during operation |

The critical shift from 0K/UHV models to operando conditions represents more than just a technical improvement—it constitutes a fundamental transformation in how we understand and design catalytic systems. By directly linking catalyst structure with performance under realistic working conditions, operando methodologies close the gaps that have long separated computational prediction, laboratory synthesis, and industrial application.

The most powerful insights emerge from multi-technique approaches that combine complementary operando methods, simultaneously providing information about electronic structure, molecular species, and product distributions [6]. Furthermore, the integration of computational modeling with experimental operando data creates a virtuous cycle of hypothesis generation and validation, accelerating the discovery and optimization of next-generation catalysts.

As operando methodologies continue to advance, key challenges remain in improving spatiotemporal resolution, implementing more realistic reactor environments, and developing more sophisticated data analysis tools to extract meaningful information from complex multi-technique datasets. However, the foundational principle remains clear: understanding catalysis requires observing it as it functions, not as we idealize it to be. This paradigm shift toward operando conditions promises to unlock new frontiers in catalyst design for sustainable energy and chemical production.

The traditional view of a catalyst depicts a static surface with fixed active sites. However, a paradigm shift is underway, recognizing that catalysts are dynamic entities whose active sites transform under realistic operational conditions. For researchers validating computational models with experimental data, this dynamism presents both a challenge and an opportunity. The very nature of what constitutes an "active site" changes under the influence of temperature, pressure, and reactant environments, meaning that computational models must evolve beyond idealized static structures to accurately predict catalytic behavior.

This guide examines how modern experimental techniques are revealing these dynamic transformations and compares their observations with predictions from computational models. By directly comparing data from advanced characterization and computational simulations, we provide a framework for researchers to validate their models against the true, non-equilibrium state of working catalysts, ultimately enabling the design of more efficient and stable catalytic systems for applications ranging from chemical synthesis to drug development.

Experimental Insights into Catalyst Dynamics

Direct Observation of Dynamic Restructuring

Advanced in situ and operando characterization techniques have fundamentally changed our ability to observe catalysts under working conditions. In situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) allows for real-time visualization and analysis of structural and chemical changes in materials at the nanoscale under various conditions, including gas or liquid environments, while external stimuli like heating or biasing are applied [7]. When these morphological or compositional observations are simultaneously correlated with measurements of catalytic properties (e.g., activity and selectivity), the approach is termed operando TEM, which directly establishes structure-property relationships in catalytic materials [7].

A key finding from these studies is the phenomenon of restructuring-induced catalytic activity. For Cu-based electrocatalysts, a fundamental question is whether activity originates from the original (as-synthesized) sites or from sites created through dynamic transformation under operational conditions [8]. Evidence suggests that if performance primarily stems from restructuring-induced states, catalyst design must focus on harnessing these dynamic transformations rather than attempting to avoid them.

The Collectivity Effect in Cluster Catalysis

Research on subnanometer metal clusters has revealed a collectivity effect, where numerous sites across varying sizes, compositions, isomers, and locations collectively contribute to overall activity [9]. Artificial intelligence-enhanced multiscale modeling shows that these sites, despite their distinct local environments, configurations, and reaction mechanisms, work in concert due to their high intrinsic activity and considerable population.

Table 1: Experimental Techniques for Probing Dynamic Active Sites

| Technique | Key Capabilities | Spatial/Temporal Resolution | Key Insights into Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| In situ/Operando TEM [7] | Real-time visualization of structural & chemical changes under reaction conditions (gas/liquid, heating, biasing). | Atomic spatial resolution (down to ~50 pm); temporal resolution varies. | Direct observation of surface restructuring, nanoparticle sintering, and phase transitions during reaction. |

| Machine Learning-enhanced Multiscale Modeling [9] | Exhaustively explores configuration space of cluster catalysts under operational conditions; integrates statistical site populations. | N/A (Computational) | Reveals collective contribution of multiple sites (different sizes, isomers, locations) to overall activity. |

| In situ X-ray Spectroscopy (XAS, XPS) | Monitors chemical state and local coordination of active sites under reaction conditions. | Element-specific; time-resolved studies possible. | Tracks oxidation state changes and adsorbate-induced surface reconstruction. |

Bridging Computation and Experiment

The Rise of Machine Learning in Catalysis

Traditional computational approaches coupling Density Functional Theory with microkinetic modeling have been a cornerstone of rational catalyst design [10]. However, their prohibitive computational cost often limits application to simple reaction networks over idealized catalyst models. Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) have emerged as a transformative alternative, estimating electronic structure properties at near-quantum accuracy for a fraction of the cost [10]. These models, trained on large-scale DFT databases, enable studies of reaction network complexity and catalyst structural dynamics that were previously inaccessible [10].

A critical challenge in model validation is the treatment of magnetism in computational datasets. Spin-polarized DFT calculations are essential for accurate modeling of industrially relevant catalysts based on earth-abundant first-row transition metals (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni), which exhibit strong spin polarization effects on binding energies and activation barriers [10]. The omission of spin in many large-scale datasets limits the accuracy of resulting models for processes like ammonia synthesis and Fischer-Tropsch synthesis [10].

Comparative Analysis: Computational Predictions vs. Experimental Observations

Table 2: Computational vs. Experimental Observations of Catalyst Dynamics

| Catalytic System | Computational Prediction | Experimental Observation | Level of Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu/CeO₂ Clusters (CO Oxidation) [9] | AI-enhanced multiscale modeling predicts a "collectivity effect" with multiple sites (across isomers/sizes) contributing to activity. | Agreement between computed mechanisms/kinetics and experimental data validates the collective effect. | High: Quantitative agreement in kinetics. |

| Cu-based Electrocatalysts [8] | Models may predict activity based on static, as-synthesized structures. | In situ/operando techniques reveal that restructuring-induced sites often dominate catalytic activity. | Variable: Highlights need for dynamic models. |

| Magnetic Transition Metal Catalysts (e.g., Fe, Co) [10] | Standard (non-spin-polarized) MLIPs may predict adsorption energies and barriers. | High-fidelity spin-polarized calculations show significant deviations due to magnetic effects. | Incomplete: Calls for improved datasets and models that include spin. |

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for validating dynamic catalyst models, combining computational and experimental approaches.

