Machine Learning in Catalyst Discovery: Accelerating the Development of Sustainable Materials and Therapeutics

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in accelerating the discovery and optimization of novel catalyst materials.

Machine Learning in Catalyst Discovery: Accelerating the Development of Sustainable Materials and Therapeutics

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in accelerating the discovery and optimization of novel catalyst materials. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview of how ML methods are reshaping traditional R&D pipelines. The content covers foundational ML concepts for materials science, delves into specific high-throughput computational and experimental methodologies, addresses key challenges in model training and experimental reproducibility, and examines rigorous validation frameworks that bridge computational predictions with experimental results. By synthesizing insights from recent breakthroughs, this review serves as a guide for leveraging ML to design efficient catalysts for applications ranging from green energy to pharmaceutical synthesis, ultimately aiming to reduce both development timelines and costs.

The New Paradigm: How Machine Learning is Reshaping Catalyst Discovery

Shifting from Trial-and-Error to a Predictive Science

The discipline of catalysis, a cornerstone of energy, environmental, and materials sciences, is undergoing a profound transformation. For decades, the discovery and optimization of catalysts have been largely driven by empirical trial-and-error strategies and theoretical simulations, which are increasingly limited by inefficiencies when addressing complex catalytic systems and vast chemical spaces [1]. The emergence of machine learning (ML), a key branch of artificial intelligence, is fundamentally reshaping this conventional research paradigm. ML offers a low-cost, high-throughput, and high-precision path to uncovering hidden structure-performance relationships and accelerating catalyst design [1]. This shift represents a move from an intuition-driven and theory-driven past toward a future characterized by the integration of data-driven models with physical principles, where ML acts not merely as a predictive tool but as a "theoretical engine" that contributes to mechanistic discovery and the derivation of general catalytic laws [1]. This whitepaper outlines the core methodologies, workflows, and tools enabling this transition, providing researchers with a framework for leveraging ML in the exploration of new catalyst materials.

A Hierarchical Framework for ML in Catalysis

The application of machine learning in catalysis can be understood through a hierarchical "three-stage" framework that progresses from purely data-driven tasks toward increasingly physics-informed modeling [1].

Stage 1: Data-Driven Catalyst Screening and Prediction

At this foundation level, ML models are employed to rapidly predict catalytic properties, such as activity, selectivity, and stability, based on existing datasets. This enables the high-throughput virtual screening of vast material spaces, which would be prohibitively expensive and time-consuming to explore experimentally or with first-principles simulations [1]. The primary goal is to identify promising candidate materials from a large pool of possibilities.

Stage 2: Physics-Based and Microkinetic Modeling

This stage involves a tighter integration of ML with physical laws to create more interpretable and generalizable models. A key application is the development of machine-learned force fields (MLFFs), which can achieve near-quantum mechanical accuracy in simulating molecular dynamics while being computationally orders of magnitude faster than density functional theory (DFT) [2] [3]. These force fields enable accurate and efficient relaxation of adsorbates on catalyst surfaces and the simulation of reaction dynamics under realistic conditions, thereby bridging the gap between static snapshot calculations and dynamic catalytic behavior [3].

Stage 3: Symbolic Regression and Theory-Oriented Interpretation

The most advanced stage uses ML not just for prediction but for scientific discovery itself. Techniques like symbolic regression can distill complex, high-dimensional relationships within the data into compact, human-interpretable mathematical expressions and descriptors [1]. For example, the SISSO (Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) method can identify the best low-dimensional descriptor from an immense pool of candidate features, potentially revealing new physical insights and catalytic design rules [1].

Core Machine Learning Workflows and Experimental Protocols

Workflow for High-Throughput Catalyst Screening Using Novel Descriptors

A sophisticated application of ML involves the creation of new, more comprehensive descriptors for catalyst discovery. The following workflow, developed for the discovery of catalysts for CO₂-to-methanol conversion, exemplifies this approach [2].

