Machine Learning for Catalyst Optimization and Outlier Detection: Advanced Strategies for Accelerated Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in catalyst optimization and data quality assurance through outlier detection for drug discovery and development professionals.

Machine Learning for Catalyst Optimization and Outlier Detection: Advanced Strategies for Accelerated Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in catalyst optimization and data quality assurance through outlier detection for drug discovery and development professionals. It covers foundational concepts of catalysts and outliers, details advanced ML methodologies like Graph Neural Networks and Isolation Forests, addresses critical challenges such as false positives and model scalability, and provides a comparative analysis of validation frameworks. By synthesizing the latest 2024-2025 research, this guide offers a comprehensive roadmap for leveraging ML to enhance research efficiency, data integrity, and decision-making in biomedical research.

Understanding the Core Concepts: Catalysts, Outliers, and Their Impact on Data Integrity

The Critical Role of Catalysts in Sustainable Energy and Drug Development

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Catalytic Activity in Electrochemical Reactions

Problem: Catalyst demonstrates lower than expected activity for oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) in metal-air batteries. Investigation & Solution:

- Check Electronic Descriptors: Calculate the catalyst's d-band center using DFT calculations. A d-band center too close to the Fermi level can cause overly strong intermediate binding, while one too far can cause weak binding; both reduce activity [1].

- Analyze Adsorption Energies: Use machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest) to predict the adsorption energies of key intermediates (O, C, N, H). Compare predictions with experimental results to identify discrepancies [1].

- Inspect for Outliers: Perform PCA on your catalyst dataset. Examine samples identified as outliers, as they may represent non-optimal synthesis conditions or impure phases that hinder activity. Use SHAP analysis to understand which features (e.g., d-band width, d-band filling) contribute most to outlier status [1].

Guide 2: Optimizing Dosage for Oncology Therapeutics (Project Optimus)

Problem: High rates of dose-limiting toxicities or required dose reductions in late-stage clinical trials for targeted therapies. Investigation & Solution:

- Re-evaluate FIH Trial Design: Move beyond the traditional 3+3 design. Employ model-informed drug development (MIDD) approaches that incorporate quantitative pharmacology and biomarker data (e.g., ctDNA levels) to select doses with a better benefit-risk profile [2].

- Implement Backfill Cohorts: In early-stage trials, use backfill cohorts to enroll more patients at dose levels below the maximum tolerated dose (MTD). This generates more robust safety and efficacy data for these potentially optimal doses [2].

- Utilize Clinical Utility Indices (CUI): Before pivotal trials, use a CUI framework to quantitatively integrate all available safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetic data from early studies to select the final dosage for confirmation [2].

Guide 3: Managing Inconsistent Results from ML-Based Catalyst Screening

Problem: Machine learning models for predicting catalyst performance yield inconsistent or unreliable results when applied to new data. Investigation & Solution:

- Audit Data Quality: Inconsistencies and lack of standardization in catalytic data are common challenges. Implement a robust, standardized data framework for feature collection (e.g., consistent calculation of d-band center, d-band width) [1].

- Validate Model on Outliers: Ensure your ML model can handle outliers. Use the dataset's outliers to test model robustness and refine the training set or model architecture to improve generalizability [1].

- Incorporate Generative AI: Use Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to explore uncharted material spaces and generate data for novel catalyst compositions, improving the model's predictive range and helping to identify promising, unconventional materials [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What electronic structure descriptors are most critical for predicting catalyst activity in energy applications? A: The d-band center is a foundational descriptor, as its position relative to the Fermi level governs adsorbate binding strength. Additional critical descriptors include d-band width, d-band filling, and the d-band upper edge. Machine learning models that incorporate these features can better capture complex, non-linear trends in adsorption energy [1].

Q: How can machine learning assist with outlier detection in catalyst research? A: After using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify outliers in a high-dimensional catalyst dataset, machine learning techniques like Random Forest (RF) and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis can be applied. These methods determine the feature importance, revealing which electronic or geometric properties (e.g., d-band filling) are most responsible for a sample's outlier status, providing insight for further investigation [1].

Q: Why is the traditional 3+3 dose escalation design inadequate for modern targeted cancer therapies? A: The 3+3 design was developed for cytotoxic chemotherapies and has key limitations [2]:

- It focuses only on short-term toxicity, not long-term efficacy.

- It does not align with the mechanism of action for targeted therapies and immunotherapies.

- It often fails to identify the true MTD and frequently leads to a recommended dose that is too high, resulting in subsequent dose reductions for nearly 50% of patients in late-stage trials [2].

Q: What are the key considerations for selecting doses for a first-in-human (FIH) oncology trial under Project Optimus? A: The focus should shift from purely animal-based weight scaling to approaches that incorporate mathematical modeling of factors like receptor occupancy differences between species. Furthermore, novel trial designs that utilize model-informed dose escalation/de-escalation based on efficacy and late-onset toxicities are encouraged to identify a range of potentially effective doses for further study [2].

Q: How can generative models like GANs be used in catalyst discovery? A: Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) can synthesize data to explore uncharted material spaces and model complex adsorbate-substrate interactions. They can generate novel, potential catalyst compositions by learning from existing data on electronic structures and chemisorption properties, significantly accelerating the material innovation process [1].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Machine Learning Workflow for Catalyst Optimization

Objective: To predict catalyst adsorption energies and identify optimal candidates using a machine learning framework. Methodology:

- Data Compilation: Assemble a dataset of heterogeneous catalysts with recorded adsorption energies for key species (e.g., C, O, N, H) and electronic structure descriptors (d-band center, d-band filling, d-band width, d-band upper edge) [1].

- Outlier Detection: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the dataset to identify outliers that may skew model training [1].

- Model Training & Validation: Train machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest, ANN) to predict adsorption energies from the electronic descriptors. Validate model accuracy against a held-out test set [1].

- Feature Importance Analysis: Use SHAP analysis on the trained model to determine which descriptors are most critical for predicting performance [1].

- Candidate Generation & Optimization: Employ a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to propose new catalyst compositions. Use Bayesian optimization to refine the selections towards desired properties [1].

Protocol 2: Model-Informed Dosage Optimization for Oncology Drugs

Objective: To determine an optimized dosage for a novel oncology therapeutic that maximizes efficacy and minimizes toxicity. Methodology:

- FIH Dose Selection: Use quantitative systems pharmacology models instead of allometric scaling alone to determine starting doses and the range for escalation, accounting for human-receptor biology [2].

- Dose Escalation: Implement a model-informed dose escalation design (e.g., Bayesian Logistic Regression Model) that incorporates real-time efficacy and toxicity data, rather than a strict 3+3 algorithm [2].

- Dose Expansion: Incorporate backfill cohorts at lower doses to enrich safety and efficacy data across the dose range. Use biomarkers (e.g., ctDNA) for early efficacy signals [2].

- Final Dose Selection: Prior to pivotal trials, use a Clinical Utility Index (CUI) to integrate all available data (safety, efficacy, PK/PD) and quantitatively select the final dosage for confirmation [2].

