Gas Adsorption Techniques for Catalyst Characterization: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of gas adsorption techniques, a cornerstone of catalyst characterization.

Gas Adsorption Techniques for Catalyst Characterization: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of gas adsorption techniques, a cornerstone of catalyst characterization. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of physisorption and chemisorption, details standard methodologies and data interpretation, offers troubleshooting and optimization strategies for real-world challenges, and provides a framework for validating and comparing results with other analytical techniques. The goal is to equip practitioners with the knowledge to accurately determine critical catalyst properties such as surface area, pore size distribution, metal dispersion, and active site density, thereby enhancing catalyst development and optimization for applications ranging from chemical synthesis to biomedical processes.

Understanding the Fundamentals: How Gas Adsorption Reveals Catalyst Properties

Fundamental Definitions and Distinctions

Adsorption is a process in which atoms, ions, or molecules from a substance (adsorbate) adhere to the surface of a solid or liquid (adsorbent) [1]. This is classified as an exothermic process because energy is released when the adsorbed substance sticks to the surface of the adsorbent material [1]. The rate of adsorption depends mainly on the surface area and temperature, with lower temperatures generally promoting the process [1].

In contrast, absorption occurs when molecules pass into and are assimilated throughout the bulk of a material, effectively forming a solution [1]. The particles diffuse or dissolve into the absorbent material, and once dissolved, cannot be easily separated [1]. A common example is a paper towel absorbing water, where the liquid evenly permeates the entire material [1].

The surface of any material is composed of atoms and bonds that are exposed to the surrounding environment. For instance, the surface of a piece of glass contains silicon and oxygen atoms that can interact with surrounding molecules through intermolecular interactions, allowing them to 'stick' or adsorb to the surface [2]. Materials with very high surface areas provide extensive surfaces for molecules to adhere to, making them particularly effective as adsorbents [2].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Adsorption vs. Absorption

| Characteristic | Adsorption | Absorption |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Accumulation of molecular species at the surface [1] | Assimilation of particles throughout the bulk of the solid or liquid [1] |

| Mass Transfer | Liquid particles onto solids [1] | Liquid particles into solids [1] |

| Phenomenon | Surface phenomenon [1] | Bulk phenomenon [1] |

| Heat Exchange | Exothermic process [1] | Endothermic process [1] |

| Temperature Effect | Favored by low temperatures [1] | Not significantly affected by temperature [1] |

| Reaction Rate | Increases steadily and reaches equilibrium [1] | Occurs at a uniform rate [1] |

| Concentration | Surface concentration differs from internal concentration [1] | Concentration eventually becomes uniform throughout the material [1] |

Adsorption in Catalyst Characterization

In catalyst characterization, gas adsorption techniques provide critical information about both the catalyst support and the active metal phase [3]. Physical gas adsorption is primarily used to analyze the support properties, while chemical gas adsorption (chemisorption) employs reactive gases (typically hydrogen or carbon monoxide) to probe the active properties of the metal phase in supported metal catalysts [3].

Chemisorption provides quantitative information on the active metal phase, including metal surface area, metal dispersion, and metal crystallite size, enabling researchers to correlate catalyst properties with catalytic performance [3]. This makes chemisorption a powerful characterization tool in catalyst development and optimization.

Standard catalyst characterization techniques such as gas adsorption porosimetry and mercury porosimetry have limitations—they account for some physical heterogeneity of the catalyst surface but completely ignore chemical heterogeneity, and in most cases consider pores to be independent of each other [4]. This results in inaccurate descriptors like BET surface area, BJH pore size distribution, and mercury porosimetry surface area [4].

Experimental Protocols for Catalyst Characterization via Chemical Gas Adsorption

Volumetric Chemisorption Method

The volumetric method for chemical gas adsorption follows a precise experimental workflow:

Protocol Details:

Sample Preparation: The catalyst sample is loaded into the analysis tube of a Quantachrome Autosorb-1C or Autosorb iQ adsorption analyzer [3].

Reduction: The sample is reduced in hydrogen flow to activate the metal surface and remove surface oxides [3].

Evacuation: The system is evacuated to remove physisorbed species and retrieve the active metal surface [3].

Gas Dosing: Known amounts of reactive gas (hydrogen for Pt, Ni, Rh, Ru; carbon monoxide for Pd, Pt) are dosed and subsequently adsorbed at different partial pressures, resulting in a chemisorption isotherm [3].

Dual-Isotherm Measurement: The isotherm measurement is repeated after applying an evacuation step at the analysis temperature to remove weakly adsorbed species (back-sorption or dual-isotherm method) [3].

Data Analysis: The difference between the two isotherms represents the chemically bonded reactive gas, which is used to calculate the active metal surface area [3]. Combined with metal loading information, the metal dispersion and average metal crystallite size can be determined.

Table 2: Key Parameters in Chemisorption Experiments

| Parameter | Application | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen (H₂) | Used for Pt, Ni, Rh, Ru characterization [3] | Determines active metal surface area of these catalysts |

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) | Used for Pd, Pt characterization [3] | Selective chemisorption for these metal surfaces |

| Analysis Temperature | Typically 25-35°C for precise measurements | Affords chemical adsorption rather than physical adsorption |

| Evacuation Step | Between isotherm measurements in dual-isotherm method | Removes weakly adsorbed species for accurate strong chemisorption measurement |

| Metal Dispersion | Calculated from chemisorption data | Percentage of metal atoms on surface relative to total metal atoms |

| Crystallite Size | Derived from chemisorption data | Average size of metal particles on support |

Advanced Characterization Approaches

Novel approaches address the limitations of standard characterization techniques. Integrated nitrogen-water-nitrogen gas adsorption experiments on fresh and coked catalysts can establish the significance of pore coupling by demonstrating advanced adsorption [4]. This method also helps determine the location of coke deposits within catalysts and indicates that water vapor adsorption serves as a good probe to understand the sites responsible for coking [4].

Coadsorption of immiscible liquids (cyclohexane and water) followed by studying the displacement of cyclohexane by water using NMR relaxometry and diffusometry represents another advanced approach [4]. This method accounts for the wettability and chemical heterogeneity of the surface, providing more comprehensive characterization data [4].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Adsorption Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Silica Gels | Moisture adsorption for humidity control [1] | Used in rotors with honeycomb structure coated with silica gel in adsorption dehumidifiers |

| Kaolinite | Si/Al-based mineral adsorbent for heavy metal capture [5] | Shows higher adsorption capacity for Pb and Cd than pure SiO₂ and Al₂O₃ |

| Montmorillonite | Si/Al-based mineral adsorbent [5] | Effective for heavy metal vapor capture in high-temperature applications |

| Hydrogen (H₂) | Reactive gas for chemisorption of Pt, Ni, Rh, Ru [3] | High purity required for accurate measurements |

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) | Reactive gas for chemisorption of Pd, Pt [3] | Toxic gas requiring proper safety protocols |

| Nitrogen (N₂) | Analysis gas for physical adsorption measurements [4] | Used at cryogenic temperatures for surface area analysis |

| Quantachrome Autosorb Systems | Automated gas adsorption analyzers [3] | Enable precise volumetric measurements of gas uptake |

Molecular-Level Adsorption Mechanisms

The adsorption characteristics of Si/Al-based adsorbents can be investigated through combined experimental and theoretical approaches. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations provide an effective method and theoretical basis for revealing chemisorption mechanisms at the molecular level [5].

DFT studies have shown that the numerous Si-O/Al-O bonds in Si/Al-based compounds can combine with heavy metals to form stable compounds, explaining the high chemisorption performance of these materials [5]. For example, research has revealed that the Al surface of kaolinite with dehydroxylation is highly active for lead vapor adsorption, while the Si surface is relatively inert [5].

The interaction pathways and reaction mechanisms of various adsorbate species on adsorbent surfaces can be investigated through analysis of adsorption energy, charge density distribution, charge density difference, and partition density of states [5]. This combined experimental and theoretical approach contributes significantly to understanding adsorption mechanisms in catalytic systems.

This framework for understanding adsorption as a surface phenomenon distinct from bulk absorption provides the foundation for advanced catalyst characterization techniques essential for research and development in catalysis and related fields.

Gas adsorption is a fundamental process in which gas molecules (the adsorbate) adhere to the surface of a solid material (the adsorbent) [6]. For researchers in catalysis and drug development, understanding and quantifying this phenomenon is critical, as a catalyst's performance and a drug's dissolution profile are directly influenced by surface properties [7]. The interaction between the adsorbate and adsorbent occurs primarily through two distinct mechanisms: physisorption (physical adsorption) and chemisorption (chemical adsorption) [6] [8]. While physisorption involves weak, reversible van der Waals forces, chemisorption involves the formation of strong, typically irreversible chemical bonds [6] [8]. The distinction is not merely academic; it dictates the analytical techniques used, the information gleaned about the material, and the ultimate application of the data, whether for designing a more efficient catalyst or optimizing a drug delivery system [9]. This article provides a detailed framework for distinguishing between these processes, with a specific focus on practical protocols for catalyst characterization.

