From Code to Clinic: A Practical Framework for Validating Machine Learning Predictions with Experimental Results

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to bridging the gap between machine learning predictions and experimental validation.

From Code to Clinic: A Practical Framework for Validating Machine Learning Predictions with Experimental Results

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to bridging the gap between machine learning predictions and experimental validation. Covering foundational concepts, methodological applications, troubleshooting, and comparative analysis, it addresses the critical challenge of ensuring ML model robustness and reliability in biomedical research. Readers will gain actionable strategies for designing validation workflows, interpreting performance metrics, and translating computational forecasts into clinically actionable insights, with a focus on real-world case studies from recent literature.

The Critical Bridge: Why Validating ML Predictions is Non-Negotiable in Research

Model validation is the critical process of evaluating how well a machine learning model performs on unseen, real-world data, ensuring it generalizes effectively beyond what it has seen during training [1]. In scientific research, particularly in high-stakes fields like drug development, this process transcends mere technicality—it becomes a fundamental requirement for building trustworthy and reliable AI systems.

The core challenge that validation addresses is overfitting, a scenario where a model performs excellently on its training data but fails to generalize to new data because it has memorized the training set's noise and idiosyncrasies rather than learning the underlying patterns [2] [3]. A high accuracy score on a training dataset does not necessarily indicate a successful model; the true test comes when it encounters new, unseen data in the real world [2]. Model validation provides the framework for this test, serving as the essential bridge between theoretical model development and practical, real-world application [1].

Core Principles: From Goodness-of-Fit to Generalizability

The evolution of model evaluation criteria has shifted the focus from simple goodness-of-fit to a more robust emphasis on generalizability.

Goodness-of-Fit and Its Limitations

Descriptive adequacy, or goodness-of-fit, measures how well a model fits a specific set of empirical data using metrics like Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) or percent variance accounted for [4]. While a good fit is a necessary piece of evidence for model adequacy, it is an insufficient criterion for model selection because it fails to distinguish between fit to the underlying regularity and fit to the noise present in every dataset [4]. A model that is too complex can achieve a perfect fit by learning the experiment-specific noise, a phenomenon known as overfitting [4].

Generalizability as the Paramount Criterion

Generalizability evaluates how well a model, with its parameters held constant, predicts the statistics of future samples from the same underlying processes that generated an observed data sample [4]. It is considered the paramount criterion for model selection because it directly addresses the problem of overfitting. A model with high generalizability captures the underlying regularity in the data without being misled by transient noise [4]. This quality is assessed through proper validation strategies and robust evaluation metrics.

Table 1: Core Criteria for Model Evaluation

| Criterion | Definition | Primary Strength | Primary Weakness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goodness-of-Fit | Measures how well a model fits a specific set of observed data. | Quantifies model's ability to reproduce known data. | Does not distinguish between fit to regularity and fit to noise; promotes overfitting. |

| Generalizability | Measures how well a model predicts future observations from the same process. | Evaluates predictive accuracy on new data; guards against overfitting. | Requires careful validation design (e.g., data splitting, cross-validation). |

| Complexity | Measures the inherent flexibility of a model to fit diverse data patterns. | Helps assess if a model is unnecessarily complex. | Must be balanced with goodness-of-fit for optimal model selection. |

Diagram 1: The Model Validation Workflow. This process uses a validation set to provide an unbiased evaluation for hyperparameter tuning and model selection, ensuring the final model generalizes well.

Experimental Protocols for Robust Validation

Implementing a robust validation strategy requires meticulous experimental design. The following protocols are foundational to producing reliable and interpretable results.

Data Splitting Strategies

A fundamental step is partitioning the available data into distinct subsets to simulate the model's performance on unseen data [5] [3].

- Training Set: The largest portion (e.g., 70%) used to teach the model by adjusting its internal parameters [3].

- Validation Set: A separate subset (e.g., 15%) used to provide an unbiased evaluation during training, guiding hyperparameter tuning and other development decisions without leaking information from the test set [3].

- Test Set: A final holdout set (e.g., 15%) used only once, after model development is complete, to provide a final, unbiased estimate of the model's real-world performance [3].

Maintaining a strict separation between these sets is critical. Using the test set for iterative tuning can lead to an overoptimistic performance estimate, as the model effectively "learns" the test set [3].

Resampling and Cross-Validation Techniques

For limited data or to obtain more robust performance estimates, resampling techniques are essential [5] [3].

- K-Fold Cross-Validation: The dataset is randomly shuffled and split into k equal-sized groups (folds). The model is trained k times, each time using k-1 folds for training and the remaining fold for validation. The performance is averaged across all k runs [5]. This provides a more stable estimate of model performance.

- Stratified K-Fold: An enhancement of K-Fold that ensures each fold retains the same proportion of class labels as the original dataset. This is particularly important for classification tasks with imbalanced classes [5].

- Time-Based Split: For time-series or longitudinal data, a time-wise split must be used where the model is trained on past data and validated on future data. This preserves the temporal order and prevents data leakage from the future [5].

Case Study: Experimental Validation for Contamination Classification

A 2025 study in Scientific Reports on classifying contamination levels of high-voltage insulators provides a robust example of experimental validation [6].

- Objective: To validate machine learning models for automatically classifying insulator contamination levels (High, Moderate, Low) based on leakage current signals.

- Dataset: A meticulously developed dataset of leakage current for porcelain insulators with varying pollution levels under controlled laboratory conditions, incorporating environmental parameters like temperature and humidity to reflect real-world scenarios [6].

- Preprocessing & Feature Extraction: The raw leakage current data was preprocessed, and critical features were extracted from the time, frequency, and time-frequency domains. The most important features were identified and ranked [6].

- Models & Optimization: Four distinct ML models, including decision trees and neural networks, were trained. Bayesian optimization was used to tune their hyperparameters [6].

- Results: The models demonstrated exceptional performance, with accuracies consistently exceeding 98%. The study also provided a practical insight: decision tree-based models exhibited significantly faster training and optimization times compared to neural network counterparts [6].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML Validation

| Reagent / Tool Category | Example Tools / Libraries | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| General ML & Metrics | Scikit-learn | Provides standard ML metrics, resampling methods, and model training utilities. |

| Experiment Tracking | MLflow, Neptune.ai | Tracks experiments, logs parameters, metrics, and dataset versions for comparison. |

| Production ML Analysis | TensorFlow Model Analysis (TFMA) | Enables slice-based model evaluation to check performance across data segments. |

| Model & Data Drift | Evidently AI | Monitors model performance and data drift in production through visual dashboards. |

| Automated ML | PyCaret | Automates model validation and experiment tracking for rapid prototyping. |

Comparative Analysis of Validation Methods and Metrics

Selecting the right validation method and corresponding evaluation metric is contingent on the problem context, data structure, and business objective.

Model Selection Methods

Choosing between models requires methods that balance goodness-of-fit with complexity to maximize generalizability [4].

- Akaike Information Criterion (AIC): An estimate of the information loss when a model is used to represent the data-generating process. It penalizes model complexity but tends to select more complex models as dataset size increases. Formula:

AIC = -2 * ln(L) + 2K, where L is the maximum likelihood and K is the number of parameters [5] [4]. - Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC): Similar to AIC but imposes a stronger penalty for model complexity, especially with larger datasets. It is derived from Bayesian probability. Formula:

BIC = -2 * ln(L) + K * ln(N), where N is the number of data points [5] [4].

Performance Metrics Beyond Accuracy

Relying solely on accuracy can be misleading, especially for imbalanced datasets. A holistic view requires multiple metrics [1] [7].

For Classification:

- Precision: The proportion of positive predictions that were correct. Critical when the cost of false positives is high (e.g., in spam detection).

- Recall (Sensitivity): The proportion of actual positives correctly predicted. Crucial when missing a positive case is dangerous (e.g., in disease screening).