The tables below summarize key quantitative findings from the research.

| Descriptor | Definition | Impact on Adsorption Energy |

|---|---|---|

| d-band center | Average energy of d-electron states relative to Fermi level. | Primary descriptor; higher level = stronger binding. |

| d-band filling | Occupancy of the d-band electron states. | Critical for C, O, and N adsorption energies. |

| d-band width | The energy span of the d-band. | Affects reactivity; used in advanced ML models. |

| d-band upper edge | Position of the d-band's upper boundary. | Enhances predictive understanding of catalytic behavior. |

| Model Type | Application | Reported Performance / Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | Analyzing catalyst properties from synthesis/structural data. | Up to 94% prediction accuracy. |

| Decision Trees | Classification of catalyst properties. | Up to 100% classification performance. |

| Random Forest (RF) | Feature attribution and interpretability. | Enabled design of improved transition metal phosphides. |

| Metric | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Dose Reduction in Late-Stage Trials | ~50% of patients on small molecule targeted therapies. | Indicates initial dose is often too high. |

| FDA-Required Post-Marketing Dosage Studies | >50% of recently approved cancer drugs. | Confirms widespread suboptimal initial dosing. |

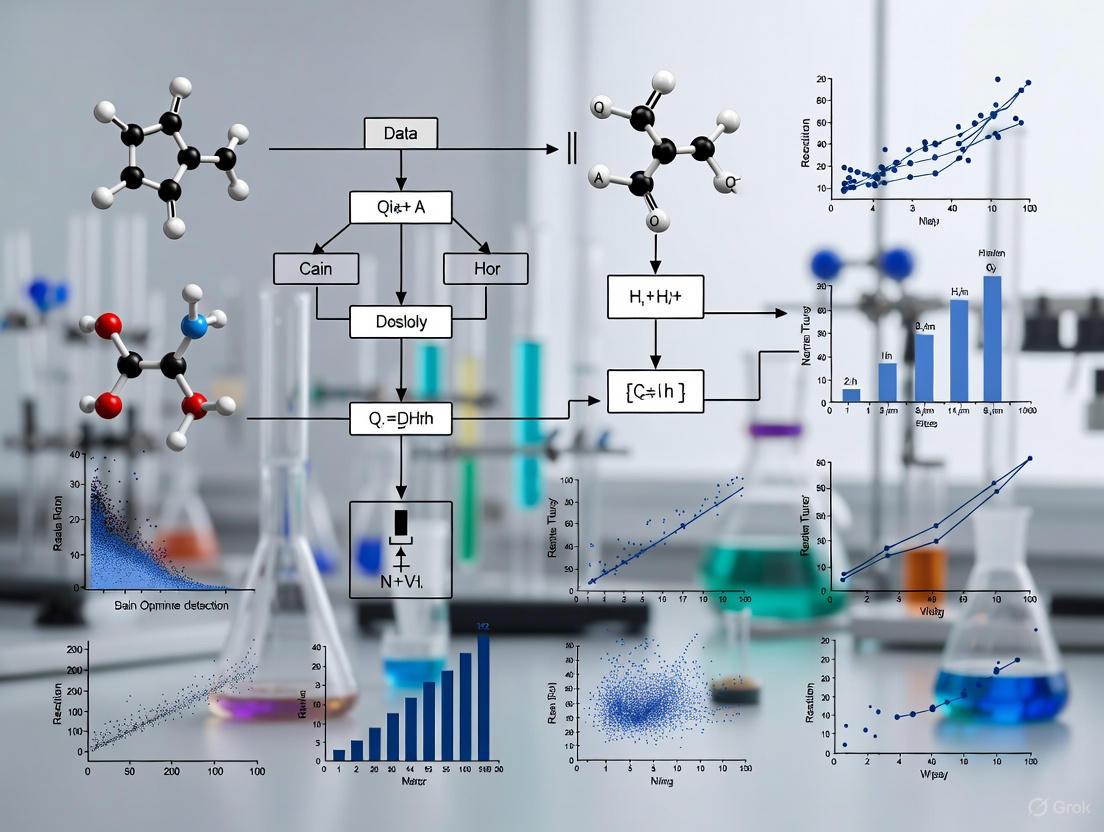

Workflow Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| d-band Descriptors | Fundamental electronic structure parameters (center, width, filling) used as inputs for ML models to predict catalyst chemisorption properties [1]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game-theoretic method used to interpret the output of ML models, explaining the contribution of each feature (descriptor) to a final prediction [1]. |

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) | A class of machine learning framework used for generative tasks; in catalysis, it can propose novel, valid catalyst compositions by learning from existing data [1]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | A statistical technique for emphasizing variation and identifying strong patterns and outliers in high-dimensional datasets, such as collections of catalyst properties [1]. |

| Clinical Utility Index (CUI) | A quantitative framework that integrates multiple data sources (efficacy, safety, PK) to support collaborative and objective decision-making for final dosage selection in drug development [2]. |

| Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) | An approach that uses pharmacological and biological knowledge and data through mathematical and statistical models to inform drug development and decision-making [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main types of outliers I might encounter in my catalyst research data? In machine learning for catalyst optimization, you will typically encounter three main types of outliers. Understanding these is crucial for accurate model training and interpretation [3] [4]:

- Point Anomalies (Global Outliers): A single data point that is extreme compared to the entire dataset.

- Contextual Anomalies (Conditional Outliers): A data point that is unusual within a specific context but might be normal otherwise.

- Collective Anomalies (Group Anomalies): A collection of related data points that, when observed together, are anomalous, even if each point seems normal individually.

Q2: Why is it critical to distinguish between these outlier types in catalyst design? Differentiating between outlier types allows for more precise root cause analysis [5]. A point anomaly in an adsorption energy value could indicate a data entry error, while a contextual anomaly might reveal a catalyst that performs exceptionally well only under specific reaction conditions (e.g., high pressure). A collective anomaly could signal a novel and valuable synergistic interaction in a bimetallic catalyst that would be missed by analyzing individual components alone [3] [1].

Q3: A point outlier is skewing my model's predictions. How should I handle it? First, investigate the root cause before deciding on an action [5]. The table below outlines a systematic protocol for troubleshooting point outliers.

| Investigation Step | Action | Example from Catalyst Research |

|---|---|---|

| Verify Data Fidelity | Check for errors in data entry, unit conversion, or sensor malfunction. | Confirm that an unusually high yield value wasn't caused by a misplaced decimal during data logging. |

| Confirm Experimental Context | Review lab notes for any unusual conditions during the experiment. | Determine if an outlier was measured during catalyst deactivation or an equipment calibration cycle. |

| Domain Knowledge Validation | Consult established scientific principles to assess physical plausibility. | Use density functional theory (DFT) calculations to check if an extreme adsorption energy is theoretically possible. |

| Action | Based on the investigation, either correct the error, remove the invalid data point, or retain it as a valid, though rare, discovery. |

Q4: I suspect a collective anomaly in my time-series catalyst performance data. How can I detect it? Collective anomalies are subtle and require specialized detection methods, as they are not obvious from individual points [3] [6]. The following workflow is recommended:

- Define the Collective Unit: Identify the data sequence, such as a series of yield measurements over consecutive experimental runs or a pattern across multiple descriptors (e.g., d-band center, d-band filling) [1].

- Apply Specialized Algorithms: Use machine learning models capable of detecting sequential patterns.

- Investigate the Mechanism: If a collective anomaly is detected, investigate the underlying cause, such as a gradual change in catalyst morphology or a synergistic effect between multiple reaction variables [1].

Q5: My model is either too sensitive to noise or misses real outliers. How can I fine-tune detection? Balancing sensitivity and specificity is a common challenge. Implement these best practices:

- Establish Meaningful Baselines: Understand the natural, contextual variation in your data. Account for expected seasonal patterns or known operational states in your high-throughput experimentation system [6].

- Use Ensemble Methods: Combine the results from multiple detection algorithms (e.g., Isolation Forest, Z-score, DBSCAN) to reduce false positives [6].

- Set Adaptive Thresholds: Instead of using fixed statistical thresholds, implement dynamic thresholds that learn from ongoing data, especially when dealing with non-stationary processes in catalyst testing [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving False Positives in Contextual Outlier Detection

Problem: Your detection system flags too many normal catalyst performances as contextual outliers, creating noise and wasting research time.

Solution: This is often caused by an inadequately defined "context." Follow these steps to refine your model:

- Audit Contextual Features: Review the features used to define context (e.g., reaction temperature, pressure, reactant concentration). Ensure they are the most relevant to the catalytic process. Use feature importance analysis (e.g., Random Forest or SHAP) to identify and retain only the most impactful features [1].

- Incorporate Domain Knowledge: Explicitly encode known high-level patterns. For example, if you know a catalyst's selectivity changes with pH, build this relationship into your model to prevent normal, context-dependent behavior from being flagged as anomalous.

- Adjust Sensitivity Settings: Increase the detection threshold slightly. For a Z-score-based method, you might move from 2 standard deviations to 2.5. For a machine learning model, adjust the classification probability threshold [6].

Guide 2: Diagnosing the Root Cause of a Confirmed Outlier

Problem: You have confirmed a genuine outlier in your dataset and need to diagnose its origin to guide your research.