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodologies

Essential Research Toolkit

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Studying Dynamic Catalysts

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| In Situ TEM Microreactors (MEMS) [7] | Enables high-resolution imaging of catalysts under realistic gas/ liquid environments and elevated temperatures. | Crucial for visualizing structural dynamics (restructuring, sintering) at the atomic scale during reaction. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) [10] | Surrogate models for DFT that allow for accelerated sampling of catalyst dynamics and reaction pathways. | Models like eSEN, EquiformerV2, UMA; trained on large datasets (e.g., OC20, AQCat25). |

| Spin-Polarized DFT Codes (VASP) [10] | Provides high-fidelity reference data for magnetic catalyst systems, accounting for electron spin. | Essential for accurate modeling of Fe, Co, Ni-based catalysts; used to generate training data for advanced MLIPs. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) & Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) [9] | Computational methods for sampling the vast configuration space of cluster catalysts under operational conditions. | Identifies stable and metastable structures and their distributions under reaction conditions. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: AI-Enhanced Multiscale Modeling of Cluster Catalysts

The following protocol, adapted from a study on Cu/CeO₂ clusters for CO oxidation, outlines a comprehensive approach for integrating computational and experimental data to model dynamic active sites [9]:

Structure Sampling via M-GCMC with ANNPs:

- Employ Genetic Algorithm (GA)-driven modified Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (M-GCMC) simulations to determine the structure and composition of supported clusters under reaction conditions.

- Accelerate simulations using Artificial Neural Network Potentials (ANNPs) to sample over 100,000 cluster structures.

- Identify the distribution and concentrations of all relevant clusters (including metastable ones) under thermodynamic equilibrium using Boltzmann statistics.

Site-Resolved Microkinetic Analysis:

- For each identified cluster isomer, optimize reaction pathways for all exposed sites.

- Calculate isomer- and site-resolved intrinsic reaction rates using first-principles microkinetics.

- Classify sites with identical local coordination and coordinated reactants/intermediates across all clusters as a single site type.

Integration of Collective Activity:

- Compute the overall catalytic activity by integrating the intrinsic activity of all available sites, weighted by their statistical distribution.

- Use the formula for the average reaction rate per site (Ro), which sums contributions from all cluster sizes, isomers, and exposed sites:

- Ro = Σ pn Rn

- Where Rn = Σ (Pn, iso × Rn, iso)

- And Rn, iso = Σ (pn, iso, site × rn, iso, site)

Data-Driven Descriptor Identification:

- Apply interpretable machine learning algorithms (e.g., SISSO) to build physically meaningful descriptors of activity from geometric and energy features.

- This step helps uncover the fundamental principles governing the collective catalytic behavior, such as the balance between local atomic coordination and adsorption energy.

Diagram 2: AI-enhanced multiscale modeling workflow for capturing collective catalysis [9].

The evidence from both cutting-edge experiments and advanced computations unequivocally demonstrates that the active site is not a static entity but a dynamic one, often born from the reaction environment itself. This has profound implications for validating computational models. Successful models must now account for the statistical distribution of multiple active sites, the restructuring of catalysts under operational conditions, and critical physical details like spin polarization. The convergence of operando characterization and machine-learning-enhanced simulation is creating a new paradigm where models are not just validated against a single snapshot of a catalyst, but against its entire life cycle under working conditions. This holistic approach to validation, which embraces the dynamic nature of catalysis, is the key to unlocking the next generation of high-performance, rationally designed catalysts.

In computational catalysis research, the validation of predictive models depends on the synthesis of diverse and disparate data types. Modern catalysis studies combine data from density functional theory (DFT) calculations, high-throughput experiments, and characterization techniques, creating a complex data landscape often scattered across different systems and formats [11]. This fragmentation creates significant data silos, where valuable insights remain locked away in isolated, underutilized datasets, impeding the pace of scientific discovery [11]. The integration challenge is further compounded by issues of data heterogeneity, where sources vary in structure, format, and semantics, and stringent privacy and regulatory concerns that govern sensitive research data [11] [12].

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative solution to these challenges, serving as the common language that can unify disparate data types. ML acts as a theoretical engine that contributes to mechanistic discovery and the derivation of general catalytic laws, evolving beyond a mere predictive tool [13]. By leveraging ML, researchers can bridge the gap between data-driven discovery and physical insight, creating validated, multi-physics models that accelerate the design of novel catalysts. This paradigm shift enables a new research framework where ML seamlessly integrates computational and experimental data, providing a robust foundation for model validation and scientific advancement.

Machine Learning Approaches for Data Integration

The application of machine learning in data integration spans a hierarchical framework, from initial data processing to advanced symbolic regression. This section outlines the key ML techniques and their specific applications in unifying disparate catalytic data.

A Hierarchical Framework for ML in Catalysis

Machine learning applications in catalysis progress through three conceptually distinct stages:

Data-Driven Screening and Prediction: At this foundational level, ML models, particularly graph neural networks (GNNs), are trained on large datasets to predict catalytic properties such as adsorption energies, reaction pathways, and activity descriptors [13]. These models learn from existing DFT and experimental data to make rapid predictions for new catalyst compositions and structures.

Physics-Based Modeling and Mechanism Elucidation: Moving beyond pure prediction, ML integrates physical laws and constraints to ensure models are not only accurate but also physically interpretable [13]. Techniques such as symbolic regression and feature engineering based on domain knowledge help bridge data-driven patterns with fundamental catalytic principles.