Fundamental Principles and Key Distinctions

Physisorption: Weak Forces for Surface and Pore Analysis

Physisorption is characterized by the weak bonding of gas molecules to a solid surface, primarily through van der Waals forces [6] [7]. These are the same forces responsible for the condensation of gases into liquids, and consequently, the enthalpies involved are comparable to the heat of liquefaction, typically ranging from 5 to 50 kJ/mol [8]. A key characteristic of physisorption is its reversibility; because no chemical bonds are broken or formed, the process can be easily reversed by reducing the pressure or increasing the temperature [6] [8]. Furthermore, physisorption is non-specific, meaning it can occur on any surface, and is favored at low temperatures [8]. As gas pressure increases, the adsorption progresses from a monolayer to multilayers, and in porous materials, pores fill from the smallest to the largest [6]. This makes physisorption the cornerstone technique for determining specific surface area (via BET theory) and characterizing a material's porosity from ~0.35 nm to ~400 nm [6].

Chemisorption: Strong Bonds for Active Site Characterization

Chemisorption, in contrast, involves the formation of a chemical bond—either covalent or ionic—between the adsorbate molecule and the surface atoms of the adsorbent [6] [8]. The enthalpy of adsorption for chemisorption is much higher, comparable to the heat of a chemical reaction, often exceeding 50-800 kJ/mol [8]. This process is typically irreversible under the same conditions of adsorption, as desorption often requires significant energy input and may break chemical bonds or result in the release of different species [6] [8]. A defining feature of chemisorption is its specificity; it only occurs on surfaces where specific chemical bonds can form, leading to a monolayer of adsorbate [8]. This specificity is crucial in catalysis, as it allows researchers to probe the number, type, and strength of a catalyst's active sites [9].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Physisorption and Chemisorption

| Characteristic | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Forces Involved | Van der Waals | Covalent or Ionic Bonds |

| Enthalpy (kJ/mol) | 5 - 50 (similar to liquefaction) [8] | 50 - 800 (similar to chemical reactions) [8] |

| Reversibility | Reversible [6] [8] | Irreversible [6] [8] |

| Specificity | Non-specific [8] | Highly specific [8] |

| Adsorbate Layer | Multilayer [6] | Monolayer [8] |

| Temperature Dependence | Favored at low temperatures [8] | Can occur at higher temperatures [8] |

| Primary Application | Surface area, porosity [6] | Active sites, catalytic activity [9] |

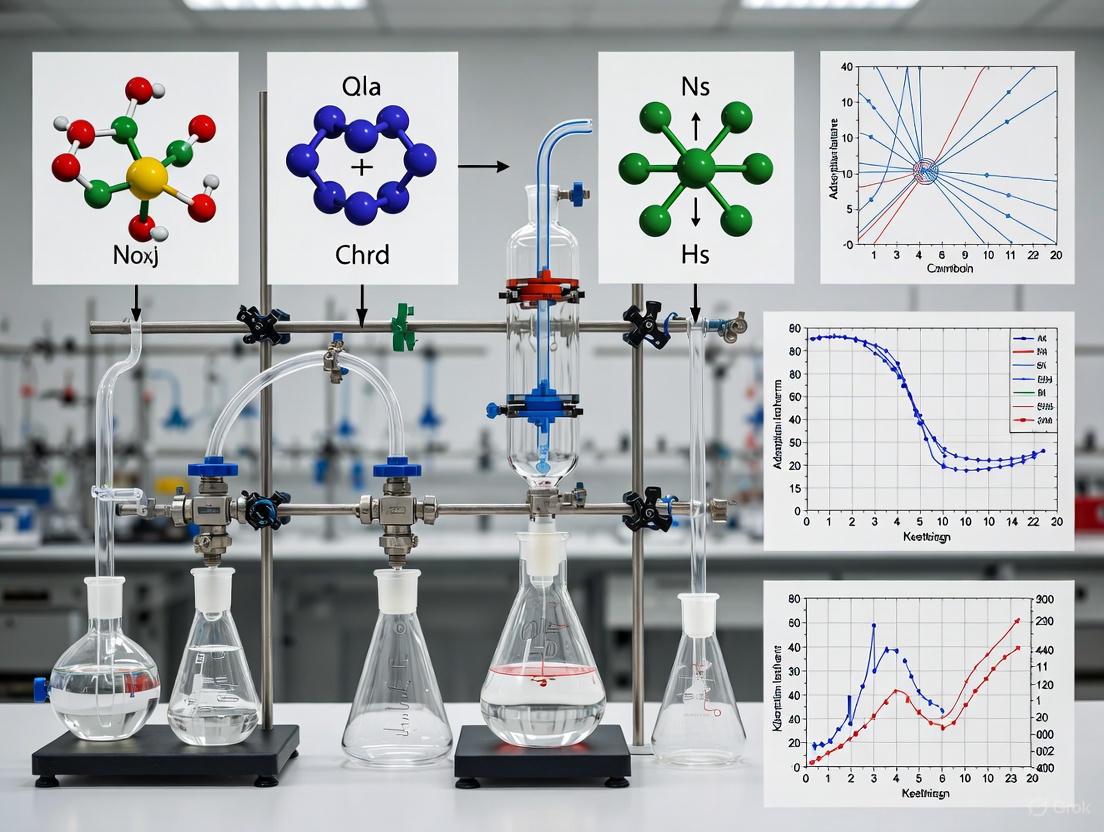

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for distinguishing physisorption from chemisorption, outlining key diagnostic criteria.

Experimental Protocols for Adsorption Analysis

Protocol for Physisorption Analysis (BET Surface Area and Porosity)

Objective: To determine the specific surface area, pore size distribution, and total pore volume of a catalyst or pharmaceutical powder using nitrogen physisorption at 77 K.

Principle: This method uses the static volumetric technique [10]. The sample is placed in a sealed system, and the amount of gas adsorbed is determined by measuring pressure changes at a constant temperature (typically liquid nitrogen temperature, 77 K) as the relative pressure is increased [6] [10]. Data is collected in the form of an adsorption isotherm, which is then analyzed using models like BET (for surface area) and DFT/BJH (for porosity) [6] [10].

Materials and Equipment:

- Gas Adsorption Analyzer: e.g., Micromeritics 3Flex, ASAP 2460, or TriStar II Plus [6] [9].

- Sample Tubes: With sealed, evacuated bottoms.

- Gases: High-purity (≥99.99%) N₂ (standard) or Kr (for low surface areas <1 m²/g) [6].

- Cryogen: Liquid nitrogen in a Dewar.

- Degassing Unit: Separate or integrated preparation station.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Weigh an appropriate amount of sample (enough to provide a total surface area of 5-100 m²) into a clean, dry sample tube.

- Sample Degassing: Seal the sample tube to the degassing port. Apply heat and vacuum to remove moisture and contaminants from the sample surface. A common protocol is 150°C under vacuum for 6-12 hours, but this must be optimized to avoid structural damage. Cool to room temperature.

- Weighing: Precisely weigh the degassed sample tube.

- Analysis Setup: Transfer the sample tube to the analysis port of the instrument. Immerse the sample bulb in a liquid nitrogen Dewar to maintain a constant temperature of 77 K throughout the analysis.

- Isotherm Measurement: The instrument automatically introduces precise doses of N₂ into the sample cell and measures the equilibrium pressure. This process continues from a very low relative pressure (P/P₀ ~10⁻⁶) up to near-saturation pressure (P/P₀ ~0.99) [6].

- Data Analysis:

- BET Surface Area: Use the linearized BET equation on the adsorption data in the relative pressure range of 0.05-0.30 P/P₀ to calculate the monolayer capacity and subsequently the specific surface area [6].

- Pore Size Distribution: Apply advanced models such as Density Functional Theory (DFT) or the Barrett, Joyner, and Halenda (BJH) method to the full isotherm to calculate pore size distributions for micropores (<2 nm), mesopores (2-50 nm), and macropores (>50 nm) [6].

Protocol for Chemisorption Analysis (Active Metal Dispersion)

Objective: To quantify the number of active sites, active metal surface area, and metal dispersion of a supported metal catalyst (e.g., Pt/Al₂O₃) using pulsed or static chemisorption.