Solution: Systematically categorize the outlier's root cause to determine the next steps [5].

Root Cause Diagnosis Workflow

- If the root cause is

ErrororFault: Focus on correcting your experimental protocol, cleaning the data, or repairing equipment. This is a data quality issue. - If the root cause is

Natural Deviation: You can typically retain the data point but may choose to weight it differently in your models. - If the root cause is

Novelty: This represents a potential discovery. Prioritize further investigation and replication of the conditions that led to this outlier, as it may reveal a new catalyst behavior or optimization pathway [5].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: A Methodology for Systematic Outlier Analysis in Catalyst Datasets

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for integrating outlier analysis into a catalyst discovery pipeline, leveraging insights from recent ML-driven research [1].

Outlier Analysis Experimental Protocol

1. Data Compilation & Feature Engineering:

- Compile a dataset of catalyst properties and performance metrics (e.g., adsorption energies for C, O, N, H) [1].

- Calculate key electronic-structure descriptors, such as the d-band center, d-band filling, d-band width, and d-band upper edge relative to the Fermi level. These are critical features for understanding catalytic activity [1].

- Extract structural and compositional features from catalyst formulations.

2. Dimensionality Reduction:

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize the overall dataset structure and identify global outliers that lie outside the main data clusters [1].

- Use t-SNE or UMAP to explore the chemical space of catalysts and reactions, which helps in assessing domain applicability and identifying collective anomalies [1] [7].

3. Multi-Method Outlier Detection: Apply a suite of detection methods to capture different anomaly types. The table below summarizes quantitative results from a benchmark study on a catalyst dataset [1].

| Detection Method | Anomaly Type Detected | Key Performance Metric | Note on Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCA-based Distance | Global, Collective | Effective for initial clustering and finding points far from the data centroid [1]. | Fast, good for first-pass analysis. |

| Isolation Forest | Point | High precision in identifying isolated points [6]. | Efficient for high-dimensional data. |

| K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | Contextual, Point | ROC-AUC: 0.94 (in a medical imaging case study) [7]. | Distance to neighbors provides a useful anomaly score. |

| SHAP Analysis | All Types (Diagnostic) | Identifies d-band filling as most critical feature for C, O, N adsorption energies [1]. | Not a detector itself, but explains which features caused a point to be an outlier. |

4. Root Cause Analysis with SHAP:

- Use SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) on your trained predictive models to determine the feature-level contribution to an outlier observation [1].

- For example, if a catalyst is an outlier due to high predicted activity, SHAP can reveal whether this is driven by an unusual d-band center or another electronic descriptor. This transforms an outlier from a statistical curiosity into a mechanistic insight.

5. Hypothesis Generation & Validation:

- Formulate a scientific hypothesis based on the root cause. For example, "Catalysts with a d-band upper edge below -2.0 eV show anomalously high selectivity."

- Design targeted experiments or higher-fidelity computational studies (e.g., DFT calculations) to validate this hypothesis, closing the loop between data analysis and scientific discovery [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational and data components essential for implementing the outlier analysis framework described in this guide.

| Item / Reagent | Function in Outlier Analysis | Example in Catalyst Research |

|---|---|---|

| d-band Descriptors | Electronic structure features that serve as primary inputs for predicting adsorption energies and identifying anomalous catalytic behavior [1]. | d-band center, d-band filling, d-band width. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game-theoretic method for explaining the output of any machine learning model, crucial for diagnosing the root cause of outliers [1]. | Explains whether an outlier's high predicted yield is due to its d-band center or another feature. |

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) | A generative model used to explore unch regions of catalyst chemical space and create synthetic data for improved model training [1]. | Generates novel, valid catalyst structures for testing hypotheses derived from outlier analysis. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | A dimensionality reduction technique used to visualize high-dimensional data and identify global outliers that fall outside main clusters [1]. | Projects a dataset of 235 unique catalysts into 2D space to reveal underlying patterns and anomalies [1]. |

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | A generative model used for inverse design, creating new catalyst structures conditioned on desired reaction outcomes and properties [8]. | Generates potential catalyst molecules given specific reaction conditions as input. |

How Outliers Skew Results and Jeopardize Data Integrity in Clinical Datasets

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the practical consequences of outliers in clinical data analysis? Outliers can significantly degrade the performance of analytical models. In bioassays, for example, a single outlier in a test sample can increase measurement error and widen confidence intervals, reducing both the accuracy and precision of critical results like relative potency estimates [9].

Q2: Should outliers always be removed from a dataset? No, not always. The decision depends on the outlier's root cause [5]. Outliers stemming from data entry errors or equipment faults are often candidates for removal. However, outliers that represent rare but real biological variation or novel phenomena can contain valuable information and should be retained and investigated, as they may lead to new clinical discoveries [5] [10].

Q3: What is the difference between an outlier and an anomaly? In many contexts, the terms are used interchangeably [5]. However, a nuanced distinction is that an "anomaly" often implies a deviation with real-life relevance, whereas an "outlier" is a broader statistical term. Some definitions specify that an outlier is an observation that deviates so much from others that it seems to have been generated by a different mechanism [5].

Q4: How can AI help in managing outliers in clinical trials? AI and machine learning can rapidly analyze vast clinical trial datasets to identify patterns, trends, and anomalies that might be missed by manual review [11]. They can flag potential correlations between datasets and predict risks, such as adverse patient events. It is crucial to note that AI acts as a tool to guide clinical experts, not replace their subject matter expertise [11].

Q5: What are some common methods for detecting outliers? Several statistical and computational methods are commonly used, each with its strengths. The table below summarizes key techniques [12] [10].

Table: Common Outlier Detection Methods

| Method | Principle | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Z-Score | Measures how many standard deviations a point is from the mean. | Data that is normally distributed [12]. |

| IQR (Interquartile Range) | Defines outliers as points below Q1 - 1.5xIQR or above Q3 + 1.5xIQR. | Non-normal distributions; uses medians and quartiles for a robust measure [12] [10]. |

| Modified Z-Score | Uses median and Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) instead of mean and standard deviation. | When the data contains extreme values that would skew the mean and SD [12]. |

| Local Outlier Factor (LOF) | A density-based algorithm that identifies outliers relative to their local neighborhood. | Identifying local outliers in non-uniform data where global methods fail [12] [10]. |

| Isolation Forest | A tree-based algorithm that isolates outliers, which are easier to separate from the rest of the data. | Efficient for high-dimensional datasets [10]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: A Step-by-Step Protocol for Outlier Management

Managing outliers is a critical step to ensure data integrity. The following workflow provides a systematic approach.

1. Detection: Choose a method appropriate for your data. For a quick initial view, use visualizations like box plots or scatter plots [12]. For high-dimensional data, such as transcriptomics from microarrays or RNA-Seq, employ specialized methods like bagplots or PCA-Grid after dimension reduction [13].

2. Investigation: Determine the root cause for each potential outlier [5]. Consult with lab technicians about potential measurement errors and clinical partners about patient-specific factors. This step is vital to avoid removing valid biological signals.

3. Strategy Decision & Implementation: Based on the investigation, choose and execute a management strategy:

- Include: If the outlier represents a rare but real case (e.g., a novel side effect), retain it. In some cases, you might increase the weight of these instances in machine learning models to improve their predictive capability for abnormal samples [14].

- Remove: If the outlier is conclusively traced to an error (e.g., instrument malfunction or protocol violation), removal is appropriate [12] [10] [15].

- Transform: Apply mathematical transformations (e.g., log transformation) to reduce the impact of extreme values without removing them [12].

4. Analysis: Proceed with your primary data analysis. For classifier development in transcriptomics, it is considered best practice to report model performance both with and without outliers to understand their impact fully [13].

5. Documentation: Meticulously record the outliers detected, the methods used, the investigated root causes, and the final actions taken. This ensures the process is transparent, defensible, and reproducible [9].

Guide 2: Impact on Machine Learning Classifiers

Outliers in training or test data can drastically alter the estimated performance of machine learning classifiers, making them unreliable for clinical use [13]. The following workflow is recommended for robust classifier evaluation.

