Electronic Structure Descriptors for Catalyst Design: From Fundamental Theory to AI-Driven Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electronic structure descriptors, powerful tools that correlate a material's fundamental electronic properties with its catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability.

Electronic Structure Descriptors for Catalyst Design: From Fundamental Theory to AI-Driven Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electronic structure descriptors, powerful tools that correlate a material's fundamental electronic properties with its catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability. We explore the foundational theory behind key descriptors like the d-band center and oxygen p-band center, and detail their practical application in designing diverse catalysts, from single-atom sites to complex oxides. The content further addresses central challenges, including scaling relationships and computational transferability, while highlighting how the integration of machine learning and high-throughput screening is revolutionizing descriptor development. By synthesizing insights from recent literature, this review serves as a guide for researchers aiming to understand, apply, and advance these descriptors for the rational design of next-generation catalysts in energy conversion and beyond.

What Are Electronic Structure Descriptors? Core Concepts and Physical Origins

In the field of catalyst design, electronic structure descriptors are quantitative parameters that bridge the atomic-scale electronic structure of a material and its macroscopic catalytic properties. The foundational principle is that a material's electronic structure determines its interaction with reactant molecules, thereby governing catalytic activity and selectivity [1]. The advent of density functional theory (DFT) has provided a robust theoretical framework for calculating these descriptors with accuracy comparable to post-Hartree-Fock methods but at a computational cost suitable for high-throughput screening [1] [2]. This guide details the core descriptors, their calculation methodologies, and practical applications, providing researchers with the tools to accelerate the discovery and optimization of catalytic materials.

Fundamental Electronic Structure Descriptors

Theoretical Foundations and Key Descriptor Definitions

Electronic structure descriptors are derived from the analysis of a catalyst's electron density distribution and its response to perturbations. Under the framework of conceptual DFT (CDFT), also known as density functional reactivity theory, several global reactivity descriptors have been rigorously defined [1]. These descriptors provide insights into a molecule's or solid's intrinsic tendency to donate or accept electrons.

Table 1: Fundamental Global Reactivity Descriptors from Conceptual DFT

| Descriptor | Mathematical Definition | Physical Interpretation | Role in Catalysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Potential (μ) | μ ≈ (EHOMO + ELUMO)/2 | The negative of electronegativity; tendency of electrons to escape from a system. | Indicates the general driving force for electron transfer between catalyst and adsorbate. |

| Hardness (η) | η ≈ (ELUMO - EHOMO)/2 | Resistance to charge transfer; large band gap in solids. | Correlates with catalytic stability; harder systems are less reactive but more stable. |

| Softness (S) | S = 1/(2η) | Reciprocal of hardness; propensity to undergo charge transfer. | Softer systems are generally more reactive in catalytic cycles involving electron exchange. |

| Electrophilicity Index (ω) | ω = μ²/(2η) | A measure of the energy lowering due to maximal electron flow between a system and its environment. | Quantifies the overall power of a catalyst to act as an electron acceptor. |

Beyond these global descriptors, local descriptors offer site-specific predictions crucial for heterogeneous catalysis where reactivity is localized to surface atoms. The Fukui function is a key local descriptor, defined as the derivative of the electron density with respect to the number of electrons at a constant external potential, f(r) = (∂ρ(r)/∂N)v(r) [1]. It identifies the most susceptible sites for nucleophilic (f⁺(r)) or electrophilic (f⁻(r)) attack. For metallic surfaces, the d-band center (εd), which represents the average energy of the d-band projected onto surface atoms, has been a cornerstone descriptor. It successfully correlates with adsorption energies of small molecules, where an upshifted (closer to the Fermi level) d-band center typically strengthens adsorbate binding [2].

Advanced and Composite Descriptors

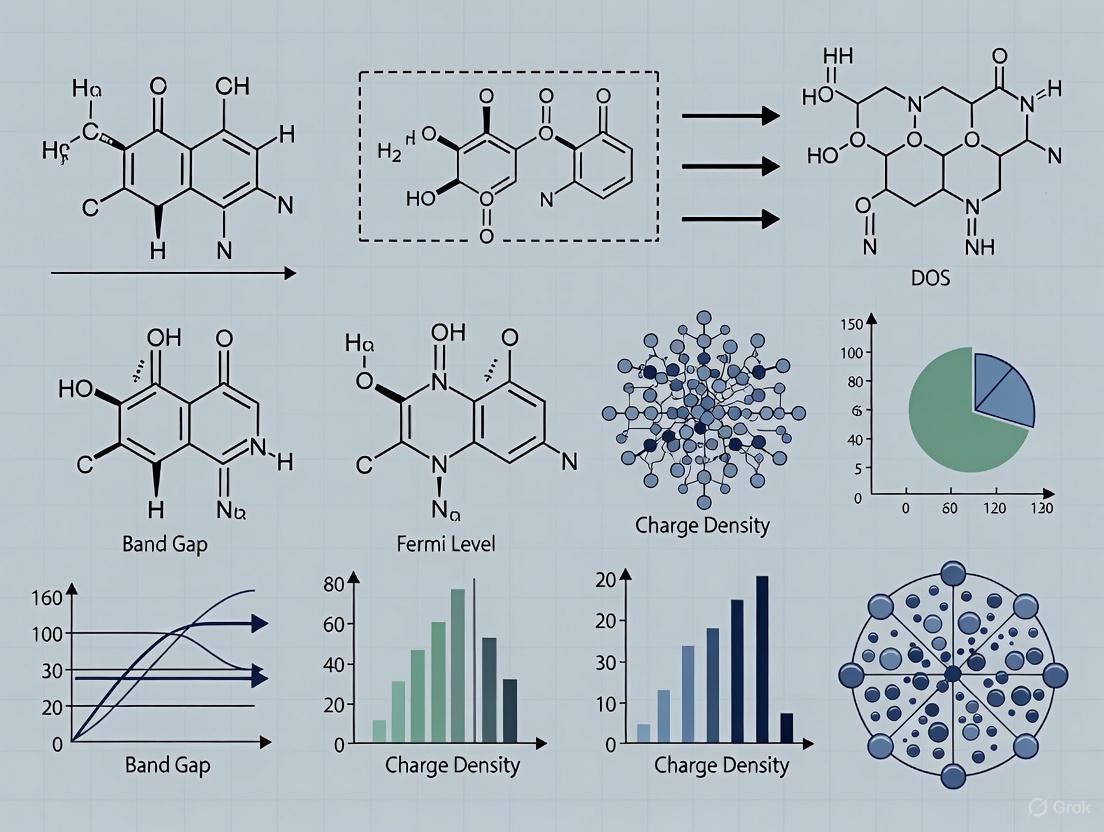

While the d-band center is powerful, it does not capture the full complexity of surface reactivity. The shape and breadth of the d-band, characterized by its higher moments, provide a more complete picture [2]. Furthermore, for reactions where interactions with sp-electrons are significant, the full density of states (DOS) pattern is a more comprehensive descriptor [2]. A quantitative metric for comparing DOS patterns, ΔDOS, can be defined as the integrated squared difference between the DOS of an alloy and a reference catalyst (e.g., Pd), weighted by a Gaussian function centered at the Fermi level [2]:

ΔDOS_2-1 = { ∫ [ DOS₂(E) - DOS₁(E) ]² g(E;σ) dE }^(1/2), where g(E;σ) is a Gaussian function with a standard deviation σ (e.g., 7 eV) to emphasize states near the Fermi energy [2].

Recent studies also highlight the utility of derived descriptors like the d-band center gap (Δd), which tracks changes in the electronic structure induced by a modifier. For instance, in Zr-modified Ni catalysts for hydrogenation, the Δd decreases linearly with increasing Zr concentration and shows a strong linear correlation with the adsorption energy of key intermediates and the energy barrier of the rate-determining step [3].

Computational-Experimental Workflow for Descriptor Validation

The power of descriptors is fully realized when integrated into a combined computational-experimental workflow for catalyst discovery and validation.

Diagram 1: High-throughput computational-experimental screening protocol for discovering bimetallic catalysts, adapted from [2].

High-Throughput Computational Screening Protocol

The process begins with defining a reference catalyst and target reaction. As demonstrated in a study aiming to replace Pd for H₂O₂ synthesis, the first step is a high-throughput DFT screening of a large space of potential materials (e.g., 4,350 bimetallic alloy structures) [2].