- F1 Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall. Provides a single metric for imbalanced dataset performance [1] [7].

- AUC-ROC: Measures the model's ability to separate classes across all possible classification thresholds [1].

For Regression:

- Mean Squared Error (MSE): The average of squared differences between predicted and actual values. Heavily penalizes large errors.

- R² Score: Indicates the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables [1].

Diagram 2: Decision Logic for Validation Design. The choice of strategy and metrics is driven by the problem context and the specific business or research goal.

Table 3: Comparison of Model Selection Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | Estimates information loss; penalizes number of parameters. | Easy to compute; versatile for many models. | Tends to select more complex models as N increases. | Model comparison when the goal is prediction. |

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | Derived from Bayesian probability; stronger penalty than AIC. | Consistent estimator; prefers simpler models for larger N. | Can oversimplify with very small datasets. | Selecting the true model among candidates. |

| Cross-Validation (e.g., K-Fold) | Directly estimates performance on unseen data via resampling. | Provides a robust, less biased performance estimate. | Computationally intensive for large k or complex models. | Most scenarios, especially with sufficient data. |

Advanced Considerations: Ensuring Real-World Reliability

For AI systems deployed in critical domains like drug development, validation must extend beyond standard performance metrics to include fairness, robustness, and security.

Ethical AI: Fairness and Bias Testing

AI must be fair, transparent, and compliant with regulations. Historical incidents, such as Amazon's AI hiring tool penalizing women's resumes, underscore the necessity of fairness testing [8].

- Testing Techniques:

- Demographic Parity: Ensuring predictions are balanced across different demographic groups.

- Equalized Odds: Verifying that true positive and false positive rates are similar across groups.

- Counterfactual Testing: Checking if changing a sensitive attribute (e.g., gender) unfairly alters the model's outcome [8].

Robustness and Security Validation

Models must be resilient to unexpected inputs and malicious attacks.

- Adversarial Testing: Introducing subtle, maliciously designed changes to inputs to test model resilience. For example, researchers tricked Tesla's self-driving AI by adding small stickers to a stop sign, causing it to be misread [8].

- Stress & Edge Case Testing: Pushing the model with inputs outside its training distribution, such as testing an autonomous vehicle's perception model in extreme weather conditions [8].

- Data Drift Detection: Monitoring and testing for changes in the input data distribution over time that can degrade model performance. This requires continuous validation in production systems [8] [1].

Model validation is the indispensable discipline that transforms a theoretical machine learning exercise into a reliable, real-world solution. It demands a shift in perspective from simply achieving high training accuracy to ensuring robust generalizability. This is accomplished through rigorous experimental protocols—judicious data splitting, resampling techniques like cross-validation, and the use of model selection criteria that reward simplicity and predictive power.

For researchers and scientists, particularly in fields like drug development, a comprehensive validation framework is non-negotiable. It must integrate not only classic performance metrics but also advanced testing for fairness, robustness, and security. By adhering to these principles, we build AI systems that are not only powerful but also trustworthy and ready to deliver on their promise in the most demanding environments.

In biomedical research, the transition from machine learning (ML) research to clinical application is fraught with peril when validation is inadequate. Validation metrics serve as the crucial bridge between algorithm development and real-world clinical implementation, actively shaping scientific progress by determining which methods are considered state-of-the-art [9]. When these metrics are chosen inadequately or implemented without understanding their limitations, the consequences extend far beyond academic circles—they can spark futile resource investment, obscure true scientific advancements, and potentially impact human health [9]. The complexity of biomedical data, characterized by high levels of uncertainty, biological variation, and often conflicting information of uncertain validity, makes robust validation particularly essential in this domain [10].

The fundamental challenge lies in the fact that the flexibility and predictive power of machine learning models come with inherent complexities that make them prone to misuse [11]. Without proper validation standards, research results become difficult to interpret, and potentially spurious conclusions can compromise the credibility of entire fields [11]. This comprehensive analysis examines the consequences of poor validation practices, compares validation methodologies, and provides a structured framework for enhancing validation quality in biomedical machine learning applications.

The Perils of Inadequate Validation: Consequences and Case Studies

Widespread Pitfalls in Current Practice

The biomedical machine learning landscape currently faces several critical validation challenges that undermine the reliability and clinical applicability of published models:

Metric Misapplication: Increasing evidence shows that validation metrics are often selected inadequately in image analysis and other biomedical applications [9]. This frequently stems from a mismatch between a metric's inherent mathematical properties and the underlying research question or dataset characteristics [9].

Propagation of Poor Practices: Historically grown validation practices are often not well-justified, with poor practices frequently propagated across studies. One remarkable example documented in literature is the widespread adoption of an incorrectly named and mathematically inconsistent metric for cell instance segmentation that persisted through multiple influential publications [9].

Insufficient External Validation: A comprehensive scoping review of ML in oncology revealed that despite high reported performance, most algorithms have yet to reach clinical practice, primarily due to subpar methodological reporting and validation standards [12]. Predictions modeled after specific cohorts can be misleading and non-generalizable to new case mixes [12].

Quantifying the Impact: Performance Degradation in Real-World Settings

Table 1: Performance Degradation in External Validation Studies

| Study Focus | Internal Validation Performance | External Validation Performance | Performance Decline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Expenditure Prediction [13] | RMSE: 0.91 METs (SenseWear/Polar H7) | RMSE: 1.22 METs (SenseWear Neural Network) | 34% increase in error |

| Physical Activity Classification [13] | 85.5% accuracy (SenseWear/Polar H7) | 80% accuracy (SenseWear Gradient Boost/Random Forest) | 5.5% absolute decrease |

| Fitbit Energy Estimation [13] | RMSE: 1.36 METs | N/A (increased error in out-of-sample validation) | Significant increase noted |

The performance degradation observed when models face external validation highlights the critical importance of rigorous testing beyond internal datasets. This phenomenon creates uncertainty regarding the generalizability of algorithms and poses significant challenges for their clinical implementation [13]. The decline in performance metrics when models encounter new data distributions represents one of the most tangible consequences of inadequate validation frameworks.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Methodologies

Machine Learning Algorithms in Biomedical Validation

Table 2: Comparison of ML Algorithm Performance in Biomedical Applications

| Algorithm Type | Common Applications in Biomedicine | Key Strengths | Validation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) | Medical image analysis, tumor detection [12] | High performance in image-based tasks [12] | Requires extensive external validation; multi-institutional collaboration recommended [12] |

| Random Forest & Gradient Boosting | Physical activity monitoring, energy expenditure prediction [13] | Superior performance for most wearable devices [13] | Tendency for performance degradation in out-of-sample validation [13] |

| Deep Learning Neural Networks (DLNN) | Landslide susceptibility mapping (comparative basis) [14] | Handles non-linear data with different scales; models complex relationships [14] | Outperforms conventional ML models in prediction accuracy [14] |

| Logistic Regression | Traditional statistical modeling [11] | Interpretable, familiar to clinical researchers | Often inadequate for big data complexity [11] |

Metric Selection Framework for Biomedical Applications

The selection of appropriate validation metrics must align with both the technical problem type and the clinical context:

Classification Problems: For classification tasks at image, object, or pixel level (encompassing image-level classification, semantic segmentation, object detection, and instance segmentation), metrics should include sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, area under the ROC curve, and calibration plots [9] [11].

Regression Problems: Continuous output problems, such as energy expenditure prediction or risk estimation, should report normalized root-mean-square error (RMSE) alongside clinical acceptability ranges [13] [11].

