Catalyst Deactivation and Regeneration: Mechanisms, Models, and Methods for Sustainable Processes

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles, mechanisms, and practical methodologies governing catalyst deactivation and regeneration.

Catalyst Deactivation and Regeneration: Mechanisms, Models, and Methods for Sustainable Processes

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles, mechanisms, and practical methodologies governing catalyst deactivation and regeneration. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the chemical, thermal, and mechanical roots of catalyst decay, including poisoning, fouling, and sintering. The scope extends to established and emerging mathematical models for predicting deactivation, a detailed analysis of regeneration techniques like thermal and chemical treatment, and data-driven strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with applied case studies and future perspectives, this resource aims to equip professionals with the insights needed to enhance catalyst longevity, efficiency, and sustainability in industrial and biomedical applications.

Understanding Catalyst Deactivation: The Root Causes and Underlying Mechanisms

Catalyst deactivation, the irreversible loss of activity and/or selectivity over time, represents a fundamental challenge confronting industrial catalytic processes. This phenomenon transcends specific industries, impacting applications ranging from petroleum refining and chemical synthesis to emerging sustainable technologies for biomass conversion and emission control [1] [2]. The economic implications are profound, with costs for catalyst replacement, process shutdown, and lost production totaling billions of dollars annually [3] [2]. A comprehensive understanding of deactivation mechanisms is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a critical prerequisite for designing more durable catalytic systems, optimizing process economics, and enhancing the sustainability of chemical manufacturing [4].

The stability of a catalyst is as crucial a performance metric as its activity and selectivity [5]. Deactivation is inevitable, yet its timescale varies dramatically—from seconds in fluidized catalytic cracking to years in ammonia synthesis [3] [6] [2]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of catalyst deactivation, detailing its primary mechanisms, methodical approaches for its investigation, and the foundational principles for its mitigation, framed within the broader context of ongoing research aimed at extending functional catalyst lifespans.

Defining Catalyst Activity and Deactivation

In formal terms, the activity of a catalyst at any given time ( t ) is defined as the ratio of the reaction rate at that time to the reaction rate observed with the fresh catalyst at the start of operation [6] [2]. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

[ a(t) = \frac{r(t)}{r(t=0)} ]

where ( a(t) ) is the dimensionless activity at time ( t ), ( r(t) ) is the reaction rate at time ( t ), and ( r(t=0) ) is the initial reaction rate. Catalyst deactivation is the process whereby ( a(t) ) decreases from its initial value of 1.0 over time-on-stream (TOS) [6]. This loss of activity is often accompanied by a decline in selectivity, leading to increased production of undesired by-products and further reducing process efficiency [2] [4].

It is paramount to recognize that while a catalyst increases the rate at which a reaction approaches thermodynamic equilibrium, it does not alter the position of that equilibrium [7]. Consequently, a catalyst accelerates both the forward and reverse reactions to the same extent. Deactivation, therefore, is a kinetic phenomenon, stemming from physical and chemical changes to the catalyst itself that reduce its ability to accelerate the target reaction(s).

Principal Mechanisms of Catalyst Deactivation

Catalyst deactivation arises from complex chemical and physical processes. These mechanisms are often categorized into three primary types: chemical, thermal, and mechanical deactivation [2] [8]. In practice, multiple mechanisms can occur simultaneously or synergistically, complicating diagnosis and mitigation [1] [4].

Chemical Deactivation: Poisoning and Fouling

Chemical deactivation involves the strong chemical interaction of foreign substances with the catalyst's active sites.

Poisoning: This occurs when impurities in the feed stream chemisorb strongly to active sites, rendering them unavailable for the intended catalytic reaction [2] [8]. Poisons are highly specific to the catalyst material. Common poisons include:

- Sulfur compounds (e.g., H₂S): Severe poisons for Group VIII metals like nickel used in steam reforming and other processes [1] [2].

- Alkali and Alkaline Earth Metals (AAEMs) (e.g., potassium, sodium): Can poison acid sites on catalysts used in biomass conversion [1] [5].

- Heavy Metals (e.g., lead, arsenic, mercury): Poisons for numerous metal catalysts [2] [8]. Poisoning can be reversible or irreversible, depending on the strength of the adsorbate-catalyst bond and the operating conditions [5] [2].

Coking/Fouling: This is the physical deposition of carbonaceous material (coke) or other substances from the reaction stream onto the catalyst surface and within its pores [1] [3]. Coke formation is particularly prevalent in reactions involving hydrocarbons at elevated temperatures [3] [4]. The deposits physically block active sites and impede the diffusion of reactants and products, leading to activity loss [1]. The nature of coke—ranging from soft, hydrogen-rich deposits to hard, graphitic carbon—depends on the reaction conditions and catalyst properties [3].

Thermal Deactivation: Sintering

Thermal degradation, primarily sintering, is the loss of active surface area due to exposure to high temperatures, often exacerbated by the presence of water vapor [1] [8]. Sintering is a thermodynamically driven process where small, high-surface-energy catalyst particles agglomerate into larger, more stable particles with lower total surface area [2] [4]. This process is largely irreversible and diminishes activity, especially for catalysts where activity is proportional to surface area, such as supported metals [1] [8]. The rate of sintering increases exponentially with temperature.

Mechanical Deactivation: Attrition and Crushing

Mechanical deactivation involves the physical breakdown of catalyst particles [2]. Attrition is the wearing down of particles due to collisions in fluidized or slurry-bed reactors, leading to fine powder that can be elutriated from the system [1]. Crushing is the mechanical failure of catalyst pellets under the weight of the catalyst bed or due to thermal stresses in fixed-bed reactors, which can cause a high pressure drop and channeling [2] [8].

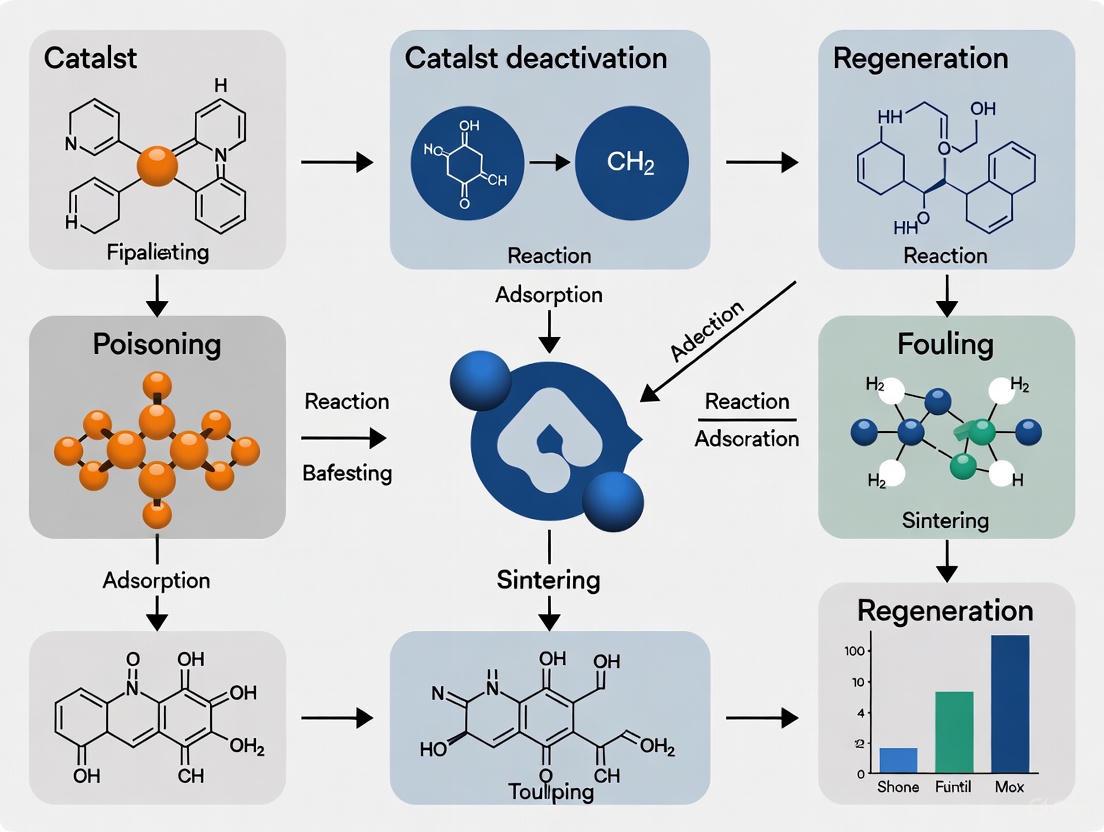

The following diagram illustrates the primary deactivation mechanisms and their direct impacts on the catalyst structure.