- Thermodynamic Stability Screening: For each candidate structure, the formation energy (ΔEf) is calculated. A threshold (e.g., ΔEf < 0.1 eV) is applied to filter for thermodynamically stable or metastable alloys that are likely synthesizable and resistant to phase separation under reaction conditions [2].

- Descriptor Calculation: For the thermodynamically stable candidates (e.g., 249 alloys), electronic structure descriptors are computed. This involves a single-point DFT calculation on the optimized structure of the most stable close-packed surface (e.g., (111) for fcc alloys) to obtain the projected density of states (DOS) onto surface atoms [2].

- Similarity Quantification: The full DOS pattern of each candidate is quantitatively compared to that of the reference catalyst (Pd(111)) using the

ΔDOSdescriptor. Candidates with the lowestΔDOSvalues are prioritized for experimental synthesis, as electronic structure similarity suggests comparable catalytic properties [2].

Experimental Synthesis and Validation

The top-ranked candidates from computational screening (e.g., 8 alloys) are synthesized. Their catalytic performance is rigorously tested against the reference material for the target reaction (e.g., H₂O₂ direct synthesis from H₂ and O₂) [2]. This validation step is critical, as it confirms the predictive power of the descriptor. In the referenced study, four of the eight screened alloys exhibited performance comparable to Pd, with the newly identified Pd-free catalyst Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ showing a 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity [2].

Case Study: Descriptor-Guided Design of Ni-Based Catalysts

A detailed case study on designing Ni-based catalysts for the hydrogenation of 1,4-butynediol (BYD) illustrates the linear relationships that can exist between descriptors and catalytic parameters [3].

- Descriptor Definition: The study used the d-band center gap (Δd), defined as the change in the d-band center of the Ni(111) surface upon incorporation of Zr as an electronic inducer.

- Computational Methodology: A series of Zr-modified Ni(111) surface models with varying Zr concentrations were built. DFT calculations were performed to:

- Geometry-optimize the structures.

- Calculate the d-band center for each model to determine Δd.

- Compute the adsorption energy of the key reaction intermediate, cis-1,4-butenediol (cis-BED).

- Calculate the energy barrier for the hydrogenation step: cis-BED + H → cis-BEDH.

- Linear Relationships and Optimization: A strong linear correlation was observed between Δd and the cis-BED adsorption energy. Furthermore, the activation barrier for the key hydrogenation step showed a perfect linear relationship with Δd. The Δd reached a minimum at -0.67 eV for a Zr concentration of 36 at%, which corresponded to the most favorable adsorption energy and the lowest activation barrier (0.45 eV) [3].

Table 2: Correlation between Descriptor and Catalytic Properties in Ni-Zr System [3]

| Zr Concentration (at%) | d-band center gap, Δd (eV) | cis-BED Adsorption Energy (eV) | Activation Barrier (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 36 | -0.67 (Minimum) | -3.49 (Most Favorable) | 0.45 (Lowest) |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Correlation Trend | ↓ Linear decrease with Zr ↑ | ↓ Linear strengthening with decreasing Δd | ↓ Linear decrease with decreasing Δd |

This case demonstrates that the Δd descriptor serves as a powerful predictive tool for tuning catalyst composition to achieve optimal activity.

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Calculating Electronic Structure Descriptors

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Descriptor Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO | DFT Code | First-principles electronic structure calculations. | Workhorse for calculating DOS, d-band centers, and adsorption energies on surfaces. [2] |

| Multiwfn | Wavefunction Analysis | A multifunctional program for analyzing wavefunctions. | Calculates various quantum chemical descriptors (global, local) and supports visualization. Compatible with major DFT codes. [1] |

| Dragon | Commercial Software | Computes >5,000 molecular descriptors. | Useful for QSAR modeling and calculating a wide range of topological and electronic descriptors. [4] |

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Provides cheminformatics and machine learning tools. | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints for QSAR modeling and virtual screening. [4] |

Experimental Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental validation of descriptor-predicted catalysts requires specific materials and characterization techniques.

Table 4: Essential Materials and Methods for Experimental Validation

| Item / Method | Function in Catalyst Development | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Salts | Source of metal components for catalyst synthesis. | Chloride or nitrate salts of candidate metals (e.g., Ni, Pt, Zr) for impregnation or co-precipitation synthesis. [3] |

| High-Surface-Area Supports | Provide a dispersed, stable platform for active metal nanoparticles. | Commonly used supports include γ-Al₂O₃, SiO₂, or carbon materials. [3] |

| Tube Furnace / Reactor | For catalyst calcination and reduction under controlled atmosphere. | Essential for activating the catalyst (e.g., reducing metal oxides to metallic form in H₂ flow). [2] [3] |

| Autoclave Reactor | Conduct catalytic reactions under controlled pressure and temperature. | Used for testing hydrogenation reactions (e.g., BYD hydrogenation) under H₂ pressure. [3] |

| XPS (X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy) | Determine surface elemental composition and oxidation states. | Confirms the successful incorporation of electronic inducers (e.g., Zr) and their interaction with the host metal (e.g., Ni). [3] |

Electronic structure descriptors provide an indispensable bridge between quantum-level calculations and macroscopic catalytic performance. The progression from single-parameter descriptors like the d-band center to more comprehensive ones like the full DOS pattern or the d-band center gap (Δd) has significantly enhanced our ability to predict and design catalysts. The outlined workflows, from high-throughput screening to detailed linear scaling relationship studies, demonstrate a powerful paradigm for modern catalyst discovery. By leveraging these descriptors and the associated computational-experimental toolkit, researchers can systematically navigate the vast chemical space to design highly efficient, selective, and cost-effective catalysts for a wide range of applications.

In the pursuit of rational catalyst design, researchers have long sought fundamental electronic structure descriptors that reliably predict catalytic activity and selectivity. A descriptor is a quantitative or qualitative measure that captures key properties of a system, enabling the understanding of relationships between a material's structure and its function [5]. The evolution of these descriptors began in the 1970s with energy-based parameters such as adsorption heats, which were used to construct volcano plots that visualized activity trends [5]. However, these early descriptors provided limited information about electronic structures and faced challenges in explaining specific electronic behaviors at the molecular level.

A transformative advancement occurred in the 1990s when Jens Nørskov and Bjørk Hammer introduced the d-band center theory for transition metal catalysts [5]. This theory established a correlation between the position of the d-band center relative to the Fermi level and the adsorption strength of adsorbates on metal surfaces [5]. For the first time, researchers could utilize molecular d-orbital information from a microscopic perspective to gain crucial insights into catalyst activity and selectivity. The d-band center theory has since evolved into a pivotal theoretical framework in surface science and catalysis chemistry, elucidating the essence of catalytic activity on transition metal surfaces through its pioneering perspective on the complex interaction between d-electron configuration and chemical adsorption processes [6].

This whitepaper provides an in-depth examination of the d-band center theory, detailing its fundamental principles, mathematical formalisms, and applications in predicting transition metal catalytic properties. Within the broader context of electronic structure descriptors for catalyst design, we explore how this theory has enabled systematic predictive capabilities for evaluating and optimizing electrocatalytic performance, particularly in sustainable energy technologies such as water electrolysis [6].

Theoretical Foundations of the d-Band Center Model

Fundamental Principles and Historical Development

The d-band center theory represents a cornerstone in surface catalysis, providing a fundamental descriptor that links the electronic structure of transition metals to their catalytic properties. Originally proposed by Professor Jens K. Nørskov, this theory defines the d-band center as the weighted average energy of the d-orbital projected density of states (PDOS) for transition metal alloys, typically referenced relative to the Fermi level [7]. This quantity plays a crucial role in determining the adsorption strength of reactants or intermediates on transition metal surfaces, serving as an essential electronic descriptor for adsorption behavior in heterogeneous catalysis [7].

The theoretical foundation rests upon the unique characteristics of transition metal electrons. In transition metals, the total electronic band structure can be divided into sp, d, and other bands. The reconstructed orbitals formed by the 2p orbitals and sp bands have similar energy ranges and shapes, while the d-band plays a crucial role, as the energy of the d-band relative to the Fermi level predicts bond strength [5]. When the d-band center is higher (closer to the Fermi level), stronger adsorbate bonding occurs due to elevated anti-bonding state energies [5]. Conversely, catalysts with low d-state energies often fill anti-bonding states, weakening adsorption bonds [5].