Principle: A probe gas (e.g., H₂ for metals like Pt, Ni; CO for others) is dosed onto a freshly reduced catalyst sample. The gas chemisorbs selectively to the metal active sites in a monolayer. By measuring the volume of gas consumed, the number of active sites can be calculated [9].

Materials and Equipment:

- Chemisorption Analyzer: e.g., Micromeritics AutoChem III or 3Flex with chemisorption capabilities [9].

- Gases: High-purity H₂, CO, O₂, and an inert carrier gas like He or Ar.

- Reduction Furnace: Integrated with the analyzer for in-situ pre-treatment.

- Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD): For quantifying gas uptake in pulse chemisorption.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Loading: Weigh 50-200 mg of catalyst and load it into a U-shaped quartz sample tube.

- In-Situ Pre-treatment/Reduction: Flow a reducing gas (e.g., 5% H₂ in Ar) over the sample while ramping the temperature to a predefined value (e.g., 400°C) at a controlled rate (e.g., 10°C/min). Hold at this temperature for 1-2 hours to reduce the metal oxide to its active metallic state.

- Purging: Flush the system with an inert gas (Ar) at the reduction temperature to remove any residual H₂, then cool to the analysis temperature (e.g., 35°C or 100°C).

- Pulse Chemisorption:

- Calibrate the TCD response by injecting known volumes of the probe gas into the inert carrier stream.

- Inject repeated pulses of the probe gas (e.g., 5% H₂ in Ar) over the sample until the peak areas from two consecutive pulses are identical, indicating surface saturation.

- The total volume of gas chemisorbed is the sum of the volumes from all pulses before saturation.

- Data Analysis:

- Uptake Calculation: Calculate the total volume of gas adsorbed from the pulse data.

- Metal Dispersion: Assuming a stoichiometry (e.g., one H atom per surface metal atom, H:Mₛ = 1:1), calculate the number of surface metal atoms. Dispersion (%) = (Number of surface metal atoms / Total number of metal atoms) × 100.

- Active Metal Surface Area: Calculate the surface area of the active metal per gram of catalyst.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for sample preparation and analysis via physisorption or chemisorption.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Gas Adsorption Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen (N₂), 99.99% | Standard adsorbate for physisorption; used for BET surface area and mesopore analysis at 77 K [6]. | Standard surface area and porosity for most catalysts, pharmaceuticals, and porous materials [6] [7]. |

| Krypton (Kr), 99.99% | Adsorbate for low surface area materials (<1 m²/g); its lower vapor pressure allows for more accurate measurement [6]. | Characterization of dense ceramics, non-porous catalysts, and certain metal powders [6]. |

| Carbon Dioxide (CO₂), 99.99% | Probe molecule for ultramicropores and surface chemistry at 273 K [6] [10]. | Analysis of carbon-based materials, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and narrow micropores [6]. |

| Hydrogen (H₂), 99.99% | Standard probe gas for chemisorption on metal surfaces (e.g., Pt, Pd, Ni) [10] [9]. | Determination of metal dispersion, active surface area, and uptake capacity for energy storage [9]. |

| Carbon Monoxide (CO), 99.99% | Probe gas for chemisorption; can distinguish between different types of metal sites based on bonding geometry [9]. | Characterization of supported metal catalysts (e.g., Co, Fe). |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Cryogen to maintain a constant temperature of 77 K for N₂ and Ar physisorption [6] [10]. | Essential for almost all physisorption measurements. |

| Sample Tubes & Cells | Sealed, evacuated containers that hold the sample during analysis and degassing. | Required for all sample analyses. |

| Quantachrome/Micromeritics etc. | Advanced software packages that control instruments and implement data analysis models (BET, DFT, BJH, etc.) [10]. | Data acquisition, isotherm analysis, and report generation for all applications. |

Advanced Concepts and Future Trends

The field of gas adsorption continues to evolve beyond the classic physisorption/chemisorption dichotomy. A groundbreaking development is the discovery of mechanisorption, where molecules are actively pumped onto surfaces using artificial molecular machines to form mechanical bonds, far from thermodynamic equilibrium [11]. This new mode of adsorption, first reported in 2021, promises revolutionary applications in energy storage (e.g., for hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane) and chemical separations [11].

Technologically, several key trends are shaping the future of gas adsorption analysis:

- In-Situ and Operando Analysis: Measurements under real reaction conditions (e.g., during catalysis) are gaining prominence to provide more relevant mechanistic insights [10].

- Automation and High-Throughput: Modern analyzers support automated sample preparation and sequential analysis of multiple samples, drastically improving productivity in R&D and quality control [10].

- AI and Machine Learning: AI algorithms are being explored to enhance data interpretation, predict material performance, and accelerate R&D cycles [10].

- Multi-Gas and Environmental Focus: There is a growing demand for analyzing adsorption behavior with gases relevant to energy and the environment, such as H₂, CH₄, and CO₂, for applications in fuel cells, gas storage, and carbon capture [10].

Application in Catalyst and Material Development

The distinct information provided by physisorption and chemisorption is instrumental across various industries. In catalyst development, chemisorption data directly informs the design of catalysts with higher activity and selectivity, leading to reported yield improvements of up to 20% and reduced operational costs [7] [9]. In energy storage, physisorption is used to optimize the pore structure of activated carbons in supercapacitors, potentially increasing energy density by up to 30% [7]. For environmental remediation, physisorption principles guide the design of adsorbents like activated carbon and zeolites for removing pollutants from air and water, with removal efficiencies often exceeding 95% [7] [8]. Finally, in the pharmaceutical industry, physisorption techniques are critical for assessing the porosity and surface area of drug carriers and excipients, which directly influence drug release profiles and bioavailability [6] [7].

Within catalyst characterization research, understanding the fundamental physical properties of a material is essential for correlating its structure with its performance. Gas adsorption techniques serve as a cornerstone for determining several of these key properties non-destructively. This application note details the protocols and methodologies for measuring surface area, pore size distribution, metal dispersion, and crystallite size, framing them within the comprehensive characterization of heterogeneous catalysts. The accurate determination of these parameters provides researchers and development professionals with the insights needed to optimize catalytic materials for enhanced activity, selectivity, and stability [12].

Surface Area Analysis via Gas Physisorption

The specific surface area of a catalyst is a critical property, as it represents the landscape where catalytic reactions occur. The most widely accepted method for its determination is the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) theory, which models the multilayer adsorption of gas molecules on a solid surface [6] [13].

Experimental Protocol for BET Surface Area Measurement

- Sample Preparation: The sample must be thoroughly cleaned to remove any contaminants (e.g., water, vapors) that might occupy active surfaces. This is achieved through a combination of heat and vacuum or inert gas flow (degassing). The temperature and duration of degassing are critical and depend on the sample's thermal stability [13].

- Analysis Conditions: The prepared sample is cooled to cryogenic temperatures (typically using liquid nitrogen at 77 K or liquid argon at 87 K) and placed under vacuum. The cryogenic temperature enhances the interaction between the gas molecules and the sample surface [13].

- Data Collection: Known quantities of an inert probe gas (e.g., N₂, Kr) are sequentially dosed into the sample cell. The system monitors the pressure before and after each dose, and the difference is used to calculate the volume of gas adsorbed onto the sample surface. Data is collected as an adsorption isotherm—a plot of the quantity adsorbed versus relative pressure (P/P₀) [6] [13].

- Data Analysis: The data points within the relative pressure range of approximately 0.05–0.30 are linearized using the BET equation. The monolayer capacity, which is the volume of gas required to form a single molecular layer on the surface, is derived from the slope and intercept of this linear plot. The specific surface area is then calculated using the known cross-sectional area of the adsorbate gas molecule [6] [13].

Selection of Analysis Gas

The choice of adsorbate is crucial for obtaining accurate results and is primarily determined by the sample's expected surface area and chemical nature.

Table 1: Guide to Selecting an Analysis Gas for Surface Area Measurement

| Adsorptive Gas | Analysis Temperature | Primary Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen (N₂) | 77 K | Standard for surface area ≥ 1 m²/g [13] | Has a quadrupole moment that can interact with surface functional groups, potentially leading to inaccuracies for polar materials [14]. |

| Argon (Ar) | 87 K | IUPAC-recommended for microporous and polar materials (zeolites, MOFs, metal oxides) [14] | Monoatomic and lacks a dipole, eliminating specific surface interactions. Can reduce analysis time by up to 50% compared to N₂ [14]. |

| Krypton (Kr) | 77 K | Low surface area materials (< 0.5 m²/g) [6] [14] [13] | Its low saturation pressure allows for more accurate measurement of the small pressure changes associated with low surface areas [13]. |

The following workflow outlines the decision path for selecting the appropriate gas and technique based on the catalyst's properties and the information required.