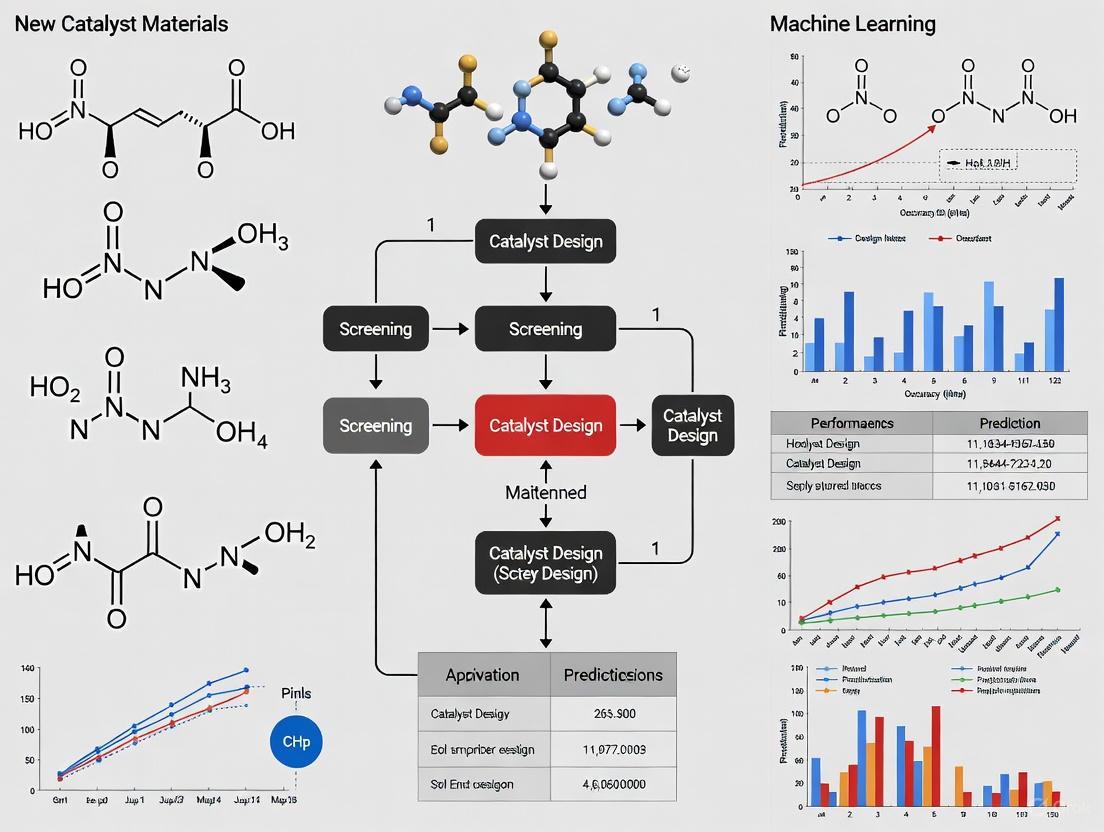

Diagram 1: High-throughput catalyst screening workflow.

Detailed Methodology:

- Search Space Selection: The process begins by defining a chemically relevant search space. In a recent study, this involved isolating 18 metallic elements (K, V, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Ga, Y, Ru, Rh, Pd, Ag, In, Ir, Pt, Au) that have prior experimental relevance for the CO₂ to methanol reaction and are present in the Open Catalyst 2020 (OC20) database to ensure ML model compatibility [2].

- Surface Generation: For each material, stable surfaces are generated across a range of Miller indices (e.g., from -2 to 2). The most stable surface terminations are selected based on their computed energy for subsequent steps [2].

- Adsorbate Configuration Engineering: Surface-adsorbate configurations are constructed for key reaction intermediates identified from the literature. For CO₂ hydrogenation to methanol, these typically include *H, *OH, *OCHO (formate), and *OCH3 (methoxy) [2].

- Geometry Optimization with MLFF: The engineered configurations are optimized using a pre-trained machine-learned force field, such as the Equiformer V2 from the Open Catalyst Project (OCP). This step is critical as it relaxes the atomic positions to their minimum energy state and is ~10,000 times faster than equivalent DFT calculations [2].