Table: Fundamental Components of d-Band Center Theory

| Component | Description | Role in Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| d-Orbitals | Partially filled electron orbitals in transition metals | Primary interaction center for adsorbate molecules |

| Fermi Level | Highest occupied electron energy level at absolute zero | Reference point for d-band center position |

| Projected Density of States (PDOS) | Distribution of electron states per energy interval | Determines d-band center calculation |

| Anti-bonding States | Molecular orbitals with reduced electron density between nuclei | Occupation level determines adsorption strength |

| sp-Bands | Broad electronic bands from s and p orbital hybridization | Modify d-orbital interactions through hybridization |

Mathematical Formulation

The d-band center (εd) is mathematically defined as the first moment of the d-projected density of states relative to the Fermi level. The standard calculation involves performing an energy-weighted integration of the PDOS of the d orbitals within a selected energy window [7]. This is formally expressed as:

Where E is the energy relative to the Fermi level, and ρd(E) is the density of states for the d-orbitals [5]. This calculation is typically performed using Density Functional Theory (DFT) by analyzing the density of states for the d-orbitals [5].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationship between d-band center position and adsorption strength:

Diagram 1: Relationship between d-band center position and adsorption strength. A higher d-band center (closer to Fermi level) leads to stronger adsorption, while a lower d-band center results in weaker adsorption.

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Density Functional Theory Calculations

The accurate determination of d-band center values relies heavily on Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, which provide the foundational electronic structure information. The standard protocol involves several systematic steps to ensure computational accuracy and reliability:

Structure Optimization: Begin with geometry optimization of the catalyst model system until forces on atoms are below a predefined threshold (typically 0.01-0.02 eV/Å) [7].

Electronic Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculation: Perform SCF calculations with appropriate k-point sampling and plane-wave energy cutoff to achieve total energy convergence (e.g., 10⁻⁵ eV/atom) [7].

Projected Density of States (PDOS) Analysis: Calculate the d-orbital projected density of states using a finer k-point mesh for accurate DOS sampling [7].

d-Band Center Calculation: Compute εd through numerical integration of the d-PDOS using the standard moment formula [5] [7].

For systems with strong electron correlations, particularly those containing localized d or f electrons, the DFT+U method incorporates an effective Hubbard U parameter to better describe on-site Coulomb interactions [8]. This approach has proven essential for reproducing structural properties with high fidelity in correlated systems like transition metal oxides and complexes [8].

Table: Standard Computational Parameters for d-Band Center Calculations

| Parameter | Typical Values | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Cutoff | 400-600 eV | Plane-wave basis set quality |

| k-point Sampling | Γ-centered mesh, 3×3×1 to 11×11×11 | Brillouin zone integration |

| Convergence Threshold | 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻⁶ eV/atom | Electronic SCF convergence |

| Force Threshold | 0.01-0.05 eV/Å | Ionic relaxation convergence |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional | PBE, RPBE, B3LYP, HSE | Electron exchange-correlation treatment |

| Pseudopotential | PAW, US, norm-conserving | Core-electron treatment |

Advanced Computational Approaches

While DFT remains the workhorse for d-band center calculations, advanced computational methods are emerging to address accuracy and scalability limitations. Coupled-cluster theory (CCSD(T)) is considered the gold standard of quantum chemistry, providing highly accurate results that closely match experimental data [9]. However, its computational expense traditionally limited applications to small molecules.

Recent advances combine machine learning with computational chemistry to overcome these constraints. Neural network architectures like the Multi-task Electronic Hamiltonian network (MEHnet) can extract multiple electronic properties from CCSD(T) calculations with significantly improved computational efficiency [9]. These models utilize E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks where nodes represent atoms and edges represent bonds, incorporating physics principles directly into the algorithm [9].

For high-throughput screening, generative diffusion models like dBandDiff have been developed specifically for inverse materials design guided by d-band center targets [7]. These models can generate novel crystal structures conditioned on desired d-band center values and space group symmetry, dramatically accelerating the discovery of materials with tailored catalytic properties [7].

Correlation with Catalytic Properties and Experimental Validation

Adsorption Energy Relationships

The predictive power of d-band center theory primarily stems from its correlation with adsorption energies of reaction intermediates on catalyst surfaces. Extensive theoretical and computational studies have demonstrated that a higher d-band center—closer to the Fermi level—correlates with stronger bonding interactions between the d orbitals of transition metals and the s or p orbitals of adsorbates [7]. This leads to increased adsorption strength, while a lower d-band center—further below the Fermi level—results in weaker interactions due to the increased population of anti-bonding states, thereby reducing adsorption energies [7].

This fundamental relationship has been validated across diverse catalytic systems. In transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), adsorption energies of various transition metal adatoms show consistent periodic trends that correlate with electronic structure descriptors derived from d-band theory [10]. The relative order of adsorption energies remains consistent across different TMD substrates, with each adsorbate displaying similar trends in adsorption strength, indicating minimal dependence on the identity of the cation or anion in the TMD [10].

The physical origin of this correlation lies in the orbital hybridization and electronic filling effects. When the d-band center is closer to the Fermi level, the anti-bonding states shift above the Fermi level and remain unoccupied, resulting in stronger net bonding [5]. Conversely, when the d-band center is lower, the anti-bonding states become partially occupied, weakening the overall adsorption bond [5].

Catalytic Activity Descriptors

Beyond adsorption energies, the d-band center serves as a robust descriptor for overall catalytic activity across numerous reactions central to sustainable energy technologies. In water electrolysis, precisely adjusting the d-band center position on catalyst surfaces significantly improves catalytic activity for both the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER), while positively impacting long-term stability [6].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for catalyst development using d-band center theory:

Diagram 2: Catalyst development workflow using d-band center theory as a guiding descriptor, showing the iterative feedback between computation and experiment.

The theory has been successfully applied to optimize catalysts for key reactions including:

- Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER): Critical for water splitting systems [6] [7]

- Carbon Dioxide Reduction Reaction (CO₂RR): For sustainable fuel production [7]

- Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER): For clean hydrogen generation [6] [7]

- Nitrogen Fixation Reaction: For sustainable ammonia synthesis [7]

In each case, researchers have effectively controlled catalytic activity by strategically tuning the d-band center or used it to explain the reaction activity of materials [7].

Strategic Modulation of d-Band Center

Primary Regulation Strategies

The practical utility of d-band center theory extends beyond predictive capabilities to active catalyst design through strategic modulation of the d-band center position. Several primary strategies have been developed to systematically control εd:

Alloying: Combining transition metals with different electronegativities and d-band characteristics creates ligand effects that shift the d-band center position. For instance, in Rh-P nanoparticles, phosphorus content directly modulates the d-band center, enabling precise alignment with homogeneous Rh-phosphine complexes for hydroformylation applications [11].

Strain Engineering: Applying tensile or compressive strain to catalyst surfaces alters interatomic distances and orbital overlap, directly affecting d-band width and center position. Tensile strain typically narrows the d-band and raises the d-band center, strengthening adsorbate binding [6].

Nanostructuring: Creating low-coordination sites through nanoscale morphology control selectively tunes the d-band center of surface atoms. Coordination number reduction generally shifts the d-band center upward, enhancing reactivity at edge and corner sites [6].

Heteroatom Doping: Introducing foreign atoms into the catalyst lattice perturbs the local electronic environment. For example, exogenous nitrogen dopants in carbon-supported CoP systematically modulate d-band centers to boost ampere-level hydrogen evolution reaction [6].

Defect Engineering: Creating vacancies, particularly anion vacancies in compounds, alters local electron density and coordination environments. In transition metal dichalcogenides, chalcogen vacancies create under-coordinated cations that modify the electronic environment for adsorbate interactions [10].