Symbolic Regression and Theory-Oriented Interpretation: At the most advanced stage, ML techniques like the SISSO (Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) method help identify optimal descriptors and mathematical expressions that capture the underlying physics of catalytic processes [13]. This represents the highest level of integration, where ML directly contributes to theoretical understanding.

Technical Use Cases of ML in Data Integration

Table 1: Machine Learning Use Cases in Data Integration for Catalysis

| Use Case | Technical Implementation | Relevance to Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Data Discovery & Mapping | AI algorithms automatically identify, classify, and map data structures [12]. | Maps relationships between DFT calculations, experimental results, and material descriptors. |

| Data Quality Improvement | ML and NLP detect and correct data anomalies, inconsistencies, and errors [12]. | Ensures reliability of integrated datasets from multiple computational and experimental sources. |

| Metadata Management | Automated metadata generation extracts information about data lineage and quality [12]. | Tracks origins and transformations of catalytic data, which is crucial for model validation. |

| Real-Time Data Integration | Continuous monitoring of data sources triggers ingestion when changes are detected [12]. | Enables live updating of catalytic models with new experimental or computational results. |

| Scalability & Performance | AI-powered platforms handle large data volumes and complex processing tasks [12]. | Manages the exponential growth of data from high-throughput catalysis experiments. |

Specialized Data Integration Solutions for Catalysis Research

The integration of disparate data in catalysis requires specialized approaches that address the field's unique challenges:

Multi-Physics Integration Protocols: Advanced frameworks enable direct synergy between complementary datasets. For instance, integrating spin-polarized calculations from resources like AQCat25 with the extensive solvent-environment data from OC25 requires specialized techniques to prevent catastrophic forgetting of original dataset knowledge [14]. Effective methods include joint training with "replay" (mixing old and new physics/fidelity samples during optimization) and explicit meta-data conditioning using approaches like Feature-wise Linear Modulation (FiLM) [14].

Cross-Border Data Collaboration: Privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) such as homomorphic encryption and secure multi-party computation enable collaborative research on sensitive data without exposing the underlying information [11]. This is particularly valuable for international research consortia working on proprietary catalyst systems while needing to comply with data protection regulations.

Automated Feature Engineering: ML algorithms automatically construct meaningful material descriptors from raw data, reducing reliance on manual feature selection based on domain expertise alone. Techniques such as autoencoders and representation learning create optimized feature spaces that integrate information from multiple data sources [13].

Experimental Benchmarking: Performance Comparison of ML Models

Rigorous experimental benchmarking is essential for validating the performance of ML approaches in integrating and predicting catalytic properties. The Open Catalyst 2025 (OC25) dataset provides a standardized platform for comparing model performance across diverse catalytic environments.

Dataset Composition and Experimental Design

The OC25 dataset represents a significant advancement in catalysis research infrastructure, comprising 7.8 million DFT calculations across 1.5 million unique explicit solvent microenvironments [14]. This comprehensive dataset includes:

- Surfaces: 39,821 unique bulk materials with all symmetrically distinct low-index facets (Miller index ≤ 3) enumerated and randomly tiled [14]

- Adsorbates: 98 molecules, including all OC20 species and 13 additional reactive intermediates [14]

- Solvents and Ions: Eight common solvents and nine inorganic ions, with water most prevalent and ions present in approximately 50% of structures [14]

- Elemental Coverage: Surfaces, adsorbates, solvents, and ions collectively span 88 elements [14]

- System Size and Diversity: Average system contains ~144 atoms (range 80-300) [14]

The dataset defines a "pseudo-solvation energy" (ΔEsolv) for each adsorbed configuration, calculated as ΔEsolv ≡ ΔEadssolv - ΔEadsvac, enabling direct comparison of solvent effects on catalytic properties [14].

Quantitative Performance Metrics of ML Models

Table 2: Performance Comparison of ML Models on OC25 Benchmark Dataset

| Model Architecture | Parameters | Energy MAE [eV] | Forces MAE [eV/Å] | ΔE_solv MAE [eV] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eSEN-S (direct) | 6.3M | 0.138 | 0.020 | 0.060 |

| eSEN-S (conserving) | 6.3M | 0.105 | 0.015 | 0.045 |

| eSEN-M (direct) | 50.7M | 0.060 | 0.009 | 0.040 |

| UMA-S (finetune) | 146.6M | 0.091 | 0.014 | 0.136 |

The benchmarking results demonstrate several key trends. The eSEN-M (direct) model achieves the lowest overall test mean absolute errors (MAEs) across all three metrics [14]. The conserving variant of eSEN-S, which guarantees force conservation via direct autograd (F = -∇E), shows improved performance over the direct variant that forbids explicit force conservation [14]. All OC25-trained models exhibit substantial improvement over previous benchmarks, with force errors decreasing by >50% and solvation energy errors by >2× relative to models trained on earlier datasets like OC20 [14].

Integration Workflow for Multi-Physics Catalysis Data

The process of integrating disparate data sources for catalytic machine learning follows a systematic workflow that ensures data compatibility and model robustness:

This workflow highlights the iterative refinement process essential for validating computational models against experimental data. The integration of multiple physics domains through techniques like FiLM conditioning enables models to maintain performance across different data types and fidelity levels [14].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Catalytic ML

Implementing effective ML-driven data integration requires a suite of specialized tools and reagents. The following table catalogs essential solutions for researchers in computational catalysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML in Catalysis

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset Platforms | Open Catalyst 2025 (OC25), AQCat25, Materials Project | Provide standardized, large-scale datasets for training and benchmarking ML models on catalytic properties [14]. |

| ML Model Architectures | eSEN (expressive smooth equivariant networks), UMA (Universal Models for Atoms) | GNNs engineered for atomistic property prediction on large, compositionally complex systems [14]. |

| Data Integration Tools | Databricks, Google Cloud Data Fusion, Apache Kafka with Kafka-ML | Platforms for managing data pipelines efficiently, leveraging AI to automate workflows and enhance scalability [12]. |

| Privacy-Enhancing Technologies | Homomorphic Encryption, Secure Multi-Party Computation | Enable collaborative analysis of sensitive data without exposing underlying information, addressing regulatory concerns [11]. |

| Symbolic Regression Methods | SISSO (Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) | Identify optimal descriptors and mathematical expressions that capture underlying physics of catalytic processes [13]. |

| Cross-Domain Validation | Joint training with "replay", Meta-data conditioning (FiLM) | Prevent catastrophic forgetting when integrating multiple data sources and maintain performance across domains [14]. |

Comparative Analysis of Integration Approaches

Different ML strategies offer varying advantages for integrating disparate data types in catalysis research. The choice of approach depends on the specific data characteristics and research objectives.