- Validation Against DFT: To ensure reliability, a subset of the MLFF-optimized adsorption energies is benchmarked against explicit DFT calculations. The target is to maintain a mean absolute error (MAE) for adsorption energies within an acceptable threshold, for example, 0.16 eV, which falls within the reported accuracy of advanced MLFFs [2].

- Descriptor Calculation: The core novel output is the Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED). This descriptor aggregates the binding energies for a specific adsorbate across different catalyst facets and binding sites, thus capturing the intrinsic heterogeneity of real-world nanoparticle catalysts better than a single-facet energy [2].

- Unsupervised Learning and Candidate Identification: The AEDs for all materials in the search space are compared using a distance metric like the Wasserstein distance, which measures the similarity between two probability distributions. Hierarchical clustering is then applied to group catalysts with similar AED profiles. New candidate materials (e.g., ZnRh, ZnPt₃) are proposed based on their proximity to the AEDs of known effective catalysts in this clustering space [2].

Protocol for Accurate Simulation of Transition Metal Catalysts

Simulating transition metal catalysts with dynamic methods like MLFFs requires high-quality underlying data. The Weighted Active Space Protocol (WASP) was developed to generate accurate machine-learned potentials for multireference systems, a long-standing challenge in quantum chemistry [3].

Diagram 2: WASP method for accurate ML potentials.

Detailed Methodology:

- Initial Sampling: First, a set of molecular geometries is sampled along the relevant reaction pathway.

- High-Level Wavefunction Calculation: For each of these sampled geometries, a high-level, accurate wavefunction is calculated using a multireference quantum chemistry method like Multiconfiguration Pair-Density Functional Theory (MC-PDFT). This method is particularly good at describing the complex electronic structures of transition metals but is prohibitively slow for dynamics [3].

- The WASP Algorithm - Labeling Consistency: The core innovation is the Weighted Active Space Protocol (WASP). For any new geometry encountered during simulation, WASP generates a consistent wavefunction by blending wavefunctions from the pre-computed, nearby sampled geometries. "The closer a new geometry is to a known one, the more strongly its wave function resembles that of the known structure" [3]. This ensures that every point on the reaction pathway is assigned a unique and reliable label (energy and forces).

- ML Potential Training and Use: These uniquely labeled data points are used to train a machine-learned interatomic potential. This resulting potential can then perform molecular dynamics simulations that retain the accuracy of the high-level MC-PDFT method but at a computational cost that is orders of magnitude lower, enabling the simulation of catalytic dynamics under realistic conditions of temperature and pressure [3].

The following table details key computational and data resources that form the essential toolkit for modern, ML-driven catalysis research.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Catalysis

| Item Name | Type/Function | Key Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Open Catalyst Project (OCP) Datasets & Models [2] | Pre-trained Machine-Learned Force Fields (e.g., Equiformer_V2) | Accelerated calculation of adsorption energies and geometry optimization of adsorbate-catalyst systems, enabling high-throughput screening. |

| Weighted Active Space Protocol (WASP) [3] | Algorithm/Framework | Generates consistent, accurate ML potentials for challenging multireference systems like transition metal catalysts, bridging accuracy and efficiency. |

| SISSO (Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) [1] | Feature Selection Algorithm | Identifies optimal physical descriptors from a vast space of candidate features, aiding in model interpretability and discovery of design principles. |

| Materials Project Database [2] | Crystallographic and Energetic Database | Provides stable crystal structures and material properties for defining and sourcing initial catalyst models in a screening workflow. |

| Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) [2] | Novel Catalytic Descriptor | Represents the spectrum of adsorption energies across various facets and sites of a nanoparticle catalyst, providing a more holistic performance fingerprint. |