Table: d-Band Center Modulation Strategies and Effects

| Strategy | Mechanism | Typical εd Shift | Impact on Adsorption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alloying (Ligand Effect) | Electron donation/withdrawal through heterometallic bonding | ±0.1-0.8 eV | Weakening or strengthening based on element electronegativity |

| Strain Engineering | Modification of interatomic distances and bandwidth | ±0.1-0.5 eV | Tensile strain typically strengthens adsorption |

| Nanostructuring | Creation of low-coordination sites | +0.2-1.0 eV (low-CN sites) | Generally strengthens adsorption at edges/steps |

| Heteroatom Doping | Local electronic structure perturbation | ±0.1-0.6 eV | Direction and magnitude depend on dopant character |

| Defect Engineering | Creation of unsaturated sites with modified electron density | +0.3-1.2 eV | Typically strengthens adsorption at defect sites |

Emerging Approaches

Beyond these established methods, innovative approaches continue to emerge. Interface engineering in heterostructures creates electronic interactions that collectively tune d-band centers through interfacial charge transfer [6]. In S-type heterojunction interface structures, electric field regulation of the d-band center significantly enhances photocatalytic CO₂ reduction to CH₄ [7].

Machine learning-guided design represents a paradigm shift in d-band center optimization. Generative models like dBandDiff enable inverse design of materials with target d-band center values, dramatically accelerating the discovery process [7]. When tasked with identifying novel materials with a d-band center of 0 eV (associated with strong adsorption capability), this approach successfully identified 17 reasonable materials from 90 generated structures whose computed d-band centers lay within ±0.25 eV of the target [7].

Applications Across Catalytic Systems

Water Electrolysis Catalysts

The d-band center theory has become an indispensable tool in designing advanced catalysts for water electrolysis, a key technology for sustainable hydrogen production. By adjusting the position of the d-band center on catalyst surfaces, researchers can effectively control the activity of both the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) at the cathode and the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) at the anode, thereby improving overall energy conversion efficiency [6].

Specific applications include:

- Enhancing d-band center modulation in carbon-supported CoP via exogenous nitrogen dopants for boosted ampere-level HER [6]

- Optimizing dp band centers as efficient active sites for solar energy conversion into H₂ by tuning surface atomic arrangement [6]

- Manipulating d-band centers of bimetallic FeNi catalysts derived from layered double hydroxides for selective electrocatalytic reduction of nitrates [6]

- Interfaces coupling of Co₈FeS₈-Fe₅C₂ with elevated d-band center for efficient water oxidation catalysis [6]

These applications demonstrate how d-band center theory provides systematic predictive capabilities for evaluating and optimizing electrocatalytic performance, offering essential theoretical support for creating efficient and stable water electrolysis catalysts [6].

Unifying Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysis

A significant advancement in d-band center application is the creation of unifying principles that bridge molecular-level reactivity in homogeneous catalysts with the durability and separability of heterogeneous systems. Recent research has established a computation-guided framework for rationally designing heterogeneous nanoparticles that emulate the catalytic properties of homogeneous catalysts [11].

By employing the d-band center as a transferable electronic descriptor, researchers have successfully aligned the electronic structure of Rh-P nanoparticles with benchmark Rh-phosphine complexes, enabling predictive control over hydroformylation activity [11]. This approach established a strong quantitative correlation between the deviation in d-band center and catalytic activity (R² = 0.994) [11]. Experimental evaluation revealed that Rh₃P, identified as the optimal composition through electronic structure matching, exhibited superior catalytic activity with a reaction rate of 13,357 h⁻¹, representing a 25% increase over the state-of-the-art RhP nanoparticle system [11].

This work establishes a generalizable framework for electronically guided catalyst design at the molecular level, demonstrating how d-band center alignment can transcend traditional boundaries in catalytic systems [11].

Research Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

The experimental and computational investigation of d-band centers requires specialized methodologies and analytical approaches. The following toolkit outlines essential components for research in this field:

Table: Essential Research Toolkit for d-Band Center Investigations

| Tool Category | Specific Methods/Reagents | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Software | Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) [7], Quantum Espresso [8], Amsterdam Density Functional (ADF) [12] | DFT calculations for electronic structure determination |

| Electronic Structure Methods | Projected Density of States (PDOS) [7], Density Functional Theory (DFT) [7], DFT+U [8] | Calculation of d-band center positions and electronic properties |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Multi-task Electronic Hamiltonian network (MEHnet) [9], dBandDiff generative model [7] | Accelerated prediction and inverse design of materials |

| Experimental Characterization | X-ray emission spectroscopy [5], X-ray absorption spectroscopy [5], Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) [8] | Experimental validation of electronic structure predictions |

| Catalytic Testing | Electrochemical water splitting cells [6], Hydroformylation reactors [11], Memristive switching devices [10] | Performance evaluation of designed catalysts |

| Data Analysis | Bader charge analysis [10], Crystal orbital Hamiltonian population (COHP) [12], Neural network uncertainty quantification [13] | Interpretation of electronic structure and bonding interactions |

The d-band center theory has established itself as a foundational electronic structure descriptor with remarkable predictive power for transition metal catalytic properties. From its origins in fundamental surface science to its current applications in sustainable energy technologies, this theory provides a crucial link between electronic structure and catalytic function. The continued refinement of computational methods, particularly through machine learning acceleration and advanced electronic structure calculations, promises to enhance both the accuracy and scope of d-band center predictions.

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas. First, improving the applicability and accuracy of theoretical models in complex systems, such as strongly correlated oxides and multicomponent alloys, remains a priority [6]. Second, the integration of d-band center theory with high-throughput computational screening and generative models will accelerate the discovery of novel catalytic materials with tailored properties [7]. Finally, extending these principles to dynamic catalysis under operating conditions represents the frontier of in situ and operando catalyst design.

As computational power increases and methods refine, the d-band center theory will continue to evolve from a descriptive model to a predictive framework capable of guiding the atomic-scale design of next-generation catalysts. This progression will be essential for addressing global energy challenges through the development of efficient, stable, and earth-abundant catalytic materials for sustainable energy conversion and storage.

The rational design of advanced oxide catalysts necessitates robust descriptors that bridge electronic structure and catalytic activity. While the d-band center model has long been a cornerstone for transition metal catalysis, this whitepaper examines the emerging recognition of the oxygen p-band center as a potent and often more universal descriptor for oxide-based electrocatalysts, particularly for the oxygen evolution reaction (OER). We delve into the theoretical foundation of this descriptor, present quantitative data validating its predictive power across diverse oxide families, and detail experimental protocols for its measurement. By integrating the p-band center into a broader descriptor framework, this guide provides researchers with the conceptual tools and practical methodologies to accelerate the design of next-generation catalytic materials.

The development of efficient electrocatalysts for sustainable energy applications, such as water splitting, is fundamentally limited by sluggish reaction kinetics, particularly those of the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) [14]. Overcoming this challenge requires a shift from Edisonian trial-and-error approaches to rational design based on a deep understanding of structure-activity relationships. Electronic structure descriptors serve as a crucial link in this process, providing a quantitative metric that connects a catalyst's intrinsic electronic properties to its observed catalytic performance[cite:10].

For decades, the d-band center model has been exceptionally successful in predicting trends in surface reactivity for transition metals and their alloys[cite:2][cite:5]. This model posits that the average energy of the d-band states relative to the Fermi level dictates the strength of adsorbate binding. However, its predictive power diminishes for metal oxides, where oxygen anions often play a critical, direct role in the catalytic mechanism[cite:2][cite:6]. In these systems, the valence electrons in the p-bands of non-metals are crucial for bond formation and cleavage during catalysis[cite:1]. This limitation of the d-band model has catalyzed the search for more comprehensive descriptors, leading to the emergence of the oxygen p-band center (( \varepsilon_p )) as a key electronic parameter for understanding and predicting the activity of oxide catalysts[cite:2][cite:6].

Theoretical Foundation: From the d-Band to the p-Band

The Established d-Band Center Model

The d-band center theory, formalized by Nørskov and colleagues, provides a simple yet powerful framework for explaining adsorption trends on transition metal surfaces[cite:2][cite:5]. It states that the strength of adsorbate-surface bonding is largely determined by the coupling between the adsorbate states and the metal d-states. A higher d-band center (closer to the Fermi level) leads to stronger adsorbate binding due to the upward shift of anti-bonding states, while a lower d-band center results in weaker binding[cite:5]. This descriptor has been widely used to rationalize catalytic activity across various reactions, including the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) on platinum-based intermetallics[cite:9].