Clinical Utility Assessment: Beyond traditional metrics, models intended for clinical deployment require utility assessments that evaluate their impact on decision-making. One review of oncology models documented assessments involving 499 clinicians and 12 tools, finding improved clinician performance with AI assistance [12].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Validation

Recommended Validation Workflow

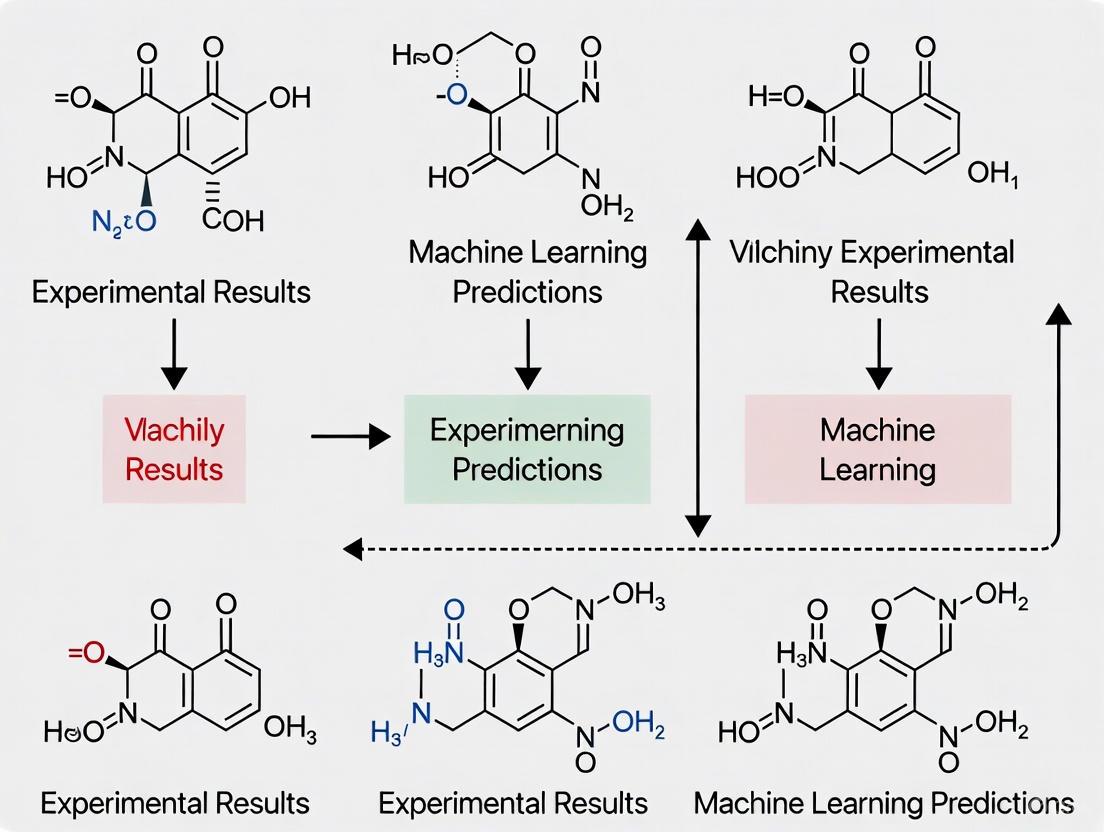

Figure 1: Comprehensive Validation Workflow for Biomedical ML Models

Essential Reporting Standards

Following established reporting guidelines ensures sufficient transparency for critical assessment of model validity:

Structured Abstracts: Must identify the study as introducing a predictive model, include objectives, data sources, performance metrics with confidence intervals, and conclusions stating practical value [11].

Methodology Details: Should define the prediction problem type (diagnostic, prognostic, prescriptive), determine retrospective vs. prospective design, explain practical costs of prediction errors, and specify validation strategies [11].

Data Documentation: Must describe data sources, inclusion/exclusion criteria, time span, handling of missing values, and basic statistics of the dataset, particularly the response variable distribution [11].

Model Specifications: Should report the number of independent variables, positive/negative examples for classification, candidate modeling techniques with justifications, and model selection strategy with performance metrics [11].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ML Validation in Biomedicine

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Techniques | Function in Validation Process |

|---|---|---|

| Validation Metrics | Sensitivity/Specificity, AUC-ROC, Calibration Plots [11] | Quantify model performance and reliability for clinical deployment |

| Statistical Validation Methods | K-fold Cross-Validation, Bootstrap, Leave-One-Subject-Out [13] | Ensure robust internal validation and mitigate overfitting |

| External Validation Frameworks | Multi-institutional Collaboration, Temporal Validation [12] | Assess model generalizability across diverse populations and settings |

| Clinical Utility Assessment | Clinician Workflow Integration Studies [12] | Evaluate real-world impact on decision-making and patient outcomes |

| Performance Benchmarking | Comparison with Standard Clinical Systems [12] | Establish comparative advantage over existing clinical practices |

Taxonomy of Common Metric Pitfalls

Figure 2: Taxonomy of Common Metric Pitfalls in Biomedical ML

The translation of machine learning models from research environments to clinical practice hinges on addressing the validation challenges documented in this analysis. The biomedical research community must prioritize external validation across diverse populations and clinical settings, standardized reporting methodologies, and comprehensive assessment of clinical utility [12]. By adopting rigorous validation frameworks and transparent reporting standards, researchers can ensure that machine learning models deliver on their promise to enhance biomedical decision-making while mitigating the risks associated with premature clinical implementation. The development of clinically useful machine learning algorithms requires not only technical excellence but also methodological rigor throughout the validation process, ultimately building trust in these tools among healthcare professionals and patients alike.

In the realm of machine learning (ML), the ultimate test of a model's utility is not its performance on historical data but its ability to make accurate predictions on new, unseen data. This capability is known as generalization [15]. Two of the most significant obstacles to achieving this are overfitting and its counterpart, underfitting, which are governed by a fundamental principle known as the bias-variance tradeoff [16] [17]. For researchers and scientists, particularly in high-stakes fields like drug development, understanding and managing this tradeoff is not merely a theoretical exercise but a practical necessity for validating predictive models and ensuring reliable outcomes. This guide explores these core principles and objectively compares the performance of different machine learning approaches in managing this tradeoff, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Core Conceptual Framework

Defining Bias, Variance, and Overfitting

The performance of a machine learning model can be broken down into three key concepts:

- Bias: Bias is the error that results from overly simplistic assumptions made by a model. A high-bias model fails to capture the underlying patterns in the data, leading to consistent inaccuracies. This phenomenon is also known as underfitting [16] [17] [18].

- Variance: Variance is the error that results from a model's excessive sensitivity to small fluctuations in the training dataset. A high-variance model learns the noise in the training data as if it were a true signal, rather than the intended underlying relationship. This leads to overfitting [16] [19] [17].

- Overfitting: An overfit model performs exceptionally well on its training data but fails to generalize its predictions to new, unseen data [20] [21] [15]. It has essentially "memorized" the training set instead of "learning" from it.

The Mathematical Tradeoff

The bias-variance tradeoff is a formal decomposition of a model's prediction error. For a given data point, the expected prediction error can be expressed as the sum of three distinct components [17]: Total Error = Bias² + Variance + Irreducible Error The irreducible error is the inherent noise in the data itself, which cannot be reduced by any model. The critical insight is that as model complexity increases, bias decreases but variance increases, and vice-versa. This creates a tradeoff where minimizing one error type typically exacerbates the other [16] [17] [18]. The goal is to find a model complexity that minimizes the sum of these errors.

Visualizing the Tradeoff and Model Performance

The relationship between model complexity, error, and the concepts of underfitting and overfitting can be visualized as a U-shaped curve. The following diagram illustrates this fundamental relationship and the "Goldilocks Zone" of optimal model performance.

Experimental Validation: A Case Study in Contamination Classification

Theoretical principles require empirical validation. A 2025 study provides a robust experimental framework for evaluating the bias-variance tradeoff in a real-world industrial application: classifying contamination levels of high-voltage insulators (HVIs) using leakage current data [22].