Performance Across Data Types and Environments

The benchmarking data reveals how different ML architectures perform across various data integration challenges:

Lightweight vs. Large Models: While high-performing machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) often push model capacity to hundreds of millions of parameters (e.g., UMA-S with 146.6M parameters), OC25 benchmarking demonstrates the competitiveness of lightweight geometric message-passing approaches with significantly fewer parameters [14]. This indicates that model architecture and training strategies can compensate for parameter count in data integration tasks.

Out-of-Distribution Generalization: Models face significant challenges when generalizing to unseen data distributions. For example, the out-of-distribution (OOD) energy MAE for eSEN-S (conserving) rises to 0.186 eV for the "both" split (unknown bulks + unknown solvents) compared to 0.105 eV on the test set [14]. This performance drop highlights the difficulty of integrating data from completely novel catalytic environments.

Multi-Fidelity Integration: Techniques that combine data from different levels of theory (e.g., standard DFT with higher-fidelity calculations) require special handling. Training on data with different convergence criteria (e.g., EDIFF=1e-4 eV vs. EDIFF=1e-6 eV) demonstrates that models can maintain robustness to label noise when properly designed [14].

Workflow for ML-Driven Catalyst Discovery and Validation

The integration of ML with traditional catalytic research follows a structured workflow that bridges computation and experiment:

This workflow emphasizes the active learning loop where experimental results continuously refine the ML models, which in turn guide subsequent experimental cycles. This iterative process represents the most effective approach for integrating computational and experimental data in catalysis research.

Machine learning has fundamentally transformed the integration of disparate data types in computational catalysis, serving as a common language that unifies diverse data sources into coherent, predictive models. The benchmarking results demonstrate that modern ML architectures, particularly graph neural networks like eSEN and UMA, can achieve remarkable accuracy in predicting key catalytic properties across diverse chemical environments [14]. The hierarchical application framework—progressing from data-driven screening to physics-based modeling and ultimately to symbolic regression and theoretical interpretation—provides a structured pathway for leveraging these technologies [13].

The most successful implementations recognize that ML is not merely a replacement for traditional methods but a theoretical engine that enhances human understanding [13]. By embracing privacy-enhancing technologies for secure collaboration [11], standardized benchmarking datasets like OC25 [14], and robust multi-physics integration protocols [14], the catalysis research community can accelerate the discovery and validation of novel catalysts. As these technologies continue to mature, the seamless integration of disparate data types through machine learning will increasingly become the foundation for advances in sustainable energy, environmental protection, and efficient chemical production.

From Prediction to Synthesis: Methodologies for Computationally-Driven Catalyst Discovery

In computational catalysis, descriptor-based design has emerged as a powerful paradigm for rational catalyst development, bridging complex theoretical calculations with experimental validation. This approach identifies key adsorption energies and electronic properties that govern catalytic activity, which can be visualized through volcano plots to pinpoint optimal catalyst formulations. The foundational Sabatier principle states that an ideal catalyst should bind reaction intermediates neither too strongly nor too weakly, creating a balanced energy landscape that maximizes reaction rate [15]. Volcano plots graphically represent this principle by plotting catalytic performance (e.g., turnover frequency) against a descriptor variable (e.g., adsorption energy), revealing the characteristic volcano shape where the peak corresponds to the optimal descriptor value [16] [15].

This guide compares the performance of different descriptor-based design strategies, from traditional density functional theory (DFT) calculations to modern machine learning (ML) approaches, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies based on their specific catalytic systems and available resources. By validating computational predictions with experimental data, researchers can accelerate the discovery of novel catalysts for energy conversion, environmental remediation, and pharmaceutical development.

Theoretical Foundations: From Adsorption Energies to Activity Descriptors

Fundamental Descriptors in Heterogeneous Catalysis

At the core of descriptor-based design lies the identification of physicochemical properties that correlate with catalytic activity. The d-band model serves as a fundamental electronic descriptor for transition metal catalysts, where the energy center of the d-band states relative to the Fermi level determines adsorption strength [17]. This model has been successfully applied to predict trends in atomic adsorption behavior, with shifts in d-band center correlating with changes in adsorption energies [17]. For zeolite catalysts featuring isolated metal atoms as Lewis acid sites, the dissociative adsorption energy of methane (ΔHCH3-H) has been identified as a simple yet effective activity descriptor for dehydrogenation reactions [16].

Linear free energy scaling relationships (LFESRs) further simplify catalyst screening by revealing that energies of reaction intermediates and transition states often correlate linearly with a single descriptor value for a family of materials with similar bonding characteristics [15]. These relationships enable the reduction of complex reaction networks to a single descriptor variable, making high-throughput screening computationally feasible.

Volcano Plots as Predictive Tools

Volcano plots transform descriptor-activity relationships into powerful predictive tools by combining LFESRs with microkinetic modeling [16] [15]. The plot's apex represents the Sabatier optimum, where all elementary reaction steps are balanced for maximum activity. First-principles volcano plots constructed from DFT computations and LFESRs provide valuable mechanistic insights, while empirical volcanoes derived from experimental observations help identify descriptors for reactions with unknown or complex mechanisms [15].