The Oxygen p-Band Center Descriptor

In metal oxides, the oxygen 2p orbitals contribute significantly to the valence band edge and actively participate in surface reactions. The oxygen p-band center descriptor, denoted as ( \bar{\varepsilon}{2p} ), is defined as the average energy of the oxygen 2p-projected density of states (PDOS)[cite:2]. A key theoretical advance demonstrated that ( \bar{\varepsilon}{2p} ) robustly correlates with the reactivity of surface oxygen atoms across both metal and metal-oxide surfaces[cite:2].

The underlying physical principle is that the energy of the O 2p-states influences the charge transfer and covalency in metal-oxygen bonds, which in turn affects the binding strength of oxygen-containing intermediates (e.g., *O, *OH, *OOH) critical for the OER[cite:2][cite:6]. A higher ( \bar{\varepsilon}_{2p} ) (closer to the Fermi level) generally corresponds to stronger oxygen intermediate binding and altered reaction barriers, providing a direct electronic handle on catalytic activity.

Figure 1: The logical relationship between electronic descriptors and catalytic performance. Both the metal d-band center and oxygen p-band center directly influence the adsorption energies of reaction intermediates, which ultimately determines the overall catalytic activity.

Quantitative Validation: The p-Band Center as an Activity Predictor

The predictive power of the oxygen p-band center is best demonstrated through quantitative relationships with key catalytic metrics. The following table summarizes its role as a descriptor across different material classes.

Table 1: The Oxygen p-Band Center as a Descriptor in Different Catalytic Systems

| Material System | Reaction | Correlation | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metals & Metal Oxides | OER | Linear correlation between ( \bar{\varepsilon}{2p} ) and ( \Delta EO - \Delta E_{OH} ) | A robust, site-specific descriptor for surface oxygen reactivity across different materials and binding sites. | [cite:2] |

| Amorphous Ni-Fe-B Alloys | OER | Decreased energy difference between d- and p-band centers (( \Delta E_{d-p} )) lowers OER overpotential. | Compositional tuning optimizes ( \Delta E_{d-p} ), enhancing intermediate interactions and boosting activity. | [cite:1] |

| Perovskite Oxides | OER | Site-projected ( \varepsilon_p ) correlates with OER intermediate binding energies. | Local coordination environment strongly influences the ( \varepsilon_p ), enabling atom-by-atom design. | [cite:6] |

These studies establish the p-band center not merely as an alternative to the d-band model, but as a crucial complementary—and sometimes superior—descriptor for reactions involving oxygen intermediates. For instance, research on amorphous Ni-Fe-B alloys highlights the importance of considering the d- and p-band centers collectively. In this system, manipulating the composition to reduce the energy difference between the d- and p-band centers (( \Delta E_{d-p} )) was found to optimize interactions with catalytic intermediates and promote the formation of highly active oxidized Ni4+ species, leading to a lower energy barrier for the OER[cite:1].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Computational Determination of the p-Band Center

Density functional theory (DFT) is the primary tool for calculating the oxygen p-band center. The standard workflow is as follows:

- Structure Optimization: First, the bulk and/or surface structure of the oxide catalyst is relaxed to its ground-state geometry.

- Electronic Structure Calculation: A single-point calculation is performed on the optimized structure to obtain the electronic density of states (DOS).

- Projected DOS (PDOS) Analysis: The total DOS is projected onto the atomic orbitals of the surface oxygen atoms to obtain the O 2p-projected DOS.

- Descriptor Extraction: The p-band center (( \bar{\varepsilon}{2p} )) is calculated as the first moment (weighted average energy) of the O 2p-PDOS, typically using the formula: ( \bar{\varepsilon}{2p} = \frac{\int{-\infty}^{+\infty} E \cdot \rho{2p}(E) dE}{\int{-\infty}^{+\infty} \rho{2p}(E) dE} ) where ( \rho_{2p}(E) ) is the O 2p-PDOS.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Solutions for Theoretical and Experimental Studies

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function / Description | Application Context | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | A computational quantum mechanical method for modeling the electronic structure of materials. | Calculating adsorption energies, electronic density of states, and descriptor values (e.g., ( \varepsilond ), ( \varepsilonp )). | |

| Projected Density of States (PDOS) | A decomposition of the total DOS into contributions from specific atomic orbitals. | Isolating the contribution of oxygen 2p orbitals to determine ( \bar{\varepsilon}_{2p} ). | |

| Soft X-ray Spectroscopy | An experimental technique for probing the electronic structure of materials, including valence band states. | Experimentally validating computed electronic structure features like the O 2p-band. | [cite:1] |

| Machine Learning (ML) Models | Graph-based neural networks trained on DFT data to predict site-specific properties from local atomic structure. | Rapidly predicting ( \varepsilon_p ) and binding energies, bypassing expensive DFT calculations for high-throughput screening. | [cite:6] |

Experimental Probes and Synthesis Protocols

Linking the theoretical descriptor to real-world catalyst performance requires robust synthesis and characterization.

Synthesis of Amorphous Ni-Fe-B Alloys [cite:1]

- Method: Rapid chemical reduction.

- Procedure: Aqueous solutions of Ni(CH3COO)2·4H2O and FeSO4·9H2O are mixed in varying ratios. A NaBH4 solution is then rapidly added under stirring, leading to the instantaneous reduction of metal ions and the formation of an amorphous precipitate. The product is collected, washed, and dried.

- Key Insight: The Ni/Fe composition ratio is a critical parameter for tuning the electronic structure (( \Delta E_{d-p} )).

Experimental Characterization of Electronic Structure [cite:1]

- Technique: Soft X-ray spectroscopy (e.g., XPS, XAS).

- Application: This technique can provide experimental insights into the electronic structure of catalysts, including information relevant to the p-band. It is used to characterize the valence band and confirm the presence of key species, such as oxidized Ni4+ states in reconstructed (oxy)hydroxides.

Figure 2: A typical integrated workflow for developing and validating p-band center-designed catalysts, combining computation, synthesis, and characterization.

Advanced Applications and Emerging Trends

The application of the p-band center descriptor is expanding with the help of advanced computational methods.

- High-Entropy Alloys (HEAs) and Oxides: The vast compositional space of HEAs makes traditional descriptor screening infeasible. Recent studies show that the local chemical environment, including electronegativity, strongly regulates the d-band profile of the active center[cite:5]. This suggests that future models for complex multi-element systems will need to integrate p-band information with local environment descriptors for accurate activity prediction.

- Machine Learning Acceleration: The large design space of multi-metallic oxides necessitates efficient screening. Graph-based neural network models can now accurately predict site-dependent properties like the O 2p-band center and metal d-band center directly from atomic structure, without costly DFT calculations for every candidate[cite:6]. This enables the atom-by-atom design of surfaces with optimal descriptor values.

- Coupling Geometric and Electronic Effects: Beyond purely electronic descriptors, the most powerful design principles emerge from coupling geometric and electronic parameters. For instance, in diatomic catalysts for ORR, a "hot spot map" was constructed using the geometric distance between metal atoms and the electronic magnetic moment as coupled descriptors for rational design[cite:7].

The oxygen p-band center has firmly established itself as a universal and powerful descriptor for the rational design of oxide-based electrocatalysts. It provides a critical electronic structure perspective that complements and, in many oxide systems, surpasses the traditional d-band model. By quantitatively linking the energy of oxygen p-states to catalytic activity—especially for the OER—this descriptor offers a clear path for tailoring material properties.

The future of descriptor-based catalyst design lies in the multi-scale and multi-descriptor approach. Integrating the p-band center with other parameters (e.g., d-band center, geometric factors, local coordination) and leveraging machine learning to navigate vast compositional spaces will be essential. This integrated framework, firmly rooted in electronic structure theory, promises to accelerate the discovery and development of high-performance catalytic materials for a sustainable energy future.

In the pursuit of rationally designing advanced catalytic materials, researchers are increasingly moving beyond traditional geometric descriptors to leverage more fundamental electronic structure characteristics. Among the most promising developments in this domain are descriptors derived from the moments of the electronic density-of-states (DOS). These moments provide a robust and physically transparent means of characterizing local atomic environments by encoding information about both the immediate chemical coordination and longer-range atomic arrangements. The significance of these descriptors lies in their direct relationship to the electronic structure features that govern chemical bonding and reactivity—particularly the d-band properties of transition metal catalysts. For researchers engaged in catalyst design, moments-based descriptors offer a powerful framework for navigating vast compositional spaces, such as those presented by high-entropy alloys, where the intricate local chemical environment profoundly influences catalytic behavior.