Objective: To assess the stability and real-world applicability of a classifier by evaluating its performance across different outlier scenarios.

Protocol:

- Assess Outlier Probability: Use a bootstrap procedure to resample your dataset multiple times. For each resampled set, identify outliers using a method like a bagplot on principal components. The outlier probability for each sample is the frequency with which it is flagged as an outlier across all bootstrap runs [13].

- Evaluate Classifier Performance: Train and validate your classifier (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) under three distinct conditions [13]:

- Scenario A: Using all available samples.

- Scenario B: After removing simulated or known technical outliers.

- Scenario C: After removing samples with a high outlier probability (e.g., >70%).

- Compare Results: Analyze performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, Brier score) across the three scenarios. A significant performance shift indicates that your classifier is highly sensitive to outliers, and its reported performance may not be reproducible on independent data [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Reagents & Solutions for Outlier Management Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| R/Python with Statistical Libraries (e.g., scikit-learn, statsmodels) | Provides the core computational environment for implementing detection methods like Z-Score, IQR, and Local Outlier Factor (LOF) [12]. |

| Visualization Tools (e.g., matplotlib, seaborn) | Essential for creating box plots, scatter plots, and other visualizations for the initial identification and presentation of outliers [12]. |

| PCA & Robust PCA Algorithms | A key technique for dimension reduction, allowing for the visualization and detection of sample outliers in high-dimensional data like gene expression profiles [13]. |

| Pre-trained AI Models (e.g., for clinical data review) | Accelerate the process of identifying data patterns, trends, and anomalies in large clinical trial datasets, flagging potential issues for expert review [11]. |

| Bootstrap Resampling Methods | Used to estimate the probability of a sample being an outlier, providing a quantitative measure to guide removal decisions in classifier evaluation [13]. |

Troubleshooting Guides for HEA Catalyst Research

Phase Purity and Synthesis Issues

Problem: Failure to achieve a single-phase solid solution during HEA synthesis. Question: After using carbothermal shock synthesis, my HEA nanoparticles show phase segregation under SEM. What could be causing this?

Diagnosis & Solution: This typically indicates that the thermodynamic parameters for stabilizing a solid solution were not met.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Calculate the mixing entropy (ΔS_mix) of your target composition. A value exceeding 1.6R (where R is the gas constant) is characteristic of HEAs [16].

- Calculate the enthalpy of mixing (ΔH_mix) for all elemental pairs in your composition. Highly positive values lead to segregation, while strongly negative values promote intermetallic formation [17] [16].

- Use the

Gibbs free energy criterion: ΔGmix = ΔHmix - TΔSmix. A negative ΔGmix favors solid solution formation. Ensure your synthesis temperature (T) is sufficiently high to overcome a positive ΔH_mix [17].

Solution Protocol:

- Composition Adjustment: Use Hume-Rothery-like guidelines for HEAs. Select elements with similar atomic radii (atomic size difference < ~6.5%) and similar crystal structures to reduce lattice strain [17].

- Synthesis Optimization: For carbothermal shock synthesis, ensure:

- Rapid Quenching: The cooling rate must be high enough to prevent elemental diffusion and phase separation. Verify with the robotic platform that the cooling profile is consistent and sufficiently fast [18].

- Precursor Homogeneity: The robotic liquid handler must create a perfectly homogeneous metal precursor mixture before the shock process [18].

Adsorption Energy Prediction and Site Variability

Problem: Large variability and unreliable predictions for adsorption energies on HEA surfaces from ML models. Question: My graph neural network model predicts adsorption energies for formate oxidation on a Pd-Pt-Cu-Au-Ir HEA with high variance. How can I improve model confidence?

Diagnosis & Solution: This is a classic symptom of the "compositional complexity" of HEAs, where a single composition can have millions of unique surface adsorption sites [19].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Uncertainty Quantification (UQ): Implement UQ methods to detect outliers in your model's predictions. Ensemble methods (using multiple independently trained models) have been shown to provide ~90% detection quality for structures with large errors, outperforming single-network methods [20].

- Feature Analysis: Ensure your model's feature vector adequately describes the complex local environment of each adsorption site, including the identity and geometry of nearest-neighbor atoms [19].

Solution Protocol:

- Adopt a Direct Prediction Strategy: For rapid screening, use an ML model that performs "direct" prediction of adsorption energies from unrelaxed surface structures, leveraging handcrafted features or graph representations [19].

- Implement an Iterative Workflow: For higher accuracy, use an "iterative" strategy where an ML-based potential energy surface (PES) guides the relaxation of the surface structure before energy prediction. This is more computationally intensive but more accurate for novel configurations [19].

- Active Learning Loop: Integrate your model with a Bayesian optimization (BO) active learning loop. The BO algorithm should propose new compositions or sites for DFT calculation based on the model's uncertainty, systematically improving the training set in underrepresented regions of the design space [18] [19].

AI-Guided Optimization and Outlier Detection

Problem: An AI agent exploring the multimetallic catalyst space gets stuck in a local performance minimum. Question: The CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists) AI system in my lab is no longer suggesting catalyst compositions that improve performance. What is happening?

Diagnosis & Solution: This is often due to a poor exploration-exploitation balance in the active learning algorithm or a failure to properly account for "out-of-distribution" (OOD) samples.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Check the Acquisition Function: Review the Bayesian Optimization setup. The acquisition function (e.g., Knowledge Gradient) must dynamically balance exploring new regions of the parameter space and exploiting known high-performing regions [18].

- Analyze for Distribution Shift: Use an OOD detection method to see if the AI is suggesting compositions that are too dissimilar from its training data, leading to unreliable predictions [18].

Solution Protocol:

- Multimodal Data Integration: Enhance the AI agent with multimodal data. The CRESt system, for example, uses Large Vision-Language Models (LVLMs) to incorporate prior literature knowledge and real-time characterization images (from SEM) into the search space, providing a richer context for decision-making [18].

- Lagrangian Multiplier: Implement an adaptive exploration-exploitation trade-off. The CRESt system uses a Lagrangian multiplier, inspired by reinforcement learning, to dynamically adjust this balance without manual tuning [18].

- Robotic Self-Diagnosis: Utilize the robotic platform's cameras and LVLMs to monitor experiments for subtle deviations (e.g., precursor deposition errors) and suggest corrections, ensuring data quality and reproducibility [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What defines a "high-entropy" alloy, and why is it relevant for catalysis? A1: High-entropy alloys are traditionally defined as solid solutions of five or more principal elements, each in concentrations between 5 and 35 atomic percent [17] [19]. The high configurational entropy from the random mixture of elements can stabilize simple solid solution phases (FCC, BCC) [17]. For catalysis, this randomness creates a vast ensemble of surface sites with unique local environments, leading to a quasi-continuous distribution of adsorption energies for reaction intermediates. This diversity increases the probability of finding sites with near-optimal binding energy, potentially surpassing the performance of traditional catalysts [18] [19].

Q2: What are the "four core effects" in HEAs, and how do they impact catalytic properties? A2: The four core effects are foundational to HEA behavior [17]:

- High Entropy Effect: Promotes the formation of simple solid solutions over complex intermetallic compounds.

- Severe Lattice Distortion: Atomic size differences cause significant strain, which can modify electronic structure and surface reactivity.

- Sluggish Diffusion: Atomic diffusion is slow due to an irregular potential energy landscape, enhancing thermal stability.

- Cocktail Effect: The synergistic interaction of multiple elements leads to properties that are not simply an average of the constituents. In catalysis, this directly enables the tuning of surface interactions [17].

Q3: My ML model for HEA property prediction performs well on the test set but fails on new, unseen compositions. Why? A3: This is a classic case of model degradation under distribution shift [18]. Your test set likely comes from the same distribution as your training data, but your new compositions are "out-of-distribution" (OOD). To address this:

- Use Uncertainty Quantification: Employ ensemble models, which are highly effective at detecting OOD samples by assigning high uncertainty to them [20].

- Incorporate OOD-aware evaluation: Actively use your model's UQ to identify and prioritize these uncertain samples for further DFT calculation or experimentation, gradually expanding the model's robustness [18] [19].