Critical Data and Performance Metrics

The performance of ML models in catalysis is quantitatively evaluated using specific metrics and is highly dependent on the quality and volume of the underlying data.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics and Data Requirements

| Metric | Typical Value/Range | Significance & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| MLFF Adsorption Energy MAE | ~0.16 - 0.23 eV [2] | Benchmark for model accuracy; lower MAE ensures reliability of predictions for adsorption energies, a critical property in catalysis. |

| MLFF Computational Speedup | Factor of 10⁴ or more vs. DFT [2] | Enables large-scale screening of thousands of materials that would be impossible with DFT alone. |

| WASP Simulation Speedup | Months to minutes [3] | Makes high-accuracy, dynamic simulation of complex transition metal catalysts feasible for practical research timelines. |

| Minimum Contrast Ratio for Visualizations | 3:1 [4] | Ensures that diagrams, charts, and user interface components are accessible and perceivable by users with low vision. |

The integration of machine learning into catalysis research marks a definitive shift from a trial-and-error discipline to a predictive science. Frameworks such as the three-stage progression from data-driven screening to symbolic regression provide a coherent path for this integration [1]. The development of advanced tools like MLFFs for high-throughput screening [2] and innovative methods like WASP for accurate simulation of transition metals [3] are solving long-standing challenges in the field. By adopting these methodologies and leveraging the growing ecosystem of standardized databases and algorithms, researchers can systematically navigate the vast chemical space to discover novel, high-performance catalyst materials with unprecedented speed and insight. The future of catalyst discovery is data-driven, physics-informed, and profoundly accelerated by machine learning.

The discovery and development of new materials have traditionally been driven by empirical trial-and-error strategies and theoretical simulations, which are often limited by inefficiencies when addressing complex systems and vast chemical spaces [1]. The materials challenge encompasses a very high-dimensional discovery or search space with millions of possible compounds, of which only a very small fraction have been experimentally explored [5]. In the context of catalyst discovery, this challenge is particularly acute, as even incremental improvements in catalytic performance can have substantial impacts on energy efficiency, environmental sustainability, and economic viability.

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative approach in materials science, offering a low-cost, high-throughput, and high-precision path to uncovering complex structure-property relationships and accelerating the discovery process [1]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three core machine learning paradigms—supervised, unsupervised, and active learning—within the framework of materials science research, with specific application to the discovery of novel catalyst materials for converting CO2 to methanol, a crucial step toward closing the carbon cycle [2].

Supervised Learning in Catalyst Discovery

Fundamental Principles and Workflow

Supervised learning operates on the principle of inferring a mapping function from labeled input-output pairs, where the algorithm learns to predict output variables from input data [1]. In catalytic materials science, this typically involves using computational or experimental data to build models that predict catalyst properties or performance based on material descriptors. The supervised learning workflow encompasses several critical stages: data acquisition and curation, feature engineering, model selection, training, and validation [1].

For catalyst discovery, supervised learning has been particularly valuable in predicting adsorption energies—a key descriptor of catalytic activity—based on electronic, geometric, or compositional features of catalyst materials [2]. This approach has significantly reduced the reliance on computationally intensive density functional theory (DFT) calculations, enabling more rapid screening of candidate materials.

Key Applications in Catalyst Design

A prominent application of supervised learning in catalyst discovery is the prediction of adsorption energy distributions (AEDs) across different catalyst facets, binding sites, and adsorbates [2]. In the study of CO2 to methanol conversion, researchers have employed gradient boosting tree algorithms to predict the γ'-phase solvus temperature (Tγ') of superalloys based on features characterizing atomic size difference and alloy mixing enthalpy [6]. The model achieved a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.93 on test data, demonstrating remarkable predictive accuracy for a key materials property [6].

Another significant application involves the use of machine-learned force fields (MLFFs) from the Open Catalyst Project (OCP) to predict adsorption energies of key reaction intermediates such as *H, *OH, *OCHO, and *OCH3 in CO2 to methanol conversion [2]. These MLFFs provide explicit relaxation of adsorbates on catalyst surfaces with a speed-up factor of 10^4 or more compared to DFT calculations while maintaining quantum mechanical accuracy [2].