Theoretical Foundations of DOS Moments

Mathematical Definition and Physical Interpretation

The moments of the electronic density-of-states provide a quantitative method for characterizing the distribution of electronic states in a material. Mathematically, the n-th moment of the DOS for orbital α of atom i is defined as:

[ \mu{i\alpha}^{(n)} = \int E^n n{i\alpha}(E)dE ]

where (n_{i\alpha}(E)) is the projected density of states [15]. According to the moments theorem, these mathematical constructs are directly related to the crystal structure through self-returning paths of electrons within the atomic lattice [15]. Each successive moment captures increasingly longer-range structural information, making the moments series an effective multi-scale descriptor of the local atomic environment.

The first few moments possess distinct physical interpretations that provide intuitive insight into material properties:

- Zeroth Moment ((\mu^{(0)})): Represents the total number of electronic states, serving as a normalization factor.

- First Moment ((\mu^{(1)})): Corresponds to the center of gravity of the DOS, indicating the average energy level.

- Second Moment ((\mu^{(2)})): Relates to the root-mean-square width of the DOS, primarily determined by the number and distance to nearest neighbors.

- Third Moment ((\mu^{(3)})): Describes the skewness or asymmetry of the DOS distribution.

- Fourth Moment ((\mu^{(4)})): Characterizes the bimodality or peak separation within the DOS [15].

Table 1: Physical Interpretation of DOS Moments

| Moment | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance | Structural Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeroth ((\mu^{(0)})) | (\int n_{i\alpha}(E)dE) | Total number of states | Normalization constant |

| First ((\mu^{(1)})) | (\int E n_{i\alpha}(E)dE) | Center of gravity | Average energy level |

| Second ((\mu^{(2)})) | (\int E^2 n_{i\alpha}(E)dE) | RMS width | Nearest-neighbor coordination |

| Third ((\mu^{(3)})) | (\int E^3 n_{i\alpha}(E)dE) | Skewness | Asymmetry in bonding |

| Fourth ((\mu^{(4)})) | (\int E^4 n_{i\alpha}(E)dE) | Bimodality | Peak separation in DOS |

Relationship to Local Atomic Environment

The connection between DOS moments and local atomic structure emerges from their computation via tight-binding Hamiltonian matrix elements. The n-th moment can be expressed as:

[ \mu{i\alpha}^{(n)} = \langle i\alpha|\hat{H}^n|i\alpha\rangle = \sum{j1\beta1...j{n-1}\beta{n-1}} H{i\alpha j1\beta1} H{j1\beta1 j2\beta2} ... H{j{n-1}\beta_{n-1}i\alpha ]

This formulation reveals that the n-th moment encompasses all self-returning paths of length n that begin and end at orbital α of atom i [15]. Each path incorporates structural information through the Hamiltonian matrix elements (H_{i\alpha j\beta}), which depend on the chemical identity of atoms i and j, their separation distance, and the bonding angles between them. Consequently, the second moment primarily reflects the immediate coordination shell, while higher moments progressively incorporate information from more distant atomic neighbors, creating a hierarchical description of the atomic environment.

Computational Analysis Methods

Calculation Protocols and Workflows

The computational determination of DOS moments typically follows a structured workflow that connects first-principles calculations with moment analysis:

Diagram 1: Computational workflow for DOS moments analysis

First-Principles Calculations: The process begins with density functional theory (DFT) calculations of the target material system. For accurate DOS computations, particular attention must be paid to k-point sampling—insufficient sampling can result in missing DOS features in energy intervals where bands are present [16]. The SCF convergence criteria and basis set selection must be carefully chosen to ensure electronic structure accuracy.

Projected DOS Calculation: Following the DFT calculation, the projected density of states (PDOS) is computed for relevant atomic orbitals. For catalyst applications, this typically involves d-orbitals of transition metal centers. The PDOS calculation may employ Gaussian broadening or the tetrahedron method for energy interpolation [17]. The energy range should be selected to capture all relevant electronic states, typically from several eV below the Fermi level to above it.

Tight-Binding Parameterization: For moments analysis, a tight-binding Hamiltonian is parameterized, often using a canonical d-valent tight-binding model for transition metal systems [15]. The Hamiltonian matrix elements (H_{i\alpha j\beta}) are determined in two-center approximation, with parameters fitted to reproduce DFT band structures or derived from first principles.

Moments Computation: Finally, the moments are calculated according to the moments theorem using the tight-binding Hamiltonian. The BOPfox software package implements this functionality through analytic bond-order potential methods [15]. For meaningful comparison across different structures or elements, moments are typically normalized by the average second moment to separate volume changes from internal relaxations [15].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for DOS Moments Analysis

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Application in Descriptor Development |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Codes (VASP, QuantumATK) | First-principles electronic structure calculation | Provides fundamental DOS and PDOS data for target materials |

| BOPfox | Bond-order potential and moments calculation | Computes moments from tight-binding Hamiltonian |

| Custom Python Scripts | Descriptor implementation and analysis | Constructs moments-based descriptors and similarity metrics |

| Tight-Binding Parameter Sets | Hamiltonian definition | Enables moments computation for specific material systems |

Applications in Materials Characterization

Local Atomic Environment Descriptors

Moments of the DOS have demonstrated significant utility as descriptors for characterizing local atomic environments in complex materials. The low-dimensional representation of atomic structure provided by moments enables effective classification of different coordination environments. Research has shown that a moments-descriptor projecting the space of local atomic environments onto a 2-D map can effectively separate various atomic environments while capturing their connections [18]. The distances within such maps correlate with energy differences between local atomic environments, providing a structural similarity metric with thermodynamic relevance.

The hierarchical nature of moments makes them particularly valuable for analyzing complex intermetallic compounds. For topologically close-packed (TCP) phases, the second moment primarily captures volume variations of unit cells and atomic coordination polyhedra, while higher moments reveal changes in longer-ranged coordination shells due to internal relaxations [15]. This multi-scale sensitivity enables moments to detect subtle structural variations that might be overlooked by geometric descriptors alone.

DOS Similarity Metrics for Materials Discovery

Beyond direct moments analysis, DOS-derived similarity metrics have emerged as powerful tools for materials discovery and classification. Recent research has developed a tunable DOS fingerprint that encodes the DOS as a binary-valued two-dimensional map, enabling quantitative similarity assessment between materials [19]. This approach addresses a key limitation of earlier DOS representations: the equal weighting of contributions from all energy regions regardless of their physical significance.

The DOS fingerprint generation process involves:

- Energy Axis Discretization: The DOS is integrated over a series of intervals with variable widths, creating finer discretization near a reference energy (typically the Fermi level) and coarser discretization farther away.

- Histogram Generation: The integrated DOS values form a histogram that accentuates features in electronically relevant regions.

- Raster Image Conversion: The histogram is converted to a binary raster image by discretizing each column into pixels, with the number of filled pixels determined by the integrated DOS value.

- Similarity Quantification: The similarity between two materials is computed using the Tanimoto coefficient applied to their binary fingerprint vectors [19].

This DOS similarity descriptor has been successfully applied to cluster two-dimensional materials in the Computational 2D Materials Database (C2DB), identifying groups with similar electronic properties and revealing unexpected relationships between structurally dissimilar materials [19].

Implementation in Catalyst Design

Electronic Descriptors for High-Entropy Alloys

The application of moments-derived descriptors has shown particular promise in the design of high-entropy alloy (HEA) catalysts, where the complex local chemical environment presents challenges for traditional descriptor approaches. Recent research on noble-metal HEA electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reactions has demonstrated that conventional d-band center descriptors ((ε_d)) show weak correlation with adsorption energies on HEA surfaces due to their failure to fully capture environmental effects [20].

To address this limitation, a new descriptor incorporating both the d-band filling of the active center ((fd^{Metal})) and the neighborhood electronegativity ((\bar{\chi}N)) has been developed:

[ \Omega = fd^{Metal} + \alpha\bar{\chi}N ]

This descriptor effectively integrates the d-band profiles of the active center (first-order response) with electronic perturbations from the complex chemical environment (second-order response) [20]. The combination accurately predicts adsorption energies of small molecular species on noble-metal HEA surfaces and has been used to establish activity maps across nine noble-metal elements, identifying Pd-rich and Ir-rich alloys as promising candidates for optimal electrocatalysts.