Pore Size Distribution Analysis

The pore network of a catalyst directly influences mass transport, reactant accessibility, and often the selectivity of reactions. Gas physisorption is the primary technique for characterizing pores across the microporous (< 2 nm), mesoporous (2–50 nm), and macroporous (> 50 nm) ranges [6] [15].

Experimental Protocol and Data Interpretation

The experimental procedure for generating an adsorption isotherm is identical to the first three steps outlined in Section 2.1. For pore size analysis, the isotherm is typically measured from very low relative pressure (~0.00001) up to saturation (~0.995) to capture the complete pore-filling process [6].

- Isotherm Analysis: The adsorption isotherm is analyzed using various mathematical models to extract pore size information. As gas pressure increases, pores fill via capillary condensation, with smaller pores filling before larger ones [15].

- Model Selection: The appropriate model for calculating the pore size distribution depends on the pore width of the material.

- Micropores (< 2 nm): Density Functional Theory (DFT) is considered the state-of-the-art model. Classical methods such as the t-plot (for total micropore area and volume) and Dubinin plots are also used [6] [15].

- Mesopores (2–50 nm): The Barrett, Joyner, and Halenda (BJH) method is a widely used classical model. DFT and the Dollimore-Heal (DH) method are also applicable and can provide more accurate results [6].

- Macropores (> 50 nm): While BJH and DFT can be extended, mercury intrusion porosimetry is often the preferred technique for pores larger than 400 nm [6].

Table 2: Standard Models for Pore Size Distribution Analysis [6]

| Pore Classification | Pore Size Range | Typical Calculation Models |

|---|---|---|

| Micropore | < 2 nm | Density Functional Theory (DFT), t-plot, Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R), Horvath-Kawazoe (H-K) |

| Mesopore | 2 – 50 nm | Barrett, Joyner, and Halenda (BJH), Density Functional Theory (DFT), Dollimore-Heal (DH) |

| Macropore | > 50 nm | Barrett, Joyner, and Halenda (BJH), Density Functional Theory (DFT), Dollimore-Heal (DH) |

Metal Dispersion and Active Site Counting via Chemisorption

While physisorption measures the total surface area, chemisorption is used to quantify the fraction of the surface comprised of specific active sites, typically metallic centers in a catalyst. This technique relies on the formation of strong, specific chemical bonds between a probe gas and the active sites, resulting in a monomolecular layer [16].

Pulse Chemisorption Protocol

The pulse chemisorption technique is a dynamic method widely used to quantify active sites.

- Sample Pre-treatment: The catalyst sample is often pre-reduced in a stream of hydrogen at elevated temperature to ensure the active metal is in its reduced, metallic state [16].

- Purge and Cool: An inert gas (e.g., He, Ar) flows through the sample to remove any residual reductant. The sample is then cooled to the analysis temperature (often ambient) [16].

- Gas Dosing and Measurement: Precisely calibrated pulses of a probe gas (e.g., H₂, CO, O₂) are injected into the inert carrier gas stream flowing over the sample. A Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) downstream measures the gas concentration. When a pulse is injected, the active sites adsorb the probe gas, resulting in a diminished or absent detector peak [16].

- Saturation and Calculation: The pulsing continues until the sample is saturated, indicated by consecutive peaks having identical areas. The total volume of gas chemisorbed is calculated from the sum of the volumes adsorbed from each pulse. From this, metal dispersion (the percentage of metal atoms on the surface), metallic surface area, and average crystallite size can be derived using known stoichiometries between the probe gas and the metal atom [16].

Selection of Probe Gas for Chemisorption

The choice of probe gas is critical and depends on the metal being characterized and the desired stoichiometry.

- Hydrogen (H₂): Commonly used for metals like Pt and Ni. It typically dissociates, yielding a stoichiometry of one H atom per surface metal site (H/Mₛ = 1) [16].

- Carbon Monoxide (CO): Used for metals like Pd, where H₂ may form hydrides. CO can bind in linear (one CO per metal atom) or bridged (one CO per two metal atoms) configurations, so the stoichiometry must be carefully considered [16].

- Nitrous Oxide (N₂O): Used for metals with negligible affinity for H₂ or CO, such as Cu and Ag. N₂O can be used for selective surface oxidation, which is then followed by a second technique like H₂ titration to quantify the oxygen uptake [16].

Crystallite Size Determination

Crystallite size is a fundamental property that influences catalytic activity and stability. While direct imaging techniques like transmission electron microscopy (TEM) provide visual information, X-ray diffraction (XRD) offers a bulk-average measurement based on the principle of peak broadening.

XRD Analysis Protocol and Methods

- Data Collection: An XRD pattern of the catalyst sample is collected over a appropriate 2θ range.

- Peak Broadening Analysis: The width of the diffraction peaks is inversely related to the crystallite size. This broadening is quantified and separated from strain-induced broadening using various mathematical models [17].

- Size Calculation Models:

- Scherrer Method: The simplest model, providing a volume-averaged crystallite size. It does not account for strain and can underestimate size [17].

- Williamson-Hall (W-H) Method: Deconvolutes size-induced and strain-induced broadening by analyzing the peak width as a function of diffraction angle [17].

- Size-Strain Plot (SSP) and Halder-Wagner (H-W) Method: More sophisticated models that are considered robust for providing accurate size predictions, especially in strain-sensitive systems [17].

Comparative studies on materials like nickel ferrites have shown that while the Scherrer method yields the smallest sizes, W-H, H-W, and SSP methods can predict significantly larger sizes due to their consideration of microstrain, making them preferable for accurate characterization [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogs key materials and their functions in gas adsorption and catalyst characterization experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Catalyst Characterization

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Nitrogen Gas (N₂), 99.99% | Primary adsorbate for BET surface area and mesopore analysis of medium-to-high surface area materials [14] [13]. |

| Argon Gas (Ar), 99.99% | IUPAC-recommended adsorbate for micropore and surface area analysis of polar materials, reducing specific interactions and analysis time [14]. |

| Carbon Dioxide (CO₂), 99.99% | Probe gas for analyzing very small micropores (< 0.5 nm) in carbons at 273 K, complementary to N₂/Ar analysis [14] [15]. |

| Krypton Gas (Kr), 99.99% | Adsorbate for accurate surface area measurement of low surface area materials (< 0.5 m²/g) due to its low saturation pressure [6] [14] [13]. |

| Hydrogen Gas (H₂), 10% in Ar/He | Primary reductant for catalyst pre-treatment and common probe gas for pulse chemisorption of metals like Pt and Ni [16] [18]. |

| Carbon Monoxide (CO), 10% in He | Probe gas for pulse chemisorption, used for metals like Pd and to study different binding configurations on Pt [16]. |

| Nitrous Oxide (N₂O) | Probe gas for pulse chemisorption on metals with low affinity for H₂/CO, such as Cu and Ag [16]. |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Common cryogen for maintaining a constant temperature bath at 77 K during physisorption analyses [14]. |

| Liquid Argon | Cryogen for maintaining analysis temperature at 87 K, as recommended by IUPAC for Ar adsorption [14]. |

| Metal-Oxide Supports (e.g., γ-Al₂O₃, SiO₂) | High-surface-area, inert carriers for dispersing active metal phases (e.g., Pt, Ni) to create supported catalysts [18]. |

The suite of gas adsorption techniques provides an indispensable toolkit for the comprehensive characterization of catalytic materials. By applying the detailed protocols for BET surface area, pore size distribution, and pulse chemisorption, researchers can accurately quantify the physical landscape and concentration of active sites. When coupled with XRD for crystallite size determination, a multi-faceted picture of the catalyst's structure emerges. Mastery of these methods, including the judicious selection of probe gases and analytical models as outlined in this note, enables the rational design and optimization of catalysts for applications ranging from chemical synthesis to drug development.

Within catalyst characterization research, adsorption isotherms are fundamental tools for quantifying critical physical properties that dictate catalytic performance. These isotherms graphically represent the relationship between the quantity of a gas adsorbed on a solid surface and its equilibrium pressure at a constant temperature [19]. The interpretation of these curves provides essential insights into the catalyst's surface area, pore structure, and active site characteristics [20]. While physical adsorption (physisorption), resulting from weak van der Waals forces, is typically used to analyze the catalyst support structure, chemical adsorption (chemisorption) involves the formation of a strong chemical bond and is highly selective for probing the active metal surfaces responsible for catalytic activity [3] [19]. The ability to distinguish between these mechanisms and correctly interpret the isotherm data is therefore critical for the rational design and evaluation of heterogeneous catalysts.

