Machine Learning Descriptors for Data-Driven Catalysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

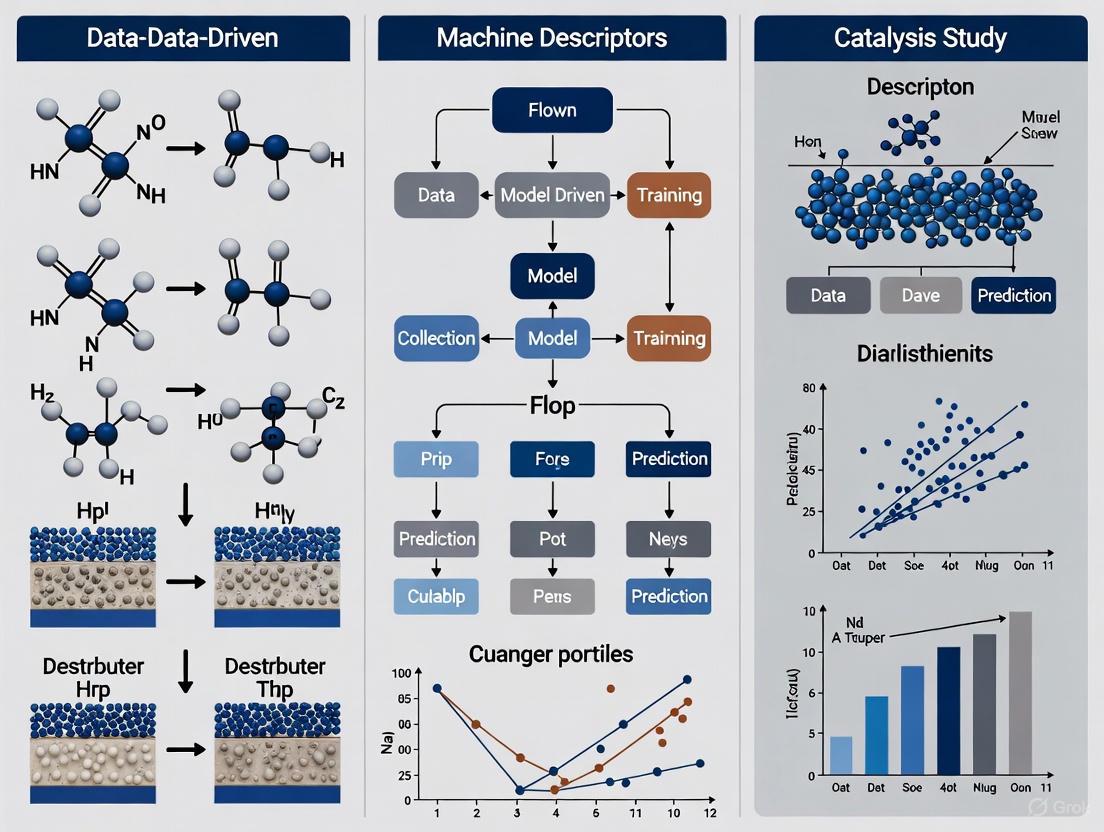

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of machine learning (ML) descriptors and their transformative role in accelerating catalysis research for drug development and chemical synthesis.

Machine Learning Descriptors for Data-Driven Catalysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of machine learning (ML) descriptors and their transformative role in accelerating catalysis research for drug development and chemical synthesis. It covers the foundational principles of catalytic descriptors, from basic definitions to their critical role in replacing traditional trial-and-error methods. The content details methodological approaches for descriptor selection and extraction across both experimental and computational domains, supported by real-world case studies in heterogeneous catalysis and electrocatalysis. Practical guidance addresses common challenges including data scarcity, model interpretability, and bridging the gap between computational predictions and experimental validation. By synthesizing insights from recent advances and comparative analyses, this guide equips researchers with the knowledge to implement effective ML-driven strategies for catalyst discovery and optimization, ultimately enabling more efficient therapeutic development.

Understanding Catalytic Descriptors: The Foundation of ML-Driven Discovery

Catalytic descriptors are quantitative or qualitative measures that capture key properties of a catalytic system, enabling the relationship between a material's structure and its function to be understood and predicted [1]. In the context of machine learning (ML) for data-driven catalysis studies, descriptors serve as the critical input features that allow algorithms to learn complex patterns and make accurate predictions about catalytic performance, dramatically accelerating the discovery and optimization of new materials [2] [3]. The evolution of these descriptors has progressed from early energy-based models to electronic descriptors and, most recently, to data-driven constructs capable of encapsulating multifaceted catalyst characteristics [1].

The selection and design of appropriate descriptors are decisive for the predictive accuracy of ML models and for uncovering the fundamental factors governing catalytic activity and selectivity [2] [3]. This document outlines the primary classes of catalytic descriptors, provides detailed protocols for their application—including a novel method for calculating adsorption energy distributions—and presents essential tools for researchers embarking on descriptor-driven catalyst design.

Categories of Catalytic Descriptors

Catalytic descriptors can be broadly classified into three categories based on their nature and the principles underlying their formulation. The following table summarizes their characteristics, advantages, and limitations.

Table 1: Categories of Catalytic Descriptors

| Descriptor Category | Key Examples | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Descriptors [1] | Adsorption energy (e.g., ΔGH, ΔGOH), Binding energies of reaction intermediates [1] | Relate catalytic activity to the Gibbs free energy or binding energy of reaction intermediates, guided by the Sabatier principle [1]. | Direct physical meaning; foundational for activity predictions via volcano plots [1]. | Computationally demanding; limited insight into electronic structure; constrained by scaling relationships [1]. |

| Electronic Descriptors [1] | d-band center, Density of States (DOS) [1] | Correlate electronic structure properties (e.g., d-band center position relative to Fermi level) with adsorption strength and catalytic activity [1]. | Provides insight into electronic origins of activity; improved computational efficiency [1]. | May not correlate well with all experimental factors; limited ability to capture subtle electronic effects in complex systems [1]. |

| Data-Driven & Structural Descriptors [4] [2] [3] | Adsorption Energy Distributions (AEDs) [4], Spectral descriptors [3], 3D voxel data [5] | Use ML or statistical methods to create descriptors from complex data, capturing structural and energetic heterogeneity. | Can represent complex, multi-facet systems; can integrate diverse data sources; powerful for ML prediction [4] [3]. | Dependency on data quality and quantity; potential "black box" nature; requires careful validation [2]. |

Protocol: Implementing Adsorption Energy Distributions (AEDs) for Catalyst Screening

The following protocol details the calculation and use of Adsorption Energy Distributions (AEDs), a novel data-driven descriptor designed to capture the activity of realistic nanocatalysts with multiple facets and binding sites, using the hydrogenation of CO₂ to methanol as a case study [4] [6].

Principle and Scope

The AED descriptor aggregates the binding energies of key reaction intermediates across different catalyst facets, binding sites, and adsorbates, forming a distribution that serves as a fingerprint of the catalyst's energetic landscape [4] [6]. This method is applicable to the screening of metallic and bimetallic catalysts for thermal heterogeneous reactions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Sources/Formats |

|---|---|---|

| Metallic Elements | Form the basis of the catalyst search space. | K, V, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Ga, Y, Ru, Rh, Pd, Ag, In, Ir, Pt, Au [4] [6]. |

| Key Adsorbates | Represent critical reaction intermediates for the target reaction. | *H, *OH, *OCHO (formate), *OCH₃ (methoxy) for CO₂ to methanol conversion [4] [6]. |

| Materials Project Database [4] [6] | Source for stable and experimentally observed crystal structures of metals and bimetallic alloys. | https://materialsproject.org/ |

| Open Catalyst Project (OCP) & fairchem [4] [6] | Provides pre-trained Machine-Learned Force Fields (MLFFs) and tools for rapid surface and adsorption energy calculations. | https://github.com/Open-Catalyst-Project/fairchem |

| Machine-Learned Force Field (MLFF) | Enables rapid and accurate computation of adsorption energies with a speed-up of ~10⁴ compared to DFT [4]. | OCP equiformer_V2 model [4]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Search Space Selection

- Identify a set of metallic elements relevant to the reaction of interest and available in the MLFF training database (e.g., OC20) to ensure prediction accuracy [4] [6].