Q4: What robotic and automated systems are available for high-throughput HEA discovery? A4: The field is moving towards integrated "self-driving laboratories." Key components include:

- Robotic Platforms: Systems like the AMDEE (AI-Driven Integrated and Automated Materials Design for Extreme Environments) project feature closed-loop automation for sample fabrication, characterization (XRD, nanoindentation), and dynamic testing [21].

- AI Orchestration: Platforms like CRESt combine robotic liquid handling, carbothermal shock synthesis, automated microscopy, and electrochemistry, all orchestrated by an agentic AI that uses LVLMs and Bayesian optimization [18].

- Open-Source Software: Frameworks like ChemOS and AlabOS provide orchestrating architecture for building and managing such autonomous experiments [18].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Superconducting Properties of Selected High-Entropy Alloys

| HEA Composition | Crystal Structure | Critical Temperature (T_c) | Critical Field (H_c) | Electron-Phonon Coupling Constant (λ) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ta₃₄Nb₃₃Hf₈Zr₁₄Ti₁₁ | BCC | 7.3 K | - | 0.98 - 1.16 | [16] |

| (ScZrNb)₀.₆₅(RhPd)₀.₃₅ | CsCl-type | 9.3 K | - | - | [16] |

| Nb₃Sn (Reference) | A15 | 18.3 K | 30 T | - | [16] |

Table 2: Comparison of Uncertainty Quantification Methods for ML Potentials

| UQ Method | Principle | Computational Cost | Outlier Detection Quality* | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ensembles | Multiple independent models | High | ~90% | Highest accuracy; reactive PES |

| Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) | Statistical clustering | Medium | ~50% | Near-equilibrium PES |

| Deep Evidential Regression (DER) | Single-network variance prediction | Low | Lower than Ensembles | Fast, less complex systems |

*Detection quality when seeking 25 structures with large errors from a pool of 1000 high-uncertainty structures [20].

Essential Experimental Workflows & Signaling Pathways

AI-Driven HEA Catalyst Discovery Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the closed-loop, autonomous workflow for discovering and optimizing HEA catalysts, as implemented in advanced platforms like CRESt and AMDEE.

Outlier Detection in Machine Learned Potentials

This diagram outlines the critical process of identifying and handling outliers when training ML models on potential energy surfaces (PES) for reactive HEA systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for HEA Catalyst Synthesis via Carbothermal Shock

This table details essential components for robotic, high-throughput synthesis of HEA nanoparticles, as used in systems like CRESt [18].

| Item Name | Function / Role in Experiment | Technical Specification & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salt Precursors | Source of the metallic elements in the HEA. | e.g., Chlorides or nitrates of Pd, Pt, Cu, Au, Ir, etc. Prepared as aqueous or organic solutions for robotic liquid handling. |

| Carbon Support | Substrate for HEA nanoparticle nucleation and growth. Provides high surface area and electrical conductivity. | Typically, carbon black or graphene. Must be uniformly dispersible in solvent. |

| Carbothermal Shock System | High-temperature reactor for rapid synthesis. | Joule heating system capable of rapid temperature spikes (~1500-2000 K for seconds) and rapid quenching. Essential for forming single-phase solid solutions [18]. |

| Robotic Liquid Handler | Automated precision dispensing of precursor solutions. | Critical for ensuring compositional accuracy and homogeneity across hundreds of parallel experiments. |

| Automated SEM | In-line characterization of nanoparticle size, morphology, and phase homogeneity. | Integrated with LVLMs (Large Vision-Language Models) for real-time microstructural analysis and anomaly detection [18]. |

Data Quality & Preprocessing FAQs

Why is data preprocessing considered the most critical step in our ML pipeline for catalyst research?

Data preprocessing is crucial because the quality of your input data directly determines the reliability of your model's outputs. In catalyst research, where we deal with complex properties like adsorption energies, the principle of "garbage in, garbage out" is paramount [22] [23]. Data practitioners spend approximately 80% of their time on data preprocessing and management tasks [22]. For catalyst optimization, this step ensures that the subtle patterns and relationships learned by the model are based on real catalytic properties and not artifacts of noisy or incomplete data [24].

What are the most common data quality issues that impact catalyst ML models?

The table below summarizes frequent data challenges and their potential impact on catalyst discovery research.

| Data Quality Issue | Description | Potential Impact on Catalyst Research |

|---|---|---|

| Missing Values [25] [26] | Absence of data in required fields. | Incomplete feature vectors for catalyst compositions or properties, leading to biased models. |

| Inconsistency [27] | Data that conflicts across sources or systems. | Conflicting adsorption energy values from different computational methods (e.g., DFT vs. MLFF). |

| Invalid Data [27] | Data that does not adhere to predefined rules or formats. | Catalyst formulas or crystal structures that do not conform to chemical rules or expected patterns. |

| Outliers [25] | Data points that distinctly stand out from the rest of the dataset. | Atypical adsorption energy measurements that could skew model predictions if not properly handled. |

| Duplicates [22] [28] | Identical or nearly identical records existing multiple times. | Over-representation of certain catalyst compositions, giving them undue weight during model training. |

| Imbalanced Data [25] | Data that is unequally distributed across target classes. | A dataset where high-performance catalysts are rare, biasing the model toward the more common low-performance class. |

Our dataset of catalyst adsorption energies has many missing values. How should we handle them?

The strategy depends on the extent and nature of the missing data [25]:

- For a small percentage of missing values: Use imputation to estimate and fill in the gaps. For continuous variables (e.g., a binding energy), the mean or median is often used. For discrete variables (e.g., a specific surface site), the mode is appropriate [23] [29].

- For a large percentage of missing values in a single feature: Consider removing the entire feature/column from the dataset, as it may contain too little information to be useful [25] [23].

- For a row with multiple missing values: If an entire catalyst record is missing too many critical properties, it may be best to remove that row/record from the dataset [25].

How do we know if our catalyst data is "clean enough" to proceed with model training?

You can use quantitative Data Quality Metrics to objectively assess your dataset's readiness [27]. The following table outlines key metrics to track.

| Data Quality Metric | Target for Catalyst Research | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|

| Completeness [27] | >95% for critical features (e.g., adsorption energy, surface facet). | (1 - (Number of missing values / Total records)) * 100 |

| Uniqueness [27] | >99% (near-zero duplicates). | Count of distinct catalyst records / Total records |

| Validity [27] | 100% (all data conforms to rules). | Check adherence to chemical rules (e.g., valency, composition). |

| Consistency [27] | >98% agreement across sources. | Cross-reference with trusted sources (e.g., Materials Project [24]). |

Troubleshooting Guides

Model Performance Issue: Poor Predictive Accuracy on New Catalyst Candidates

Symptoms: Your model performs well on training data but shows low accuracy when predicting the properties of new, unseen catalyst compositions.

Diagnosis: This is a classic sign of overfitting, where the model has learned the noise and specific details of the training data instead of the underlying generalizable patterns [25] [23]. In catalyst research, this can happen if the training dataset is too small or not representative of the broader search space.

Resolution:

- Apply Data Reduction & Feature Selection: Use techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the number of input features and force the model to focus on the most critical descriptors [25]. This was crucial in a recent study screening nearly 160 metallic alloys for CO2 to methanol conversion, where managing data complexity was key [24].

- Implement Cross-Validation: Split your data into k subsets (folds). Use k-1 folds for training and the remaining fold for validation. Repeat this process k times to ensure your model's performance is consistent across different data splits [25].

- Simplify the Model: Reduce model complexity by tuning hyperparameters, or try a different, simpler algorithm that is less prone to overfitting [25].

The following workflow outlines the troubleshooting process for a model suffering from overfitting.

Model Performance Issue: Consistently Low Accuracy on All Data

Symptoms: The model fails to learn meaningful patterns and performs poorly on both training and validation data.

Diagnosis: This is typically a case of underfitting, often caused by a dataset that is too small, lacks relevant features, or contains too much noise for the model to capture the underlying trends [25].