Table 1: Classification of Common Catalytic Descriptors

| Descriptor Category | Specific Examples | Computational Cost | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic | d-Band Center (DBC), d-Band Width (DBW), Work Function (WF) | High | Transition metal surfaces, alloy catalysts |

| Elemental | Valence Electrons (VE), Sublimation Energy (SE), Ionization Energy (IE) | Low | Initial screening, trend identification |

| Structural | Generalized Coordination Number (GCN), Ensemble Atom Count (EAC) | Medium | Bimetallic catalysts, surface alloys |

| Adsorption-Based | ΔHCH3-H, Hydrogen Affinity (EH), Binding Energy of H₂ (BEH₂) | High | Dehydrogenation, hydrogenation reactions |

Computational Methodologies: From DFT to Machine Learning

Density Functional Theory Calculations

DFT remains the cornerstone for calculating adsorption energies and electronic properties in descriptor-based design. Standardized protocols ensure consistent and comparable results across different catalytic systems:

Surface Model Construction: For transition metal catalysts, low-index crystal surfaces (e.g., fcc(111)) are typically modeled using periodic slabs with 3-5 atomic layers [17]. A vacuum space of ≥15 Å prevents interactions between periodic images in the z-direction.

Adsorption Energy Calculation: The adsorption energy (Eads) is calculated as Eads = Etotal - Esurface - Eadsorbate, where Etotal is the energy of the surface with adsorbed species, Esurface is the energy of the clean surface, and Eadsorbate is the energy of the isolated adsorbate molecule [17].

Electronic Property Analysis: Projected density of states (PDOS) calculations determine the d-band center using the formula εd = ∫ E ρd(E) dE / ∫ ρd(E) dE, where ρd(E) is the density of d-states [17].

For zeolite catalysts, cluster or periodic models represent the microporous framework, with embedded metal cations serving as Lewis acid sites [16]. The Bayesian error estimation functional with van der Waals interactions (BEEF-vdW) provides accurate energy calculations for both metallic and zeolitic systems [16].

Machine Learning Approaches

ML algorithms accelerate descriptor discovery and adsorption energy prediction by learning complex patterns from existing datasets:

Feature Engineering: Initial feature sets include elemental properties (electronegativity, valence electrons), structural parameters (coordination numbers), and electronic descriptors (d-band characteristics)[ccitation:2] [17]. Feature selection techniques like permutation feature importance (PFI) identify the most relevant descriptors [17].

Model Training: Ensemble methods like random forest regression (RFR) and Gaussian process regression (GPR) have demonstrated high prediction accuracy for adsorption energies [17] [18]. Neural networks capture more complex nonlinear relationships but require larger training datasets.

Model Interpretation: Post-hoc analysis with SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) reveals feature contributions and directional trends, connecting ML predictions with physical theories like the d-band and Friedel models [17].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Computational Methods for Adsorption Energy Prediction

| Methodology | Computational Cost | Prediction Accuracy (MAE) | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (BEEF-vdW) | High (days-weeks) | Reference standard | Mechanism validation, electronic analysis |

| Random Forest Regression | Low (minutes-hours) | 0.08-0.15 eV for H/C/O adsorption [17] | High-throughput screening of bimetallics |

| Gaussian Process Regression | Medium | 0.05-0.12 eV for MXenes [18] | Small datasets, uncertainty quantification |

| Symbolic Regression | Medium | N/A (descriptor discovery) | Identifying novel descriptor combinations |

| Neural Networks | High (training) | Variable, improves with data size | Complex systems with large datasets |

Experimental Validation: Bridging Computation and Measurement

Protocol for Experimental Catalyst Testing

Validating computational predictions requires carefully controlled experimental protocols to ensure reliable structure-activity relationships:

Catalyst Synthesis and Characterization: Reproducible synthesis methods (impregnation, co-precipitation, etc.) prepare catalysts with controlled compositions. Characterization techniques including X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) verify structural properties.

Kinetic Measurements: Reactor systems (fixed-bed, batch) measure catalytic performance under controlled temperature, pressure, and flow conditions. Turnover frequency (TOF) calculations normalize activity by the number of active sites, determined through chemisorption or titration methods.

Descriptor Quantification: Temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) experiments measure adsorption strengths experimentally. For example, ammonia TPD profiles can correlate with Lewis acid strength in zeolites [16]. Spectroscopic techniques (IR, XAS) probe electronic and structural properties of active sites.

Case Study: Dehydrogenation on Lewis Acid Zeolites

A comprehensive study on propane dehydrogenation (PDH) over Lewis acid zeolites demonstrates the descriptor-validation workflow [16]. Isolated metal sites (Pt, Cu, Ni, Co, Mn, Pb, Sn) in MFI zeolite frameworks were evaluated using a combination of DFT calculations, microkinetic modeling, and experimental testing. The dissociative adsorption energy of methane (ΔHCH3-H) emerged as an effective descriptor, showing strong correlations with transition state energies for C-H activation [16]. Experimental measurements of PDH rates confirmed the predicted volcano relationship, with Pt- and Cu-containing sites exhibiting the highest activities near the volcano peak [16].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function/Benefit | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP | Software | DFT calculations for periodic systems | Commercial license |

| Catalysis-hub.org | Database | Repository of catalytic reactions and energies | Free access |

| SPOCK | Tool | Automated volcano plot construction and validation | Open-source web application [15] |

| CatDRX | Framework | Reaction-conditioned generative model for catalyst design | Research code [19] |

| BEEF-vdW | Functional | DFT functional with error estimation and vdW corrections | Included in major DFT codes |

| EnhancedVolcano | R Package | Publication-ready volcano plot visualization | Bioconductor [20] |

Integrated Workflow for Descriptor-Based Catalyst Design

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for descriptor-based catalyst design, integrating computational and experimental approaches:

Comparative Analysis of Design Strategies

Traditional DFT-Based Screening vs. ML-Accelerated Approaches

Traditional DFT screening provides fundamental insights into reaction mechanisms and electronic structure but faces scalability limitations. In contrast, ML-accelerated approaches enable rapid exploration of vast chemical spaces but depend on data quality and quantity:

Accuracy vs. Speed Trade-off: DFT calculations offer high accuracy but require substantial computational resources (weeks for screening 50-100 catalysts). ML models predict adsorption energies thousands of times faster with moderate accuracy (MAE ~0.1 eV), sufficient for initial screening [17] [18].