- Query the Materials Project database to compile a list of stable bulk crystal structures for these elements and their bimetallic alloys [4] [6].

Surface Generation

Adsorbate Configuration Setup

- Engineer surface-adsorbate configurations for the selected key intermediates (e.g., *H, *OH, *OCHO, *OCH₃) on the most stable terminations of all generated facets [4] [6].

- Ensure multiple binding sites (e.g., top, bridge, hollow) are considered for each adsorbate on each facet to capture site-dependent energy variations.

Energy Calculation with MLFF

- Optimize all engineered surface-adsorbate configurations using a pre-trained MLFF (e.g., the OCP equiformer_V2 model) [4].

- Calculate the adsorption energy (Eads) for each configuration. The adsorption energy for an adsorbate *A is typically calculated as: Eads = Eslab+A - Eslab - EA, where Eslab+A is the energy of the slab with the adsorbate, Eslab is the energy of the clean slab, and EA is the energy of the isolated adsorbate molecule in the gas phase.

Data Validation and Cleaning

- Benchmarking: Select a subset of materials (e.g., Pt, Zn) and calculate a subset of adsorption energies using explicit DFT. Compare the results with MLFF predictions to establish a Mean Absolute Error (MAE), which should be within an acceptable range (e.g., ~0.16 eV) [4].

- Sampling: To ensure the computed AED is representative while managing resources, sample adsorption energies across the dataset, including the minimum, maximum, and median values for each material-adsorbate pair for validation [4].

Descriptor Construction and Analysis

- Construct AED: For each catalyst material, aggregate all calculated adsorption energies for the different adsorbates, facets, and sites into a probability distribution. This histogram or distribution is the AED descriptor [4].

- Compare Catalysts: Use unsupervised machine learning to analyze and compare AEDs. A robust method involves:

- Calculating the similarity between two AEDs using a metric like the Wasserstein distance (Earth Mover's Distance) [4] [6].

- Performing hierarchical clustering on the distance matrix to group catalysts with similar AED profiles [4] [6].

- Identifying promising new catalyst candidates by locating materials clustered near known high-performance catalysts.

Workflow Visualization

Machine Learning Integration and Advanced Techniques

The integration of catalytic descriptors with machine learning extends beyond screening into optimization and mechanistic elucidation. ML algorithms can be broadly divided into supervised and unsupervised learning, each with distinct applications in catalysis [7].

- Supervised Learning: Used for predicting continuous properties (regression) like yield or enantioselectivity, or categorical outcomes (classification). Common algorithms include:

- Unsupervised Learning: Used to find hidden patterns or groups in data without pre-defined labels, such as clustering catalysts by descriptor similarity [7]. This is instrumental in analyzing AEDs [4].

A powerful emerging paradigm involves using three-dimensional descriptors derived from transition-state structures. For chiral catalyst design, 3D image-like "voxel" descriptors derived from DFT-calculated transition-state structures have been used to train regression models that successfully predict enantioselectivity across multiple reaction types [5].

The journey from molecular features to machine-readable data is central to the success of data-driven catalysis. The strategic selection and construction of descriptors—from fundamental energy and electronic descriptors to advanced, data-intensive constructs like Adsorption Energy Distributions—provide the foundational language for machine learning models. The protocols and tools outlined herein offer a practical roadmap for researchers to implement these concepts, accelerating the rational design of next-generation catalysts. As the field evolves, the integration of large language models for data extraction [8] and more sophisticated multi-modal descriptors promises to further refine and automate the path from descriptor to discovery.

The Critical Role of Descriptors in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR)

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone computational approach in modern cheminformatics and drug discovery, mathematically linking a chemical compound's structure to its biological activity or properties [9]. These models operate on the fundamental principle that structural variations systematically influence biological activity, enabling the prediction of properties for new compounds without costly experimental testing [10]. The transformation of molecular structures into numerical representations, known as molecular descriptors, serves as the critical foundation for all QSAR modeling efforts [11] [9]. Descriptors quantitatively encode structural, physicochemical, and electronic properties of molecules, providing the predictor variables that machine learning algorithms use to establish patterns and relationships with biological responses [9].

The evolution of descriptor technology has progressed from simple one-dimensional properties to complex AI-driven representations [10]. In traditional QSAR, descriptors were primarily derived from known physicochemical principles or topological indices [12]. Contemporary approaches now leverage machine learning to generate data-driven descriptors that capture intricate structural patterns without manual engineering [11] [10]. This evolution has significantly expanded the applicability and predictive power of QSAR models across diverse domains, from catalytic materials design to toxicology prediction and drug discovery [13] [14] [2]. The strategic selection and appropriate application of molecular descriptors remains paramount for developing robust, interpretable QSAR models that can reliably guide scientific decision-making in research and development pipelines.

Classification and Types of Molecular Descriptors

Molecular descriptors can be categorized through multiple classification schemes based on their dimensionality, computational methodology, and the structural features they encode. The most fundamental classification organizes descriptors according to the level of structural information they incorporate, ranging from simple atomic counts to complex three-dimensional molecular representations.

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Descriptors by Dimensionality and Type

| Dimension | Descriptor Category | Key Examples | Representative Information Encoded |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D | Constitutional | Molecular weight, atom counts, bond counts | Basic compositional information |

| 2D | Topological | Connectivity indices, path counts, graph-theoretical descriptors | Molecular connectivity and branching patterns |

| 2D | Electronic | Partial charges, HOMO-LUMO energies, electronegativity | Electronic distribution and reactivity |

| 3D | Geometrical | Molecular surface area, volume, inertia moments | Three-dimensional shape characteristics |

| 3D | Quantum Chemical | HOMO-LUMO gap, dipole moment, electrostatic potential surfaces | Electronic properties derived from quantum calculations |

| 4D | Conformational | Ensemble-based properties, flexibility indices | Molecular flexibility and conformational diversity |

Beyond dimensionality-based classification, descriptors can be distinguished by their computational approach. Traditional descriptors include hand-crafted features based on known chemical principles, such as Crippen-Wildman partition coefficients (logP) for lipophilicity or Gasteiger partial charges for electronic properties [12]. These descriptors are typically interpretable and have clear chemical significance. Topological maximum cross correlation (TMACC) descriptors represent an advanced 2D approach that captures the maximum product of pairs of physicochemical properties for each topological distance in a molecule, providing alignment-independent representations suitable for QSAR modeling [12].

In contrast, modern AI-driven descriptors leverage deep learning to generate representations directly from molecular data. Graph neural networks (GNNs) create embeddings that capture both local and global molecular features without predefined rules [11]. Language model-based representations treat molecular strings (e.g., SMILES) as chemical language, using transformers to learn contextual relationships between atomic constituents [11]. These data-driven descriptors can capture complex, non-linear relationships that may be difficult to predefine with traditional approaches.

Calculation and Selection of Molecular Descriptors

The process of calculating molecular descriptors begins with accurate molecular representation and standardization. Chemical structures are typically represented using line notation systems such as SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) or more robust alternatives like SELFIES, which serve as input for descriptor calculation algorithms [11]. Prior to calculation, structures must undergo standardization procedures including removal of salts, normalization of tautomers, and handling of stereochemistry to ensure consistent descriptor values across the dataset [9].

Numerous software packages and libraries are available for descriptor calculation, each offering distinct advantages for specific applications. Open-source tools like RDKit and Mordred provide comprehensive descriptor sets with excellent integration into Python-based machine learning workflows, while proprietary solutions such as Dragon and ChemAxon offer extensively curated descriptor libraries with validated calculation methods [14] [9]. These tools can generate hundreds to thousands of descriptors for a given molecule, necessitating careful selection to avoid overfitting and maintain model interpretability.