Experimental Validation and Performance

The predictive capability of electronic structure descriptors based on DOS moments has been validated through both computational and experimental studies. For HEA catalysts, the proposed descriptor (\Omega) shows strong correlation with oxygen adsorption energies calculated using DFT across a dataset of 8170 adsorption systems [20]. This robust correlation enables rapid screening of HEA compositions without requiring exhaustive DFT calculations for every possible local environment.

The effectiveness of these descriptors stems from their physical basis in the electronic structure, particularly their connection to bond-order potential theory, which establishes a direct relationship between moments and bond energies [15]. By capturing the essential physics of chemical bonding across diverse local environments, moments-based descriptors provide a transferable framework for catalyst design that extends beyond specific material classes.

Advanced Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed Computational Methodology

DFT Calculation Parameters: For reliable moments analysis, DFT calculations should employ sufficiently dense k-point grids to ensure accurate DOS sampling. A common issue in DOS calculations is missing DOS in energy intervals with bands but no computed DOS, which typically results from insufficient k-space sampling [16]. Projected DOS calculations should be performed with appropriate energy ranges (typically -10 eV to +10 eV relative to Fermi level) and energy steps (default ~0.005 Hartree or ~0.136 eV) [16].

Tight-Binding Framework: The moments analysis typically employs a canonical tight-binding model with d-valent parameters for transition metal systems [15]. The Hamiltonian matrix elements are computed in two-center approximation with distance-dependent parameters following canonical forms. For non-transition metal systems, appropriate sp or spd models should be employed to capture the relevant bonding.

Moments Normalization: To enable comparison across different structures and elements, moments should be normalized by the average second moment. This scaling effectively separates volume changes from internal relaxations, following the structural energy difference theorem [15]. The normalized moments highlight differences in atomic arrangement independent of overall volume variations.

Descriptor Implementation Protocol

Moments Descriptor Construction:

- Compute the first four moments for each atomic site in the structure.

- Normalize moments by the average second moment across all sites.

- For environment characterization, compute the mean and variance of moments across equivalent sites.

- Project the moments vector onto a low-dimensional space using PCA if necessary for specific applications.

Similarity Assessment:

- Generate DOS fingerprints using the variable-width energy discretization protocol.

- Compute similarity matrix using Tanimoto coefficients between fingerprint vectors.

- Apply clustering algorithms (e.g., hierarchical clustering) to identify material groups.

- Validate clusters using auxiliary descriptors for composition and crystal structure.

Diagram 2: Logical relationship between atomic environment, DOS moments, and material properties

Moments of the density of states and their derived descriptors represent a powerful approach for characterizing local atomic environments and predicting material properties in catalyst design. Their strong physical foundation in electronic structure theory, multi-scale sensitivity to atomic arrangements, and computational efficiency make them particularly valuable for navigating complex material spaces such as high-entropy alloys. As computational materials science continues to generate increasingly large datasets, the development and application of sophisticated electronic structure descriptors will play a crucial role in unlocking structure-property relationships and accelerating the discovery of next-generation catalytic materials. The integration of these descriptors with machine learning approaches and high-throughput computational screening presents a promising path forward for rational catalyst design.

In the pursuit of rational materials design, descriptors serve as quantifiable fingerprints that bridge the fundamental properties of a material with its macroscopic performance. For researchers in catalysis and drug development, selecting the appropriate class of descriptors is a critical strategic decision that directly impacts the success of predictive modeling and high-throughput screening efforts. This review provides a technical guide to the landscape of descriptors, framing their evolution and application within the specific context of electronic structure descriptors for catalyst design research. We dissect and compare three dominant paradigms: energy descriptors, which distill complex interactions into thermodynamic quantities; electronic descriptors, which probe the underlying electronic structure governing reactivity; and structural descriptors, which encode geometrical and topological information. By presenting a structured comparison of their theoretical foundations, computational methodologies, and practical applications, this review aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to navigate this complex field and select the optimal descriptors for their specific research challenges in catalysis and beyond.

Theoretical Foundations and Evolution of Descriptors

The development of descriptors has followed a clear evolutionary path, driven by the need to more accurately and efficiently predict material functionality. The earliest approaches, originating in the 1970s, relied on energy descriptors. Seminal work by Trasatti utilized the heat of hydrogen adsorption on different metals, plotted in volcano plots, to describe the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) [5]. This established the foundational principle that catalytic activity could be correlated with the thermodynamic energies of key reaction intermediates. This concept was later expanded by Nørskov et al., who used density functional theory (DFT) to calculate the stability of reaction intermediates in electrochemical processes [5]. The primary limitation of energy descriptors is the existence of "scaling relationships" between the adsorption free energies of different intermediates, which imposes inherent thermodynamic limitations on catalytic efficiency and can restrict their predictive power [5].

In the 1990s, a paradigm shift occurred with the introduction of electronic descriptors. Jens Nørskov and Bjørk Hammer's d-band center theory for transition metal catalysts demonstrated that the average energy of d-orbital states relative to the Fermi level could predict adsorbate bonding strength [5]. This provided a microscopic electronic perspective that energy descriptors lacked, offering a more fundamental explanation for catalytic activity and selectivity on metal surfaces. Electronic descriptors effectively capture the geometric and electronic properties of molecules and crystals, offering improved computational efficiency and helping to mitigate the limitations posed by scaling relationships.

The most recent evolution involves data-driven descriptors powered by machine learning (ML). These descriptors integrate high-throughput screening, ML, and computational chemistry to establish complex, often non-linear, relationships between a material's composition, structure, and its properties [5]. For instance, graph-based descriptors represent crystal structures as networks of atoms (nodes) and bonds (edges), enabling a highly detailed and flexible description that can be augmented with advanced physical and chemical properties [21]. Similarly, atom-centered descriptors like the Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) provide a comprehensive representation of local atomic environments [21]. The rise of these sophisticated structural and data-driven descriptors marks a transition from relying on a single physical quantity to using high-dimensional feature vectors that provide a more holistic representation of a material for predictive modeling.

Comparative Analysis of Descriptor Approaches

The following tables provide a detailed comparison of the three primary descriptor classes, summarizing their core principles, key examples, and associated computational tools.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Descriptor Types: Energy, Electronic, and Structural

| Descriptor Class | Theoretical Basis | Key Examples | Primary Applications | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Descriptors | Sabatier principle, Thermodynamics, Scaling & Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) relationships [5]. | Adsorption free energy (e.g., ΔGH for HER [5], ΔGC2O2, ΔGOH for CORR [5]). | Predicting catalytic activity trends, Volcano plots, Assessing electrocatalytic performance [5]. | Computationally demanding for complex systems, Limited information on electronic structure, Constrained by scaling relationships [5]. |

| Electronic Descriptors | Electronic Structure Theory, Density of States. | d-band center (εd) [5], Molecular orbital energies (e.g., HOMO, LUMO) [22], Work function [23]. | Predicting adsorption strength on metal surfaces [5], Explaining catalyst selectivity, Band gap prediction [23]. | Can struggle with strongly correlated systems, Not always directly linked to experimentally measurable factors [5]. |

| Structural Descriptors | Chemical Graph Theory, Topology, Geometry. | Molecular: ~6,000 descriptors in alvaDesc (constitutional, topological, 3D-autocorrelation) [24]. Crystal: SOAP, MBTR, Graph descriptors [21]. | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR) [24], High-throughput virtual screening, Machine learning force fields (MLFF) [21]. | High dimensionality often requires feature reduction; Risk of being "black box" with low direct interpretability. |

Table 2: Computational Tools for Descriptor Calculation and Their Key Features

| Tool Name | Descriptor Types | Key Features & Scope | Target Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| alvaDesc [24] | Structural, Molecular | Calculates ~6,000 molecular descriptors and fingerprints; Includes drug-like indices (e.g., QED, LogP) and synthetic accessibility score. | Molecules, Salts, Ionic Liquids |

| E-Dragon [25] | Structural, Molecular | Remote electronic version of DRAGON; Provides >1,600 molecular descriptors from 20 logical blocks. | Molecules |

| DataWarrior [26] | Structural, Chemical Intelligence | Combines dynamic graphical views with chemical intelligence; Supports compound clustering and SAR table creation. | Chemical & Biological Data |

| Matminer [21] | Structural, Electronic, Compositional | Open-source Python library; Integrated with materials databases (e.g., Materials Project); Offers extensive pre-built descriptors for crystals. | Crystalline Materials |

| QUED Framework [22] | Electronic, Structural | "QUantum Electronic Descriptor" framework; Combines QM-derived electronic features with geometric descriptors using DFTB method. | Drug-like Molecules |