Diagram 1: Primary catalyst deactivation mechanisms and their direct effects.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Catalyst Deactivation Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Primary Cause | Key Characteristics | Industrially Relevant Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poisoning | Strong chemisorption of impurities on active sites [2] [8]. | Often specific to catalyst/poison pair; can be reversible or irreversible [5] [2]. | S poisoning of Ni reforming catalysts [2]; K poisoning of Pt/TiO₂ in biomass pyrolysis [5]. |

| Coking/Fouling | Deposition of carbonaceous species from reaction stream [1] [3]. | Can block sites and pores; often reversible via combustion [3]; prevalent in hydrocarbon processing [4]. | Coke formation in FCC catalysts [3] [6]; carbon deposition in FTS [1]. |

| Sintering | Exposure to high temperature (and water vapor) [1] [8]. | Irreversible loss of active surface area; agglomeration of metal particles [2] [4]. | Sintering of Co and Fe particles in Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis [1]. |

| Attrition/Crushing | Mechanical stress (collisions, bed weight, thermal stress) [2] [8]. | Physical breakdown of catalyst particles; increased pressure drop; catalyst loss [1] [8]. | Attrition in fluidized-bed Fischer-Tropsch reactors [1]. |

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Deactivation

A methodical approach combining activity testing with advanced characterization is essential to identify the root cause of deactivation [8]. The following workflow outlines a standard investigative protocol.

Diagram 2: Root cause analysis workflow for catalyst deactivation.

Core Activity and Deactivation Kinetics Measurement

The foundation of deactivation studies is the measurement of catalyst activity as a function of time-on-stream (TOS). Experiments are conducted in laboratory-scale reactors (e.g., fixed-bed, slurry-bed) under controlled conditions mimicking industrial operation [6]. The data collected is used to fit deactivation models.

- Time-on-Stream (TOS) Models: Empirical models correlate activity directly with time. The simplest is the power-law model: ( a(t) = A \cdot t^{n} ), where ( A ) and ( n ) are constants [6]. Another common form is the exponential model: ( a(t) = e^{-kd \cdot t} ), where ( kd ) is the deactivation rate constant [6].

- Coke-Dependent Models: For coking catalysts, activity is often linked to coke content ( Cc ), e.g., ( a(t) = \frac{1}{(1 + \alpha \cdot Cc)^{m}} ) [6].

Essential Characterization Techniques

A suite of characterization techniques is employed to probe the physical and chemical changes in the deactivated catalyst.

Table 2: Key Characterization Techniques for Catalyst Deactivation Analysis

| Technique | Acronym | Primary Function in Deactivation Analysis | Key Measurable Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| N₂ Physisorption | BET | Quantifies textural changes [8]. | Surface area, pore volume, pore size distribution. Loss indicates sintering/fouling [8]. |

| X-Ray Fluorescence | XRF | Identifies and quantifies elemental composition of bulk impurities [8]. | Concentration of poisons (S, P, K, heavy metals) on the catalyst [8]. |

| X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy | XPS | Determines elemental composition and chemical state at the surface [4] [8]. | Surface concentration of poisons, oxidation states of active metals, presence of coke. |

| Temperature-Programmed Desorption/Reduction/Oxidation | TPD/TPR/TPO | Probes surface properties and reactivity [8]. | TPD: Active site strength and density. TPO: Nature and quantity of coke deposits [3]. |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis | TGA | Measures weight changes as a function of temperature [4]. | Quantifies coke burn-off (in air/O₂) or metal reduction (in H₂). |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy | TEM/STEM | Provides direct imaging of catalyst nanostructure [4]. | Metal particle size distribution (sintering), location of coke, and mapping of elements. |

| X-Ray Diffraction | XRD | Assesses crystallographic structure [4]. | Crystallite size (sintering), phase changes (e.g., oxidation, carbide formation). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

- High-Purity Gases (H₂, O₂, He, N₂): Used as reactants, purge gases, and analysis carriers in TPD/TPR/TPO experiments to avoid introducing contaminants [8].

- Model Poison Compounds (e.g., Thiophene, PH₃): Well-defined chemicals used in controlled dosing experiments to simulate feedstock impurities and study poisoning mechanisms [2].

- Calibration Standards for Elemental Analysis (XRF, XPS): Certified reference materials essential for accurate quantification of elemental composition in fresh and spent catalysts [8].

- Oxidizing Agents (e.g., O₂, O₃, NO₂): Used in TPO and regeneration studies to selectively remove coke deposits from catalyst surfaces [3].

- Catalyst Supports (e.g., Al₂O₃, SiO₂, TiO₂, Zeolites): High-surface-area materials that act as scaffolds for active metal phases; their acidity, porosity, and metal-support interactions critically influence deactivation resistance [1] [5].

Foundational Mitigation and Regeneration Strategies

Addressing catalyst deactivation requires a holistic strategy encompassing catalyst design, process engineering, and regeneration protocols.

- Catalyst Design and Selection: Designing catalysts with inherent resistance is the first line of defense. This includes using supports with strong metal-support interactions to inhibit sintering [4], tailoring pore architectures to reduce coke formation and pore blockage [1], and incorporating guard components that sacrificially adsorb poisons [2] [8].

- Process Condition Optimization: Careful control of operating parameters can significantly extend catalyst life. This involves:

- Feedstock Purification: Using guard beds (e.g., ZnO for sulfur removal) or catalytic pretreatments to reduce poison levels in the feed [2].

- Temperature Management: Operating at the lowest feasible temperature to minimize sintering and coking rates. Using dilution or multi-stage reactors can manage exotherms [8].

- Optimized Feed Composition: Adjusting ratios like H₂/CO in Fischer-Tropsch or steam/hydrocarbon in reforming to thermodynamically suppress coking [1].

- Regeneration Techniques: When deactivation occurs, regeneration is key.

- Oxidative Regeneration: The most common method for coke removal, involving controlled combustion with air or O₂. The major challenge is managing exotherms to prevent thermal damage [3].

- Chemical Treatment: Washing with solvents or complexing agents to remove specific poisons (e.g., water washing to remove potassium) [5].

- Reductive Regeneration: Treatment with H₂ at high temperature to remove sulfur poisons (for some catalysts) or reduce oxidized active phases [3] [2].

Catalyst deactivation is an inescapable challenge that fundamentally impacts the efficiency, economics, and sustainability of industrial chemical processes. A deep understanding of its core mechanisms—poisoning, coking, sintering, and attrition—provides the essential framework for diagnosing and combating this phenomenon. Through a rigorous, methodology-driven approach that integrates kinetic modeling with advanced characterization, researchers can pinpoint root causes. This knowledge, in turn, enables the rational design of more robust catalysts and the development of optimized processes and regeneration protocols. As industrial catalysis increasingly pivots to meet the demands of a sustainable economy, including the processing of complex biomass-derived feeds and CO₂ utilization, the principles governing catalyst deactivation and stability will only grow in importance, forming a critical pillar of catalysis research for years to come.

Catalyst deactivation, the loss of activity and/or selectivity over time, is a fundamental challenge that impacts the economic and operational viability of industrial catalytic processes. The development of mitigation and regeneration strategies hinges on a systematic understanding of the underlying decay mechanisms. Within the broader context of catalyst deactivation and regeneration research, this whitepaper provides a structured classification of the six intrinsic mechanisms of catalyst decay. By integrating contemporary research and established industrial knowledge, this guide serves as a technical resource for researchers and scientists aiming to design more robust and durable catalytic systems.

The imperative for such a classification is underscored by the significant costs associated with catalyst replacement and process shutdowns, which can total billions of dollars annually [2]. The time scales of deactivation vary dramatically, from seconds for fluid catalytic cracking catalysts to over a decade for catalysts used in ammonia synthesis, yet decay remains an inevitable process [2]. A precise understanding of these mechanisms is the first step in delaying the inevitable and enhancing catalytic longevity, which is a central thesis in sustainable process design.

A Systematic Classification of Decay Mechanisms

Catalyst deactivation mechanisms can be systematically categorized into six primary intrinsic pathways. These are distinct yet can occur simultaneously or synergistically during operation, leading to a complex interplay that accelerates activity loss. The table below summarizes these core mechanisms, their fundamental causes, and representative chemical processes where they are prevalent.