Feature selection methods are crucial for identifying the most relevant molecular descriptors and improving model performance. Filter methods rank descriptors based on individual correlation or statistical significance with the target property using metrics like correlation coefficients or ANOVA [9]. Wrapper methods employ the modeling algorithm itself to evaluate different descriptor subsets through techniques such as genetic algorithms or simulated annealing [9]. Embedded methods perform feature selection during model training, as exemplified by LASSO regression, which automatically shrinks less important coefficients to zero, or random forests, which provide intrinsic feature importance measures [10] [9].

Table 2: Software Tools for Molecular Descriptor Calculation

| Software Tool | Descriptor Types | Access | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | 1D, 2D, 3D descriptors, fingerprints | Open-source | Python integration, comprehensive cheminformatics capabilities |

| Mordred | 1D, 2D, 3D descriptors (1826+ descriptors) | Open-source | High calculation speed, large descriptor library |

| Dragon | 1D, 2D, 3D descriptors (5000+ descriptors) | Commercial | Extensive validated descriptor database, GUI interface |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | 1D, 2D descriptors, fingerprints | Open-source | Standalone application, low memory requirements |

| ChemAxon | 1D, 2D descriptors, physicochemical properties | Commercial | Integration with other ChemAxon tools |

Advanced descriptor selection techniques include dynamic importance adjustment during model training, as implemented in modified counter-propagation artificial neural networks (CPANN) [15]. This approach allows different descriptor importance values for structurally different molecules, increasing model adaptability to diverse compound sets. For catalysis applications, descriptors often incorporate elemental properties such as period, group, atomic number, atomic radius, electronegativity, and surface energy, which have shown remarkable predictive power for properties like binding energies on bimetallic alloy surfaces [13].

Application Protocols: QSAR Modeling with Molecular Descriptors

Protocol 1: Traditional QSAR Modeling with Classical Descriptors

This protocol outlines the standard workflow for developing QSAR models using classical molecular descriptors and statistical learning approaches, suitable for datasets with well-defined mechanistic relationships.

Step 1: Dataset Curation and Preparation Collect a dataset of chemical structures with associated biological activities or properties from reliable sources. Ensure the dataset covers a diverse chemical space relevant to the problem domain. Standardize molecular structures by removing salts, normalizing tautomers, and handling stereochemistry consistently. Convert biological activities to a common unit (typically log-transformed values) and document experimental conditions and metadata [9].

Step 2: Descriptor Calculation and Preprocessing Calculate molecular descriptors using selected software tools (refer to Table 2 for options). For traditional QSAR, focus on interpretable descriptors such as topological indices, electronic parameters, and physicochemical properties. Preprocess descriptors by handling missing values (through removal or imputation) and scaling to zero mean and unit variance to ensure equal contribution during model training [9].

Step 3: Descriptor Selection and Model Building Apply feature selection methods to identify the most relevant descriptors. For initial modeling, consider filter methods based on correlation with the target property or embedded methods like LASSO regression. Split the dataset into training (∼70-80%), validation (∼10-15%), and external test (∼10-15%) sets, ensuring representative chemical space coverage in each split [9]. Build models using algorithms appropriate for the data characteristics: Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) for linear relationships, Partial Least Squares (PLS) for correlated descriptors, or Random Forests for non-linear patterns with maintained interpretability [10] [9].

Step 4: Model Validation and Interpretation Validate models using internal cross-validation (5-fold or 10-fold) and external test set evaluation. Calculate performance metrics including R² (coefficient of determination), Q² (cross-validated R²), and root mean square error (RMSE) for regression models, or accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score for classification models [9]. Interpret the model by examining descriptor coefficients and importance values, mapping significant descriptors back to chemical structures to identify key structural features influencing activity [12] [16].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Enhanced QSAR with Advanced Descriptors

This protocol describes the application of modern machine learning and deep learning approaches with advanced molecular representations for complex structure-activity relationships.

Step 1: Data Preparation and Modern Representation Curate and standardize the dataset as in Protocol 1. For deep learning approaches, consider using alternative molecular representations beyond traditional descriptors: SMILES strings for language model-based approaches, molecular graphs for GNNs, or precomputed molecular fingerprints as input for deep neural networks [11] [10]. For large datasets, consider deep learning approaches; for smaller datasets, prefer traditional machine learning with appropriate regularization.

Step 2: AI-Driven Descriptor Generation and Model Training Implement appropriate architectures for the selected representation: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for molecular graphs, Transformers for SMILES sequences, or Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs) for fingerprint inputs [11] [10]. Utilize modern frameworks such as DeepChem, PyTorch, or TensorFlow with cheminformatics extensions. For GNNs, configure graph convolutional layers to capture atomic environments and message-passing mechanisms to aggregate molecular information [16]. Employ transfer learning when possible by leveraging models pre-trained on large chemical databases.

Step 3: Model Interpretation using Advanced Techniques Apply model interpretation techniques to overcome the "black box" nature of complex ML models. For feature-based interpretation, use SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) to determine descriptor importance [10]. For structural interpretation, implement approaches like Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) for neural networks or Integrated Gradients for GNNs to visualize atomic contributions to predicted activity [16]. Validate interpretation reliability using benchmark datasets with predefined patterns where "ground truth" contributions are known [16].

Step 4: Model Deployment and Applicability Domain Assessment Deploy validated models for prediction on new compounds. Critically, define the applicability domain of the model to identify when predictions are reliable based on the chemical space of the training data [9]. Implement continuous validation procedures to monitor model performance over time and retrain with new data as necessary to maintain predictive accuracy.

QSAR Modeling Workflow: A Four-Phase Protocol

Case Study: Descriptor Applications in Catalysis Research

The application of QSAR principles and descriptor-based modeling extends significantly beyond traditional drug discovery into catalysis research, where descriptor-based machine learning approaches have demonstrated remarkable success in predicting catalytic properties and accelerating catalyst design.

In a seminal study on Cu-based bimetallic alloys for formic acid decomposition, researchers utilized readily available elemental properties as descriptors to predict CO and OH binding energies - key descriptors for catalyst performance [13]. The descriptor set included 18 distinct features for each metal in the alloy, including period, group, atomic number, atomic radius, atomic mass, boiling point, melting point, electronegativity, heat of fusion, ionization energy, density, and surface energy [13]. These descriptors were used to train multiple machine learning models, with the extreme gradient boosting regressor (xGBR) showing superior performance with root mean square errors of 0.091 eV and 0.196 eV for CO and OH binding energy predictions, respectively [13].

The predictive model demonstrated remarkable accuracy with mean absolute error of 0.02 to 0.03 eV compared to DFT-calculated values, while requiring negligible computational time compared to traditional quantum mechanical calculations [13]. The ML-predicted binding energies were subsequently used with ab initio microkinetic models to efficiently screen A3B-type bimetallic alloys for the formic acid decomposition reaction, showcasing a complete descriptor-driven workflow for catalyst design [13].

This case study illustrates several critical advantages of descriptor-based approaches in catalysis: (1) the use of easily accessible features from periodic tables and databases, avoiding costly computations; (2) physical interpretability of the descriptors, providing chemical insights into binding energy relationships; and (3) significant acceleration of the catalyst screening process through machine learning prediction of key parameters [13] [2].

Descriptor-Driven Catalyst Design Workflow

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Modeling

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation Software | RDKit, Mordred, PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon | Generate molecular descriptors from chemical structures | Fundamental to all QSAR workflows; converts structures to numerical features |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Scikit-learn, XGBoost, DeepChem, PyTorch | Implement ML algorithms for model building | Model development phase; provides algorithms for relationship learning |

| Model Interpretation Tools | SHAP, LIME, Integrated Gradients, Layer-wise Relevance Propagation | Explain model predictions and identify important features | Model interpretation phase; adds interpretability to "black box" models |

| Validation Frameworks | QSARINS, Build QSAR, Custom cross-validation scripts | Validate model performance and robustness | Model validation phase; ensures reliability and applicability domain definition |

| Specialized Descriptor Sets | TMACC descriptors, QuBiLS-MIDAS descriptors, Spectral descriptors | Address specific modeling challenges with tailored representations | Advanced QSAR; provides specialized representations for complex endpoints |

The effective application of QSAR modeling requires not only computational tools but also methodological frameworks for robust validation and interpretation. Cross-validation techniques including k-fold cross-validation and leave-one-out cross-validation provide internal validation of model performance [9]. External validation using completely independent test sets offers the most reliable assessment of predictive ability [9]. For interpretation, benchmark datasets with predefined patterns enable quantitative evaluation of interpretation approaches by comparing calculated contributions against known "ground truth" values [16].