Fundamentals of Adsorption Isotherms

Distinguishing Physisorption and Chemisorption

A clear understanding of the differences between physical and chemical adsorption is a prerequisite for accurate catalyst characterization. The nature of the adsorbate-adsorbent interaction dictates the analytical information that can be obtained.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Physisorption and Chemisorption

| Characteristic | Physical Adsorption (Physisorption) | Chemical Adsorption (Chemisorption) |

|---|---|---|

| Bonding Forces | Weak van der Waals forces | Strong chemical bonding |

| Enthalpy of Adsorption | Low (typically < 80 kJ/mol) | High (typically 80-800 kJ/mol) |

| Specificity | Non-specific, occurs on all surfaces | Highly specific to certain adsorptive/adsorbent pairs |

| Layer Formation | Multilayer adsorption possible | Typically limited to a monolayer |

| Reversibility | Readily reversible | Often difficult to reverse |

| Primary Application in Catalysis | Characterization of catalyst support structure (surface area, porosity) | Characterization of active metal surfaces (dispersion, active surface area) |

As indicated in Table 1, physisorption is used to characterize the catalyst support structure, revealing information such as the total surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution [19]. Chemisorption, in contrast, is selective, probing only the active areas capable of forming a chemical bond. It is a required step in heterogeneous catalysis, and its measurement provides quantitative information on the active metal surface area, metal dispersion, and average metal crystallite size [3] [19]. Under proper conditions, both phenomena can occur simultaneously, with a layer of molecules physisorbed on top of a chemisorbed layer [19].

Classical Isotherm Models and Their Interpretation

The analysis of adsorption data is guided by well-established models, each with specific assumptions about the adsorbent's surface and the nature of adsorption. The Langmuir and Freundlich models are two of the most widely used for interpreting catalyst adsorption behavior.

Table 2: Classical Adsorption Isotherm Models

| Isotherm Model | Non-Linear Form | Graphical Interpretation & Catalyst Insights |

|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | q_e = (q_m * K_L * C_e) / (1 + K_L * C_e) [21] |

Assumes a homogeneous surface with monolayer adsorption. A plateau in the isotherm indicates complete monolayer coverage, allowing calculation of maximum monolayer capacity (q_m) [21]. |

| Freundlich | q_e = K_F * C_e^(1/n) [21] |

Empirical model for heterogeneous surfaces and multilayer adsorption. A linear plot on a log-log scale suggests surface energy heterogeneity, common in porous catalyst supports [21]. |

| Langmuir-Freundlich (Sips) | q_e = (K_s * C_e^β) / (1 + a_s * C_e^β) [21] |

A hybrid model that can provide a better fit for some adsorption processes on heterogeneous surfaces [21]. |

The Langmuir model is particularly useful for determining the number of accessible active sites, a key parameter in catalysis. The Freundlich model, on the other hand, is more applicable for describing the adsorption on the often-heterogeneous surface of the catalyst support material [21].

Figure 1: A workflow for interpreting adsorption isotherms using classical models to derive catalyst properties.

Experimental Protocols for Catalyst Characterization

The accurate determination of adsorption isotherms requires meticulous experimental procedures. The following protocols outline the standard methods for characterizing catalysts via chemisorption techniques.

Static Volumetric Chemisorption

The static volumetric method is a high-resolution technique for obtaining chemisorption isotherms across a wide pressure range [19].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Approximately 50-100 mg of catalyst sample is loaded into a quartz sample tube. The sample is first subjected to in-situ pre-treatment, which may involve heating under a flow of inert gas or reduction in hydrogen to clean the surface.

- Sample Reduction: The sample is reduced in a flow of hydrogen (e.g., 10% H₂ in Ar) at a specific temperature (e.g., 350°C for a Pt catalyst) for a set duration (e.g., 1-2 hours) to activate the metal phase.

- Evacuation: After reduction, the system is evacuated at the analysis temperature to remove weakly adsorbed species.

- Isotherm Measurement: The sample is maintained at a constant temperature (e.g., 35°C for H₂ chemisorption). Known doses of a probe gas (e.g., H₂ for Pt, Ni, Rh; CO for Pd) are introduced into the calibrated volume. After each dose, the system is allowed to reach equilibrium, and the pressure change is recorded.

- Back-Sorption Isotherm: A second isotherm is measured after a brief evacuation step at the analysis temperature. This step removes the weakly physisorbed molecules.

- Data Analysis: The difference between the first and second isotherms represents the chemically bonded gas. This quantity is used to calculate the metal dispersion, active metal surface area, and average crystallite size [3].

Pulse Chemisorption

Pulse chemisorption is a dynamic flowing-gas technique operating at ambient pressure, valued for its speed and simplicity [19] [22].

Protocol:

- Pre-treatment & Reduction: The catalyst sample is pre-treated and reduced in-situ, as described in the volumetric protocol.

- Saturation with Carrier Gas: After reduction and cooling to the analysis temperature, an inert carrier gas (e.g., He or Ar) is flowed over the sample.

- Gas Pulses: Small, reproducible pulses of the probe gas (e.g., 0.5 mL STP of 10% H₂ in Ar) are injected into the carrier gas stream via a loop injection valve.

- Detection: A thermal conductivity detector (TCD) downstream measures the amount of gas not adsorbed by the catalyst.

- Saturation and Calculation: Pulses are repeated until the detector signal shows no further adsorption, indicating catalyst saturation. The total volume of chemisorbed gas is the sum of the adsorbed quantities from each pulse. This data is used with the known metal loading to calculate percent dispersion using the formula [22]:

D% = (V_ads * F_s * 100 * W_a) / (V_mol * M% * 100)whereV_adsis the volume adsorbed,F_sis the stoichiometry factor,W_ais the atomic weight,V_molis the molar volume, andM%is the metal weight percent.

Figure 2: Pulse chemisorption workflow for rapid catalyst metal dispersion analysis.

Temperature-Programmed Techniques

Temperature-programmed methods provide insights into the strength of interaction between adsorbates and the catalyst surface [20] [22].

Protocol for Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD):

- Adsorption: The catalyst surface is saturated with a probe gas (e.g., NH₃ for acidity, CO₂ for basicity) at a specific temperature.

- Purging: The system is purged with an inert gas to remove any physisorbed molecules.

- Controlled Desorption: The temperature is linearly increased (e.g., 10-30°C/min) under a flow of inert gas.

- Analysis: A TCD or mass spectrometer monitors the desorbed gas as a function of temperature.

- Interpretation: The temperature of desorption peaks indicates the strength of adsorption sites, while the area under the peaks quantifies the number of sites [22]. Multiple peaks reveal the presence of different types of active sites with varying adsorption enthalpies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting adsorption experiments for catalyst characterization.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Adsorption Studies

| Item | Function & Application in Catalyst Characterization |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Probe Gases (H₂, CO, O₂, N₂) | H₂ and CO are used for chemisorption on metals to determine active metal surface area. N₂ at 77 K is the standard for physisorption surface area and porosity analysis [3] [19]. |

| Inert Carrier Gases (He, Ar) | Used as a diluent, for purging, and as a carrier gas in pulse chemisorption and TPD/TPR experiments [22]. |

| Supported Metal Catalysts (e.g., Pt/Al₂O₃) | Common model catalysts for method development and validation. The support (e.g., Al₂O₃, SiO₂, TiO₂) and active metal (e.g., Pt, Pd, Ni) can be varied [22]. |

| Quantachrome Autosorb-iQ / Micromeritics Autochem II | Commercial automated instruments for performing high-resolution volumetric chemisorption, physisorption, and temperature-programmed analyses [3] [22]. |

| Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) | A standard detector for quantifying the concentration of gases in an effluent stream during pulse chemisorption and TPD/TPR experiments [19] [22]. |

| Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer | Used for online analysis of gas mixtures, allowing for the identification of specific desorbed species during temperature-programmed studies [20] [22]. |

Advanced Isotherm Applications and Multicomponent Systems

While single-component isotherms are foundational, real-world catalytic processes often involve multiple adsorbates. The development of models for multicomponent adsorption is an area of growing research relevance [23]. The Jeppu Amrutha Manipal Multicomponent (JAMM) isotherm is a recent model that leverages single-component parameters and incorporates an interaction coefficient and mole fraction term to predict competitive adsorption behavior more comprehensively [23]. Furthermore, temperature-programmed techniques can be combined with high-pressure operation to characterize catalysts under more industrially relevant conditions. For example, Temperature-Programmed Reduction (TPR) at 25 bar can significantly lower the reduction temperature of metal oxides compared to atmospheric pressure, providing valuable insights for catalyst activation [22]. The integration of adsorption isotherm analysis with computational methods, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), is also a powerful approach for simulating adsorption mechanisms and understanding the molecular-level interactions between adsorbates and catalyst surfaces [24].