Table 1: The Six Intrinsic Mechanisms of Catalyst Decay

| Mechanism | Fundamental Cause | Representative Industrial Process |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Poisoning | Strong chemisorption of impurities onto active sites, blocking reactant access. | Ammonia Synthesis, Steam Reforming [2] |

| 2. Coking & Fouling | Physical deposition of carbonaceous species (coke) or other inert materials on active sites and pores. | Fluid Catalytic Cracking, Biomass/Biomass and Solid Waste Gasification [3] [9] |

| 3. Thermal Degradation (Sintering) | Thermally-induced loss of active surface area via crystal growth (Ostwald ripening) or particle migration. | Steam Reforming, Exhaust Gas Treatment [2] |

| 4. Vapor Compound Formation & Transport | Formation of volatile chemical compounds that remove the active phase from the catalyst. | Methanation (via Metal Carbonyls) [2] |

| 5. Mechanical Damage | Physical loss of catalyst integrity through crushing, attrition, or erosion. | Processes with High Fluid Velocity or Pressure Drops [2] |

| 6. Chemical & Phase Transformation | Solid-state reactions leading to undesirable phase changes or loss of critical structural properties. | High-Temperature Oxidation/Reduction Catalysis [10] |

Detailed Mechanism Analysis and Experimental Protocols

Poisoning

Poisoning occurs when a chemical impurity in the feed stream strongly and preferentially chemisorbs onto the catalyst's active sites, rendering them inaccessible for the intended reaction. The strength of this interaction is often electronic, involving the d-orbitals of transition metal catalysts [2].

- Key Poisons: For metal catalysts, poisons are typically classified into nonmetallic ions (e.g., H₂S, PH₃, AsH₃), certain metal ions (e.g., Hg²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺), and unsaturated molecules that adsorb irreversibly (e.g., CO) [2].

- Experimental Protocol for Poisoning Study:

- Catalyst Testing: Conduct a catalytic reaction (e.g., steam reforming) in a fixed-bed reactor with a carefully controlled feed containing a trace, quantified amount of the suspected poison (e.g., H₂S).

- Activity Monitoring: Measure the reaction rate constant or conversion as a function of time-on-stream and compare it to a baseline test with a pure feed.

- Post-Reaction Characterization:

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Used to identify the chemical state of the poison on the catalyst surface (e.g., confirming sulfide species on a poisoned Ni catalyst) [11].

- Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD): Can determine the binding strength of the poison to the active sites by measuring the temperature required for its desorption.

- Regeneration Test: Assess reversibility by treating the poisoned catalyst with a regenerant (e.g., hydrogen at elevated temperature) and re-evaluating its activity.

Coking and Fouling

Coke deposition is the most common form of deactivation in processes involving organic compounds, such as in petrochemicals and biomass conversion [3] [9] [2]. It involves the formation of carbonaceous deposits that physically block active sites and pores.

- Coke Classification: Coke can be categorized as (i) encapsulating carbon, which coats metal particles; (ii) filamentous carbon, which grows as carbon nanotubes/nanofibers, potentially disrupting the physical catalyst structure; and (iii) pyrolytic carbon, formed at high temperatures via direct cracking [9].

- Experimental Protocol for Coking Analysis:

- Accelerated Coking Experiment: Perform the target reaction (e.g., toluene steam reforming) under conditions known to promote coking, such as lower steam-to-carbon ratios [9].

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): The coked catalyst is subjected to TGA in an air atmosphere. The mass loss profile during temperature ramping quantifies the amount of coke and can provide information on its reactivity/burn-off temperature [9].

- Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM): Used to visualize the morphology of the coke, distinguishing between encapsulating layers and filamentous structures [9].

- Spectroscopic Characterization: Raman spectroscopy can determine the graphitic degree of the carbon deposits, which relates to their stability and difficulty of removal.

Thermal Degradation (Sintering)

Sintering is the thermodynamically driven growth of small catalyst particles or crystallites into larger ones, resulting in a decrease in active surface area. This process becomes significant at temperatures above the Tammann temperature of the active phase [9].

- Mechanisms: Sintering proceeds via two primary pathways: (i) Particle Migration and Coalescence, where entire crystallites migrate and fuse upon contact; and (ii) Ostwald Ripening, where atomic or molecular species detach from smaller particles and diffuse to larger ones [9].

- Experimental Protocol for Sintering Assessment:

- Accelerated Aging: Subject the fresh catalyst to a high-temperature treatment (e.g., in air or inert atmosphere) for a set duration.

- Surface Area Measurement: Use Physisorption (BET method) to track the reduction in total surface area.

- Crystallite Size Analysis: Employ X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to measure the average crystallite size of the active metal (e.g., Ni) using the Scherrer equation. An increase in size indicates sintering.

- Direct Imaging: Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) provides direct visual evidence of particle growth and can help distinguish between the two sintering mechanisms.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and experimental characterization pathways for the primary deactivation mechanisms.

Diagram 1: Deactivation mechanisms and characterization techniques.

Vapor Compound Formation and Transport

This mechanism involves the chemical reaction of the active catalytic phase to form a volatile compound that is subsequently removed from the catalyst body by the gas flow. A classic example is the formation of volatile nickel carbonyl (Ni(CO)₄) in methanation reactors operating at low temperatures in the presence of CO, which leads to the physical loss of the active nickel metal [2].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Long-Term Stability Testing: Run the catalyst under simulated industrial conditions, including temperature and pressure cycles.

- Analysis of Effluent Stream: Use sensitive analytical techniques like Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) analysis of trapped effluent to detect and quantify the vaporized metal species.

- Post-Run Catalyst Analysis: Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry (AAS) or ICP analysis of the spent catalyst can reveal a measurable loss of the active metal from the catalyst bed [11].

Mechanical Damage

Mechanical failure manifests as catalyst crushing (loss of mechanical strength), attrition (wearing down of particles), or erosion. This leads to an increased pressure drop across a fixed-bed reactor or loss of catalyst from a fluidized bed [2].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Crush Strength Testing: Measure the force required to crush a fresh catalyst pellet using a mechanical press. This establishes a baseline.

- Accelerated Attrition Testing: Subject catalyst particles to a high-velocity gas stream or mechanical stirring in a standardized test apparatus (e.g., a jet-cup attrition tester).

- Post-Test Analysis: Sieve the catalyst after testing to determine the percentage of fines generated. Compare the crush strength of aged catalyst pellets to fresh ones.

Chemical and Phase Transformation

This encompasses solid-state reactions or reconstructions that alter the catalyst's active or supportive phase. For example, in catalytic oxidation, metastable phases engineered for high activity may transform into more stable, less active crystalline structures under operational conditions [10]. Recent research on two-dimensional LaNiO₃ perovskites highlights how microwave shock can be used to create unconventional cubic phases for superior urea oxidation activity, implying that reversion to stable phases is a potential deactivation route [10].

- Experimental Protocol:

- In Situ/Operando Characterization: Use in situ X-ray Diffraction (XRD) or XPS to monitor the catalyst's crystal structure and surface chemistry in real-time under reaction conditions.

- Stability Testing: Expose the catalyst to prolonged reaction conditions or thermal treatments.

- Post-Reaction Analysis: Compare the XRD patterns and XPS spectra of the spent catalyst with the fresh material to identify new, stable, but inactive phases that have formed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, materials, and characterization tools essential for studying catalyst deactivation, as derived from the featured research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Deactivation Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function & Application in Deactivation Research |

|---|---|

| Transition Metal Precursors (e.g., Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O [12]) | Source of active metal for catalyst synthesis, used in precipitation methods to create model catalysts for deactivation studies. |

| Precious Metal Catalysts (e.g., Rh, Pt [9]) | High-activity, often more coke-resistant catalysts; used as benchmarks to understand deactivation mechanisms in severe conditions. |

| MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ) [10] | A two-dimensional conductive support material; studied for its role in enhancing stability and mitigating coke formation in fiber-based sensors and catalysts. |

| Zeolites (e.g., ZSM-5) [3] | Microporous aluminosilicate catalysts/supports; model systems for studying deactivation by coking and regeneration via oxidation with O₂ or O₃. |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) [9] | A key instrument for quantifying the amount of coke deposited on a catalyst by measuring mass loss during controlled combustion. |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer (XPS) [11] | Surface-sensitive technique used to identify the chemical states of elements on the catalyst surface, crucial for detecting poisons (e.g., sulfides) and oxidation states. |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Spectrometer [11] | An analytical technique for detecting trace levels of metals, used to confirm metal loss from catalysts via vapor transport mechanisms. |

Quantitative Data on Deactivation and Regeneration

The economic and operational impact of deactivation necessitates quantitative data for lifecycle analysis and process optimization. The following table consolidates key metrics related to catalyst decay and recovery.