Resolution:

- Acquire More Data: If possible, expand your dataset with additional catalyst samples. In computational research, this can be done by generating more data points through high-throughput calculations using machine-learned force fields (MLFFs), which are significantly faster than DFT [24].

- Perform Feature Engineering: Create new, more informative features from your existing data. For catalyst design, this could involve creating interaction terms between existing descriptors or deriving new, more powerful descriptors, such as the Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) [24].

- Handle Outliers and Noise: Use statistical methods (e.g., box plots) to identify and address outliers that may be disrupting the learning process [25]. Ensure your data cleaning protocols are robust.

- Increase Model Complexity: If the data is sufficient and clean, try using a more complex model that can capture more intricate patterns.

Symptoms: The same catalyst is described with different properties or identifiers when data is integrated from different databases (e.g., OC20, Materials Project) or computational methods.

Diagnosis: A data consistency problem, often arising during the data integration phase when merging disparate sources [26] [27].

Resolution:

- Standardization: Enforce uniform data formats across all sources. For example, ensure all chemical formulas and surface facet notations follow the same convention [27].

- Cross-System Validation: Implement a validation check that compares key data points (e.g., elemental composition, crystal structure) across your source systems and flags discrepancies for manual review [27].

- Use a Validation Protocol: As demonstrated in advanced ML workflows for catalysts, establish a benchmark to validate data from approximate methods (like MLFFs) against a gold standard (like DFT) to ensure consistency and accuracy across your data pipeline [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and libraries essential for data preprocessing in machine learning-based research.

| Tool / Library | Function | Application in Catalyst & Outlier Research |

|---|---|---|

| Pandas (Python) [26] | Data cleaning, transformation, and aggregation. | Ideal for loading, exploring, and cleaning datasets of catalyst properties before model training. |

| Scikit-learn (Python) [26] | Feature selection, normalization, and encoding. | Provides robust scalers (Standard, Min-Max) and dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA. |

| MATLAB [26] | Numerical computing and data cleaning. | Useful for cleaning multiple variables simultaneously and identifying messy data via its Data Cleaner app. |

| OpenRefine [26] | Cleaning and transforming messy data. | A standalone tool for handling large, heterogeneous datasets, such as those compiled from multiple literature sources. |

| LakeFS [22] | Data version control and pipeline isolation. | Creates reproducible, isolated branches of your data lake for different preprocessing experiments, which is critical for research auditability. |

| OCP (Open Catalyst Project) [24] | Pre-trained machine-learned force fields. | Accelerates the generation of adsorption energy data for catalysts, expanding training datasets efficiently. |

Standard Experimental Protocol for Data Preprocessing

The following diagram maps the end-to-end data preprocessing workflow, from raw data acquisition to model-ready datasets. Adhering to this protocol ensures consistency and reproducibility in your research.

ML Techniques in Action: From Catalyst Design to Smart Anomaly Detection

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Modeling Catalyst Chemical Environments

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Training Issues

Q: My GNN model fails to converge when predicting adsorption energies. What could be wrong? A: This is often related to data quality or model architecture. First, check for outliers in your training data using the IQR or Z-score method, as they can destabilize training [30]. Ensure your model uses 3D structural information of the catalyst-adsorbate complex; models that only consider 2D graph connectivity may lack crucial spatial information for accurate energy predictions [31] [32]. Also, verify that your node (atom) and edge (bond) features are correctly specified and normalized.

Q: The model performs well on validation data but poorly on new catalyst compositions. How can I improve generalization? A: This indicates overfitting. Consider these approaches:

- Data Expansion: Incorporate data from large, diverse datasets like the Open Catalyst Project (OCP), which contains over 1.2 million DFT-relaxed structures [32].

- Transfer Learning: Start with a model pre-trained on a large dataset (e.g., OCP) and fine-tune it on your smaller, specific dataset.

- Architecture Choice: Use GNN architectures specifically designed for molecular systems, such as DimeNet++, which can more effectively capture geometric and relational information [32].

Q: How can I identify and handle outliers in my catalyst dataset before training? A: Outliers can severely impact model performance, especially in linear models and error metrics [30]. The table below summarizes two common methods:

| Method | Principle | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| IQR Method [30] | Identifies data points outside the range [Q1 - 1.5×IQR, Q3 + 1.5×IQR]. | General-purpose, non-parametric outlier detection for any data distribution. |

| Z-score Method [30] | Flags data points where the Z-score (number of standard deviations from the mean) is beyond a threshold (e.g., ±3). | Best for data that is approximately normally distributed. |

Data & Feature Engineering

Q: What is the best way to represent a catalyst-adsorbate system as a graph for a GNN? A: The catalyst-adsorbate complex should be represented as a graph where nodes are atoms and edges are chemical bonds or interatomic distances [31] [32].

- Node Features: Atomic number, formal charge, hybridization, number of bonds.

- Edge Features: Bond type (single, double, etc.), bond length, spatial distance.

- Global Features: Overall charge, system-level properties.

Q: How can strain engineering be incorporated into a GNN model for catalyst screening? A: To model the effect of strain, the strain tensor (ε) must be included as an input feature. One effective method is to use a GNN (like DimeNet++) to learn a representation from the atomic structure, which is then combined with the strain tensor in a subsequent neural network to predict the change in adsorption energy (ΔEads) [32]. This approach allows for the exploration of a high-dimensional strain space to identify patterns that break scaling relationships.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening of Strain-Engineered Catalysts

This protocol outlines the workflow for using GNNs to predict the adsorption energy response of catalysts under strain, based on the methodology from [32].

1. Dataset Curation:

- Source: Extract catalyst-adsorbate complexes from a foundational database like the Open Catalyst Project (OCP) [32].

- Focus: Filter for a specific class of catalysts (e.g., Cu-based binary alloys) and a set of relevant small-molecule adsorbates (e.g., CO, NH₃, *H).

- Apply Strain: For each complex, generate multiple randomly generated strain tensors (ε1, ε2, ε6) within a physiologically relevant range (e.g., -3% to +3%).

2. Data Generation with DFT:

- For each strained catalyst and catalyst-adsorbate complex, perform a DFT relaxation to find the lowest-energy atomic configuration.

- Calculate the strained adsorption energy:

Eadsε = E(Catalyst_ε + Adsorbate) - E(Catalyst_ε) - E(Adsorbate). - Compute the target label:

ΔEads(ε) = Eadsε - Eads(where Eads is the unstrained adsorption energy).

3. Model Training & Prediction:

- Architecture: Employ a GNN (e.g., DimeNet++) to process the relaxed atomic structure. The output graph-level embedding is then fed into a neural network alongside the strain tensor.

- Inputs: Relaxed atomic structure (graph) and the applied strain tensor (ε).

- Output: Predicted ΔEads(ε).

- Screening: Use the trained model to rapidly predict ΔEads for a vast number of candidate catalysts and strain patterns, identifying promising candidates for further experimental validation.

Protocol 2: Outlier Detection in Catalyst Property Datasets

This protocol ensures data quality by identifying anomalous data points before model training [30].

1. Data Preparation:

- Collect the target property data (e.g., adsorption energies, turnover frequencies) for your catalyst dataset.

2. Apply IQR Method:

- Calculate the first quartile (Q1, 25th percentile) and third quartile (Q3, 75th percentile) of the data.

- Compute the Interquartile Range (IQR):

IQR = Q3 - Q1. - Define the lower and upper bounds:

Lower Bound = Q1 - 1.5 * IQR,Upper Bound = Q3 + 1.5 * IQR. - Data points falling outside the [Lower Bound, Upper Bound] interval are considered outliers.

3. Validation:

- Visually inspect the identified outliers using a box plot.

- Investigate the source of outliers to determine if they are due to measurement errors, faulty sensors, or represent a rare but valid catalytic phenomenon [30].