Emerging approaches in QSAR modeling include causal inference frameworks that move beyond correlational analysis to identify descriptors with genuine causal effects on activity [17]. Double/debiased machine learning (DML) combined with false discovery rate control helps deconfound high-dimensional molecular features, providing more reliable and actionable insights for molecular design [17]. For catalysis applications, spectral descriptors and multi-modal learning approaches that combine computational and experimental data represent promising directions for enhancing predictive accuracy [2].

Molecular descriptors serve as the fundamental bridge between chemical structures and their biological activities or physicochemical properties in QSAR modeling. The strategic selection and appropriate application of descriptors—ranging from traditional interpretable features to modern AI-driven representations—determines the success of QSAR approaches across diverse domains from drug discovery to catalysis research [13] [2] [10]. The progression from classical statistical models to contemporary machine learning frameworks has significantly expanded the complexity of structure-activity relationships that can be captured, while simultaneously creating challenges in model interpretation that require advanced analytical approaches [11] [16].

The critical importance of rigorous validation and interpretability cannot be overstated, particularly as QSAR models increasingly inform decision-making in research and development pipelines [9] [16]. The development of benchmark datasets with predefined patterns provides essential resources for quantitatively evaluating interpretation methods and ensuring model reliability [16]. Furthermore, the emergence of causal inference approaches addresses the critical limitation of correlational models that may identify spurious relationships rather than genuine causal effects [17].

As molecular representation methods continue to evolve, integrating multi-modal data sources and leveraging advances in deep learning architectures, QSAR modeling is poised to expand its impact across chemical sciences [2] [11]. The integration of QSAR with complementary computational approaches such as molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations creates powerful workflows for understanding and optimizing molecular function [10]. Through continued methodological refinement and rigorous validation practices, descriptor-based QSAR modeling will remain an indispensable tool for accelerating the discovery and design of molecules with tailored properties and activities.

The design and optimization of catalysts have long been characterized by empirical, trial-and-error methodologies that are both time-consuming and resource-intensive. Traditional approaches rely heavily on chemical intuition and iterative experimentation, severely limiting the exploration of vast chemical spaces [18] [7]. The integration of machine learning (ML) represents a fundamental paradigm shift, introducing data-driven strategies that significantly accelerate discovery cycles and enhance mechanistic understanding [18]. This transformation marks a transition from intuition-driven and theory-driven phases to a new era characterized by the integration of data-driven models with physical principles [18]. In organometallic catalysis, where transition-metal-catalyzed reactions are pillars of modern synthesis, ML has emerged as an indispensable tool that complements both empirical and theoretical approaches by learning patterns from experimental or computed data to make accurate predictions about reaction yields, selectivity, optimal conditions, and mechanistic pathways [7].

ML Framework for Catalytic Research

Machine learning operates through a structured workflow that transforms raw data into predictive models and actionable insights. The foundation rests on two critical components: data representations and learning algorithms [7].

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The initial stage involves collecting and curating high-quality raw datasets from diverse sources including high-throughput experimentation, computational simulations, and scientific literature [18]. Data preprocessing includes standardization of molecular representations (SMILES, InChI, molecular graphs), duplicate removal, error correction, and normalization to ensure consistency [19] [20]. For catalytic systems, this phase often involves extracting or calculating molecular descriptors that encode electronic, steric, and structural properties relevant to catalytic performance [18].

Feature Engineering and Molecular Descriptors

Feature engineering transforms raw molecular data into quantifiable descriptors that serve as model inputs. Commonly used descriptors in catalysis research include:

- Physicochemical properties: oxidation states, coordination numbers, atomic radii

- Electronic parameters: HOMO/LUMO energies, d-band centers, Fukui indices

- Steric parameters: Tolman cone angles, steric maps, volume descriptors

- Structural features: bond lengths, angles, symmetry functions [18]

Advanced feature selection techniques like SISSO (Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) can identify optimal descriptors from thousands of candidates, establishing robust structure-property relationships [18].

Machine Learning Algorithms for Catalysis

ML algorithms are broadly categorized into supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning paradigms, each with distinct applications in catalytic research [18] [7].

Table 1: Key Machine Learning Algorithms in Catalysis Research

| Algorithm Category | Representative Methods | Catalysis Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Linear Regression, Random Forest, Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Support Vector Machines (SVMs) | Predicting catalytic activity, yield, selectivity; optimizing reaction conditions | High accuracy for predictive tasks; direct mapping from descriptors to properties |

| Unsupervised Learning | k-means clustering, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Identifying catalyst families; visualizing chemical space; pattern discovery in unlabeled data | Reveals hidden patterns without need for labeled data; hypothesis generation |

| Hybrid Methods | Semi-supervised learning, symbolic regression | Leveraging both labeled and unlabeled data; deriving interpretable mathematical expressions | Improved data efficiency; enhanced model interpretability |

Figure 1: Machine Learning Workflow in Catalysis Research

Application Protocols and Case Studies

Protocol: ML-Guided Optimization of Reaction Conditions

This protocol outlines the methodology for optimizing catalytic reaction conditions using supervised machine learning, adapted from case studies in organometallic catalysis [7].

Materials and Computational Methods:

- Data Collection: Compile historical experimental data including catalyst structures, substrates, temperatures, solvents, concentrations, and corresponding yields/selectivities

- Software Tools: Python with scikit-learn, RDKit for descriptor calculation, TensorFlow/PyTorch for neural networks

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute molecular descriptors for catalysts and substrates using RDKit or custom scripts

- Model Implementation: Train Random Forest or ANN models to map reaction parameters to outcomes

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Dataset Curation: Collect minimum of 50-100 historical experiments with varied conditions. Ensure balanced representation across parameter space.

- Feature Encoding: Convert categorical variables (e.g., solvent type, ligand class) using one-hot encoding. Standardize continuous variables.

- Model Training: Split data into training (70-80%), validation (10-15%), and test sets (10-15%). Implement cross-validation to prevent overfitting.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize critical parameters (e.g., number of trees in Random Forest, learning rate in neural networks) using grid search or Bayesian optimization.

- Prediction and Validation: Use trained model to predict optimal conditions. Validate top predictions experimentally.

- Iterative Refinement: Incorporate new experimental results to retrain and improve model accuracy.

In a representative application, this approach successfully identified optimal conditions for Pd-catalyzed cross-couplings with significantly reduced experimental effort compared to traditional optimization [7].

Protocol: Catalyst Screening via Machine Learning

This protocol describes a computational screening approach for identifying promising catalyst candidates from virtual libraries, minimizing synthetic effort.

Materials and Computational Methods:

- Virtual Libraries: Enumerate catalyst structures using combinatorial variation of ligand scaffolds and metal centers

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute electronic (DFT-calculated parameters) and steric descriptors (topological indices, volume parameters)

- Classification Models: Implement Support Vector Machines (SVMs) or Random Forest classifiers to predict high-performance catalysts

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Library Generation: Create virtual library of candidate catalysts using structural building blocks and reaction rules.

- Descriptor Calculation: Calculate comprehensive set of molecular descriptors for each candidate. DFT-level calculations may be required for electronic parameters.

- Model Application: Apply pre-trained classification model to predict catalytic performance. Models are typically trained on existing experimental data with similar reaction classes.

- Candidate Prioritization: Rank candidates by predicted performance and synthetic accessibility.

- Experimental Verification: Synthesize and test top-ranked candidates to validate predictions.

- Model Updating: Incorporate new experimental data to refine predictive models.