Table 1: Supervised Learning Algorithms in Materials Science

| Algorithm | Primary Application | Key Strengths | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting Trees | Prediction of γ'-phase solvus temperature in superalloys [6] | Handles non-linear relationships, robust to outliers | R² = 0.93 on test data [6] |

| Equiformer_V2 MLFF | Prediction of adsorption energies for catalyst screening [2] | High speed (10⁴× faster than DFT), quantum mechanical accuracy | MAE = 0.16 eV for adsorption energies [2] |

| Symbolic Regression | Deriving interpretable descriptors from complex data [1] | Generates human-interpretable mathematical expressions | Identifies physically meaningful relationships [1] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Supervised Learning for Catalyst Screening

The implementation of a supervised learning workflow for catalyst discovery involves methodical steps:

Data Acquisition and Curation: Compile a dataset of known catalysts with target properties. For CO2 to methanol conversion, this may include nearly 160 metallic alloys with associated adsorption energies for key intermediates [2]. Data quality is paramount, as model performance heavily depends on it [1].

Feature Selection and Engineering: Identify relevant descriptors that effectively represent catalysts. This may involve correlation analysis (e.g., using Maximal Information Coefficient) to eliminate redundant features [6]. Common descriptors include atomic radius mismatches (δMV), mixing enthalpy (ΔHm), and electronic structure parameters [6].

Model Training and Validation: Split data into training and test sets, train the selected algorithm, and validate using appropriate metrics (e.g., MAE, R²). Implement cross-validation techniques to assess model robustness [1].

Prediction and Screening: Apply the trained model to predict properties of unknown catalysts in the search space, prioritizing candidates with promising predicted performance for further experimental validation [2].

Unsupervised Learning for Pattern Recognition in Materials Space

Fundamental Principles and Workflow

Unsupervised learning operates without labeled outputs, focusing instead on identifying inherent patterns, structures, or relationships within the input data [1]. In materials science, this approach is particularly valuable for exploring uncharted chemical spaces and discovering novel material families that might be overlooked by supervised methods constrained to existing knowledge [6].

The unsupervised learning workflow typically involves data preprocessing, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and pattern interpretation. These techniques allow researchers to group materials with similar characteristics, identify outliers, and map the broader materials landscape beyond known territories [7] [6].

Key Applications in Catalyst Design

Unsupervised learning has demonstrated significant utility in catalyst discovery through its ability to identify promising regions in vast compositional spaces. Researchers have employed techniques such as t-SNE clustering to group superalloys with similar characteristics, then identified clusters showing high predicted Tγ' that are distant from training data as target regions for experimental exploration [6]. This approach led to the discovery of nine new superalloys with distinct compositions, three of which showed improved Tγ' by approximately 50°C—a substantial enhancement in this materials class [6].

In the study of CO2 to methanol conversion, unsupervised learning has been applied to analyze adsorption energy distributions (AEDs) as probability distributions [2]. By quantifying similarity using the Wasserstein distance metric and performing hierarchical clustering, researchers have grouped catalysts with similar AED profiles, enabling systematic comparison with established catalysts and identification of new promising candidates such as ZnRh and ZnPt3 [2].

Table 2: Unsupervised Learning Techniques in Materials Science

| Technique | Primary Application | Key Strengths | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| t-SNE Clustering | Identifying novel superalloy compositions with high solvus temperature [6] | Effective visualization of high-dimensional data in 2D/3D | Discovery of 3 new superalloys with ~50°C improvement in Tγ' [6] |

| Hierarchical Clustering with Wasserstein Distance | Grouping catalysts by adsorption energy distribution similarity [2] | Compares probability distributions effectively | Identification of ZnRh and ZnPt3 as promising novel catalysts [2] |

| SHAP Analysis | Interpreting feature contributions to target properties [6] | Model-agnostic interpretability, reveals non-linear relationships | Identified δMV and ΔHm as linearly affecting Tγ' [6] |

Experimental Protocol: Unsupervised Learning for Novel Catalyst Discovery

Implementing unsupervised learning for catalyst discovery involves:

Data Representation: Encode catalyst compositions and structures into appropriate feature vectors. This may involve compositional features, structural descriptors, or property distributions such as AEDs [2].