Table 3: Quantitative Metrics in Catalyst Deactivation and Regeneration

| Metric | Data / Value | Context & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Lifespan (Ammonia Synthesis) | 5–10 years [2] | Illustrates the potential for long-term stability in well-controlled, thermodynamically favorable processes. |

| Catalyst Lifespan (Steam Reforming) | 5–6 years (modern catalysts) [2] | Highlights improvements in catalyst design (e.g., coke resistance, mechanical strength) that have extended operational life. |

| Capacitance Retention (Stable Catalyst) | 97.35% after 10,000 cycles [10] | A measure of stability in functional materials (e.g., for flexible energy storage), indicating excellent resistance to mechanical and electrochemical degradation. |

| Regeneration Efficiency (Ozone vs. Air) | Effective at lower temperatures [3] | Advanced regeneration methods like ozone treatment can remove coke more efficiently and with less thermal damage to the catalyst than conventional air combustion. |

| Sintering Onset | Above Tammann Temperature [9] | The Tammann temperature (approx. 0.5 × melting point in Kelvin) is a critical threshold for the onset of significant thermal sintering. |

| Industry Cost of Deactivation | Billions of USD/year [2] | underscores the massive economic driver behind fundamental and applied research into deactivation mechanisms and regeneration technologies. |

The systematic classification of catalyst decay into six intrinsic mechanisms—poisoning, coking, thermal degradation, vapor transport, mechanical damage, and chemical transformation—provides a foundational framework for both academic research and industrial practice. As catalytic processes become increasingly critical for a sustainable chemical industry, energy conversion, and environmental protection, a deep understanding of these deactivation pathways is more vital than ever. Current research frontiers, including the use of microwave thermal engineering to stabilize unconventional phases [10] and machine learning to predict catalyst lifetime [13] [12], are poised to transform our ability to design catalysts that are not only highly active but also intrinsically resistant to decay. The continued refinement of this systematic understanding, integrated with advanced materials design and intelligent process control, will form the cornerstone of next-generation catalytic technologies with extended service life and enhanced economic and environmental performance.

Catalyst deactivation is a critical challenge that impacts the economic viability and operational stability of industrial chemical processes, including those in pharmaceutical development [14]. Among the various deactivation pathways, poisoning and inactivation via chemical reactions represent some of the most chemically complex and detrimental mechanisms. These processes involve the irreversible or strongly reversible chemical interaction of contaminants with active sites, leading to permanent activity loss [8]. Within the broader thesis of catalyst deactivation and regeneration research, understanding these molecular-level chemical interactions is paramount for developing poisoning-resistant catalysts and extending catalytic lifetime in drug synthesis and other fine chemical productions [5]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the fundamental chemical mechanisms, experimental characterization methodologies, and computational modeling approaches relevant to researcher and scientist workflows in catalytic reaction engineering.

Fundamental Chemical Mechanisms of Catalyst Poisoning

Catalyst poisoning occurs when impurities present in reactant streams form strong chemical bonds with active sites, rendering them inaccessible for the intended catalytic reaction [14] [8]. The strength and nature of these chemical interactions determine whether poisoning is reversible or irreversible under process conditions.

Molecular-Level Interaction Mechanisms

Chemisorption Blocking: Poisoning molecules competitively and strongly adsorb to active sites, physically blocking reactant access. Unlike reversible inhibition, poisoning involves strong covalent or ionic bonding that cannot be reversed simply by removing the poison from the feed stream [14]. The effectiveness of a poison depends on its electron density, molecular geometry, and strength of surface complex formation.

Electronic Structure Modification: Certain poisons alter the electronic properties of catalytic sites through ligand effects. For example, electronegative elements like chlorine or sulfur can withdraw electron density from metal centers, modifying their adsorption properties and reducing their ability to activate reactants [8].

Selective Site Poisoning: In multifunctional catalysts, poisons may selectively target specific site types. Research on Pt/TiO₂ catalysts used in catalytic fast pyrolysis demonstrated that potassium preferentially poisons Lewis acid Ti sites both on the support and at the metal-support interface, while metallic Pt clusters remain largely uncontaminated [5].

Chemical Compound Formation: Some poisons react with active components to form new, inactive chemical compounds. For instance, vanadium species in heavy feeds can react with catalyst supports to form low-melting-point vanadates that destroy pore structure and active sites [15].

Common Catalytic Poisons and Their Origins

Table 1: Common Catalyst Poisons and Their Chemical Sources

| Poison Category | Specific Poisons | Typical Sources | Primary Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic Poisons | Mercury, Lead, Arsenic | Contaminated feedstocks, impurities | Amalgamation, strong chemisorption, site blocking [8] |

| Non-Metallic Poisons | Sulfur, Chlorine, Silicon | Feed impurities, process additives | Strong covalent bonding, electronic effects [8] |

| Alkali & Alkaline Earth Metals | Potassium, Sodium | Biomass feedstocks, contaminants | Neutralization of acid sites, site blocking [5] |

| Heavy Metals | Vanadium, Nickel | Heavy petroleum fractions, residues | Pore blockage, compound formation, site destruction [15] |

Experimental Methodologies for Poisoning Mechanism Analysis

Understanding poisoning mechanisms requires sophisticated characterization techniques that can identify the chemical state and spatial distribution of poisons on catalyst surfaces.

Catalyst Characterization Techniques

Surface Spectroscopy Methods: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) provides information about the chemical state and composition of the top 1-10 nm of catalyst surfaces, enabling identification of poison oxidation states and bonding environments [8]. This technique can distinguish between different sulfur species (sulfide, sulfate) or determine whether potassium is present as metallic, oxide, or hydroxide forms.

Temperature-Programmed Techniques: Temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) measures the strength of adsorption between poisons and catalyst surfaces by monitoring desorption as a function of temperature [8]. Stronger poison-catalyst interactions result in higher desorption temperatures, providing insights into reversibility and binding energy.

Elemental Analysis Methods: X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and proton-induced X-ray emission (PIXE) provide quantitative analysis of poison elements deposited on catalyst surfaces, even at trace concentrations [8]. These techniques are particularly valuable for mapping poison distribution across catalyst particles.

Surface Area and Porosity Analysis: BET surface area analysis measures reductions in accessible surface area resulting from poison deposition, helping distinguish between uniform monolayer coverage and pore blockage mechanisms [8].

Accelerated Deactivation Testing Protocols

Industrial catalyst lifetimes often extend to years, making real-time deactivation studies impractical. Accelerated deactivation methodologies subject catalysts to extreme conditions or highly contaminated feeds to simulate long-term poisoning in condensed timeframes [15].

High-Severity Testing: Exposure to elevated temperatures accelerates thermodynamic processes like sintering and can promote poison-catalyst interactions. However, excessively high temperatures may introduce deactivation mechanisms not representative of actual operating conditions [15].

Concentrated Poison Exposure: Using feeds artificially enriched with potential poisons (e.g., potassium-doped biomass, sulfur-spiked hydrocarbons) accelerates poisoning while maintaining chemical relevance. This approach successfully predicted potassium poisoning in Pt/TiO₂ catalysts for biomass conversion [5].

Protocol Validation: Accelerated methods must be validated against industrially deactivated catalysts to ensure they reproduce the same chemical states, spatial distributions, and structural changes observed in practice [15].

Quantitative Modeling of Catalyst Deactivation Kinetics

Mathematical modeling of deactivation kinetics is essential for predicting catalyst lifetime and optimizing regeneration strategies. Deactivation models generally correlate catalyst activity with time-on-stream, poison concentration, or operating conditions [6].

Fundamental Deactivation Rate Equations

The activity of a catalyst at any time ( t ) is defined as the ratio of its current reaction rate to its initial rate:

[ a(t) = \frac{r(t)}{r(t=0)} ]

The rate of deactivation is typically expressed as a power-law function:

[ -\frac{da}{dt} = k_d \cdot a^n ]

where ( k_d ) is the deactivation rate constant and ( n ) is the order of deactivation [6].