Experimental Objective and Methodology

- Objective: To develop and validate machine learning models for automatically classifying HVI contamination into three levels (Low, Moderate, High) based on leakage current signals, thereby enabling predictive maintenance [22].

- Data Generation: A meticulous dataset was developed under controlled laboratory conditions. Porcelain insulators were artificially polluted to represent the three contamination classes. Leakage current was measured while critical environmental parameters, such as temperature and humidity, were varied to reflect real-world scenarios [22].

- Feature Engineering: The raw leakage current data was preprocessed, and critical features were extracted from multiple domains: time, frequency, and time-frequency. This step is crucial for providing the model with informative inputs and managing complexity [22].

- Models and Training: Four distinct ML models, encompassing decision trees and neural networks, were trained and evaluated. Bayesian optimization was used to tune the hyperparameters of each model, a process that directly addresses the bias-variance tradeoff by systematically searching for the complexity that minimizes validation error [22].

Comparative Model Performance

The study yielded quantitative results that clearly demonstrate the performance tradeoffs between different types of algorithms. The table below summarizes the key experimental findings.

Table 1: Experimental Performance of ML Models for Contamination Classification

| Model Category | Example Algorithms | Reported Accuracy | Training/Optimization Time | Implied Bias-Variance Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Tree-Based | Random Forest, XGBoost | >98% [22] | Significantly Faster [22] | Well-balanced (ensembling reduces variance) |

| Neural Networks | Deep Neural Networks | >98% [22] | Slower [22] | Potential for high variance if not regulated |

Analysis of Experimental Outcomes

The results indicate that both model categories can achieve high accuracy (>98%) on a well-constructed, experimentally validated dataset [22]. However, the significant difference in training and optimization time is a critical practical consideration. Decision tree-based models (like Random Forest) achieved this high performance much faster. This efficiency is largely due to the effectiveness of ensemble methods, which combine multiple simple models (high bias, low variance) to create a robust aggregate model that reduces overall variance without a proportional increase in bias [16] [22]. Neural networks, while equally accurate, required more time, suggesting greater computational complexity in finding the optimal parameters to avoid overfitting.

A Researcher's Guide to Diagnosis and Mitigation

Diagnostic Protocols

Accurately diagnosing whether a model suffers from high bias or high variance is the first step toward remediation.

- Learning Curves: Plot the model's performance (e.g., loss or accuracy) on both the training and validation sets against the number of training iterations or the size of the training data [16] [15].

- Cross-Validation: A cornerstone of robust model validation, k-fold cross-validation involves partitioning the training data into 'k' subsets. The model is trained k times, each time using a different fold as the validation set and the remaining k-1 folds as the training set. This provides a more reliable estimate of model performance and generalization error than a single train-test split [20].

Mitigation Strategies and Experimental Reagents

To address the issues of bias and variance, researchers can employ a suite of techniques. The following table functions as a "Scientist's Toolkit," detailing key methodological solutions.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Managing Bias and Variance

| Reagent Solution | Function | Primary Target | Experimental Protocol Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Engineering | Creates more informative input variables from raw data to help the model capture relevant patterns [16] [22]. | Reduces Bias | Involves domain expertise to extract features (e.g., time-frequency features from leakage current) [22]. |

| Model Complexity Increase | Switching to more sophisticated algorithms (e.g., from linear to polynomial models) to capture complex relationships [16] [21]. | Reduces Bias | Must be paired with validation to avoid triggering overfitting. |

| Regularization (L1/L2) | Adds a penalty term to the model's loss function to discourage over-reliance on any single feature, effectively simplifying the model [16] [20] [23]. | Reduces Variance | L1 (Lasso) can drive feature coefficients to zero, aiding feature selection. L2 (Ridge) shrinks coefficients uniformly [23]. |

| Ensemble Methods (e.g., Random Forest) | Combines predictions from multiple, slightly different models to average out their errors [16] [20]. | Reduces Variance | Bagging (e.g., Random Forest) is highly effective at reducing variance by averaging multiple high-variance models [16]. |

| Bayesian Optimization | A state-of-the-art protocol for automatically tuning model hyperparameters to find the optimal complexity [22]. | Balances Bias & Variance | More efficient than grid/random search for finding hyperparameters that minimize validation error [22]. |

| Data Augmentation | Artificially expands the training set by creating modified versions of existing data, teaching the model to be invariant to irrelevant variations [20]. | Reduces Variance | Common in image data (e.g., flipping, rotation) but applicable to other domains through noise injection or interpolation. |

The following workflow diagram maps these diagnostic symptoms to the appropriate mitigation strategies, providing a logical pathway for researchers to optimize their models.

The bias-variance tradeoff is an inescapable principle in machine learning that dictates a model's ability to generalize. Through a structured approach involving clear diagnosis via learning curves and cross-validation, and the targeted application of mitigation strategies like regularization and ensemble methods, researchers can systematically navigate this tradeoff. The experimental case study on contamination classification demonstrates that while multiple model types can achieve high accuracy, their paths to balancing bias and variance differ significantly in terms of computational cost and implementation complexity. For the scientific community, particularly in critical fields like drug development, mastering this balance is not optional—it is fundamental to building predictive models that are not only powerful on paper but also reliable and actionable in the real world.

In the rigorous fields of machine learning (ML) and drug development, a significant paradox exists: artificial intelligence models frequently achieve superhuman performance on standardized benchmarks yet fail to deliver comparable results in real-world experimental settings. This gap between controlled testing and practical application poses a particular challenge for research scientists and pharmaceutical professionals who rely on accurate predictions to guide expensive and time-consuming experimental workflows. The high failure rate in drug development—exceeding 96%—underscores the critical nature of this discrepancy, with lack of efficacy in the intended disease indication representing a major cause of clinical phase failure [24].

Benchmarks have long served as the gold standard for comparing AI capabilities, driving healthy competition and measurable progress in the field. However, their static nature, simplified conditions, and failure to account for real-world complexities can lead to misleading conclusions about a model's true utility in scientific discovery [25]. This article examines the fundamental disconnects between benchmark performance and experimental reality, provides a structured framework for more robust validation, and explores practical implications for research professionals navigating the promise and pitfalls of AI-powered discovery.

Evidence of the Disconnect: Case Studies Across Domains

The Performance Gap in Software Engineering

A striking example of the benchmark-reality divergence comes from a 2025 randomized controlled trial (RCT) examining how AI tools affect the productivity of experienced open-source developers. Contrary to both developer expectations and benchmark predictions, the study found that developers allowed to use AI tools took 19% longer to complete issues than those working without AI assistance [26]. This slowdown occurred despite developers' strong belief that AI was speeding up their work—they expected a 24% speedup and, even after experiencing the slowdown, still believed AI had accelerated their work by 20% [26].

Table 1: Software Development RCT - Expected vs. Actual Results

| Metric | Developer Expectation | Reported Belief After Task | Actual Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Task Completion Time | 24% faster with AI | 20% faster with AI | 19% slower with AI |

This controlled experiment highlights how benchmark results and anecdotal reports can dramatically overestimate real-world capabilities. The researchers identified five key factors contributing to the slowdown, including the time spent reviewing, editing, and debugging AI-generated code that often failed to meet the stringent quality requirements of large, established codebases [26].

Contrasting Evidence from Materials Science

In contrast to the software development study, ML applications in materials science demonstrate where benchmark performance can successfully translate to experimental validation. Research published in Nature Communications detailed a machine learning-assisted approach for predicting high-responsivity extreme ultraviolet (EUV) detector materials [27]. Using an Extremely Randomized Trees (ETR) algorithm trained on a dataset of 1927 samples with 23 material features, researchers achieved remarkable predictive accuracy with an R² value of 0.99995 and RMSE of 0.27 on unseen test data [27].