Visualization Specifications

Diagram 1: GNN for Catalyst Strain Screening

Diagram 2: Message Passing in a Molecular Graph

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential computational tools and datasets for GNN-based catalyst research.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Open Catalyst Project (OCP) Dataset [32] | A large-scale dataset of over 1.2 million DFT relaxations of catalyst-adsorbate structures, providing a foundational resource for training and benchmarking GNN models. |

| DimeNet++ Architecture [32] | A GNN architecture that effectively incorporates directional message passing, making it well-suited for predicting quantum chemical properties like adsorption energies. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [32] | The computational method used to generate high-quality training data, such as adsorption energies and relaxed atomic structures, for GNN models. |

| Scikit-Learn [33] | A Python library offering a wide range of tools for classical machine learning and data preprocessing, including outlier detection methods (e.g., IQR calculation). |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow [33] | Open-source deep learning frameworks used to build, train, and deploy complex GNN models. |

Automatic Graph Representation (AGRA) for High-Throughput Catalyst Screening

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core advantage of AGRA over other graph representation methods like the Open Catalyst Project (OCP)? AGRA provides excellent transferability and a reduced computational cost. It is specifically designed to gather multiple adsorption geometry datasets from different systems and combine them into a single, universal model. Benchmarking tests show that AGRA achieved an RMSD of 0.053 eV for ORR datasets and an average of 0.088 eV RMSD for CO2RR datasets, demonstrating high accuracy and versatility [34] [35].

Q2: My model's performance is poor on a new catalyst system. How can I improve its extrapolation ability? This is often due to limited diversity in the training data. AGRA's framework is designed for excellent transferability. You can improve performance by combining your existing dataset with other catalytic reaction datasets (e.g., combining ORR and CO2RR data) and retraining a universal model with AGRA. This approach has been shown to maintain an RMSD of around 0.105 eV across combined datasets and successfully predict energies for new, unseen systems [35].

Q3: The graph representation for my input structure seems incorrect. What are the key connection criteria? AGRA uses automated, proximity-based edge connections. The critical parameters are:

- Adsorbate-Adsorbate Connection: Atoms are connected if the interatomic distance is less than 1.8 Å [35].

- Adsorbate-Substrate Connection: An atom of the adsorbate is connected to the catalyst if the interatomic distance is lower than 2.3 Å [35].

- Substrate-Substrate Connection: For two substrate atoms, the cutoff is 2.8 Å [35]. Ensure your input geometry file is correct and that the specified adsorbate is correctly identified by the algorithm.

Q4: How does AGRA handle different adsorption site geometries automatically? The algorithm automatically identifies the adsorption site type based on the number of catalyst atoms connected to the adsorbate [35]:

- 1 connected atom: 'On-top' geometry.

- 2 connected atoms: 'Bridge' geometry.

- 3 connected atoms: Either 'hollow-fcc' or 'hollow-hcp' structures (determined by subsurface configuration). This feature is consistent because the node count depends only on the adsorption site type, not the initial slab size.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Computational Cost or Long Processing Time

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Large initial slab size in the input geometry file. | AGRA extracts the local chemical environment, reducing redundant atoms. The processing time is largely independent of the original slab size [35]. |

| Complex adsorbate with many atoms. | The algorithm is efficient, but graph generation time will scale with the number of atoms in the localized region. This is typically less costly than methods that process the entire slab [35]. |

Issue 2: Inaccurate Graph Representation or Missing Bonds

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Incorrect identification of the adsorbate. | Double-check the user input specifying the adsorbate species for analysis. The algorithm uses this to extract the correct molecule indices [35]. |

| Neighbor list cutoffs are not capturing all interactions. | The algorithm uses an atomic radius-based neighbor list with a radial cutoff multiplier of 1.1 for coarse-grained adjustment. This is usually sufficient, but verify the neighbor list in the initial structure [35]. |

| Issues with periodic boundary conditions. | The algorithm unfolds bonds along the cell edge to account for periodicity. Redundant atoms generated from this process are automatically removed [35]. |

Issue 3: Poor Model Performance and Low Prediction Accuracy

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| The model is trained on a single, narrow dataset. | Utilize AGRA's ability to combine multiple datasets (e.g., from different reactions or material systems) into a single model to boost extrapolation ability and performance [35]. |

| Inappropriate or insufficient node/edge descriptors. | The default node feature vectors are based on established methods [35]. The tool allows for easy modification of node and edge descriptors via JSON files to explore which spatial and chemical descriptors are most important for your specific system [35]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

AGRA Graph Construction Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the automated process for generating a graph representation of an adsorption site.

Key Experimental Results and Performance Data

Table 1: AGRA Model Performance on Catalytic Reaction Datasets [35]

| Catalytic Reaction | Adsorbates | Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) | O / OH | 0.053 eV |

| Carbon Dioxide Reduction Reaction (CO2RR) | CHO / CO / COOH | 0.088 eV (average) |

| Combined Dataset Subset | Multiple | 0.105 eV |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Resources [35]

| Item / Software | Function |

|---|---|

| Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) | A Python package used to analyze a material system's surface and handle atomistic simulations [35]. |

| NetworkX | A Python library used to embed nodes and construct the graph representation of the extracted geometry [35]. |

| Geometry File | The initial input file (e.g., in .xyz or similar format) containing the atomic structure of the adsorbate/catalyst system [35]. |

| Node/Edge Descriptor JSON Files | Configuration files that allow for easy modification and testing of atomic feature vectors and bond attributes without changing core code [35]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Used for calculating reference adsorption energies to train and validate the machine learning models [35]. |

Detailed Methodology: AGRA Graph Generation

The framework is built using Python. The following steps detail the graph construction process [35]:

- Input: The algorithm requires a geometry file of the adsorbate/catalyst system.

- Adsorbate Identification: The user must specify the desired adsorbate to analyze. The algorithm then identifies the molecule and extracts its atomic indices from the input structure.

- Neighbor List Generation: Using the ASE

neighborlistmodule, a neighbor list is generated for each atom based on metallic radii. A radius multiplier of 1.1 is applied for coarse-grained adjustment. - Edge Connection:

- Two adsorbate atoms are connected if the interatomic distance is less than 1.8 Å.

- An adsorbate atom is connected to a substrate atom if the distance is less than 2.3 Å.

- Two substrate atoms are connected if they share a Voronoi face and the interatomic distance is lower than the sum of the Cordero covalent bond lengths, with a general cutoff of 2.8 Å.

- Local Environment Extraction: The algorithm selects catalyst atoms connected to the adsorbate and their neighbors, removing redundant atoms created by periodic boundary conditions.

- Graph Construction: The final graph is generated where nodes represent atoms and edges represent bonds. Feature vectors are embedded at each node and edge using established procedures, including properties like atomic number and Pauling electronegativity.

Smart K-Nearest Neighbor (SKOD) Outlier Detection for Physiological Signal Analysis

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My SKOD model is flagging an excessive number of data points as outliers in my physiological signal dataset. What could be the cause?

A1: A high false positive rate in outlier detection often stems from an improperly chosen value for K (the number of neighbors) or an unsuitable distance metric. An excessively small K makes the model overly sensitive to local noise, while a large K may smooth out genuine anomalies. Furthermore, physiological signals like EEG and ECG have unique statistical properties; the standard Euclidean distance might not capture their temporal dynamics effectively. It is recommended to perform error analysis on a validation set to plot the validation error against different values of K and select the value where the error is minimized [36]. For signal data, consider using dynamic time warping (DTW) as an alternative distance metric.

Q2: How can I determine if a detected outlier is a critical symptom fluctuation or merely a measurement artifact in my Parkinson's disease study?

A2: Distinguishing between a genuine physiological event and an artifact requires a multi-modal verification protocol. First, correlate the outlier's timing across all recorded signals (e.g., EEG, ECG, EMG). A true symptom fluctuation, such as in Parkinson's disease, may manifest as co-occurring significant changes in multiple channels—for instance, a simultaneous power increase in frontal beta-band EEG and a change in time-domain ECG characteristics [37]. Second, employ robust statistical methods like Cook's Distance to determine if the suspected data point has an unduly high influence on your overall model. Data points with high influence that are also physiologically plausible should be investigated as potential biomarkers rather than discarded [38].

Q3: When applying SKOD for catalyst optimization, my model's performance degrades with high-dimensional d-band descriptor data. How can I improve its efficiency and accuracy?