Classification of Deactivation Kinetic Models

Table 2: Mathematical Models for Catalyst Deactivation Kinetics

| Model Type | Mathematical Form | Applicability | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Based Models | ( a(t) = A \cdot t^n ) [6] | Fluid catalytic cracking, rapid deactivation systems | A, n (empirical constants) |

| Exponential Decay Models | ( a(t) = e^{-k_d \cdot t} ) [6] | Hydrotreating, hydrocarbon processing | kd (deactivation rate constant) |

| Generalized Power Law with Residual Activity | ( a(t) = a{\infty} + (1 - a{\infty}) \cdot e^{-k_d \cdot t} ) [6] | Fischer-Tropsch, systems with stable residual activity | kd, a∞ (residual activity) |

| Selective Deactivation Models | ( ai(t) = f(Cj, t) ) for component i [6] | Multi-component reaction systems | Component-specific rate constants |

Mitigation Strategies for Catalyst Poisoning

Process-Based Mitigation Approaches

Feedstock Purification: Implementing guard beds, adsorbents, or pretreatment stages to remove potential poisons before they contact the primary catalyst. For example, chloride guards can protect sensitive catalysts in pharmaceutical processes [8].

Operational Modifications: Adjusting temperature, pressure, or space velocity to minimize poison adsorption while maintaining target conversion levels. In some cases, dilution air can moderate temperatures and reduce poisoning rates [8].

Catalyst Formulation Design: Developing catalysts with increased poison tolerance through promoters or modifiers that block poison adsorption sites while maintaining activity for target reactions [5].

Regeneration of Poisoned Catalysts

Chemical Washing: Water washing successfully reversed potassium poisoning on Pt/TiO₂ catalysts by dissolving and removing potassium deposits [5]. Acid or base washes may be employed for other poison types.

Oxidative Regeneration: Burning carbonaceous deposits can restore activity when poisons are associated with coke layers, though this approach is ineffective for metallic poisons strongly bonded to catalyst surfaces [14].

Research Reagent Solutions for Poisoning Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Catalyst Poisoning Investigations

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Model Poison Compounds | Controlled introduction of specific poisoning elements | Potassium salts for biomass catalyst studies, thiophenes for sulfur poisoning [5] |

| Standard Reference Catalysts | Baseline for deactivation comparison | Pt/TiO₂ for acid site poisoning studies, CoMo/γ-Al₂O₃ for hydrotreating [5] [15] |

| Surface Characterization Standards | Calibration of analytical equipment | XPS reference samples with known surface concentrations [8] |

| Guard Bed Adsorbents | Poison removal studies | Zinc oxide for sulfur removal, alumina for chloride capture [8] |

| Regeneration Reagents | Reactivation of poisoned catalysts | Dilute acids for metal removal, oxidative solutions for carbon removal [5] |

Visualizing Catalyst Poisoning Mechanisms and Experimental Workflows

Figure 1: Chemical Poisoning Mechanism and Investigation Workflow

Figure 2: Accelerated Deactivation Study Protocol

Catalyst deactivation presents a fundamental challenge in industrial catalysis, compromising process efficiency, sustainability, and economic viability. Among various deactivation pathways, mechanical mechanisms—including fouling, coking, and attrition—represent predominant causes of activity loss across numerous chemical processes. These phenomena occur through physical deposition or structural degradation that blocks active sites or compromises catalyst integrity. Within the broader context of catalyst deactivation and regeneration research, understanding these mechanical mechanisms is crucial for developing robust catalytic systems and effective regeneration protocols. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical examination of fouling, coking, and attrition, integrating recent scientific advancements with practical methodologies for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in catalyst design and optimization.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Catalyst Deactivation

Catalyst deactivation encompasses multiple pathways that can be broadly categorized as chemical, thermal, or mechanical in nature. Figure 1 illustrates the primary relationships between these deactivation mechanisms.

Figure 1. Catalyst Deactivation Mechanisms. This diagram categorizes the primary pathways leading to catalyst activity loss, highlighting the position of mechanical mechanisms within the broader deactivation landscape.

While thermal degradation and poisoning are typically slow and often irreversible processes, mechanical deactivation via fouling and coking can occur rapidly but is frequently reversible through appropriate regeneration protocols [6]. The timescale for deactivation varies significantly across processes, from seconds in fluidized catalytic cracking (FCC) to several years in ammonia synthesis [3] [16].

Mechanical Deactivation Pathways

Coking

Coking represents a predominant mechanical deactivation mechanism in processes involving organic compounds and heterogeneous catalysts, particularly in petrochemical operations and biomass conversion [3] [17].

Formation Mechanisms

Coke formation proceeds through three well-established stages: (1) hydrogen transfer at acidic sites, (2) dehydrogenation of adsorbed hydrocarbons, and (3) gas-phase polycondensation [3] [16]. The specific type of coke generated depends on both catalyst characteristics and reaction parameters, with formation rates influenced by temperature, pressure, and feedstock composition.

Coke affects catalyst performance through two primary pathways: active site poisoning via overcoating of catalytic centers and pore blockage that renders active sites inaccessible to reactants [3] [16]. The morphological properties of coke deposits—including their location, composition, and structure—significantly influence regeneration strategies and potential for activity recovery.

Industrial Context: Fluid Catalytic Cracking

In fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) units, coke formation occurs rapidly during the cracking of hydrocarbon feeds at elevated temperatures (approximately 900°F, 482°C) [18]. The coke coats the catalyst surface, preventing access to active sites and necessitating continuous regeneration. FCC designs typically incorporate dedicated regeneration chambers where coke is burned from the catalyst surface with air before the reactivated catalyst returns to the reaction zone [18]. This continuous regeneration cycle is essential for maintaining catalytic activity in rapid coking environments.

Fouling

Fouling encompasses the physical deposition of foreign materials—such as inorganic scales, corrosion products, catalyst fines, and miscellaneous debris—on catalyst surfaces or within reactor components.

Fouling Manifestations in Industrial Systems

In catalytic cracking units, operational deposits typically comprise mixtures of organic and inorganic materials including iron, sulfates, and sulfides [18]. These deposits range in consistency from hard, coke-like materials to sludge-like substances. Common fouling locations include heat exchanger bundles in cycle oil lines, feed stream pre-heat furnaces, and fractionation columns [18].

The presence of unsaturated compounds (alkenes) formed during catalytic reactions can lead to deposition of low-molecular weight polymers and varnish within fractionators and associated heat exchange equipment [18]. Additionally, specialized vessels such as slurry settler tanks accumulate catalyst fines suspended in slurry oil, forming concrete-like solids impregnated with hydrocarbons that constitute hazardous waste [18].

Attrition

Attrition involves the physical breakdown of catalyst particles due to mechanical stresses encountered during reactor loading, operation, and regeneration cycles. This phenomenon is particularly prevalent in fluidized bed and moving bed reactor systems where particle-to-particle and particle-to-reactor wall contacts generate continuous abrasive forces.

While the search results provide limited specific details on attrition mechanisms, this form of mechanical degradation produces fine catalyst particles that can be elutriated from the reactor system, resulting in catalyst inventory loss and potential downstream equipment fouling. Attrition typically manifests through three primary pathways: (1) surface abrasion that gradually reduces particle size, (2) particle fragmentation that generates new fines, and (3) impact failure that causes catastrophic particle fracture.

Quantitative Deactivation Modeling

Mathematical modeling of catalyst deactivation plays a crucial role in process simulation, reactor design, and optimization of industrial catalytic reactors [6]. Deactivation models can be categorized as selective or non-selective based on the mechanism of active site consumption, and as theoretical, empirical, or semi-empirical based on their mathematical derivation.

Table 1: Catalyst Deactivation Models for Mechanical Mechanisms

| Model Type | Mathematical Expression | Application Context | Key Parameters | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Dependent (Power Law) | a(t) = Atⁿ |

Fluidized catalytic cracking (FCC) | A = pre-exponential factor, n = decay order, t = time | [6] |

| Time-Dependent (Exponential) | a(t) = e^(-αt) |

Catalytic pyrolysis of gas oils; Propane dehydrogenation | α = deactivation coefficient, t = time-on-stream | [6] |

| Temperature-Dependent | a = α₀e^(-αt) α = A·exp(-E/RT) |

FCC; Biomass-derived chemicals | α₀ = initial activity, E = activation energy, R = gas constant, T = temperature | [6] |

| Generalized Power Law | -da/dt = k_d·aⁿ a = e^(-k_d t) (n=1) a = 1/(1 + k_d t) (n=2) |

Fischer-Tropsch synthesis; Ethylbenzene dehydrogenation | k_d = deactivation rate constant, n = deactivation order | [6] |

| Coke Content-Based | a(t) = f(C_coke) |

Vacuum gas oil (VGO) cracking | C_coke = coke content on catalyst | [6] |

The choice of an appropriate deactivation model depends on the specific catalyst system, reaction conditions, and dominant deactivation mechanism. For rapid deactivation processes such as FCC, time-dependent models often provide sufficient accuracy, while more complex systems requiring precise activity prediction may necessitate models incorporating temperature, coke content, and reactant concentration dependencies [6].