Dimensionality Reduction: Apply techniques like t-SNE or UMAP to project high-dimensional data into 2D or 3D space for visualization and analysis [6].

Clustering Analysis: Perform clustering to group materials with similar characteristics. This helps identify regions in materials space with desirable properties [7] [6].

Interpretation and Target Selection: Use interpretability methods like SHAP analysis to understand the physical meaning behind clusters. Select candidate materials from promising clusters that are distinct from known materials [6].

Experimental Validation: Synthesize and characterize selected candidates to validate predicted properties and expand the materials database [6].

Diagram 1: Unsupervised learning workflow for catalyst discovery, from raw data to experimental validation.

Active Learning for Targeted Materials Design

Fundamental Principles and Workflow

Active learning represents an iterative, adaptive approach that combines elements of both supervised and unsupervised learning with strategic decision-making [5]. The core principle involves selectively choosing the most informative data points to evaluate next, based on current model predictions and associated uncertainties [5]. This approach is particularly powerful in materials science where experiments or computations are resource-intensive, as it aims to maximize information gain while minimizing the number of required evaluations.

The active learning workflow operates through a cyclic process: initial model training, uncertainty quantification, candidate prioritization, targeted experimentation, and model updating [5]. This closed-loop system enables efficient navigation of vast materials spaces by focusing resources on the most promising regions [8] [5].

Key Applications in Catalyst Design

Active learning has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in accelerating catalyst discovery by strategically guiding experimental and computational efforts. In the context of discovering novel molecular structures for carbon capture, the integration of active learning with generative AI significantly increased the number of high-quality candidates identified—from an average of 281 high-performing candidates without active learning to 604 with active learning prioritization out of 1000 novel candidates [8]. This approach prevents generative workflows from expending resources on nonsensical candidates and halts potential generative model decay [8].

Similarly, active learning with adjustable weights has been successfully applied to discover high-strength, high-ductility lead-free solder alloys [9]. The approach efficiently navigated the complex multi-objective optimization space by balancing exploration (sampling high-uncertainty regions) and exploitation (focusing on predicted high-performance regions) [9] [5].

Table 3: Active Learning Utility Functions and Applications

| Utility Function | Mechanism | Application Example | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement (EI) | Balances predicted performance and uncertainty [5] | Design of superalloys with high solvus temperature [6] | Identified regions with both high prediction and high uncertainty [6] |

| Queue Prioritization | Ranks candidates based on expected quality and model uncertainty [8] | Molecular discovery for carbon capture [8] | 115% increase in high-performing candidates identified [8] |

| Knowledge Gradient | Considers the value of information gained from next evaluation [5] | Targeted design of optoelectronic structures [5] | Improved computational efficiency in simulation-based design [5] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Active Learning for Catalyst Optimization

Implementing an active learning framework for catalyst discovery involves:

Initial Surrogate Model Development: Train an initial model on available data, which could be sparse at the beginning of the discovery process [5].

Utility Function Definition: Establish a utility or acquisition function that encodes both the predicted mean and associated uncertainties. Common functions include Expected Improvement, Upper Confidence Bound, and Knowledge Gradient [5].

Candidate Prioritization: Use the utility function to rank unexplored candidates and select the most promising ones for the next round of experimentation or computation [8].

Targeted Experimentation: Synthesize and characterize the prioritized candidates, focusing resources on the most informative samples [5].

Model Updating: Incorporate new data into the training set and update the surrogate model, refining predictions for subsequent iterations [5].