More importantly, this ML-driven approach led to successful experimental validation. The top-predicted material, α-MoO₃, demonstrated responsivities of 20-60 A/W when fabricated and tested, exceeding conventional silicon photodiodes by approximately 225 times in EUV sensing applications [27]. Monte Carlo simulations further validated these results, revealing double electron generation rates (~2×10⁶ electrons per million EUV photons) compared to silicon [27].

Reconciling the Contradictory Evidence

The conflicting outcomes between different domains highlight that the benchmark-reality gap is not universal but highly context-dependent. The following table synthesizes key differences that may explain these divergent outcomes:

Table 2: Reconciling Contradictory Evidence Across Domains

| Factor | Software Development RCT [26] | Materials Science Discovery [27] |

|---|---|---|

| Task Definition | Complex PRs with implicit requirements (style, testing, documentation) | Well-defined prediction of physical properties (responsivity) |

| Success Criteria | Human satisfaction (will pass code review) | Algorithmic scoring (experimental responsivity measurement) |

| Data Context | Large, established codebases requiring deep context | Physical properties with clear feature-property relationships |

| AI Implementation | Interactive tools (Cursor Pro with Claude) | Predictive modeling (Extra Trees Regressor) |

| Output Adjustment | Significant human review and editing required | Direct experimental validation of predictions |

Methodological Differences: Why Benchmarks Mislead

Fundamental Limitations of Benchmark Design

Traditional benchmarks suffer from several structural limitations that reduce their real-world predictive value:

Static Datasets: Benchmarks typically utilize fixed datasets that cannot capture the dynamic, evolving nature of real scientific challenges [25]. This creates a closed-world assumption that fails when models encounter novel data distributions in production environments.

Simplified Task Scope: Benchmark tasks are often artificially constrained to isolate specific capabilities, sacrificing the multidimensional complexity that characterizes actual research problems [26] [25]. For example, coding benchmarks may focus on algorithmic solutions without requiring documentation, testing, or integration into larger systems.

Overfitting Incentives: The competitive nature of benchmark leaderboards encourages optimization for specific metrics rather than generalizable capability, leading to models that learn patterns unique to the benchmark dataset rather than underlying principles [25].

The Experimental Superiority of Randomized Controlled Trials

Whereas benchmarks test AI capabilities in isolation, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluate how AI tools affect human performance in realistic scenarios. The software development study discussed earlier exemplifies this rigorous approach [26]:

This methodological rigor explains why RCT results often contradict benchmark findings—they measure different phenomena in fundamentally different ways.

A Framework for Robust Validation Beyond Benchmarks

Multidimensional Evaluation Strategy

To bridge the benchmark-reality gap, researchers should adopt a comprehensive validation strategy that incorporates multiple evidence sources:

Human-in-the-Loop Evaluation: Incorporate expert human assessment to evaluate qualities that automated metrics miss, such as practical utility, appropriateness for context, and alignment with scientific intuition [25].

Real-World Deployment Testing: Test AI systems in environments that closely simulate actual research conditions, including the noise, uncertainty, and unexpected variables characteristic of laboratory settings [25].

Robustness and Stress Testing: Subject models to adversarial conditions, distribution shifts, and edge cases to assess performance boundaries and failure modes [25].

Domain-Specific Validation: Develop customized tests that reflect the particular requirements and constraints of specific scientific domains, such as using case studies designed by subject matter experts [25].

Standardized Experimental Protocol for AI Validation

For drug development professionals evaluating AI tools, the following workflow provides a structured approach to validation:

This protocol emphasizes the critical importance of progressing from benchmark performance to controlled experimental validation, particularly for high-stakes applications like drug development.

Research Reagent Solutions for AI Validation

Table 3: Essential Methodological Components for Robust AI Validation

| Methodological Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | Isolate AI effect from confounding variables by random assignment to conditions | Assign researchers to AI-assisted vs. control groups for identical tasks [26] |

| Cross-Spectral Prediction Frameworks | Leverage existing data in related domains to predict performance in target domain | Use visible/UV photoresponse data to predict EUV material performance [27] |

| Machine Learning-Based Randomization Validation | Detect potential bias in experimental assignment using ML pattern recognition | Apply supervised ML models to verify randomization in study designs [28] |

| Multi-Metric Performance Assessment | Evaluate models across diverse metrics beyond single-score accuracy | Measure precision, recall, F1 score, and domain-specific metrics [29] |

| Real-World Deployment Environments | Test models under actual use conditions with all inherent complexities | Deploy AI tools in active research projects with performance tracking [25] |

Implications for Drug Development Professionals

Addressing the Drug Development Failure Crisis

The pharmaceutical industry faces particularly severe consequences from the benchmark-reality gap. With over 96% failure rates in drug development and lack of efficacy representing the major cause of late-stage failure, improved prediction of therapeutic potential is urgently needed [24]. Statistical analysis suggests that the false discovery rate (FDR) in preclinical research may be as high as 92.6%, largely because the proportion of true causal protein-disease relationships is estimated at just 0.5% (γ = 0.005) [24].

The FDR in preclinical research can be mathematically represented as:

$$FDR=\frac{\alpha (1-\gamma )}{(1-\beta )\,\gamma +\alpha \,(1-\gamma )}$$

Where:

- $\gamma$ = proportion of true target-disease relationships (≈0.005)

- $\beta$ = false-negative rate

- $1-\beta$ = power to detect real effects

- $\alpha$ = false-positive rate (typically 0.05) [24]

This high FDR means that seemingly promising target-disease hypotheses progress from preclinical to clinical testing despite having no causal relationship, resulting in expensive late-stage failures.

Genomic Validation as a Solution

Human genomics offers a promising alternative to traditional preclinical studies for drug target identification. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) overcome many design flaws inherent in standard preclinical testing by:

- Experimenting in the correct organism (humans)

- Employing exceptionally low false discovery rates

- Systematically interrogating every potential drug target concurrently

- Leveraging genetic variation that mimics randomized controlled trial design [24]

This approach has demonstrated predictive value, with genetic studies accurately predicting success or failure in randomized controlled trials and helping to separate mechanism-based from off-target drug actions [24].

The consistent discrepancy between benchmark performance and experimental outcomes underscores a fundamental limitation in current AI evaluation methodologies. For research scientists and drug development professionals, relying solely on benchmark results represents an unacceptable risk given the high costs of failed experiments and delayed discoveries.

The path forward requires a fundamental shift in validation practices—from benchmark-centric to reality-aware evaluation. This involves supplementing traditional benchmarks with controlled experiments, real-world deployment testing, and domain-specific validation protocols that reflect the actual conditions and requirements of scientific research. By adopting these more rigorous approaches, the research community can better harness the genuine potential of AI tools while avoiding the costly dead ends that arise from overreliance on misleading benchmark scores.

As AI capabilities continue to evolve, so too must our methods for evaluating them. The ultimate benchmark for any AI system in scientific research is not its performance on standardized tests, but its ability to deliver reliable, reproducible, and meaningful advances in human knowledge and therapeutic outcomes.

In the rapidly expanding universe of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML), the research community faces a significant hurdle: ensuring the reproducibility of groundbreaking research. This growth has been shadowed by a reproducibility crisis, where researchers often struggle to recreate results from studies, be it the work of others or even their own. This challenge not only raises questions about the reliability of research findings but also points to a broader issue within the scientific process in AI/ML. Instances where attempts to re-execute experiments led to a wide array of results—even under identical conditions—illustrate the unpredictable nature of current research practices. As AI and ML continue to promise revolutionary changes across industries, particularly in high-stakes fields like drug development, the imperative to ensure that research is not just innovative but also reproducible has never been clearer [30].