Experimental Methodologies for Deactivation Analysis

Laboratory-Scale Deactivation Protocols

Figure 2 outlines a generalized experimental workflow for investigating mechanical deactivation mechanisms.

Figure 2. Experimental Workflow for Deactivation Studies. This diagram outlines the systematic approach for investigating mechanical deactivation mechanisms in laboratory settings.

Catalyst Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive catalyst characterization before and after deactivation provides critical insights into mechanical degradation mechanisms:

- Textural Properties: Nitrogen physisorption measurements determine surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution changes following fouling or coking [17].

- Coke Characterization: Temperature-programmed oxidation (TPO), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and Raman spectroscopy identify coke quantity, structure, and location [16].

- Mechanical Strength: Attrition resistance testing through ASTM standard methods evaluates particle integrity under simulated operating conditions.

- Morphological Analysis: Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) visualizes surface deposits, pore blockage, and particle fragmentation [17].

Accelerated Deactivation Protocols

Controlled laboratory deactivation studies employ strategic approaches to simulate long-term operational impacts:

- Extended Time-on-Stream: Operating catalysts beyond normal lifespan under standard conditions to observe natural deactivation progression [6].

- Severity Enhancement: Increasing temperature, introducing model foulants, or extending cycle times to accelerate deactivation mechanisms.

- Model Compound Introduction: Adding known coking precursors (e.g., polyaromatics) or foulants (e.g., metalorganic compounds) to feedstock.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Deactivation and Regeneration Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Deactivation/Regeneration Research | Application Context | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidizing Agents | O₂, O₃, NOₓ | Coke combustion; Catalyst regeneration | Oxidation-based regeneration protocols | [3] [16] |

| Gasification Agents | CO₂, H₂O | Coke gasification to syngas; Alternative regeneration | Sustainable regeneration with value recovery | [16] |

| Reducing Agents | H₂, NaBH₄ | Coke hydrocracking; Catalyst reduction | Hydrogenation-based regeneration; Pd catalyst activation | [16] [19] |

| Model Coke Precursors | Polyaromatic compounds; Phenol | Controlled coking studies; Deactivation mechanism elucidation | Laboratory deactivation protocols | [17] |

| Supercritical Fluids | CO₂ (scCO₂) | Coke extraction; Pore cleaning | Supercritical fluid extraction regeneration | [3] [16] |

| Acid-Base Reagents | NH₄OAc; Phosphate buffers | pH control; Reaction medium optimization | Pd-catalyzed deallylation assays | [19] |

Regeneration Strategies for Mechanical Deactivation

Conventional Regeneration Approaches

Oxidation-Based Regeneration

Oxidation represents the most widely applied regeneration method for coke deactivation, typically employing air or oxygen at elevated temperatures:

- Air/O₂ Combustion: Industrial standard for FCC and other petrochemical processes; exothermic nature requires careful temperature control to prevent catalyst damage [16].

- Ozone (O₃) Treatment: Enables low-temperature regeneration; effectively regenerates coked ZSM-5 catalysts while minimizing thermal degradation [3] [16].

- Oxynitride (NOₓ) Applications: Alternative oxidants that can modify combustion pathways and reduce local hot spots.

The exothermic nature of coke combustion presents significant challenges, including localized temperature gradients (hot spots) that can permanently damage catalyst structure through sintering or phase transformation [3] [16]. Sophisticated reactor control strategies are essential for managing these thermal effects during commercial regeneration operations.

Gasification and Hydrogenation

Alternative regenerative approaches focus on chemical conversion rather than combustion of carbonaceous deposits:

- CO₂ Gasification: Converts coke to CO via Boudouard reaction (C + CO₂ → 2CO); produces valuable syngas while reducing CO₂ emissions [16].

- Steam Reforming: Reacts coke with H₂O to generate CO/H₂ mixtures; simultaneously cleans catalyst and produces useful synthesis gas.

- Hydrogen Treatment: Employes H₂ for hydrocracking of carbon deposits; particularly effective for aliphatic coke components [16].

Emerging Regeneration Technologies

Advanced regeneration methodologies continue to evolve, offering improved efficiency and reduced environmental impact:

- Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE): Utilizes unique solvent and transport properties of supercritical fluids (e.g., CO₂) to extract coke from porous catalyst matrices at moderate temperatures [3] [16].

- Microwave-Assisted Regeneration (MAR): Applies selective heating mechanisms that can potentially reduce energy consumption and improve coke removal efficiency.

- Plasma-Assisted Regeneration (PAR): Employs non-thermal plasma to activate regeneration reactions at lower temperatures.

- Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD): Techniques that can potentially restore or protect catalyst surfaces during regeneration cycles [3].

Environmental Implications and Sustainability Considerations

Regeneration of catalysts deactivated by mechanical mechanisms carries significant environmental implications that must be addressed within modern sustainability frameworks:

- CO₂ Emissions: Conventional combustion-based regeneration in FCC units alone contributes 40-45% of total CO₂ emissions from refinery operations [16].

- Alternative Approaches: Gasification-based regeneration methods transform coke into synthesis gas (CO + H₂), simultaneously restoring catalyst activity and producing valuable chemical feedstocks [16].

- Waste Minimization: Advanced extraction technologies enable conversion of hazardous waste materials (e.g., K-coded catalyst fines) to non-hazardous status through constituent removal, significantly reducing disposal challenges [18].

Life cycle assessment (LCA) and techno-economic analysis (TEA) methodologies provide critical frameworks for evaluating the environmental footprint and economic viability of regeneration strategies, particularly when comparing conventional and emerging technologies [17].

Mechanical deactivation through fouling, coking, and attrition remains an inevitable challenge in industrial catalytic processes, particularly in petrochemical operations and emerging biomass conversion technologies. A comprehensive understanding of these mechanisms—supported by robust mathematical modeling and advanced characterization techniques—enables the development of effective mitigation and regeneration strategies. The ongoing evolution of regeneration technologies, particularly those emphasizing environmental sustainability and circular economy principles, continues to enhance catalyst longevity and process efficiency. Future research directions should focus on integrated approaches combining advanced materials design with sophisticated process control to minimize deactivation impacts while maximizing catalyst service life within the broader context of sustainable chemical processing.

Catalyst deactivation represents a fundamental challenge in industrial catalysis, directly impacting process efficiency, economic viability, and environmental sustainability. Among various deactivation pathways, thermal mechanisms including sintering and thermal degradation constitute irreversible processes that critically diminish catalyst performance by altering the active phase microstructure and chemical composition [20]. Within the broader context of catalyst deactivation and regeneration research, understanding these thermally-induced phenomena is paramount for developing next-generation catalytic systems with enhanced longevity and stability under demanding operational conditions. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical examination of sintering and thermal degradation mechanisms, integrating current scientific understanding with practical methodologies for their investigation and mitigation.

Sintering describes the thermal-induced agglomeration of catalyst nanoparticles, resulting in reduced active surface area, while thermal degradation encompasses broader material transformations including phase changes, solid-state reactions, and support collapse [3] [20]. These processes manifest across diverse catalytic systems—from supported metal catalysts in petroleum refining to ceramic oxide systems in high-temperature applications—imposing significant limitations on catalyst lifetime and regeneration potential [21] [22]. The following sections present a detailed analysis of these mechanisms, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to researchers and development professionals engaged in catalyst design and optimization.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Sintering

Sintering represents a primary deactivation pathway for supported metal catalysts, involving the thermally-induced loss of active surface area through crystallite growth and migration. This process occurs via two predominant mechanisms: atomic migration (Ostwald ripening) involving the transport of individual metal atoms, and particle migration with subsequent coalescence [20]. The driving force for both pathways is the reduction of surface free energy, with kinetics strongly dependent on temperature, atmosphere, and metal-support interactions.

The microstructural evolution during sintering directly impacts catalytic performance metrics. Research on circular Al honeycombs demonstrates that elevated sintering temperatures (400–600°C) enhance metallurgical bonding but simultaneously promote elemental diffusion phenomena that alter local mechanical properties [21]. In supported catalyst systems, sintering progresses through distinct stages: initial rapid surface atom migration, followed by particle coalescence and eventual stabilization of larger, thermodynamically favored crystallites with diminished surface-to-volume ratios.