In the field of catalyst characterization research, gas adsorption techniques are indispensable for probing the structural properties that govern catalytic performance. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) classification system for adsorption isotherms provides researchers with a powerful diagnostic tool for identifying material porosity and surface characteristics [25] [26]. This classification system enables scientists to decode the complex relationship between adsorbent structure and adsorption behavior, offering critical insights into pore architecture, active surface area, and potential catalytic efficiency [19] [27].

The fundamental principle underlying this analytical approach is that the shape of an adsorption isotherm – the relationship between the quantity of gas adsorbed and the equilibrium pressure at constant temperature – reveals specific textural properties of porous materials [25] [28]. Within the context of catalyst characterization, understanding these properties is essential for rational catalyst design, optimization, and performance evaluation [19] [29].

Theoretical Foundations of Adsorption

Physisorption versus Chemisorption

Gas-solid interactions in catalyst characterization occur through two primary mechanisms: physisorption and chemisorption. Understanding their distinctions is crucial for selecting appropriate characterization techniques.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Physisorption and Chemisorption

| Characteristic | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Interaction Forces | Weak van der Waals forces [19] | Strong chemical bonds [19] |

| Enthalpy of Adsorption | Low (20-40 kJ/mol) [28] | High (40-800 kJ/mol) [19] [28] |

| Specificity | Non-specific [19] | Highly selective [19] |

| Layer Formation | Multilayer possible [19] [28] | Monolayer typically [19] [28] |

| Reversibility | Easily reversible [19] | Difficult to reverse [19] |

| Temperature Dependence | Occurs at lower temperatures [19] [28] | Requires higher temperatures [19] |

Physisorption analyzes the overall surface structure, including total surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution, making it particularly valuable for evaluating catalyst support structures [19]. In contrast, chemisorption selectively probes active surfaces capable of forming chemical bonds with specific probe molecules, providing information about active sites crucial for catalytic function [19] [29].

The IUPAC Classification System

The IUPAC classification system categorizes adsorption isotherms into eight distinct types (I-VI, with subtypes), each corresponding to specific material porosity and surface characteristics [25] [26]. This systematic classification enables researchers to make informed inferences about a material's porous architecture directly from isotherm shape.

Table 2: IUPAC Isotherm Classification and Material Properties

| IUPAC Type | Isotherm Shape | Pore Structure | Material Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| I(a) | Microporous, plateau at high P/P₀ | Narrow microporous (<1 nm) [26] | Zeolites [25] |

| I(b) | Microporous | Microporous [25] | Activated carbon [25] |

| II | Non-porous or macroporous | Non-porous or macroporous [25] [28] | Nonporous silica, magnetic powder [25] |

| III | Weak adsorbate-adsorbent interaction | Non-porous with weak interactions [28] | Graphite/water systems [25] |

| IV(a) | Mesoporous with hysteresis | Mesoporous (2-50 nm) [25] [27] | Mesoporous silica, alumina [25] |

| IV(b) | Mesoporous without hysteresis | Mesoporous with pore diameter <4 nm [25] | MCM-41 [25] |

| V | Porous with weak interactions | Porous materials with weak interactions [25] [28] | Activated carbon/water [25] |

| VI | Step-wise layer formation | Homogeneous surface [25] | Graphite/Kr, NaCl/Kr [25] |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for porosity determination using the IUPAC classification system:

Experimental Protocols for Isotherm Analysis

Sample Preparation and Pretreatment

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining accurate and reproducible adsorption data. The following protocol outlines essential steps for catalyst characterization:

Sample Outgassing: Remove previously adsorbed contaminants and moisture by heating the sample under vacuum (typically 10⁻² to 10⁻³ Torr) at elevated temperatures for several hours (typically 150-300°C depending on material stability) [19].

Surface Cleaning: Ensure the chemically active surface is cleaned of previously adsorbed molecules to enable specific chemisorption interactions [19].

Mass Determination: Precisely weigh the clean, dry sample (typically 50-200 mg) after outgassing and cooling to room temperature in an inert atmosphere.

Surface Activation: For chemisorption studies, activate the catalyst surface through appropriate treatments (oxidation, reduction, or other means) based on the catalytic system [19].

Static Volumetric Method

The static volumetric technique is a widely employed method for obtaining high-resolution chemisorption isotherms across a broad pressure range [19].

Table 3: Static Volumetric Method Protocol

| Step | Procedure | Parameters | Quality Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equipment Setup | Fill sample tube with degassed catalyst; mount in analysis port | Sample mass: 50-200 mg | Verify system leak rate <10⁻⁵ mbar/min |

| System Evacuation | Evacuate sample and manifold to high vacuum | Pressure: <10⁻³ Torr; Temperature: 25°C | Base pressure stability indicates proper outgassing |

| Dose Introduction | Admit precise quantities of adsorptive to sample | Initial dose: 0.5-5 cm³/g STP | Allow sufficient equilibration time (10-300 s) |

| Equilibrium Monitoring | Monitor pressure decay until equilibrium | Equilibration criteria: <0.01 Torr/min change | Track time to equilibrium for kinetic assessment |

| Data Point Collection | Record equilibrium pressure and adsorbed quantity | Pressure range: 0-950 Torr | Multiple points at low P for accurate monolayer determination |

| Isotherm Construction | Repeat dosing until full pressure range covered | Temperature: 25-100°C typical | Reproducibility check via adsorption-desorption cycles |

Dynamic (Pulse) Chemisorption Method

The dynamic technique operates at ambient pressure and is particularly suitable for temperature-programmed analyses [19].

Sample Preparation: Prepare and pretreat the catalyst sample as described in Section 3.1.

Carrier Gas Flow: Establish a stable flow of inert carrier gas (typically 20-50 mL/min) through the sample bed.

Pulse Calibration: Calibrate the injection system and thermal conductivity detector (TCD) using standard reference materials.

Gas Dosing: Introduce small, precise pulses of probe gas (H₂, CO, O₂, etc.) onto the sample bed using a calibrated injection loop.

Saturation Detection: Monitor the effluent gas with TCD until detected peaks match injected quantities, indicating surface saturation.

Uptake Calculation: Calculate chemisorption capacity by summing the quantities adsorbed from each pulse.

Temperature-Programmed Techniques

Temperature-programmed methods provide complementary information about surface energy and reactivity:

Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD): Adsorb probe gas at low temperature, then program temperature upward while monitoring desorbed species.

Temperature-Programmed Reduction (TPR): Monitor consumption of reducing gas (typically H₂) during temperature ramp to characterize reducible species.

Temperature-Programmed Oxidation (TPO): Monitor oxygen consumption during temperature ramp to characterize oxidizable surface sites.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Isotherm Model Fitting

Selecting appropriate mathematical models for isotherm data fitting is essential for accurate surface characterization. Statistical analyses have identified optimal models for each IUPAC isotherm type [26] [30]:

Table 4: Recommended Isotherm Models by IUPAC Classification

| IUPAC Type | Optimal Model | Alternative Models | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type-I(a) | Tóth [30] | Modified BET [26] | Micropore volume, heterogeneity parameter |

| Type-I(b) | Tóth [26] [30] | D-A, Langmuir, Modified D-A [26] | Monolayer capacity, surface heterogeneity |

| Type-II | Modified BET [26] | - | Multilayer capacity, BET constant |

| Type-III | GAB [26] [30] | - | Monolayer capacity, interaction parameter |

| Type-IV(a) | Universal [30] | Ng et al. model [26] | Mesopore volume, hysteresis loop parameters |

| Type-IV(b) | Universal [30] | Ng et al. model [26] | Pore condensation pressure, pore size |

| Type-V | Sun and Chakraborty [26] [30] | - | S-shaped curve parameters, interaction energy |

| Type-VI | Yahia et al. [26] [30] | - | Stepwise adsorption parameters, layer energy |

Advanced Statistical Analysis

Rigorous statistical methods should be employed to validate model selection and parameter sensitivity:

Error Analysis: Calculate root mean square deviation (RMSD) and hybrid fractional error function (HYBRID) to evaluate model fit [26] [30].

Sensitivity Analysis: Employ simulation approaches with multivariate normal distribution to assess parameter uncertainty [30].

Information Criterion: Apply Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) or Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to balance model complexity and goodness-of-fit [26].