This methodology has been successfully applied to identify electrocatalysts for CO₂ reduction and oxidation catalysts for volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [21].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of ML Models in Catalysis Optimization

| Study Focus | ML Algorithm | Dataset Size | Prediction Accuracy | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cobalt-based VOC Oxidation [21] | Artificial Neural Networks (600 configurations) | Experimental data from 6 catalysts | High correlation (R² > 0.9) for conversion | Identified optimal catalyst matching commercial performance |

| Pd-catalyzed Allylation [7] | Multiple Linear Regression | 393 DFT-calculated reactions | R² = 0.93 for activation energies | Successfully captured electronic, steric, and hydrogen-bonding effects |

| Enantioselectivity Prediction [7] | Random Forest | 100s of asymmetric reactions | Accurate ee prediction for unseen substrates | Reduced optimization time by 60% compared to traditional approaches |

Protocol: Mechanistic Elucidation through Unsupervised Learning

This protocol employs unsupervised ML techniques to extract mechanistic insights from catalytic reaction data.

Materials and Computational Methods:

- Reaction Data: Collection of reaction progress data, spectroscopic measurements, or computational trajectories

- Dimensionality Reduction: Principal Component Analysis (PCA), t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE)

- Clustering Algorithms: k-means, hierarchical clustering, density-based clustering

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Compilation: Assemble multidimensional dataset (reaction rates, intermediate concentrations, spectroscopic features).

- Feature Standardization: Normalize features to comparable scales using z-score normalization.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply PCA to identify dominant patterns in the data and reduce dimensionality.

- Cluster Analysis: Implement clustering algorithms to group similar reaction profiles or catalyst behaviors.

- Pattern Interpretation: Correlate identified clusters with mechanistic hypotheses or catalyst characteristics.

- Model Refinement: Validate interpretations through targeted experiments or computational simulations.

This approach has revealed distinct mechanistic classes in complex catalytic networks and identified hidden structure-property relationships [18].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ML-Driven Catalysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | PubChem, ChEMBL, Cambridge Structural Database | Source of chemical structures and properties for training data |

| Cheminformatics Software | RDKit, Open Babel, PaDEL | Calculation of molecular descriptors and fingerprints |

| ML Frameworks | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Implementation of machine learning algorithms and neural networks |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Gaussian, ORCA, CP2K | Calculation of electronic structure descriptors for catalysts |

| Catalyst Libraries | Commercially available ligand sets, in-house catalyst collections | Experimental validation of ML predictions |

| High-Throughput Experimentation | Automated reactors, parallel synthesis systems | Rapid generation of training and validation data |

Visualization of Complex Relationships in Catalytic Systems

Figure 2: ML Modeling of Structure-Function Relationships in Catalysis

Machine learning has fundamentally transformed the landscape of catalytic research, enabling a systematic departure from traditional trial-and-error approaches. By bridging data-driven discovery with physical insight, ML establishes a new paradigm where predictive models guide rational design [18]. The integration of symbolic regression techniques, such as SISSO, further enhances interpretability by deriving mathematically explicit relationships between catalyst descriptors and performance metrics [18]. Emerging directions include the development of small-data algorithms for limited experimental datasets, standardized database infrastructures, and the synergistic potential of large language models (LLMs) for knowledge extraction from chemical literature [18]. As these methodologies mature, the continued fusion of physical principles with data-driven modeling promises to unlock unprecedented efficiencies in catalyst discovery and optimization, ultimately accelerating the development of sustainable chemical processes and novel therapeutic agents.

In the field of data-driven catalysis, descriptors are quantitative or qualitative measures that capture key properties of a system, enabling researchers to understand, predict, and optimize catalytic performance [1]. The integration of machine learning (ML) has transformed descriptor-based design, allowing for the navigation of vast chemical spaces that were previously inaccessible through traditional trial-and-error experimentation or computationally intensive quantum mechanical calculations [7] [22]. By establishing a mathematical relationship between a catalyst's fundamental features and its activity, selectivity, and stability, descriptors serve as the cornerstone for the rational design of novel catalytic materials [1] [2].

This article provides a structured overview of four key descriptor categories—Electronic, Structural, Compositional, and Spectral—framed within the context of ML-driven catalysis research. We summarize their defining characteristics, present quantitative data for comparison, and detail experimental and computational protocols for their application, offering a practical toolkit for researchers and scientists engaged in catalyst development.

Electronic Descriptors

Electronic descriptors quantify the electronic structure of catalytic materials, providing a bridge between a catalyst's intrinsic electronic properties and its adsorption behavior and reactivity [1] [23].

Key Electronic Descriptors and Applications

The d-band center theory, introduced by Jens Nørskov and Bjørk Hammer, is a foundational electronic descriptor for transition metal catalysts. It calculates the average energy of d-orbital levels relative to the Fermi level, which directly influences the adsorption strength of reactants on the metal surface [1]. A higher d-band center energy generally leads to stronger adsorbate bonding due to elevated anti-bonding state energies [1]. This descriptor is typically calculated using Density Functional Theory (DFT) by analyzing the density of states (DOS) for the d-orbitals, mathematically expressed as:

( \epsilond = \frac{\int E \rhod(E) dE}{\int \rho_d(E) dE} ) [1]

Another major category is energy descriptors, which are key tools for predicting active sites by analyzing the Gibbs free energy or binding energy of reaction intermediates [1]. For instance, the hydrogen adsorption energy (ΔGH) is a classic energy descriptor for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) [1]. A critical limitation addressed by modern ML approaches is the inherent "scaling relationship" between the adsorption energies of different intermediates, which can restrict catalytic efficiency [1]. Recent studies use ML to discover new, more complex electronic descriptors. For example, principal-component analysis (PCA) of the electronic density of states can identify accurate and interpretable descriptors that capture trends in chemisorption strength across metal alloys and oxides [23].

Protocol: Calculating the d-band Center Descriptor

- Objective: To determine the d-band center (εd) of a transition metal catalyst surface as a descriptor for adsorption energy prediction.

- Primary Instrument/Software: Density Functional Theory (DFT) code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO).

| Step | Task Description | Key Parameters & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Structure Optimization | Relax the bulk and surface structures until forces on atoms are < 0.01 eV/Å. Use a plane-wave cutoff energy of 500 eV and appropriate k-point mesh. |

| 2 | Electronic Structure Calculation | Perform a single-point energy calculation on the optimized structure to obtain the electronic density of states (DOS). |

| 3 | Projected DOS (PDOS) Analysis | Project the DOS onto the d-orbitals of the surface atoms of interest. This yields ρd(E), the d-band DOS. |

| 4 | d-band Center Calculation | Calculate εd using the formula above. The integration is typically performed over a relevant energy range (e.g., -10 eV to the Fermi level, EF). |

Structural and Compositional Descriptors

Structural descriptors capture the geometric arrangement of atoms at the catalytic site, while compositional descriptors describe the elemental identity and distribution within a material. The complexity of modern catalysts, such as high-entropy alloys (HEAs) and nanoparticles, demands sophisticated representations that can resolve subtle chemical-motif similarity [24].

Key Concepts and Recent Advances

Simple structural descriptors include coordination numbers (CNs) of surface atoms, which significantly improve the prediction of formation energies in adsorption motifs [24]. For instance, adding CNs as a local environment feature reduced the mean absolute error (MAE) in predicting metal-carbon bond formation energies from 0.346 eV to 0.186 eV in a random forest model [24].

To represent complex catalyst structures, graph-based representations are increasingly used. Atoms are treated as nodes and bonds as edges in a graph. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), particularly equivariant GNNs (equivGNNs), enhance these representations through message-passing between atoms, allowing the model to learn complex structure-property relationships [24]. One study developed an equivGNN model that achieved a remarkable mean absolute error (MAE) of <0.09 eV for predicting binding energies across diverse systems, including complex adsorbates on ordered surfaces, high-entropy alloys, and supported nanoparticles [24].

A novel structural-compositional descriptor is the Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED), which aggregates the binding energies of key reactants across different catalyst facets, binding sites, and adsorbates [4]. This descriptor captures the inherent complexity of nanostructured catalysts. In a study screening nearly 160 metallic alloys for CO2-to-methanol conversion, AEDs were used with unsupervised ML to identify promising candidates like ZnRh and ZnPt3 [4].