Defining the Validation Framework

Core Terminology

Addressing the reproducibility crisis begins with clarifying the often-confused terminology around research validation. At Ready Tensor, the hierarchy of validation studies is defined through precise terminology that establishes different levels of scientific scrutiny [30]:

- Repeatability: Focuses on the consistency of research outcomes when the original team re-executes their experiment under unchanged conditions. It underscores the reliability of the findings within the same operational context and serves as a fundamental check for any study's internal consistency.

- Reproducibility: Achieved when independent researchers validate the original experiment's findings by employing the documented experimental setup. This validation can occur through two pathways: dependent reproducibility (using the original code and data) or independent reproducibility (reimplementing the experiment without original artifacts).

- Direct Replicability: Involves an independent team's effort to validate the original study's results by intentionally altering the experiment's implementation, yet keeping the hypothesis and experimental design consistent. This variation can include changes in datasets, methodologies, or analytical approaches.

- Conceptual Replicability: Extends the validation process by testing the same hypothesis through an entirely new experimental approach. This represents the highest level of scrutiny, assessing whether findings hold across significantly different methodological frameworks.

The Validation Hierarchy

The progression from repeatability to conceptual replicability forms a validation hierarchy that significantly impacts scientific rigor and reliability. This framework not only enhances trust in the findings but also tests their robustness and applicability under varied conditions. Each level addresses distinct aspects of validation [30]:

- Repeatability ensures the initial integrity of findings, confirming that results are consistent and not random occurrences.

- Dependent and independent reproducibility elevate this scrutiny. Dependent reproducibility confirms the accuracy of results using the same materials, while independent reproducibility tests if findings can be replicated with different tools, assessing the experiment's description for clarity and completeness.

- Direct and conceptual replicability represent the hierarchy's peak, offering the highest scrutiny levels. Direct replicability examines the stability of findings across methodologies, whereas conceptual replicability assesses the generalizability of conclusions in new contexts.

This structured approach to validation is particularly crucial in drug development, where the translational pathway from computational prediction to clinical application demands exceptional rigor at every stage.

Industry Benchmarking: Quantitative Performance Comparisons

MLPerf Inference v5.1 Benchmark Results

The MLPerf Inference benchmark suite is designed to measure how quickly AI systems can run models across various workloads. As an open-source and peer-reviewed suite, it performs system performance benchmarking in an architecture-neutral, representative, and reproducible manner, creating a level playing field for competition that drives innovation, performance, and energy efficiency for the entire industry. The v5.1 suite introduces three new benchmarks that further challenge AI systems to perform at their peak against modern workloads, including DeepSeek-R1 with reasoning, and interactive scenarios with tighter latency requirements for some LLM-based tests [31].

Table: MLPerf Inference v5.1 Benchmark Overview (New Tests)

| Benchmark | Model Type | Key Applications | Dataset Used | System Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSeek-R1 | Reasoning Model | Mathematics, QA, Code Generation | 5 specialized datasets | Datacenter & Edge |

| Llama 3.1 8B | LLM (8B parameters) | Text Summarization | CNN-DailyMail | Datacenter & Edge |

| Whisper Large V3 | Speech Recognition | Transcription, Translation | Modified Librispeech | Datacenter & Edge |

The September 2025 MLPerf Inference v5.1 results revealed substantial performance gains over prior rounds, with the best performing systems improving by as much as 50% over the best system in the 5.0 release just six months ago in some scenarios. The benchmark received submissions from 27 organizations, including systems using five newly-available processors: AMD Instinct MI355X, Intel Arc Pro B60 48GB Turbo, NVIDIA GB300, NVIDIA RTX 4000 Ada-PCIe-20GB, and NVIDIA RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell Server Edition [31].

Geekbench ML AI Performance Results

Complementing the MLPerf benchmarks, Geekbench ML provides valuable performance metrics across diverse hardware platforms, from mobile devices to high-performance computing systems. The results from August 2024 reveal interesting performance patterns across different precision formats and hardware architectures [32].

Table: Geekbench ML AI Performance Results (August 2024)

| Device | Processor | Framework | Single Precision | Half Precision | Quantized |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPhone 16 Pro Max | Apple A18 Pro | Core ML Neural Engine | 4691 | 33180 | 44683 |

| iPhone 15 Pro Max | Apple A17 Pro | Core ML Neural Engine | 3868 | 26517 | 36475 |

| iPad Pro 11-inch (M4) | Apple M4 | Core ML CPU | 4895 | 8006 | 6365 |

| ASUS System | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5080 | ONNX DirectML | 36563 | 60834 | 27841 |

| ASUS System | AMD Ryzen 7 9800X3D | OpenVINO CPU | 13152 | 13100 | 30426 |

| Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra | Qualcomm Snapdragon 8 Gen 3 | TensorFlow Lite CPU | 2517 | 2531 | 3680 |

The data reveals several noteworthy trends for research applications. First, the Apple A18 Pro's Neural Engine demonstrates exceptional performance in half-precision and quantized operations, which are crucial for efficient deployment of models on edge devices. Second, NVIDIA's RTX 5080 shows dominant performance in single and half-precision computations, making it well-suited for training and inference in research environments. Third, the performance differentials across precision formats highlight the importance of selecting appropriate numerical formats for specific research applications, with quantized models often providing the best performance on mobile and edge-focused hardware [32].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Benchmarking Methodology

The MLPerf Inference working group has established rigorous methodologies for benchmarking that ensure fair and representative performance measurements. For the newly introduced DeepSeek-R1 benchmark, which is the first "reasoning model" in the suite, the workload incorporates prompts from five datasets covering mathematics problem-solving, general question answering, and code generation. Reasoning models represent an emerging and important area for AI models, with their own unique pattern of processing that involves a multi-step process to break down problems into smaller pieces to produce higher quality responses [31].

For the Llama 3.1 8B benchmark, which replaces the older GPT-J model while retaining the same dataset, the test uses the CNN-DailyMail dataset among the most popular publicly available for text summarization tasks. A significant advancement in this benchmark is the use of a large context length of 128,000 tokens, whereas GPT-J only used 2048, better reflecting the current state of the art in language models. The Whisper Large V3 benchmark employs a modified version of the Librispeech audio dataset and stresses system aspects such as memory bandwidth, latency, and throughput through its combination of language modeling with additional stages like acoustic feature extraction and segmentation [31].

Implementation Workflow

Implementing a rigorous validation protocol for ML-driven research requires meticulous attention to the entire experimental pipeline, from data preparation to performance analysis. The following workflow visualization captures the critical stages in establishing a reproducible benchmarking process:

The experimental workflow emphasizes several critical validation checkpoints:

Data Splitting Protocols: Proper partitioning of datasets into training, validation, and test sets is fundamental to preventing data leakage and ensuring realistic performance assessment. For the Llama 3.1 8B summarization benchmark, this involves careful curation of the CNN-DailyMail dataset to maintain temporal boundaries between splits [31] [33].

Framework-Specific Optimization: Each hardware platform requires specialized framework configuration to achieve optimal performance. The substantial differences observed between Core ML Neural Engine, ONNX DirectML, and TensorFlow Lite implementations highlight the importance of platform-specific optimizations [32].

Precision Format Selection: Researchers must carefully select appropriate numerical precision formats (single precision, half precision, quantized) based on their specific accuracy and performance requirements, as demonstrated by the significant performance variations across precision formats in the Geekbench results [32].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

For researchers implementing validation protocols in ML-driven research, particularly in computational drug development, specific computational tools and frameworks serve as essential "research reagents" with clearly defined functions in the experimental workflow.