Transferability Domain: DFT methods transfer across different reaction environments, while ML models perform best within their training domain. ML predictions for bilayer MXenes showed reduced accuracy when catalyst structures differed significantly from training data [18].

Interpretability Advantage: DFT provides inherent interpretability through electronic structure analysis, whereas ML models require additional interpretation methods (SHAP, PFI) to extract physical insights [17].

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The field is evolving toward hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both computational and experimental methods:

Multi-fidelity Modeling: Combining high-accuracy DFT with rapid ML predictions creates tiered screening workflows [18].

Reaction-Conditioned Generation: Frameworks like CatDRX incorporate reaction components as conditions for catalyst generation, moving beyond simple property prediction to inverse design [19].

Automated Descriptor Discovery: Tools like SPOCK enable standardized volcano construction and can identify novel descriptor-performance relationships that might challenge human intuition [15].

Experimental Integration: Advanced ML algorithms now incorporate synthetic feasibility constraints and experimental validation feedback loops, bridging the virtual-experimental gap [19].

Descriptor-based design represents a powerful framework for rational catalyst development, with volcano plots serving as intuitive visualizations of catalyst-activity relationships. The integration of computational approaches—from fundamental DFT calculations to modern ML algorithms—with careful experimental validation creates a virtuous cycle for catalyst discovery and optimization. As computational power increases and algorithms become more sophisticated, the future promises even closer integration between theoretical prediction and experimental validation, accelerating the development of catalysts for sustainable energy and chemical processes.

The accelerating climate crisis and rising global energy demands have created an urgent need for the rapid discovery of new, high-performing materials for sustainable electrochemical technologies, including energy storage, green hydrogen production, and carbon capture [21]. Traditional benchtop research and development, which involves proposing, synthesizing, and testing one material at a time, operates on a timescale of months or even years for each new material. This pace is simply insufficient to meet current challenges [21]. High-throughput (HT) workflows offer a transformative solution by significantly accelerating material discovery through the integration of computational screening and automated experimentation. These workflows are designed for the synthesis, characterization, and analysis of dozens to thousands of materials in parallel, drastically compressing development timelines [21] [22]. The core power of these methodologies lies in their integration: by screening millions of material candidates computationally and validating the most promising candidates experimentally, researchers can navigate the vast chemical space of possibilities with unprecedented efficiency [21] [23]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the key components, software platforms, and methodologies that constitute modern, integrated high-throughput workflows, with a specific focus on validating computational catalysis models with experimental data.

Comparative Analysis of High-Throughput Workflow Platforms and Tools

The effectiveness of a high-throughput workflow is heavily dependent on the software and tools that power its computational and data management processes. The table below compares several key platforms and their capabilities.

Table 1: Comparison of High-Throughput Workflow Software and Tools

| Tool/Platform Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Reported Throughput / Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoRW (Schrödinger) | Automated computational reaction workflow | Automates enumeration, mapping, and organization of reaction coordinates; integrated with machine learning [24]. | Enables screening of ~2,000 catalysts per year by a team, compared to ~150 by a single modeler [24]. |

| Katalyst D2D (ACD/Labs) | End-to-end HTE workflow management | Integrates experiment design, data analysis, and AI/ML-powered design of experiments (DoE); reads >150 instrument data formats [25]. | Allows non-expert users to design a 96-well experiment in <5 minutes [25]. |

| HTEM-DB (NREL) | Research data infrastructure | Curates and provides access to high-throughput experimental materials science data via a web interface and API [26]. | Provides a large-scale, high-quality dataset for machine learning in materials science [26]. |

| Workflow Selection Framework [27] | Algorithmic workflow selection | A framework for autonomous systems to select the highest-value data collection workflow based on information quality and cost. | In a case study, reduced image collection time by a factor of 85 compared to a previously published study [27]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput Experimentation

Successful high-throughput experimentation relies on a suite of essential materials and reagents that enable parallelized and automated synthesis and testing.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions in HT Workflows

| Reagent / Material Category | Example Components | Function in High-Throughput Workflows |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Material Libraries | Precious metal catalysts (Pt, Au, Ir), non-precious metal alternatives, metal alloys [21] | Serve as the primary test subjects for discovery and optimization in electrochemical reactions (e.g., water splitting, CO2 reduction) [21]. |

| Polymer & Organic Precursors | Epoxides, amines, donor-acceptor molecules, organic molecular precursors [24] [23] | Used for discovering and optimizing organic materials and polymers for applications in optoelectronics, gas uptake, and catalysis [23]. |

| Stationary Phases for HTA | Sub-2µm fully porous particles (FPPs), superficially porous particles (SPPs or core-shell) [22] | Enable rapid chromatographic separation and analysis, which is critical for generating analytical data in line with HTE synthesis speeds [22]. |

| Electrolytes & Ionomers | Aqueous and non-aqueous electrolytes, ion-conductive polymers [21] | Critical components for electrochemical device performance and durability; a current shortage in HT research exists for these materials [21]. |

Experimental Protocols for Workflow Validation

Validating computational predictions with robust experimental data is the cornerstone of integrated workflows. The following protocols detail standard methodologies for key stages.

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Computational Screening with DFT

This protocol is widely used for the initial, large-scale virtual screening of material candidates [21].