Statistical Testing: Implement ANOVA, Tukey HSD tests, Kruskal-Wallis, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to identify statistically significant optimal models [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Research Reagents and Instrumentation for Adsorption Studies

| Reagent/Instrument | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Gases | Selective characterization of surface properties | N₂ (physisorption, 77 K), H₂ (metal surface area), CO (metal dispersion), Ar (micropore analysis) |

| Reference Materials | Instrument calibration, method validation | Certified surface area standards, porous reference materials |

| Static Volumetric Analyzer | High-resolution isotherm measurement | Automated systems with precise pressure transducers, temperature control |

| Dynamic Chemisorption System | Pulse chemisorption, temperature-programmed techniques | Thermal conductivity detector, mass flow controllers, temperature programmer |

| Sample Preparation Station | Sample degassing and pretreatment | High vacuum capability, temperature-controlled heating |

| Microporous Materials | Catalyst supports, molecular sieves | Zeolites, activated carbons, MOFs |

| Mesoporous Materials | High-surface-area catalyst supports | Mesoporous silica, alumina, templated materials |

| Non-porous Standards | Surface area reference materials | Nonporous silica, alumina |

Application to Catalyst Characterization

The integration of IUPAC isotherm analysis into catalyst characterization workflows provides critical insights for catalyst development and optimization. The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive experimental workflow for catalyst characterization using gas adsorption techniques:

Hierarchically Structured Porous Catalysts

Advanced catalyst systems often incorporate hierarchically structured porous materials containing multiple levels of porosity spanning micro-, meso-, and macroscales [27]. These materials offer significant advantages for catalytic applications:

Enhanced Mass Transport: Interconnected hierarchical porosity reduces diffusion limitations, improving reactant access to active sites [27].

Optimized Active Site Distribution: Strategic placement of active components across different pore hierarchies enhances catalytic efficiency [27].

Improved Stability: Hierarchical structures can better accommodate volume and thermal variations during catalytic cycles, enhancing catalyst lifetime [27].

The IUPAC isotherm classification system is particularly valuable for characterizing these complex materials, as different regions of the isotherm correspond to specific hierarchical levels within the pore structure.

Correlation with Catalytic Performance

Understanding the relationship between adsorption characteristics and catalytic performance enables rational catalyst design:

Active Site Accessibility: Type I isotherms with sharp initial uptake indicate microporous structures that may limit access to bulky reactants, while Type IV isotherms suggest mesoporous networks favorable for mass transport [25] [27].

Surface-Bonding Energy: Isotherm shape provides insights into adsorbate-adsorbent interaction strength, which correlates with catalytic activity and product selectivity [19].

Site Density and Distribution: The uptake capacity at monolayer coverage quantifies available active sites, while isotherm steps (Type VI) indicate uniform surface energies beneficial for selective catalysis [25] [26].

By applying the protocols and analysis methods outlined in this document, researchers can establish critical structure-property relationships that guide the development of advanced catalytic materials with optimized performance characteristics.

Methodology in Practice: Techniques, Protocols, and Data Analysis

The characterization of solid catalysts is paramount to understanding and optimizing their performance in industrial processes such as fuel production, chemical synthesis, and environmental remediation. Gas adsorption is a cornerstone analytical technique in this field, providing critical information about the catalyst's active surface area, pore structure, and the strength of its interaction with reactant molecules. The process involves the adhesion of gas or vapor molecules (the adsorbate) to the solid surface of the catalyst (the adsorbent) [19]. This phenomenon can be broadly classified into physical adsorption (physisorption), resulting from weak van der Waals forces, and chemical adsorption (chemisorption), which involves the formation of a strong, chemical bond between the adsorbate and the adsorbent [19] [31].

Selecting the appropriate adsorption technique is a critical decision for researchers. The choice hinges on the specific catalytic property under investigation. This application note provides a detailed comparison of the three principal gas adsorption methods—volumetric, gravimetric, and carrier gas—framing them within the context of catalyst characterization research. It offers structured protocols to guide scientists in selecting and implementing the right technique for their specific needs, enabling the precise measurement of properties such as metal surface area, dispersion, active site concentration, and textural properties.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Analysis

The three primary techniques for measuring gas adsorption—volumetric, gravimetric, and carrier gas—operate on distinct physical principles to quantify the amount of gas taken up by a solid catalyst.

- Volumetric Method: This technique, also known as the manometric method, is based on measuring the pressure change in a known, fixed volume of gas before and after exposure to the catalyst sample. The quantity of gas adsorbed is calculated using the real gas law from the observed pressure drop, assuming constant temperature and volume [32]. This method is conducted under static, equilibrium conditions and is renowned for its high-resolution isotherm data across a wide pressure range [19].

- Gravimetric Method: This approach directly measures the mass change of the solid sample as it adsorbs gas molecules. The experiment is typically performed using a highly sensitive microbalance [32]. Like the volumetric method, it is a static technique that provides high-resolution adsorption isotherms. A modern variation employs a Tapered Element Oscillating Microbalance (TEOM), where mass changes are determined by monitoring the frequency changes of an oscillating element in a fixed-bed reactor, even as reaction gases flow through the sample [32].

- Carrier Gas Method: This is a dynamic technique where an inert gas, such as helium or nitrogen, continuously flows over the catalyst sample, serving as a mobile phase. Small, precise pulses of the probe gas (the adsorptive) are injected into this carrier stream. The amount of gas not adsorbed by the sample is then detected, often by a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD). The adsorbed quantity is determined by summing the uptake from each pulse until the sample is saturated, a process known as pulse chemisorption [19] [32].

Table 1: Core Principles and Characteristics of Gas Adsorption Techniques

| Feature | Volumetric Method | Gravimetric Method | Carrier Gas Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Pressure change at constant volume and temperature | Mass change of the sample | Amount of non-adsorbed gas in a carrier stream |

| Primary Principle | Gas laws (PV=nRT) | Mass balance | Gas chromatography / material balance |

| System State | Static | Static | Dynamic (flowing gas) |

| Typical Pressure Range | High vacuum to atmospheric pressure | High vacuum to high pressure | Ambient pressure |

| Key Strength | High-resolution isotherms; wide pressure range | Direct mass measurement; coupled thermal analysis | Speed, simplicity; no vacuum system required |

The choice of technique directly impacts the type and quality of data obtained. Volumetric and gravimetric methods are well-suited for obtaining detailed adsorption isotherms, which are essential for textural analysis like BET surface area and pore size distribution [31]. The carrier gas method, particularly in its pulse chemisorption mode, is highly efficient for rapidly determining metal dispersion and active surface area [19]. Furthermore, the carrier gas framework is uniquely adaptable for Temperature-Programmed analyses, including Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD), Reduction (TPR), and Oxidation (TPO), which provide insights into surface reactivity and metal-support interactions [19].

Table 2: Application-Oriented Comparison for Catalyst Characterization

| Parameter | Volumetric | Gravimetric | Carrier Gas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Speed | Slow (requires equilibrium at each pressure point) | Slow (requires equilibrium at each pressure point) | Fast (non-equilibrium, flow-through) |

| Equipment Complexity | High (requires high-vacuum system) | High (requires sensitive microbalance) | Low to Moderate (operates at ambient pressure) |

| Suitability for BET Surface Area | Excellent | Excellent | Limited |

| Suitability for Chemisorption (Metal Dispersion) | Excellent | Excellent | Very Good (standard for routine analysis) |

| Suitability for Temperature-Programmed Studies | Possible but complex | Possible but complex | Excellent (the primary method) |

| Sample Throughput | Low | Low | High |

Experimental Protocols

The following protocols provide generalized procedures for catalyst characterization. Specific parameters (temperature, gas type, etc.) must be optimized for the material system under study.

Protocol for Volumetric Chemisorption Analysis

Aim: To determine the active metal surface area and dispersion of a supported metal catalyst via static volumetric chemisorption.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Catalyst Sample: Powdered supported metal catalyst (e.g., Pt/Al₂O₃, Ni/SiO₂).

- High-Purity Gases: Hydrogen (H₂) or Carbon Monoxide (CO) for chemisorption; Helium (He) for dead volume calibration.

- Analysis Gas: High-purity probe gas (e.g., H₂, CO, O₂).

- Sample Cell: A known-volume, glass or metal tube capable of withstanding vacuum and high temperature.

- Volumetric Analyzer: An automated instrument with a dosing volume, high-accuracy pressure transducers, a vacuum system, and a sample heater.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Weigh an appropriate amount of catalyst (typically 50-200 mg) and load it into the sample cell.

- Sample Pretreatment (Activation): a. Purge the sample with an inert gas (He) at room temperature. b. Heat the sample to a specified temperature (e.g., 300°C) under inert gas flow or vacuum to remove physisorbed water and contaminants. c. Reduce the sample in a flow of H₂ (or oxidize in air/O₂) to activate the metal sites. d. Evacuate the system to high vacuum (<10⁻⁵ mbar) and cool to the analysis temperature (e.g., 35°C for H₂ chemisorption).