Protocol: Workflow for Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) Screening

- Objective: To generate and use Adsorption Energy Distributions (AEDs) for high-throughput computational screening of catalyst candidates.

- Primary Instrument/Software: Pre-trained Machine-Learned Force Fields (MLFFs) from projects like the Open Catalyst Project (OCP) [4].

Spectral Descriptors

Spectral descriptors are derived from spectroscopic techniques such as Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy. These descriptors contain rich information about molecular structure, bonding, and geometry, serving as a unique "fingerprint" for compounds [25] [26].

Applications in Data-Driven Catalysis

The primary application of spectral descriptors in ML is to infer molecular substructures and assemble molecular structures from spectroscopic data [25]. Traditional analysis relies on manual comparison with known databases, which is time-consuming. Machine learning models can accelerate this process by learning the complex mapping between spectral features and molecular geometry [26]. For example, one ML protocol uses Grad-CAM, a convolutional network interpretation technology, to determine crucial spectral features for retrieving precise molecular geometric information [26].

The scarcity of large, open-source spectral databases has been a limitation. To address this, researchers have used quantum chemical computations to generate extensive datasets. One such dataset provides computed Raman and IR spectra for approximately 220,000 molecules from the ChEMBL database, calculated at the PBEPBE/6-31 G level of theory using Gaussian09 [25]. This resource enables the training of ML models for tasks like predicting spectra for novel molecules or inferring structures from unseen spectra [25].

Protocol: Generating a Computational Spectral Dataset

- Objective: To construct a dataset of quantum-chemical Raman and IR spectra for machine learning tasks.

- Primary Instrument/Software: Gaussian09 software package [25].

| Step | Task Description | Key Parameters & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Molecule Selection | Extract molecular structures from a database (e.g., ChEMBL). Filter for drug-like molecules and reasonable size (e.g., 10-100 atoms) [25]. |

| 2 | Geometry Optimization | Perform a full geometry optimization of each molecule until its energy converges. Use a method like PBEPBE/6-31G for a balance of accuracy and efficiency [25]. Discard structures that fail to optimize. |

| 3 | Frequency Calculation | On the optimized geometry, run a frequency calculation. This yields harmonic frequencies, IR intensities, and Raman activities. |

| 4 | Data Extraction | Extract from the output: vibrational frequencies, IR intensities, Raman activities, reduced masses, force constants, and symmetry of vibration modes [25]. |

| 5 | Data Storage | Compile the data into a structured, accessible format (e.g., SQL database) for ML training [25]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and data resources essential for working with descriptors in data-driven catalysis research.

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function & Application in Descriptor Studies |

|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | The computational workhorse for calculating electronic (d-band center), energy (adsorption energies), and structural descriptors from first principles [1] [23]. |

| Gaussian09 Software | A leading quantum chemistry package used for computing molecular properties, including optimized geometries and vibrational spectra (Raman/IR) for spectral descriptor databases [25]. |

| Pre-trained ML Force Fields (MLFFs) | ML models trained on DFT data that predict energies and forces with near-DFT accuracy but at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling high-throughput descriptor generation (e.g., for AEDs) [4]. |

| Open Catalyst Project (OCP) Datasets | Provides large-scale datasets (e.g., OC20) and pre-trained MLFF models (e.g., Equiformer V2) specifically for catalyst systems, crucial for training and benchmarking models [4]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Models | A class of ML algorithms, such as equivariant GNNs, that naturally operate on graph representations of molecules and surfaces, automatically learning complex structural and compositional descriptors [24]. |

Bridging Computational and Experimental Data Through Intermediate Descriptors

In the field of data-driven catalysis, a significant challenge persists: the separation between computational design and experimental validation. Computational models, often trained on vast datasets generated from Density Functional Theory (DFT), excel at predicting atomic-scale properties like adsorption energies but frequently fail to perfectly predict real-world catalytic performance in reactors. Meanwhile, high-throughput experimentation (HTE) produces rich, empirical data on catalyst efficacy under realistic conditions, but this data can be difficult to interpret mechanistically. Intermediate descriptors serve as a critical bridge between these two worlds, transforming raw computational and experimental outputs into a shared language that machine learning (ML) models can use to accurately predict catalytic behavior and uncover fundamental structure-property relationships [3].

The selection of these descriptors is paramount. While the choice of ML algorithm is important, the definition of the descriptors themselves plays a decisive role in the predictive accuracy of the models [3]. Effective intermediate descriptors enable a novel research paradigm that combines large theoretical datasets with smaller, high-fidelity experimental sets, thereby accelerating the rational design of high-performance catalysts [3] [18]. This document outlines the core concepts, provides specific application notes, and details protocols for implementing this approach.

Core Concepts and Key Descriptor Types

Intermediate descriptors are representations of reaction conditions, catalysts, and reactants, extracted from original data to describe target properties in a machine-recognizable form [3]. They can be broadly categorized by their origin and application.

- Theory-Based Descriptors: Derived from computational simulations, these include atomic-scale properties such as adsorption energies, d-band centers, and energy barriers. A novel advanced descriptor is the Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED), which aggregates the binding energies for key reaction intermediates across different catalyst facets and binding sites. This descriptor captures the heterogeneity of real catalyst surfaces more effectively than single-facet calculations [4].

- Experiment-Based Descriptors: Sourced from experimental data, these include catalyst synthesis variables (e.g., precursor types, calcination temperature), operational conditions (e.g., temperature, pressure), and characteristics of the resulting material (e.g., surface area, porosity). The presence or absence of specific functional groups in catalyst additives can also be used as a descriptor [3].

- Spectroscopic Descriptors: These are a emerging class of descriptors derived from techniques like IR or NMR spectroscopy. They serve as powerful intermediate descriptors because they contain rich information about the chemical environment and bonding of intermediates on the catalyst surface, directly linking experimental observations with computational models [3].

Table 1: Categorization of Key Intermediate Descriptors in Catalysis Research

| Descriptor Category | Specific Examples | Data Origin | Target Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure | d-band center, Bader charges, Partial density of states | DFT Calculations | Adsorption energy, Catalytic activity |

| Energetic | Adsorption energy (single facet), Activation energy barrier | DFT Calculations | Reaction rate, Turn-over frequency |

| Morphological | Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) [4] | ML-Force Fields (MLFF) / DFT | Catalyst stability & activity across facets |

| Synthesis & Composition | Precursor identity, dopant concentration, functional group presence [3] | Experimental Recipe | Catalyst selectivity & yield |

| Operational | Reaction temperature, pressure, flow rate | Experimental Setup | Product Faradaic efficiency, Conversion |

| Spectroscopic | IR peak positions, NMR chemical shifts | Characterization Data | Surface intermediate identity, Bonding |

Application Notes

Case Study: Predictive Descriptor Development for CO₂ to Methanol

A recent study demonstrated a sophisticated workflow for discovering catalysts for CO₂ to methanol conversion using a novel intermediate descriptor [4]. The challenge was to move beyond single-facet descriptors limited to specific material families.

- Objective: To identify new, stable, and active bimetallic catalysts for thermocatalytic CO₂ reduction to methanol.

- Intermediate Descriptor: Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED). This descriptor was constructed by calculating the adsorption energies of key reaction intermediates (*H, *OH, *OCHO, *OCH₃) across numerous low-index facets and binding sites of nearly 160 metallic alloys [4].

- Workflow and Bridging Function:

- High-Throughput Computation: Machine-Learned Force Fields (MLFFs) were used to rapidly compute over 877,000 adsorption energies, a task infeasible with DFT alone [4].

- Descriptor Formation: The calculated energies for each material were compiled into a probability distribution—the AED—which serves as a fingerprint of the material's surface reactivity landscape.

- Unsupervised Learning & Validation: The similarity between AEDs of different materials was quantified using the Wasserstein distance metric. Hierarchical clustering was then used to group catalysts with similar AED profiles, allowing researchers to identify new candidate materials (e.g., ZnRh, ZnPt₃) based on their similarity to known effective catalysts [4].

This approach successfully bridged high-throughput computational screening with actionable catalyst design principles by using AED as a physically meaningful intermediate descriptor that encapsulates complex surface heterogeneity.