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of ML Models Using Engineered Descriptors

| Study Focus | Descriptor Engineering Approach | Machine Learning Model | Performance (R² / MAE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction of 2D Material Band Gap & Work Function [23] | Hybrid features from vectorized property matrices & empirical electronegativity. | Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | R²: 0.95 (Band Gap), 0.98 (Work Function); MAE: 0.16 eV (Band Gap), 0.10 eV (Work Function) |

| Automatic Descriptors Recognizer (ADR) [27] | Named Entity Recognition (NER) with MatBERT-BiLSTM-CRF model to extract descriptors from literature. | Not Specified (Feature extraction for ML) | Extracted 106,896 coarse-grained descriptors from 1,808 literature sources. |

| Quantum-Mechanical Descriptors for Property Prediction [22] | QUED framework combining QM properties (from DFTB) with geometric descriptors. | Kernel Ridge Regression, XGBoost | Enhanced prediction for physicochemical properties and biological endpoints (toxicity, lipophilicity). |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Workflow for Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) Descriptor Calculation

A contemporary, ML-accelerated protocol for calculating a novel energy descriptor, the Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED), for catalyst discovery in CO₂ to methanol conversion is detailed below [28].

- Search Space Selection: Identify metallic elements relevant to the catalytic process (e.g., from literature) that are also present in the Open Catalyst 2020 (OC20) database to ensure compatibility with ML force fields (MLFFs).

- Material Compilation: Query materials databases (e.g., Materials Project) for stable crystal structures of these elements and their bimetallic alloys. Perform DFT optimization on the bulk structures.

- Adsorbate Selection: Based on experimental and theoretical literature, identify key reaction intermediates (e.g., *H, *OH, *OCHO, *OCH₃ for CO₂ to methanol).

- Surface Generation & Relaxation: For each material, generate multiple surface facets (e.g., Miller indices from -2 to 2). Identify the most stable surface termination for each facet using the MLFF. Engineer surface-adsorbate configurations for these stable terminations.

- MLFF Optimization: Optimize all surface-adsorbate configurations using a pre-trained MLFF (e.g., Equiformer_V2 from the Open Catalyst Project) instead of DFT. This step provides a massive speed-up (factor of 10⁴ or more) while maintaining quantum mechanical accuracy.

- Validation and Data Cleaning: Benchmark the MLFF-predicted adsorption energies against explicit DFT calculations for a subset of materials and adsorbates to ensure reliability. The mean absolute error (MAE) for adsorption energies should be within an acceptable threshold (e.g., ~0.16 eV) [28].

- AED Construction & Analysis: For each material, aggregate the calculated adsorption energies across all facets, binding sites, and selected adsorbates to form the AED. Analyze the resulting distributions using unsupervised learning (e.g., hierarchical clustering with Wasserstein distance) to group catalysts with similar AED profiles and identify promising candidates [28].

Protocol for Constructing Vectorized Descriptors for 2D Materials

This protocol outlines the creation of hybrid, low-cost computational descriptors for predicting electronic properties of 2D materials, such as band gap and work function [23].

- Data Collection: Source a dataset of 2D materials with known properties, such as the Computational 2D Materials Database (C2DB).

- Base Descriptor Selection: Extract readily available database features (e.g., number of atoms, cell volume, formation heat).

- Empirical Descriptor Calculation: Calculate an empirical property for the molecule, such as electronegativity (χ) using the formula for a molecular formula AₐB₆C꜀: χ = (AᵃBᵇCᶜ)¹/⁽ᵃ⁺ᵇ⁺ᶜ⁾ [23].

- Property Matrix Construction: For target atomic properties with a strong physico-chemical relationship to the electronic structure (e.g., covalent radius, dipole polarizability, ionization energy), construct property matrices.

- For a molecule with n atoms, the property matrix Pᵢ = [aᵢⱼ] for i,j = 1 to n, where the operator Ĥ (e.g., addition, multiplication) is applied to the atomic property of atoms i and j to fill the matrix. This captures atom-atom pair interactions.

- Vectorization: Compute the eigenvalues (λ) for each symmetric property matrix (PᵢX = λX). The set of eigenvalues forms a "property vector" that represents the characteristic spectrum of the feature, flattening the matrix while retaining physical meaning.

- Feature Integration: Combine the ready-to-use database features, the empirical descriptor, and the vectorized property descriptors into a single set of hybrid features.

- Model Training and Prediction: Use this hybrid feature set to train tree-based ML models (e.g., XGBoost) for property prediction, which has been shown to achieve high accuracy (R² > 0.9) [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Software and Databases

The effective application of descriptors in research requires a suite of software tools and databases. The following table details key resources that constitute the essential toolkit for scientists working in this domain.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents: Software and Databases for Descriptor-Based Research

| Tool / Database Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Descriptor Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| alvaDesc [24] | Software | Calculates a wide range of molecular descriptors and fingerprints. | Primary tool for generating ~6,000 molecular descriptors for QSAR/QSPR in drug development. |

| Matminer [21] | Software Library | Provides a vast array of pre-built descriptors for crystalline materials. | Core resource for featurizing crystal structures in materials informatics; integrates with ML workflows. |

| E-Dragon [25] | Web Service | Calculates >1,600 molecular descriptors remotely. | Useful for quick descriptor calculation without local software installation, ideal for cheminformatics. |

| DataWarrior [26] | Software | Combines dynamic graphical visualization with chemical intelligence. | Used for interactive data analysis, visualization, and SAR studies on chemical datasets. |

| Open Catalyst Project (OC20) [28] | Database & Models | Provides datasets and pre-trained ML force fields for catalysis. | Critical resource for ML-accelerated calculation of energy descriptors like adsorption energies. |

| Materials Project (MP) [21] | Database | A vast database of computed crystal structures and properties. | Source for initial crystal structures and data for high-throughput screening and descriptor calculation. |

| Computational 2D Materials Database (C2DB) [23] | Database | Curated database of computed properties for 2D materials. | Provides reliable data for training and validating models predicting electronic structure properties. |

| QUED Framework [22] | Software Framework | Generates quantum-mechanical descriptors from semi-empirical calculations. | For researchers needing to incorporate electronic structure data into ML models for improved accuracy. |

The landscape of descriptors is rich and varied, with each class—energy, electronic, and structural—offering distinct advantages and facing specific limitations. The evolution from simple thermodynamic quantities to high-dimensional, data-driven representations reflects the growing complexity of challenges in catalyst design and drug development. Energy descriptors provide a direct link to activity, electronic descriptors offer fundamental insight, and modern structural descriptors enable the power of machine learning on complex systems. The future of descriptor development lies in the intelligent integration of these approaches, creating hybrid models that are not only predictive but also physically interpretable. As machine learning and computational power continue to advance, the role of sophisticated, multi-faceted descriptors will only become more central, accelerating the discovery and optimization of next-generation materials and therapeutic compounds.

How to Apply Electronic Descriptors: A Guide for Catalyst Design and Screening

In the quest for advanced catalysts for energy sustainability and chemical production, descriptor-based analysis provides a powerful framework for predicting catalytic activity and selectivity [29]. Key descriptors, such as the binding energies of reaction intermediates on catalyst surfaces, are derived from ab initio calculations, notably Density Functional Theory (DFT) [29]. High-throughput computational screening using these descriptors has successfully identified promising catalyst candidates; however, the high computational cost of DFT remains a significant bottleneck for exploring vast chemical spaces [29]. This whitepaper details a universal computational workflow for the accurate and efficient prediction of these crucial descriptors, leveraging advanced machine learning (ML) techniques to accelerate rational catalyst design.

Core Methodology: A Workflow for Descriptor Prediction

The accurate prediction of descriptors hinges on a robust computational workflow that integrates first-principles calculations with machine learning. The following diagram outlines this multi-stage process.

First-Principles Input from Density Functional Theory