- Dead Volume Calibration: a. With the cooled sample under vacuum, introduce small doses of non-adsorbing helium into the sample cell. b. Record the equilibrium pressure after each dose to calculate the free space (dead volume) of the cell containing the sample.

- Chemisorption Analysis: a. Evacuate the system to remove helium. b. Admit a small, known dose of the probe gas (e.g., H₂) from the dosing volume into the sample cell. c. Monitor the pressure until equilibrium is established (pressure stabilizes). d. The amount adsorbed is calculated from the pressure drop, the known dose volume, and system temperature. e. Repeat steps b-d, building a step-wise adsorption isotherm until no further uptake occurs (saturation).

- Data Analysis: The monolayer capacity is estimated from the adsorption isotherm. The metal dispersion, surface area, and particle size are then calculated based on the stoichiometry of gas adsorption per surface metal atom.

Protocol for Gravimetric Chemisorption Analysis

Aim: To directly measure the mass change during gas adsorption on a catalyst to determine uptake and, when combined with calorimetry, heats of adsorption.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Catalyst Sample: Powdered catalyst.

- High-Purity Gases: As in Protocol 3.1.

- Microbalance: An ultra-sensitive balance capable of measuring microgram changes, housed in a controlled environment.

- Sample Hang-Down Tube: A tube suspended from the microbalance into a controlled temperature zone.

- Gas Dosing and Vacuum System: A system for precise gas introduction and system evacuation.

Procedure:

- System Setup: Suspend the sample hang-down tube from the microbalance. Calibrate the balance.

- Sample Loading & Pretreatment: a. Load the catalyst into a pan at the bottom of the hang-down tube. b. Follow a pretreatment procedure similar to the volumetric method (evacuation, heating, reduction/oxidation) while monitoring the mass until it stabilizes.

- Adsorption Measurement: a. Set the system to the desired analysis temperature. b. Introduce the probe gas to a specific pressure. c. Monitor the sample mass in real-time until it reaches a stable equilibrium value. d. Increase the gas pressure to a new set point and repeat the mass measurement. e. Continue this process to construct a full adsorption isotherm.

- Data Analysis: The mass change at each equilibrium point is converted to a volume of gas adsorbed. The data is processed similarly to the volumetric method to extract monolayer capacity and surface properties. If coupled with calorimetry, the simultaneous measurement of heat flow provides the enthalpy of adsorption.

Protocol for Pulse Chemisorption in a Carrier Gas

Aim: To rapidly determine the metal dispersion and active surface area of a catalyst using a dynamic flow method.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Catalyst Sample: Powdered catalyst.

- Carrier Gas: High-purity inert gas (He, Ar, N₂).

- Probe Gas: A calibrated gas mixture (e.g., 5% CO in He, 10% H₂ in Ar) for pulse injection.

- Fixed-Bed Reactor: A U-shaped quartz or metal tube packed with the catalyst.

- Six-Port Injection Valve: Equipped with a calibrated sample loop for reproducible gas pulses.

- Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD): To measure the concentration of the probe gas in the effluent stream.

- Temperature-Controlled Furnace: To control the reactor temperature.

Procedure:

- Catalyst Pretreatment: a. Pack a known mass of catalyst into the fixed-bed reactor. b. Place the reactor in the furnace and connect it to the gas flow system. c. Activate the catalyst in-situ by heating under a flowing reducing or oxidizing gas stream. d. Cool the reactor to the analysis temperature (e.g., 40°C) under a pure inert carrier gas flow.

- Saturation via Pulse Chemisorption: a. Switch the injection valve to introduce a series of identical, small pulses of the probe gas into the carrier stream flowing over the catalyst. b. For each pulse, the TCD signal is recorded. The first few pulses will be completely adsorbed, showing no TCD response. c. As the catalyst surface becomes saturated, a portion of the probe gas passes through the reactor and is detected by the TCD. d. The process continues until the TCD peak area stabilizes, indicating no further adsorption (full saturation).

- Data Analysis: a. For each pulse, the quantity of gas adsorbed is the difference between the known injected amount and the amount detected by the TCD. b. The total chemisorbed gas capacity is the sum of the adsorbed quantities from all pulses before saturation. c. The metal dispersion and surface area are calculated from this total capacity, assuming an adsorption stoichiometry.

Advanced Application: Studying Competitive Adsorption

The presence of multiple gases in a reaction stream can significantly impact catalyst performance through competitive adsorption. A study on the hydrolysis of carbonyl sulfide (COS) over a MgAlCeOₓ catalyst provides an excellent example of how carrier gas methods and computational modeling can be combined to deconvolute these effects [33].

Experimental Insight:

- Under N₂ Atmosphere: COS conversion was high and stable. In situ IR spectroscopy showed that the dominant surface species were linear M–OH groups, which actively participated in the hydrolysis reaction [33].

- Under CO Atmosphere: COS conversion was significantly lower. In situ IR revealed a change in the distribution of surface hydroxyl groups, with a decrease in the active M–OH type. This was attributed to the competitive adsorption of CO molecules on the active sites, blocking them from reacting with COS [33].

DFT Calculations: Density Functional Theory calculations quantified this effect, showing that the adsorption energy of CO on the catalyst surface was higher (more negative) than that of COS (-34.39 kJ/mol vs. -18.27 kJ/mol), confirming that CO preferentially occupies the active sites in a CO-rich atmosphere [33].

Implication for Technique Selection: This case study underscores the importance of using realistic gas compositions during characterization. For catalysts intended for use in complex gas mixtures, the dynamic carrier gas method is uniquely suited for conducting competitive adsorption studies that more accurately predict in-service behavior, whereas static methods might overlook these critical interactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Gas Adsorption Experiments

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function / Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Gases | Selective chemisorption to quantify active sites. | H₂: For noble and group 8-10 metals (Pt, Pd, Ni). CO: For metals like Pt, Pd, Ru. O₂: For silver and base metals. NH₃/SO₂: For acid/base site characterization. |

| Inert Carrier/Diluent Gases | System purging, dead volume calibration, carrier stream. | Helium (He): Most common; high thermal conductivity. Argon (Ar), Nitrogen (N₂): Alternatives for specific detectors. Must be high purity (>99.995%). |

| High-Purity Nitric Acid | Preparation of calibration solutions and sample digestion. | Purified by double sub-boiling distillation (e.g., in PFA or quartz systems) to remove trace metal impurities [34]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Calibration and validation of analytical instruments and methods. | Monoelemental calibration solutions (e.g., Cd at 1 g/kg) with SI-traceable mass fractions, crucial for quantifying impurities in catalyst precursors [34]. |

| Supported Catalyst Samples | The material under investigation. | Active Phase: Metal (e.g., Pt, Ni). Support: High-surface-area material (e.g., Al₂O₃, SiO₂, TiO₂, Zeolites). Must be pre-treated (calcined/reduced) [19]. |

The strategic selection of a gas adsorption technique is fundamental to successful catalyst characterization. Volumetric analysis remains the gold standard for obtaining high-resolution physisorption and chemisorption isotherms for detailed textural and active site analysis. Gravimetric analysis offers the unique advantage of direct mass measurement and is ideal for coupling with thermal analysis. In contrast, the carrier gas method provides a fast, robust, and versatile platform for routine dispersion measurements and advanced temperature-programmed studies, especially in environments simulating realistic process conditions, including competitive adsorption.

There is no single "best" technique; the optimal choice is dictated by the specific research question, the required data quality, and available resources. A synergistic approach, often combining data from multiple techniques, provides the most comprehensive understanding of catalyst structure-property relationships, ultimately accelerating the development of more efficient and selective catalytic processes.

The characterization of solid catalysts via gas adsorption is a cornerstone of heterogeneous catalysis research, providing critical insights into parameters such as specific surface area, pore size distribution, and chemisorption properties. The accuracy and reproducibility of these measurements are fundamentally dependent on the initial steps of sample preparation and degassing, which ensure a clean, contaminant-free surface prior to analysis [35] [36]. This document outlines detailed application notes and protocols for these crucial procedures, framed within the context of catalyst characterization for research and development.

Theoretical Foundations of Degassing

The fundamental principle of degassing is to create an inert environment that exploits chemical potential, favoring the desorption of adsorbed molecules (e.g., water, CO₂) from the sample surface [35]. This process is driven by Le Chatelier’s principle; the concentration of adsorbed molecules on the surface is finite, while the concentration in the inert environment is near zero, shifting the equilibrium towards desorption [35]. The application of heat increases the rate of desorption, making temperature control a critical parameter [35].

Two primary degassing methods are employed:

- Vacuum Degassing: Relies on mass action, where the pressure is maintained near zero by evacuation. The driving force is the concentration gradient between the surface and the vapor phase [35].