Table: Essential Computational Research Reagents for ML Validation

| Tool/Framework | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core ML | Model deployment & optimization | Apple ecosystem inference | Hardware acceleration, Neural Engine support |

| ONNX DirectML | Cross-platform model execution | Windows ecosystem, diverse hardware | DirectX integration, multi-vendor support |

| TensorFlow Lite | Mobile & edge deployment | Android ecosystem, embedded systems | NNAPI delegation, quantization support |

| OpenVINO | CPU-focused optimization | Intel hardware ecosystems | Model optimization, heterogeneous execution |

| MLPerf Benchmarking Suite | Performance validation | Cross-platform comparison | Standardized workloads, reproducible metrics |

| Docker Containers | Environment reproducibility | SWE-Bench and other benchmarks | Consistent execution environment [34] |

These computational reagents form the foundation of reproducible ML research workflows, enabling fair comparisons across different hardware and software platforms. The Docker containers released for SWE-Bench, for instance, provide pre-configured environments that make benchmark execution consistent and reproducible across different research setups [34].

The establishment of a robust validation mindset in ML-driven research requires concerted effort across multiple dimensions of the research lifecycle. From adopting precise terminology distinguishing repeatability, reproducibility, and replicability, to implementing standardized benchmarking protocols like MLPerf Inference and Geekbench ML, the path toward more rigorous and trustworthy ML research is clear [30] [32] [31]. As the field continues to evolve at a breathtaking pace, with new processors, models, and benchmarking approaches emerging regularly, the commitment to methodological rigor and experimental transparency becomes increasingly critical—particularly in high-stakes applications like drug development where research predictions must eventually translate to real-world outcomes.

Validation in Action: Methodologies for Testing ML Predictions Against Experimental Data

In the rigorous fields of scientific research and drug development, the ability to trust a machine learning model's predictions is paramount. A model's performance on known data is a poor indicator of its real-world utility if it cannot generalize to new, unseen data—a flaw known as overfitting. Consequently, robust validation frameworks are not merely a technical step but the foundation of credible, reproducible computational science. These frameworks provide the statistical evidence needed to ensure that a model predicting molecular bioactivity, patient outcomes, or clinical trial results will perform reliably in practice [35].

The choice of validation strategy directly impacts the reliability of model evaluation and comparison. Within biomedical machine learning, concerns about reproducibility are prominent, and the improper application of validation techniques can contribute to a "reproducibility crisis" [36]. The core challenge is to accurately estimate a model's performance on independent data sets, flagging issues like overfitting or selection bias that can lead to overly optimistic results and failed real-world applications [37]. This guide objectively compares the two most foundational validation approaches—the hold-out method and k-fold cross-validation—providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols necessary to make informed decisions for their projects.

Core Concepts and Definitions

The Hold-Out Method

The hold-out method is the simplest approach to validation. It involves splitting the available dataset once into two mutually exclusive subsets: a training set and a test set [37] [38]. A common split is to use 80% of the data for training the model and the remaining 20% for testing its performance [39]. The model is trained once on the training set and its performance is evaluated once on the held-out test set, providing an estimate of how it might perform on unseen data.

The k-Fold Cross-Validation Method

k-fold cross-validation is a more robust resampling technique. The original sample is randomly partitioned into k equal-sized subsamples, or "folds" [37]. Of these k folds, a single fold is retained as the validation data for testing the model, and the remaining k-1 folds are used as training data. The process is then repeated k times, with each of the k folds used exactly once as the validation data. The k results from these iterations are then averaged to produce a single, more reliable estimation of the model's predictive performance [40] [37]. A common and recommended choice for k is 10, as it provides a good balance between bias and variance [40].

Comparative Analysis: Hold-Out vs. k-Fold Cross-Validation

The choice between hold-out and k-fold cross-validation involves a direct trade-off between computational efficiency and the reliability of the performance estimate. The following table summarizes the key differences based on established practices and reported findings.

Table 1: A direct comparison of the hold-out and k-fold cross-validation methods.

| Feature | Hold-Out Method | k-Fold Cross-Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Split | Single split into training and test sets [39] | Dataset divided into k folds; each fold serves once as a test set [40] |

| Training & Testing | Model is trained once and tested once [40] | Model is trained and tested k times [40] |

| Computational Cost | Lower; only one training cycle [39] [38] | Higher; requires k training cycles [39] [38] |

| Performance Estimate Variance | Higher variance; dependent on a single data split [39] [38] | Lower variance; averaged over k splits, providing a more stable estimate [39] [38] |

| Bias | Can have higher bias if the single split is not representative [40] | Generally lower bias; uses more data for training in each iteration [40] |

| Best Use Case | Very large datasets, time constraints, or initial model prototyping [39] [40] | Small to medium-sized datasets where an accurate performance estimate is critical [39] [40] |

The primary advantage of k-fold cross-validation is its ability to use the available data more effectively, reducing the risk of an optimistic or pessimistic performance estimate based on an unlucky single split. This is crucial in domains like drug discovery, where datasets are often limited. As one analysis noted, cross-validation provides an out-of-sample estimate of model fit, which is essential for understanding how the model will generalize, whereas a simple training set evaluation is an in-sample estimate that is often optimistically biased [37].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To ensure reproducibility and proper implementation, below are detailed methodological protocols for both validation strategies.

Protocol for the Hold-Out Validation Method

This protocol is designed for simplicity and speed, suitable for large datasets or initial model screening.

- Dataset Preparation: Begin with a cleaned and pre-processed dataset. If dealing with a classification problem and an imbalanced dataset, consider using stratified splitting to maintain class proportions in the train and test sets [35].

- Random Splitting: Randomly shuffle the dataset and split it into two parts: a training set (typically 70-80% of the data) and a test set (the remaining 20-30%). To ensure reproducibility, set a random seed before splitting [35].

- Model Training: Train the machine learning model (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) using only the training set.

- Model Testing & Evaluation: Use the trained model to make predictions on the held-out test set. Calculate the chosen performance metric(s) (e.g., Accuracy, ROC-AUC, Precision-Recall AUC).

- Result Reporting: The performance on the test set serves as the final estimate of the model's generalization error.

Protocol for the k-Fold Cross-Validation Method

This protocol provides a more thorough evaluation of model performance and is recommended for final model selection and tuning.

- Determine k and Prepare Folds: Choose the number of folds k (e.g., 5 or 10). Randomly shuffle the dataset and split it into k folds of approximately equal size. For classification, use stratified k-fold to ensure each fold has the same class distribution as the full dataset [40] [35].

- Iterative Training and Validation: For each unique fold

i(whereiranges from 1 to k):- Use fold

ias the validation set. - Use the remaining k-1 folds as the training set.

- Train the model on the training set.

- Validate the model on the validation set and store the performance metric for that fold.

- Use fold

- Aggregate Results: Once all k iterations are complete, compute the average of the k performance metrics. This average is the final cross-validation performance score. The standard deviation of the k scores can also be reported to indicate the variability of the estimate.

- Final Model Training (Optional): After identifying the best model and parameters via cross-validation, it is common practice to retrain the model on the entire dataset to produce a final model for deployment [38].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow for the k-fold cross-validation process.

Supporting Experimental Data from Biomedical Research

The theoretical trade-offs between hold-out and k-fold cross-validation are borne out in practical, high-stakes research settings. The comparative performance of these methods is not just academic but has direct implications for the conclusions drawn in scientific studies.

Case Study: Validation in Genetic Association Studies

Research into improving machine learning reproducibility in genetic association studies highlights a key limitation of traditional validation when data is highly structured or imbalanced. A study focused on detecting epistasis (non-additive genetic interactions) found that a standard hold-out or k-fold validation, which randomly allocates individuals to training and testing sets, can lead to poor consistency between splits. This inconsistency arises from an imbalance in the interaction genotypes within the data. To address this, researchers proposed Proportional Instance Cross Validation (PICV), a method that preserves the original distribution of an independent variable (e.g., a specific SNP-SNP interaction) when splitting the data. The study concluded that PICV significantly improved sensitivity and positive predictive value compared to traditional validation, demonstrating how a default validation choice can be suboptimal for specialized biomedical data structures [41].