- Descriptor Selection: Choose a quantifiable representation of the property of interest. For electrocatalysts, a common descriptor is the adsorption energy (ΔG) of a reaction intermediate in the rate-limiting step, which connects electronic structure calculations to macroscopic catalytic activity [21].

- First-Principles Calculation: Use Density Functional Theory (DFT) to compute the selected descriptor for each material in the virtual library. The choice of the density functional is critical for balancing accuracy and computational cost [21].

- Database Generation: Compile the calculated descriptors and associated material structures into a searchable database.

- Candidate Identification: Apply filtering criteria (e.g., a threshold for adsorption energy) to the database to identify the most promising candidate materials for experimental synthesis and testing [21].

Protocol 2: Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflow

This protocol describes a closed-loop process that tightly couples computation and experiment for accelerated discovery [21] [23].

- Precursor Selection: Use computational filtering or AI-driven molecular generation to select promising organic molecular precursors from a vast chemical space, moving beyond conservative, known molecules [23].

- Automated Synthesis & Characterization: Employ robotic and automated systems to synthesize thousands of material samples in parallel (e.g., in 96- or 384-well plates) and characterize them using high-throughput analytical techniques [23].

- High-Throughput Analysis (HTA): Analyze the synthesized materials using fast analytical techniques. For example, use Ultrahigh-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) with sub-2µm particles or superficially porous particles to achieve analysis times of a few minutes or less per sample [22].

- Data Integration and Model Validation: Feed the experimental results (e.g., conversion, yield, material properties) back into the computational models. This data is used to validate the initial predictions, refine the models, and identify any discrepancies [23].

- Iterative Loop: Use the refined models to design the next set of experiments, thus closing the loop and creating an iterative, self-improving discovery cycle [21] [23].

Protocol 3: Autonomous Workflow Selection for Characterization

This protocol enables autonomous systems to select optimal data collection workflows, maximizing information value while minimizing time or cost [27].

- Define Objective: Establish a clear, quantifiable objective (e.g., measure grain size, determine defect density) [27].

- List Available Procedures: Catalog all available experimental procedures, methods, and models that could be used in the workflow [27].

- Fast Search: Conduct a fast search over the space of all possible workflows to quickly filter for those that generate high-quality information relevant to the objective [27].

- Fine Search: Perform a detailed evaluation of the high-quality workflows to select the optimal one. The selection is based on a value function that considers both the quality of the information and its actionability for the objective, balanced against the cost of acquisition [27].

- Execute and Iterate: The autonomous system executes the experiments using the selected workflow and assesses if the objective is met. If not, it iterates by returning to Step 3 [27].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, cyclical nature of a modern high-throughput discovery workflow.

Integrated High-Throughput Discovery Workflow

The integration of high-throughput computational and experimental workflows represents a fundamental shift in the paradigm of materials discovery. By leveraging automated computational screening with tools like AutoRW, managing end-to-end experimental data with platforms like Katalyst, and applying rigorous validation protocols, researchers can dramatically accelerate the development of next-generation materials. While challenges remain—such as the need for more HT research on electrolytes and ionomers, and the consideration of cost and safety earlier in the screening process—the continued advancement and integration of these methodologies are critical for addressing pressing global challenges in energy and sustainability [21]. The future points toward increasingly autonomous systems and self-driving models that can not only propose experiments but also dynamically select the most efficient pathways to discovery [27] [28].

The field of computational catalysis has been transformed by advanced modeling and artificial intelligence, enabling the in silico design of novel catalysts. However, the ultimate validation of any computational prediction lies in its experimental confirmation. This guide examines key case studies where computationally designed catalysts were successfully synthesized and tested, providing a critical comparison of the design methodologies, experimental protocols, and resulting performance metrics. The synergy between calculation and experiment is paving the way for a new paradigm in accelerated catalyst discovery [29] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The experimental validation of novel catalysts requires a suite of specialized materials and characterization techniques. The table below details key components and their functions in catalyst synthesis and testing.

Table 1: Key Reagents and Materials in Catalyst Validation

| Item | Function in Catalyst Development |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimental Databases | Provides existing experimental data for model training and validation (e.g., The Materials Genome Initiative) [30]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | A computational method used to calculate electronic structures and predict properties like adsorption energies [29] [31]. |

| Gas Diffusion Layer (GDL) | A conductive substrate used in electrochemical cells (e.g., fuel cells) to support the catalyst and facilitate gas transport [32]. |

| Nafion Solution | A proton-conducting ionomer; used in catalyst inks for fuel cells to create three-phase points for reactions, but excessive use can block active sites [32]. |

| Hexachloroplatinic Acid | A common platinum precursor salt used in the synthesis of platinum-based catalysts [32]. |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | A characterization technique used to confirm the crystal structure and phase purity of synthesized catalyst materials [29]. |

| HAADF-STEM | A high-resolution electron microscopy technique used to visualize atomic structures and confirm the presence of alloyed phases or single atoms [29]. |

Comparative Analysis of Validated Catalyst Designs

The following case studies showcase the successful application of different computational strategies to design catalysts that were subsequently validated through experiment.