Case Study: Bridging Data in Electrocatalytic CO₂ Reduction

An experimental ML study on copper-based electrocatalysts for CO₂ reduction (CO₂RR) exemplifies the iterative use of descriptors to bridge catalyst recipe and performance [3].

- Objective: Determine the effect of a large library of metal and organic additives on the selectivity of Cu catalysts for producing CO, HCOOH, or C₂⁺ products.

- Intermediate Descriptors and Workflow: The study employed a three-round learning strategy with progressively refined descriptors [3]:

- Round 1 (Presence/Absence): Descriptors were simple one-hot vectors indicating the presence or absence of a specific metal or functional group in the catalyst recipe. This identified Sn and aliphatic OH groups as critical for CO and C₂⁺ selectivity, respectively.

- Round 2 (Molecular Fragments): Descriptors were advanced to "molecular fragment featurization" (MFF), representing the local structure of organic molecules. This refined the understanding, showing that nitrogen heteroaromatic rings favor CO, while aliphatic amino groups favor HCOOH.

- Round 3 (Feature Combinations): A "random intersection tree" algorithm was used to find synergistic combinations of features, revealing that aliphatic hydroxyl groups combined with amines enhance C₂⁺ yield.

- Bridging Function: This iterative protocol directly linked easily computable molecular features (descriptors) to complex experimental outcomes (Faradaic efficiency), creating a model that could predict the performance of newly designed molecules before synthesis [3].

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental and Computational Techniques

| Technique | Primary Function | Key Outputs | Role in Bridging Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [3] | Calculate electronic structure properties | Adsorption energies, Activation barriers, d-band center | Generates fundamental theory-based descriptors. |

| Machine-Learned Force Fields (MLFF) [4] | Accelerated atomic-scale simulations | Rapid relaxation of structures, Adsorption energies across facets | Enables high-throughput computation of complex descriptors like AED. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) [3] | Rapid, automated synthesis and testing | Catalytic activity/selectivity data across vast parameter spaces | Provides consistent, large-scale experimental data for model training. |

| Spectroscopy (e.g., IR, NMR) [3] [27] | Probe molecular structure and environment | Peak positions, intensities, chemical shifts | Provides experimental intermediate descriptors that reflect atomic-scale properties. |

Detailed Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Computational-Experimental Workflow Using AEDs

This protocol details the workflow for using Adsorption Energy Distributions (AEDs) to screen for new catalysts, as exemplified in the CO₂ to methanol case study [4].

I. Materials and Computational Resources

- Data Sources: Access to materials databases (e.g., Materials Project [4]).

- Software: DFT software (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO); MLFF frameworks (e.g., Open Catalyst Project (OCP) [4]); data analysis libraries (e.g., Pandas, NumPy in Python).

- Hardware: High-performance computing (HPC) cluster with CPUs and GPUs.

II. Procedure

- Search Space Definition:

- Identify a set of elements relevant to your catalytic reaction based on literature.

- Query materials databases for stable bulk crystal structures (e.g., single metals, bimetallic alloys) containing these elements.

- Perform bulk structure optimization using DFT to ensure stability.

Surface and Adsorbate Configuration:

- For each stable material, generate a set of low-index surface facets (e.g., Miller indices from -2 to 2).

- Identify the most stable surface termination for each facet.

- Engineer surface-adsorbate configurations for key reaction intermediates on these stable surfaces.

High-Throughput Energy Calculation:

- Use a pre-trained MLFF (e.g., OCP's Equiformer V2) to relax all surface-adsorbate configurations.

- Extract the adsorption energy for each configuration. The adsorption energy (E_ads) is calculated as:

E_ads = E_(surface+adsorbate) - E_surface - E_adsorbate_gas. - Validation: Benchmark MLFF-calculated adsorption energies against explicit DFT calculations for a subset of materials to ensure reliability (target MAE < 0.2 eV) [4].

Descriptor Construction (AED):

- For each material, compile all calculated adsorption energies for a specific adsorbate (e.g., *CO, *H) into a histogram or probability density function. This is the AED for that material/adsorbate pair.

- Repeat for all relevant adsorbates.

Data Analysis and Candidate Selection:

- Similarity Analysis: Treat AEDs as probability distributions. Calculate the pairwise similarity between all materials using a metric like the Wasserstein distance.

- Clustering: Perform hierarchical clustering on the distance matrix to group materials with similar AED fingerprints.

- Selection: Identify promising candidate materials that cluster with known high-performance catalysts but are themselves novel or unexplored.

III. Analysis and Interpretation The resulting clusters reveal materials with similar surface reactivity. Candidates in the same cluster as a top-performing catalyst are prioritized for experimental synthesis and testing. The AED provides a more comprehensive view of a catalyst's behavior under realistic conditions where multiple facets are exposed.

Protocol 2: An Iterative ML Approach for Experimental Optimization

This protocol outlines the iterative learning strategy for refining descriptors from experimental catalyst recipes, adapted from the CO₂RR study [3].

I. Materials

- Catalyst Library: A defined library of catalyst precursors and modifiers (e.g., metal salts, organic molecules).

- Testing Platform: A standardized experimental setup for high-throughput or rapid sequential testing of catalytic performance (e.g., electrochemical cell, microreactor).

- Data Analysis Tools: Machine learning environment (e.g., Python with scikit-learn, XGBoost).

II. Procedure

- Round 1: Primary Feature Identification

- Featurization: Encode catalyst recipes using one-hot encoding for the presence/absence of elements and broad functional groups.

- Modeling & Analysis: Train classification (e.g., Random Forest) and regression (e.g., Gradient Boosted Trees) models to predict catalytic performance. Perform feature importance analysis to identify the most influential elements and groups.

Round 2: Local Structure Elucidation

- Refined Featurization: For the critical components identified in Round 1, implement a more detailed featurization, such as Molecular Fragment Featurization (MFF), which captures the local chemical environment.

- Modeling & Analysis: Retrain ML models with the new descriptor set. This round should reveal more specific structural motifs (e.g., "aliphatic amine" vs. "aromatic amine") that drive selectivity.

Round 3: Synergistic Interaction Mapping

- Interaction Featurization: Use algorithms like Random Intersection Trees to search for combinations of features that have synergistic (positive or negative) effects on performance.

- Design & Prediction: Design new catalyst recipes based on the discovered important features and combinations. Use the trained model to vote on the predicted performance of these new designs.

- Validation: Synthesize and test the top-predicted candidates to validate the model's predictions and close the design-test-learn loop.

III. Analysis and Interpretation This iterative protocol progressively moves from coarse to fine descriptors, effectively building a quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) for catalytic performance. It directly translates human-readable chemical concepts into machine-learning-readable descriptors, enabling predictive design.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Open Catalyst Project (OCP) Models [4] | Pre-trained Machine-Learned Force Fields for accelerated adsorption energy calculations. | High-throughput screening of adsorption energies across multiple catalyst facets. |

| Metal Salt Additives (e.g., SnCl₂) [3] | Precursors for incorporating metal dopants or modifiers into a catalyst. | Tuning the selectivity of a copper catalyst in electrochemical CO₂ reduction. |

| Organic Molecules with Defined Functional Groups [3] | Additives that modify catalyst surface structure or electronic properties during synthesis. | Controlling catalyst morphology and product distribution in CO₂RR. |

| SISSO (Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) [18] | A compressed-sensing method for identifying the best low-dimensional descriptor from a vast pool of candidates. | Discovering complex, non-linear descriptors that link catalyst composition to activity. |

| High-Throughput Screening Reactor [3] | Automated instrumentation for rapid, parallel testing of catalyst performance under varied conditions. | Generating large, consistent datasets for training data-hungry ML models. |