Case Study: Comparing Models for Bioactivity Prediction

A large-scale reanalysis of machine learning models for bioactivity prediction underscores the variability inherent in performance evaluation. The study reexamined a benchmark comparison that concluded deep learning methods significantly outperformed traditional methods like Support Vector Machines (SVMs). The reanalysis found that this conclusion was highly dependent on the specific assays (experimental tests) examined. For some assays, performance was highly variable with large confidence intervals, while for others, results were stable and showed SVMs to be competitive with or even outperform deep learning. This variability calls for robust validation methods like k-fold cross-validation, which can provide a more stable and reliable estimate of model performance across different data scenarios. Relying on a single train-test split (hold-out) in such a heterogeneous context could easily lead to misleading conclusions about a model's true efficacy [42].

Table 2: Algorithm accuracy rates reported in a study using World Happiness Index data for clustering-based classification, demonstrating performance variation across models.

| Machine Learning Algorithm | Reported Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | 86.2% |

| Decision Tree | 86.2% |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 86.2% |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | 86.2% |

| Random Forest | Data Not Specified |

| XGBoost | 79.3% |

Source: Adapted from a 2025 study comparing ML algorithms on World Happiness Index data [43]. Note that these results are context-specific and serve as an example of performance reporting.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing robust validation frameworks requires both conceptual understanding and practical tools. The following table details key computational "reagents" and their functions in the validation process.

Table 3: Key computational tools and concepts for building robust validation frameworks.

| Tool / Concept | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Stratified k-Fold | A variant of k-fold that ensures each fold has the same proportion of class labels as the full dataset. Critical for validating models on imbalanced datasets (e.g., rare disease prediction) [40] [35]. |

| Random Seed | An integer used to initialize a pseudo-random number generator. Setting a fixed random seed ensures that the data splitting process (for both hold-out and k-fold) is reproducible, which is a cornerstone of scientific experimentation [35]. |

| Performance Metrics (e.g., ROC-AUC, PR-AUC) | Quantitative measures used to evaluate model performance. Using multiple metrics (e.g., Area Under the ROC Curve combined with Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve) provides a more comprehensive view, especially for imbalanced data common in biomedical contexts [42]. |

| Hyperparameter Tuning (Grid/Random Search) | The process of searching for the optimal model parameters. Cross-validation is the gold standard for reliably evaluating different hyperparameter combinations during this tuning process to prevent overfitting to the training data [35]. |

Selecting an appropriate validation framework is a critical decision that directly impacts the credibility of machine learning predictions in scientific research. The choice between hold-out and k-fold cross-validation is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of aligning the method with the project's constraints and goals.

Based on the comparative analysis and experimental data, we recommend:

- Use the Hold-Out Method when working with very large datasets, operating under significant time or computational constraints, or during the initial prototyping phase of a model [39] [40]. Its speed and simplicity are its greatest assets in these scenarios.

- Use k-Fold Cross-Validation for small to medium-sized datasets where obtaining a reliable and stable performance estimate is the highest priority. It is the preferred method for final model evaluation, comparison, and hyperparameter tuning as it reduces variance and provides a more robust out-of-sample performance estimate by leveraging the entire dataset [39] [40] [38].

For researchers in drug development and related fields, where data is often limited, expensive to acquire, and imbalanced, the extra computational cost of k-fold cross-validation is a worthwhile investment. It mitigates the risk of building models on a non-representative data split, thereby strengthening the statistical foundation upon which scientific and resource-allocation decisions are made. Ultimately, a rigorously validated model is not just a technical achievement; it is a prerequisite for trustworthy and reproducible science.

In the rigorous field of machine learning (ML), particularly in scientific domains like drug development, the validation of predictive models is paramount. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) such as Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and AUC-ROC provide the essential metrics for this validation, translating model outputs into reliable, actionable insights. Framed within a broader thesis on validating machine learning predictions with experimental results, this guide offers an objective comparison of these core metrics. It details their underlying methodologies and illustrates their application through experimental data, serving as a critical resource for researchers and scientists who require robust, evidence-based model evaluation.

Core Metric Definitions and Comparative Analysis

The following table provides a concise summary of the primary KPIs used to evaluate binary classification models, which are foundational to assessing model performance in experimental machine learning research.

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation & Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy [44] | The proportion of total correct predictions (both positive and negative) out of all predictions made. | Measures overall model correctness. Can be misleading with imbalanced datasets, as it may be skewed by the majority class. |

| Precision [44] | The proportion of correctly predicted positive instances out of all instances predicted as positive. | Answers: "Of all the instances we labeled as positive, how many are actually positive?" Focuses on the reliability of positive predictions. |

| Recall [44] | The proportion of correctly predicted positive instances out of all actual positive instances. | Answers: "Of all the actual positive instances, how many did we successfully find?" Focuses on the model's ability to capture all positives. |

| F1-Score [45] [44] | The harmonic mean of Precision and Recall. | Provides a single metric that balances the trade-off between Precision and Recall. It is especially useful when you need to consider both false positives and false negatives equally. |

| AUC-ROC [45] | The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve, which plots the True Positive Rate (Recall) against the False Positive Rate at various classification thresholds. | Measures the model's overall ability to discriminate between positive and negative classes across all possible thresholds. A higher AUC indicates better class separation. |

Experimental Protocols and Quantitative Comparison

To objectively compare these KPIs, it is essential to apply them within a concrete experimental framework. The following section outlines a real-world experimental protocol and presents quantitative results comparing a novel ML model against an established clinical benchmark.

Detailed Methodology: Predicting Medical Device Failure

A recent multicenter study developed and externally validated a gradient boosting model to predict High-Flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC) failure in patients with acute hypoxic respiratory failure, providing a robust example of ML validation in a high-stakes environment [46].

- Study Design and Population: The research was a retrospective cohort study that enrolled adult inpatients from seven hospitals across four health systems. Patients were excluded if they were intubated before first HFNC use, experienced the primary outcome less than one hour after HFNC initiation, or had missing data required to calculate the comparison benchmark [46].

- Predictive Task: The model was designed to predict a composite primary outcome of intubation or death within the next 24 hours at the time of HFNC initiation [46].

- Model and Benchmark: A gradient boosting machine learning model was trained and compared against the ROX Index, a previously published and clinically established metric for predicting HFNC failure [46].

- Validation: The model was developed on a training cohort and then tested on a separate, external validation cohort to ensure generalizability. The performance of both the ML model and the ROX Index was evaluated using the AUC-ROC at multiple time points (2, 6, 12, and 24 hours) [46].

Quantitative Results and KPI Comparison

The external validation results demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in performance for the ML model over the traditional clinical benchmark [46].

| Model / Metric | AUC-ROC at 24 Hours | Statistical Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|

| Novel ML Model | 0.760 | < 0.001 |

| ROX Index (Benchmark) | 0.696 | - |

This experimental data showcases AUC-ROC as a critical KPI for comparing the discriminatory power of different models on an objective scale. The clear superiority of the ML model's AUC-ROC, validated across multiple time points and a large patient cohort, provides strong evidence for its potential clinical utility [46]. This underscores the importance of using robust, data-driven KPIs to validate new predictive methodologies against existing standards.

Visualization of Metric Relationships and Experimental Workflow

Understanding the logical relationships between metrics and the experimental workflow is crucial for proper validation. The following diagrams, created with DOT language, visualize these concepts.

Diagram 1: KPI Relationship Hierarchy

This diagram shows how core classification metrics are derived from the fundamental counts in a confusion matrix.

Diagram 2: Experimental Validation Workflow

This diagram outlines the end-to-end process for developing and validating a machine learning model, as exemplified in the HFNC study [46].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for ML Validation

Beyond theoretical metrics, the rigorous validation of ML models relies on a suite of methodological "reagents" and tools. The following table details key components used in the featured experiment and the broader field [46].

| Tool / Solution | Function in Validation |

|---|---|