Table 2: Case Studies of Experimentally Validated Catalyst Designs

| Catalyst | Target Reaction | Computational Approach | Key Performance Metrics (Experimental) | Experimental Validation Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni₃Mo/MgO [29] | Ethane Dehydrogenation | Descriptor-based screening (C & CH₃ adsorption) and decision mapping. | Ethane conversion: 1.2% (vs. 0.4% for Pt/MgO); Selectivity: 81.2% (after 12h). | Outperformed a standard Pt catalyst in conversion and showed comparable selectivity. |

| RhCu Single-Atom Alloy [29] | Propane Dehydrogenation | Screening based on transition state energy for the initial C-H scission. | More active and stable than Pt/Al₂O³. | Validated the prediction that the catalyst would activate propane like Pt but resist coking. |

| CuAl, AlPd, Sn₂Pd₅, Sn₉Pd₇, CuAlSe₂ [31] | CO₂ Electro-reduction (CO₂RR) | Inverse design via MAGECS framework (Generative AI + Bird Swarm Algorithm). | Two alloys showed ~90% Faraday efficiency and high current densities (-600.6 and -296.2 mA cm⁻² at -1.1 V). | Successfully synthesized five predicted alloys; two showed high activity and selectivity for CO production. |

| PCN-250(Fe₂Mn) MOF [29] | Light Alkane C-H Activation with N₂O | DFT calculations of the N₂O activation barrier. | Activity trend: Fe₂Mn ~ Fe₃ > Fe₂Co > Fe₂Ni (as predicted). | Confirmed the computationally predicted trend in catalytic activity across a series of isostructural MOFs. |

| Pt Catalyst Layer [32] | Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) in PEM Fuel Cells | Mathematical modeling of experimental data to optimize composition. | Highest Electrochemically Active Surface Area (ECSA) at Carbon:Nafion 1:5 ratio (46.839 cm²/g-Pt). | Experimentally identified the optimal composition to balance proton conduction and gas permeability. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

A critical component of validation is a rigorous and reproducible experimental protocol. The methodologies below are adapted from the cited case studies.

Protocol 1: Synthesis and Testing of Alloy Nanoparticle Catalysts

This protocol is typical for catalysts like Ni₃Mo/MgO and Pt₃Ru₁/₂Co₁/₂ [29].

- Catalyst Synthesis: Incipient wetness impregnation or co-precipitation is used to deposit metal precursors onto a support (e.g., MgO, Al₂O₃).

- Calcination & Reduction: The material is calcined in air to decompose precursors and then reduced under H₂ gas at high temperature to form the active alloy nanoparticles.

- Structural Characterization: Techniques including X-ray diffraction (XRD) and High-Angle Annular Dark-Field Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (HAADF-STEM) are employed to confirm alloy formation, particle size, and morphology.

- Reactor Testing: Catalyst performance is evaluated in a fixed-bed flow reactor under relevant conditions (temperature, pressure, feed composition). Product stream is analyzed using gas chromatography (GC) to determine conversion and selectivity.

Protocol 2: Electrochemical Evaluation of CO₂ Reduction Catalysts

This protocol applies to catalysts like the MAGECS-predicted alloys [31].

- Electrode Preparation: The catalyst ink is prepared by dispersing the synthesized catalyst powder (e.g., CuAl alloy) in a solvent with a Nafion binder. The ink is then drop-cast onto a carbon paper or glassy carbon electrode.

- Electrochemical Cell Setup: A standard three-electrode cell is used, with the catalyst as the working electrode, a platinum wire or foil as the counter electrode, and a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl or reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE)).

- Performance Testing: Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) and chronoamperometry are performed in a CO₂-saturated electrolyte. The gas effluent from the cell is analyzed using gas chromatography (GC) to quantify reaction products (e.g., CO, H₂).

- Metric Calculation: Key performance indicators such as Faradaic efficiency (FE %) for each product and the total current density (mA cm⁻²) are calculated from the charge passed and GC data.

Protocol 3: Optimization of Fuel Cell Catalyst Layer

This protocol is derived from the study on Pt/C catalyst layers [32].

- Catalyst Ink Formulation: Pt/C catalyst powder is mixed with a Nafion solution, isopropanol, and deionized water in varying mass ratios (e.g., Carbon:Nafion from 1:3 to 1:7) to create a series of catalyst inks.

- Electrode Fabrication: The inks are sonicated and then coated onto a Gas Diffusion Layer (GDL). The coated electrodes are dried and hot-pressed with a Nafion membrane to create a Membrane Electrode Assembly (MEA).

- Electrochemical Characterization:

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): Conducted in an N₂-saturated electrolyte to determine the Electrochemically Active Surface Area (ECSA).

- Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV): Performed in an O₂-saturated electrolyte at different rotation rates (using a Rotating Disk Electrode) to study the oxygen reduction kinetics and determine the number of electrons transferred.

Workflow Visualization for Computational-Experimental Catalyst Design

The following diagram illustrates the standard iterative pipeline for the computational design and experimental validation of catalysts, integrating common elements from the case studies.

The case studies presented herein demonstrate a powerful consensus: computational models, particularly when guided by robust activity descriptors and advanced generative AI, are capable of directing experimental efforts toward high-performing catalyst candidates. The consistent theme across these success stories is the rigorous experimental validation that closes the design loop, confirming predictive accuracy and providing real-world performance data. As computational power grows and algorithms become more sophisticated, this synergistic cycle of prediction and validation is poised to dramatically accelerate the development of next-generation catalysts for energy and sustainability.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has long served as a cornerstone for computational materials science, enabling researchers to understand and predict material properties at the quantum mechanical level. However, its predictive accuracy is fundamentally limited by systematic errors in exchange-correlation functionals and the significant computational cost of simulating large or complex systems [33] [34]. The emergence of machine learning (ML) has introduced a transformative paradigm, not by replacing DFT, but by augmenting it to create a synergistic partnership that bridges the gap between computational prediction and experimental reality. This combination is particularly valuable in computational catalysis, where validating models against experimental data is essential for developing reliable predictive frameworks.

This guide objectively compares the performance of traditional DFT, standalone ML, and integrated ML-DFT approaches, providing researchers with a clear understanding of their respective capabilities, limitations, and optimal application domains.

Performance Comparison: ML-DFT vs. Traditional Workflows

The integration of ML with DFT typically follows two primary paradigms: (1) using ML to directly predict material properties from DFT-generated data or (2) using ML to create interatomic potentials that dramatically accelerate DFT-level simulations. The table below summarizes the performance advantages of this integrated approach compared to traditional methods.

Table 1: Performance comparison of materials screening approaches

| Method | Accuracy (Typical MAE) | Computational Speed | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|