Table 1: Sintering Mechanisms and Characteristics

| Mechanism | Process Description | Temperature Dependence | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Migration (Ostwald Ripening) | Migration of individual atoms from smaller to larger particles | High, typically >0.3-0.5 Tmelt | Metal volatility, surface diffusivity, interfacial energy |

| Particle Migration & Coalescence | Movement and collision of entire crystallites | Moderate, >0.2 Tmelt | Metal-support interaction strength, particle size/mobility |

| Phase Transformation | Solid-state reactions and new phase formation | Variable, dependent on specific system | Chemical composition, atmosphere, support reactivity |

Thermal Degradation Pathways

Thermal degradation encompasses a spectrum of material transformations beyond simple particle growth, including phase segregation, support collapse, and chemical composition changes that collectively degrade catalytic function. In ceramic catalyst systems such as Al2O3/ZrO2 composites, thermal degradation manifests as accelerated grain growth, pore coarsening, and phase transformations that compromise mechanical integrity and active site accessibility [22].

The degradation of polyamide 12 (PA12) powder in selective laser sintering processes illustrates the complex interplay of thermal and oxidative pathways, where successive thermal cycles induce chain scission, cross-linking, and evaporation of low molecular weight components [23]. These chemical changes alter powder flowability, crystallinity, and ultimately the mechanical performance of fabricated parts—phenomena with direct parallels to catalyst thermal degradation.

Beyond structural changes, thermal degradation induces performance-impairing transformations including:

- Loss of structural promoters that stabilize active phases

- Collapse of porous networks essential for reactant access

- Solid-state reactions between active components and supports

- Vapor formation and transport of active species

Table 2: Thermal Degradation Manifestations in Different Catalyst Systems

| Catalyst System | Primary Thermal Degradation Modes | Critical Temperature Range | Performance Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supported Metals (Pt, Pd, Ni) | Metal support compound formation, pore collapse | 400-800°C | Active surface area loss, diffusion limitations |

| Metal Oxide Ceramics (Al2O3/ZrO2) | Polymorphic transformations, exaggerated grain growth | >1000°C | Mechanical failure, surface area reduction |

| Zeolites | Dealumination, framework collapse | >600°C | Acid site loss, structural degradation |

| Polymer-Based Systems (PA12) | Chain scission, cross-linking, oxidation | 140-200°C | Mechanical property deterioration, flowability reduction |

Experimental Methodologies for Investigation

Thermal Analysis Protocols

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) provides quantitative data on thermal stability and decomposition profiles. For Al2O3/ZrO2 composites, samples are heated from ambient to 1400°C at 2°C/min in air atmosphere, with mass changes recorded to determine decomposition temperatures and stability thresholds [22]. This methodology identifies organic additive removal temperatures and initial sintering onset.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) reveals thermal transitions and energetics of degradation processes. In PA12 powder studies, DSC analysis employs heating rates of 10°C/min under nitrogen purge from 25°C to 220°C, with subsequent cooling and reheating cycles to quantify crystallinity changes and oxidative degradation [23]. The degree of crystallinity is calculated from melting enthalpies relative to 100% crystalline reference materials.

Structural and Microstructural Characterization

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) identifies phase evolution during thermal treatment. Protocol specifications include: Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), 40 kV operating voltage, 30 mA current, and 0.02° step size over 10-80° 2θ range [22]. Rietveld refinement quantifies phase fractions and crystallite size using Scherrer equation analysis, detecting transitions such as γ-Al2O3 to α-Al2O3 or tetragonal to monoclinic ZrO2.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) visualizes microstructural evolution. Samples are prepared by dispersion on conductive carbon tape with gold sputter coating (10-15 nm thickness) to prevent charging [23]. Imaging at 10-15 kV accelerating voltage with secondary electron detection reveals particle morphology, grain growth, and pore structure changes at various sintering stages.

Physical Property Measurements

Dilatometric Analysis determines dimensional changes during sintering. For technical ceramics, measurements employ heating rates of 2-5°C/min to 1400-1600°C in air atmosphere, with sample dimensions precisely recorded to calculate linear shrinkage, sintering rates, and coefficient of thermal expansion [22].

Porosity and Density Analysis combines helium pycnometry (DIN 66137-2) for true density with Archimedes method (ISO 60) for bulk density, enabling calculation of total porosity and pore size distribution changes after thermal treatment [23].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for sintering and thermal degradation analysis

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Sintering and Thermal Degradation Research

| Material/Reagent | Specification | Research Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al2O3 Powder | TM-DAR, particle size 0.12 ± 0.3 µm [22] | Ceramic matrix material | High-temperature catalyst support studies |

| ZrO2 Powder | TZ-PX-245, 3% mol Y2O3 stabilized, 0.04 µm [22] | Phase-stabilized ceramic component | Composite catalyst supports investigation |

| Diammonium Hydrogen Citrate (DAC) | Analytical grade, Sigma-Aldrich [22] | Dispersing agent for ceramic slurries | Slip casting preparation of model structures |

| Citric Acid (CA) | Analytical grade, POCH Gliwice/Avantor [22] | Co-dispersant for colloidal processing | pH adjustment and suspension stabilization |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | 10% aqueous solution, Sigma-Aldrich [22] | Binder for green body formation | Providing mechanical strength before sintering |

| PA12 Powder | PA 2200, virgin material [23] | Polymer catalyst model system | Thermal degradation and recycling studies |

| Nitrogen Gas | High purity (99.999%) | Inert atmosphere provision | Oxidative degradation prevention during testing |

Data Presentation and Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative assessment of sintering and thermal degradation provides critical insights for catalyst design and operational parameter optimization. The following tables consolidate experimental data from multiple research studies to establish performance thresholds and degradation kinetics.

Table 4: Sintering Temperature Effects on Material Properties in Al/Mg Systems

| Sintering Temperature (°C) | Phase Composition | Diffusion Depth (µm) | Microhardness (HV) | Plateau Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 400 | Al3Mg2 and Al12Mg17 [21] | Minimal | Baseline | Not reported |

| 450 | Al(Mg) solid solution only [21] | Moderate | Enhanced | Not reported |

| 500 | Al(Mg) solid solution [21] | Significant | Further enhanced | Not reported |

| 600 | Al(Mg) solid solution [21] | Maximum | Maximum | 63.2 |

Table 5: Thermal Degradation Indicators in PA12 Powder During Reuse Cycles

| Reuse Cycle | Crystallinity (%) | Molecular Weight Change | Particle Fracturing | Flowability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virgin | Maximum [23] | Baseline | Minimal | Optimal |

| 2nd | Slight decrease [23] | Moderate increase | Minor | Slight reduction |

| 4th | Noticeable decrease [23] | Significant increase | Apparent | Moderate reduction |

| 6th | Substantial decrease [23] | Maximum observed | Pronounced | Significantly impaired |

| 8th | Minimum [23] | Stabilized at high values | Severe | Poor |

Diagram 2: Interrelationships in thermal degradation pathways

Mitigation Strategies and Regeneration Approaches

Addressing sintering and thermal degradation requires multifaceted strategies encompassing material design, operational parameters, and regeneration protocols. Effective mitigation approaches include:

Stabilization through Structural Promoters: Incorporating thermally stable additives such as Y2O3-stabilized ZrO2 inhibits phase transformations and retards grain growth up to 1400°C [22]. These structural promoters create diffusion barriers that impede atomic migration, thereby preserving surface area and active site distribution under thermal stress.

Advanced Regeneration Techniques: Emerging methods including microwave-assisted regeneration (MAR) and plasma-assisted regeneration (PAR) enable controlled thermal treatment that removes deactivating deposits while minimizing structural damage to the catalyst foundation [3]. These techniques offer superior temperature control compared to conventional thermal regeneration, preventing additional sintering during reactivation cycles.

Operational Parameter Optimization: Strategic control of process conditions—including temperature ramping rates (2-5°C/min optimal for ceramics), atmosphere composition (nitrogen vs. air), and maximum temperature exposure—significantly influences degradation kinetics [22] [23]. Implementation of thermal cycling protocols with controlled cooling phases further mitigates cumulative damage.

The integration of these approaches within a comprehensive catalyst lifecycle management strategy extends functional longevity while maintaining catalytic performance across operational campaigns. Future research directions focus on nanoscale stabilization mechanisms and computational modeling of thermal degradation kinetics to enable predictive catalyst design for specific temperature regimes.