A3: The "curse of dimensionality" severely impacts distance-based algorithms like KNN. As the number of features (e.g., d-band center, d-band width, d-band filling) increases, the concept of proximity becomes less meaningful. To mitigate this:

- Feature Selection: Use Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to identify and retain only the most relevant descriptors without sacrificing classification accuracy [39] [40].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to transform your high-dimensional feature set into a lower-dimensional space that retains most of the original variance, as demonstrated in studies analyzing electronic structure features of catalysts [1].

- Alternative Algorithms: For high-dimensional spaces, model-based methods like Isolation Forest can be more efficient, as they do not rely on distance measures and are built specifically for anomaly detection [41].

Q4: What are the best practices for treating outliers once they are detected in my research data?

A4: The treatment strategy depends on the outlier's identified cause.

- Remove: If an outlier is conclusively proven to be a result of a measurement error (e.g., sensor malfunction, data entry error) and is not part of the natural population, it can be removed.

- Cap/Winsorize: For outliers that represent extreme but valid values, use Winsorizing techniques. This method caps extreme values at a specific percentile (e.g., the 5th and 95th), reducing their influence without discarding the data point entirely [38].

- Model: In some cases, it may be appropriate to use robust statistical models or algorithms that are less sensitive to outliers.

Comparative Analysis of Outlier Detection Techniques

The following table summarizes key outlier detection methods relevant to research in physiological signals and catalyst optimization.

Table 1: Comparison of Outlier Detection Techniques

| Technique | Type | Key Principle | Pros | Cons | Ideal Use-Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-Score | Statistical | Flags data points that are a certain number of standard deviations from the mean. | Simple, fast, easy to implement [41]. | Assumes normal distribution; not reliable for skewed data [41]. | Initial, quick pass on normally distributed univariate data. |

| IQR Method | Statistical | Identifies outliers based on the spread of the middle 50% of the data (Interquartile Range) [41]. | Robust to non-normal data and extreme values; non-parametric [41]. | Less effective for very skewed distributions; inherently univariate [41]. | Creating boxplots; a robust default for univariate analysis. |

| K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | Proximity-based | Classifies a point based on the majority class of its 'K' nearest neighbors in feature space [36]. | Simple, intuitive, and effective for low-dimensional data. | Computationally expensive with large datasets; suffers from the curse of dimensionality [36]. | Low-dimensional datasets where local proximity is a strong indicator of class membership. |

| Isolation Forest | Model-based | Isolates anomalies by randomly selecting features and splitting values; anomalies are easier to isolate [41]. | Efficient with high-dimensional data; does not require a distance metric [41]. | Requires an estimate of "contamination" (outlier fraction) [41]. | High-dimensional datasets, such as those with multiple catalyst descriptors or physiological features [1]. |

| Local Outlier Factor (LOF) | Density-based | Compares the local density of a point to the densities of its neighbors to find outliers [41]. | Effective for detecting local outliers in data with clusters of varying density [41]. | Sensitive to the choice of the number of neighbors (k); computationally costly [41]. | Identifying subtle anomalies in heterogeneous physiological data where global methods fail. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing SKOD for Catalyst Descriptor Screening

This protocol outlines the application of a Smart K-Nearest Neighbor Outlier Detection (SKOD) framework to identify anomalous catalysts based on their electronic and compositional properties, a critical step in robust machine learning-guided catalyst design [1].

Data Preparation and Feature Definition

- Dataset Compilation: Assemble a dataset of catalyst records. Each record should include key intrinsic properties known to govern catalytic activity. For electrocatalysts, this includes d-band descriptors (d-band center, d-band width, d-band filling, d-band upper edge) and adsorption energies for key species (C, O, N, H), all relative to the Fermi level [1].

- Feature Engineering: To address dimensionality, perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA). This transforms the original d-band descriptors into a new, lower-dimensional feature space that captures the maximum variance, simplifying the distance calculation for KNN [1].

SKOD Model Training and Execution

- Distance Metric Selection: For continuous, high-dimensional data like catalyst descriptors, the Euclidean distance is a standard starting point.

- Determining Optimal K: Split the dataset into training and validation sets. Run the KNN algorithm on the validation set with a range of K values (e.g., 1 to 15). Plot the validation error against K and select the value that minimizes the error, ensuring the model is neither overfitted nor oversmoothed [36].

- Outlier Identification: For a new catalyst candidate, the SKOD algorithm:

- Calculates the distance to all other catalysts in the dataset.

- Identifies the K-nearest neighbors.

- Computes the average adsorption energy (or other target property) of these neighbors.

- Flags the candidate as an outlier if its actual property value deviates from this average by a pre-defined, statistically significant threshold.

Validation and Interpretation

- Feature Importance Analysis: Use SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis on the flagged outliers to determine which d-band descriptors (e.g., d-band filling for O adsorption) were most influential in their classification as anomalies [1].

- Cross-Domain Validation: Correlate the outlier status with experimental performance metrics (e.g., overpotential, conversion efficiency) to determine if these statistical outliers represent genuinely failed catalysts or promising, non-obvious candidates.

Workflow Visualization: SKOD in Catalyst Research

The following diagram illustrates the integrated role of Smart K-Nearest Neighbor Outlier Detection within a broader machine learning workflow for catalyst optimization and discovery.

SKOD Catalyst Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational and Data Resources

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to SKOD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cobalt-Based Catalysts | A class of heterogeneous catalysts (e.g., Co₃O₄) prepared via precipitation for processes like VOC oxidation [33]. | Serves as a model system for generating data on catalyst composition, properties, and performance, which is used to build and test the SKOD model. |

| d-band Descriptors | Electronic structure features (d-band center, width, filling) calculated from first principles that serve as powerful predictors of adsorption energy and catalytic activity [1]. | These are the key input features for the SKOD model when screening and identifying outlier catalysts in a high-dimensional material space. |

| BioVid Heat Pain Dataset | A public benchmark dataset containing multimodal physiological signals (EMG, SCL, ECG) for pain assessment research [39] [40]. | Provides real, complex physiological data for developing and validating the SKOD method in a biomedical context, distinguishing pain levels. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | A computational method for feature selection that optimizes a problem by iteratively trying to improve a candidate solution [39]. | Used to reduce the dimensionality of the feature space by removing redundant features, improving SKOD's computational efficiency and accuracy. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game-theoretic approach to explain the output of any machine learning model [1]. | Critical for interpreting the SKOD model's outputs, identifying which features were most important in flagging a specific catalyst or signal as an outlier. |

Isolation Forests and Local Outlier Factor (LOF) for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my Isolation Forest model detect a much larger number of anomalies than LOF on the same dataset?

This is a common observation due to the fundamental differences in how the algorithms define an anomaly. In a direct comparison on a synthetic dataset of 1 million system metrics points, Isolation Forest detected 20,000 anomalies, while LOF detected only 487 [42].

The primary reason is that Isolation Forest identifies points that are "easily separable" from the majority of the data, which can include a broader set of deviations [43]. LOF, in contrast, is more precise and focuses specifically on points that have a significantly lower local density than their neighbors [44]. Therefore, LOF's anomalies are a more selective subset. The choice between them should be guided by your goal: use Isolation Forest for initial, broad screening and LOF for identifying highly localized, subtle outliers [42].

Q2: How should I interpret the output scores from LOF and Isolation Forest?

The interpretation of the anomaly scores differs significantly between the two algorithms, which is a frequent source of confusion.

- Isolation Forest: The algorithm outputs an anomaly score based on the average path length to isolate a data point. A score closer to 1 indicates anomalies, while scores closer to 0 are considered normal points [43]. Some implementations also provide a binary output of

-1for outliers and1for inliers [45]. - Local Outlier Factor (LOF): The LOF score is a ratio of local densities. A score of approximately 1 means the point's density is comparable to its neighbors (normal). A score significantly greater than 1 indicates an outlier, and a score below 1 can indicate an inlier [44]. A major challenge is that there is no universal threshold for "significantly greater than 1," as it depends on your specific dataset and parameters [44].

Q3: What is the most critical parameter to tune for LOF, and how do I choose its value?

The most critical parameter for LOF is n_neighbors (often referred to as k), which determines the locality of the density estimation [44].