Workflow Visualizations

Generalized Bridging Strategy

Iterative Descriptor Refinement Protocol

Descriptor Selection and Implementation Strategies in Catalysis Research

In the field of data-driven catalysis research, experimental descriptors are quantifiable parameters that provide a machine-readable representation of a catalytic system, encompassing the catalyst's properties, the conditions of its synthesis, and the parameters under which it operates [3]. The selection of appropriate descriptors is decisive for the predictive accuracy of Machine Learning (ML) models and for uncovering the key factors that influence catalytic activity and selectivity [3]. Moving beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches, a rigorous definition of these descriptors allows researchers to establish quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSARs) and navigate the vast, multidimensional space of catalytic reaction variables more efficiently [18] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagent categories and computational tools essential for extracting and utilizing experimental descriptors in ML-driven catalysis studies.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Descriptor-Driven Catalysis Research

| Category/Item | Specific Examples | Function & Relevance to Descriptors |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salt Additives | Sn, Pt, Pd salts [3] | Defines the active metal center; the metal identity is a primary descriptor for predicting selectivity in reactions like electrochemical CO₂ reduction [3]. |

| Organic Molecule Additives | Molecules with aliphatic OH, aliphatic amine, or nitrogen heteroaromatic rings [3] | Functional groups serve as key descriptors; their presence/absence significantly influences catalyst morphology and product selectivity [3]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Reactors | Automated catalyst testing systems [3] | Generates large, consistent datasets of catalytic performance under varied conditions, providing the essential data for training ML models on descriptor-activity relationships [3]. |

| Feature Extraction Software | Molecular Fragment Featurization (MFF) [3] | Transforms the molecular structure of organic additives into a numerical feature matrix, creating powerful descriptors for ML models [3]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Random Forest, XGBoost, Decision Tree [18] [3] [7] | Learns complex, non-linear relationships between experimental descriptors (inputs) and catalytic performance metrics like yield or selectivity (outputs) [7]. |

Categories and Data of Experimental Descriptors

Experimental descriptors can be systematically categorized to comprehensively describe a catalytic system. The quantitative values in the tables below serve as illustrative examples and reference points for the described categories.

Synthesis Condition Descriptors

These descriptors capture the variables involved in the catalyst preparation process, which ultimately determine the catalyst's final physical and chemical properties.

Table 2: Key Descriptors for Catalyst Synthesis Conditions

| Descriptor Category | Specific Examples | Representative Values / Data Types |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Composition | Presence/Absence of metal additives (e.g., Sn) [3] | Binary (Yes/No), Categorical (Metal Type) |

| Presence/Absence of functional organic groups (e.g., aliphatic -OH, -NH₂) [3] | Binary (Yes/No), Categorical (Group Type) | |

| Synthesis Procedure | Calcination temperature, precursor concentration, reduction time | Continuous (e.g., 500 °C) |

| Additive combination recipes (e.g., aliphatic OH + aliphatic carboxylic acid) [3] | Categorical, One-hot encoded vectors |

Operating Parameter Descriptors

These descriptors define the environment in which the catalytic reaction takes place.

Table 3: Key Descriptors for Reaction Operating Parameters

| Descriptor Category | Specific Examples | Representative Values / Data Types |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Conditions | Temperature, Pressure [3] | Continuous (e.g., 150 °C, 2 bar) |

| Reactant concentration, Solvent identity | Continuous, Categorical | |

| Reaction Type | Electrochemical CO₂ reduction [3] | Categorical |

| Oxidative dehydrogenation [3] | Categorical |

Catalyst Property Descriptors

These descriptors are the measurable properties of the synthesized catalyst material itself.

Table 4: Key Descriptors for Catalyst Properties

| Descriptor Category | Specific Examples | Representative Values / Data Types |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Properties | Surface area, Ionic radius [3] | Continuous (e.g., 150 m²/g) |

| Chemical Properties | Electronegativity, Standard heat of formation of oxides [3] | Continuous (Pauling units, kJ/mol) |

| Performance Metrics | Faradaic Efficiency (FE) for products (CO, HCOOH, C₂+) [3] | Continuous (Percentage) |

| Selectivity (e.g., for styrene, benzaldehyde) [3] | Continuous (Percentage) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Iterative Machine Learning for Catalyst Optimization

This protocol outlines a multi-round learning strategy to identify optimal catalyst recipes using descriptor analysis, as demonstrated for additive selection in copper-catalyzed electrochemical CO₂ reduction [3].

1. Primary Learning with One-Hot Encoded Descriptors

- Objective: Identify critical metal and functional group features.

- Procedure:

- Compile a library of potential additives (e.g., 12 metal salts, 200 organic molecules).

- Perform a representative subset of experiments from the possible combinations.

- Descriptor Extraction: Encode each catalyst recipe using one-hot vectors. Each vector indicates the presence (1) or absence (0) of a specific metal or functional group in the recipe [3].

- Model Training & Analysis: Train ML classification and regression models (e.g., Decision Tree, Random Forest) using the one-hot vectors as input to predict performance metrics (e.g., Faradaic efficiency). Perform descriptor importance analysis to identify the most critical features (e.g., Sn for CO selectivity, aliphatic -OH for C₂+ products) [3].

2. Secondary Learning with Molecular Fragment Descriptors

- Objective: Refine understanding of critical organic additives.

- Procedure:

- Descriptor Extraction: For the organic molecules flagged as important in Round 1, apply Molecular Fragment Featurization (MFF). This technique breaks down the molecular structure into a feature matrix representing local structural fragments [3].

- Model Training & Analysis: Train a new set of ML models using the MFF descriptor set. This analysis can reveal more nuanced structural requirements, such as the positive effect of aliphatic amine groups on HCOOH selectivity [3].

3. Tertiary Learning with Descriptor Interaction Analysis

- Objective: Discover synergistic or antagonistic effects between descriptor combinations.

- Procedure:

- Use algorithms like "random intersection tree" to screen for important combinations of the previously identified critical features [3].

- Validate predicted synergistic combinations (e.g., aliphatic hydroxyl group combined with aliphatic carboxylic acids enhances C₂+ yield) through targeted experiments [3].

Protocol: High-Throughput Experimentation for Data Generation

This protocol describes the use of high-throughput tools to generate the large, consistent datasets required for robust ML model training.

1. Automated Screening and Data Collection

- Objective: Generate a comprehensive dataset covering a wide parametric space.

- Procedure:

- Employ a high-throughput screening instrument that can automatically evaluate numerous catalysts (e.g., 20) under a wide array of reaction conditions (e.g., 216) [3].

- Ensure the instrument maintains well-defined, process-consistent conditions to minimize data variability.

- Collect data on catalytic performance (e.g., product composition) for thousands of individual data points (e.g., >12,000) [3].

2. Multi-Dimensional Descriptor Integration

- Objective: Create a unified dataset for model training.

- Procedure:

- For each data point, compile a vector of descriptors that encompasses both catalyst design information (e.g., composition, synthesis descriptor) and experimental process conditions (e.g., temperature, pressure) [3].

- This integrated descriptor set is vital for models to accurately predict performance and understand cooperative optimization of catalysts and processes.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated logical workflow of data generation, descriptor utilization, and model application in machine learning-driven catalysis research.

Diagram 1: ML-driven catalysis research workflow.

Computational descriptors are quantitative representations of a material's physical, chemical, or electronic properties that serve as input features for machine learning (ML) models in catalysis research. These descriptors bridge atomic-scale simulations with data-driven workflows, enabling the prediction of catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability without performing computationally expensive quantum mechanics calculations for every candidate material. By distilling complex electronic structures and atomic configurations into meaningful numerical values, descriptors facilitate high-throughput screening and rational catalyst design across diverse applications from renewable energy conversion to pharmaceutical development [28] [29].

The development of effective descriptors follows a fundamental principle: they must capture essential physicochemical properties governing catalytic behavior while being computationally efficient to calculate. Ideal descriptors balance transferability across material classes with specificity to the catalytic reaction of interest, providing both predictive power and mechanistic insight [24]. Recent advances in machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) and graph neural networks have further expanded the descriptor toolbox, allowing researchers to incorporate quantum-mechanical information into scalable models that accelerate catalyst discovery by orders of magnitude [4] [30].

Classification and Development of Computational Descriptors

Foundational Descriptor Categories

Computational descriptors for catalysis can be systematically classified into three foundational categories based on their origin and information content, each with distinct advantages and computational requirements [29].