Impacts of Deactivation on Process Efficiency and Economics

Catalyst deactivation, the irreversible loss of catalytic activity and/or selectivity over time, represents a fundamental challenge with profound economic consequences across the chemical process industries. While catalysts are not consumed in stoichiometric quantities, they are not immune to degradation, making deactivation an inevitable phenomenon that directly impacts process efficiency, operational costs, and environmental sustainability. The maintenance of catalyst activity for as long as possible is of major economic importance in industry, with costs for catalyst replacement and process shutdown totaling billions of dollars per year [2]. The time scales for deactivation vary considerably—from seconds for fluid catalytic cracking catalysts to over a decade for ammonia synthesis catalysts—yet the consequences consistently affect the bottom line [3] [2]. This technical review examines the multifaceted impacts of catalyst deactivation on process efficiency and economics, providing a structured framework for understanding, quantifying, and mitigating these effects within the broader context of catalyst deactivation and regeneration research.

Fundamental Deactivation Mechanisms and Their Economic Ramifications

Catalyst deactivation manifests through three primary mechanisms: chemical, thermal, and mechanical. Each pathway uniquely influences catalyst longevity and process economics, with specific mitigation strategies required for different deactivation modes.

Chemical Deactivation: Poisoning and Fouling

Chemical deactivation occurs when catalyst active sites are compromised through strong chemical interactions with feedstream components. Catalyst poisoning involves the strong chemisorption of impurities such as sulfur, silicon, arsenic, and phosphorus on active sites, rendering them unavailable for the intended reaction [8] [2]. The economic impact of poisoning is particularly severe in processes utilizing precious metal catalysts, where even parts-per-million levels of contaminants can significantly reduce activity. For instance, sulfur acts as a severe poison for steam reforming catalysts containing group VIII metals like nickel, necessitating expensive feedstock purification systems [2]. Poisoning can be reversible or irreversible depending on adsorption strength and operating conditions, with irreversible poisoning necessitating complete catalyst replacement.

Fouling or coking represents the most common chemical deactivation mechanism, involving physical deposition of carbonaceous species (coke) on the catalyst surface and pores [14] [3]. Coke formation occurs through three distinct stages: hydrogen transfer at acidic sites, dehydrogenation of adsorbed hydrocarbons, and gas-phase polycondensation [3]. These carbon deposits affect catalyst performance through two primary pathways: active site poisoning through overcoating and pore clogging that prevents reactant access to active sites [3]. The economic impact of coking is particularly significant in petrochemical processes, where rapid coke formation may require continuous regeneration systems such as those employed in fluidized catalytic cracking (FCC) units [3].

Thermal and Mechanical Deactivation

Thermal degradation (sintering) occurs when high temperatures cause catalyst particles to agglomerate, reducing the active surface area and catalytic activity [8]. This process is accelerated by the presence of water vapor and is generally irreversible, representing a permanent loss of catalyst functionality [8] [2]. Sintering is thermodynamically favored since high-surface-area materials are inherently unstable, with catalysts tending toward more favorable lower surface area agglomerates under demanding process conditions [2].

Mechanical deactivation includes fouling/masking, attrition, and crushing. Fouling involves deposition of external materials onto the catalyst surface, while attrition and crushing result from mechanical stresses in fluidized or slurry beds that break down catalyst particles [8] [2]. These mechanical failures lead to increased pressure drops across reactors, channeling that bypasses reactants, and ultimately complete reactor shutdown when operational limits are exceeded. The economic impact includes not only catalyst replacement costs but also significant downtime during reactor unloading and reloading.

Table 1: Primary Catalyst Deactivation Mechanisms and Economic Consequences

| Deactivation Mechanism | Primary Causes | Economic Impact | Typical Industries Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poisoning | Impurities in feed (S, P, Si, As, metals) | Reduced reaction rates, increased feedstock purification costs, catalyst replacement | Refining, ammonia synthesis, reforming |

| Coking/Fouling | Carbon deposition from side reactions | Frequent regeneration requirements, reduced selectivity, reactor shutdown | FCC, petrochemicals, biomass conversion |

| Sintering | High temperatures, steam | Permanent activity loss, catalyst replacement | High-temperature processes, reforming |

| Attrition/Crushing | Mechanical stress, thermal cycling | Pressure drop increase, reactor channeling, shutdown | Fluidized beds, slurry reactors |

Quantitative Assessment of Deactivation Impacts

Measuring Deactivation and Its Economic Effects

Catalyst activity (a) is quantitatively defined as the ratio of the reaction rate at a given time (t) to the reaction rate at the start of catalyst use (t=0): Activity (t) = r(t) / r(t=0) [2]. This declining activity directly correlates with reduced process efficiency and economic performance. The economic impacts manifest through multiple pathways:

1. Reduced Production Capacity: Decreasing catalyst activity leads to lower conversion rates, reducing throughput and product yield. For continuous processes operating at fixed conditions, this results in diminished production capacity over time. In batch processes, it may require longer reaction times to achieve target conversions, reducing effective capacity.

2. Increased Operational Costs: Deactivated catalysts often require more severe operating conditions (higher temperatures and pressures) to maintain target conversion levels, significantly increasing energy consumption and utility costs [2]. Additionally, declining selectivity increases raw material consumption per unit of product and raises purification costs for downstream processing.

3. Catalyst Replacement and Regeneration Expenses: The direct costs of catalyst replacement include not only the new catalyst materials but also reactor downtime, labor for changeout, and disposal of spent materials. For precious metal catalysts, these costs can be substantial. Regeneration processes, while less expensive than replacement, still involve operational costs for regeneration media (hydrogen, oxygen, steam) and associated energy inputs [3].

4. Environmental and Compliance Costs: Deactivated catalysts often exhibit reduced selectivity, leading to increased byproduct formation and waste streams. In emission control applications, deactivation can result in non-compliance with environmental regulations, potentially leading to fines and operational restrictions [8].

Table 2: Quantitative Economic Impact of Catalyst Deactivation

| Economic Factor | Impact Range | Key Influencing Variables | Mitigation Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Lifetime | Seconds (FCC) to 10+ years (NH₃) | Process conditions, feedstock purity, catalyst design | Guard beds, feedstock purification, optimized formulations |

| Activity Decline Rate | 2-15% per year in well-controlled processes | Temperature, poison concentration, thermal stability | Temperature control, poison removal, metal-support interactions |

| Regeneration Frequency | Continuous (FCC) to never (some bulk chemicals) | Coke formation rate, catalyst robustness | Hydrogen co-feeding, optimized reactor design |

| Replacement Costs | 2-15% of total production costs | Catalyst type (precious metals vs. oxides), reactor size | Extended lifetime, regeneration protocols, recovery of valuable components |

Case Study: Economic Impact in Ammonia Production

In ammonia plants, catalyst deactivation occurs through multiple mechanisms including poisoning by sulfur compounds, coking, and thermal degradation [2]. The historical improvement in catalyst formulations has extended average catalyst lifetime from 2-3 years to 5-6 years, representing substantial economic benefits through reduced replacement frequency and less downtime [2]. Key performance parameters including lower pressure drop, reduced tube wall temperatures, and extended operation near equilibrium conversion directly translate to improved process efficiency and economics. The development of catalysts with better coke resistance, easy reducibility, higher mechanical strength, and improved thermal stability has been instrumental in achieving these economic gains [2].

Methodologies for Assessing Deactivation and Economic Impact

Experimental Protocols for Deactivation Analysis

Researchers employ standardized experimental methodologies to quantify deactivation rates and mechanisms, providing critical data for economic assessments. The following protocol exemplifies approaches used in academic and industrial research settings:

Accelerated Deactivation Testing Protocol

Fresh Catalyst Characterization:

- Determine baseline surface area via BET method [8]

- Analyze pore volume and distribution using mercury porosimetry or nitrogen adsorption

- Identify active component dispersion through chemisorption techniques

- Establish crystallite size and structure via X-ray diffraction (XRD)

Controlled Deactivation:

- Expose catalyst to model feed containing known poisons (e.g., H₂S for sulfur poisoning) or coke precursors (e.g., olefins at elevated temperatures)

- Utilize extended-duration experiments to evaluate catalysts after initial "break-in" period [5]

- Employ in situ and operando characterization methods to probe changes in active sites and surface species during reactions [5]

Post-Test Characterization:

- Measure changes in surface area, pore volume, and active site concentration

- Identify poison deposition through elemental analysis techniques (XRF, PIXE) [8]

- Detect chemical state changes via X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) [8]

- Analyze carbon deposits through temperature-programmed oxidation (TPO)

Kinetic Measurement:

- Determine reaction rates at standardized conditions before and after deactivation

- Quantify selectivity changes to byproducts

- Measure activation energy changes to identify deactivation mechanisms

This systematic approach enables researchers to correlate operational parameters with deactivation rates, providing essential data for economic modeling and lifetime predictions.