Diagram 2: Active learning closed-loop workflow for iterative materials optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Catalyst Discovery

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools and Databases for ML-Driven Catalyst Research

| Tool/Database | Type | Primary Function | Application in Catalyst Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open Catalyst Project (OCP) | Database & Models | Provides pre-trained machine-learned force fields (MLFFs) [2] | Rapid prediction of adsorption energies with DFT-level accuracy [2] |

| Materials Project | Database | Repository of calculated material properties and crystal structures [2] | Source of stable phase forms for initial candidate screening [2] |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Interpretability Tool | Explains model predictions by feature contribution analysis [6] | Identifies physical descriptors most relevant to catalytic performance [6] |

| Equiformer_V2 | Machine Learning Model | Graph neural network for materials property prediction [2] | Prediction of adsorption energies for catalyst surfaces [2] |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithms | Optimization Framework | Implements utility functions for active learning [5] | Guides iterative experimental design for catalyst optimization [5] |

Comparative Analysis and Integration of ML Approaches

Each machine learning paradigm offers distinct advantages and faces specific limitations in the context of catalyst discovery. Supervised learning provides powerful predictive capabilities but requires substantial labeled data and may be biased toward interpolation within known materials spaces [5]. Unsupervised learning enables exploration of novel materials regions without predefined labels but may identify patterns that lack direct relevance to target properties [6]. Active learning strategically navigates the exploration-exploitation trade-off but requires iterative experimentation and can be computationally intensive in early stages [5].

The most effective applications often integrate multiple approaches, such as using unsupervised learning to identify promising regions of materials space, supervised learning to predict properties within those regions, and active learning to guide iterative refinement [6]. This integrated approach was demonstrated in the discovery of superalloys with improved solvus temperature, where unsupervised clustering identified target regions, interpretable analysis confirmed their relevance, and similarity evaluation selected diverse candidates for experimental validation [6].

For CO2 to methanol catalyst discovery, the integration of these approaches has enabled the proposal of novel candidate materials such as ZnRh and ZnPt3, which exhibit promising adsorption energy distributions similar to known effective catalysts but with potential advantages in terms of stability [2]. This demonstrates the power of machine learning to not only optimize within known materials families but to discover entirely new candidate systems that might otherwise be overlooked.

The integration of machine learning methodologies into catalyst discovery represents a paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches to data-driven, targeted materials design. Supervised learning provides the predictive foundation, unsupervised learning enables exploration of uncharted materials spaces, and active learning offers strategic guidance for iterative optimization. Together, these approaches form a powerful framework for accelerating the discovery of novel catalyst materials, with demonstrated success in identifying promising candidates for critical reactions such as CO2 to methanol conversion.

As these methodologies continue to evolve, challenges remain in data quality and standardization, feature engineering, model interpretability, and generalizability [1]. Future directions include the development of small-data algorithms, standardized databases, and the synergistic integration of large language models with traditional machine learning approaches [1]. By addressing these challenges and advancing the integration of physical principles with data-driven methods, the materials science community can accelerate the discovery and development of next-generation catalysts to address pressing energy and environmental challenges.

In the pursuit of rational catalyst design, establishing a quantitative link between a material's electronic structure and its catalytic properties is paramount. For decades, the d-band center theory has served as a foundational electronic descriptor in heterogeneous catalysis, providing a powerful simplified model for predicting adsorption behavior on transition metal surfaces [10]. This theory posits that the weighted average energy of the d-orbital projected density of states (PDOS) relative to the Fermi level correlates strongly with adsorption strengths of reactants and intermediates [10]. However, with the advent of high-throughput computational screening and machine learning (ML) in materials science, researchers are increasingly looking beyond this single-parameter description toward the information-rich full electronic density of states (DOS) patterns to develop more accurate and universally applicable predictive models [11] [12].

This evolution from simplified descriptors to comprehensive electronic structure analysis represents a paradigm shift in computational catalysis. While the d-band center offers remarkable conceptual simplicity, its predictive power diminishes across diverse material classes and complex reaction environments [11]. Meanwhile, ML models capable of automatically extracting relevant features from the complete DOS spectrum have demonstrated superior accuracy for predicting catalytic properties such as adsorption energies across a wide range of surfaces and adsorbates [11]. This technical guide examines both traditional and emerging electronic descriptors within the context of machine learning-driven catalyst discovery, providing researchers with the theoretical foundation and practical methodologies needed to leverage these powerful tools in advanced materials design.

Fundamental Electronic Descriptors in Catalysis

The d-Band Center Theory and Its Applications

The d-band center theory, originally formalized by Professor Jens K. Nørskov, provides a fundamental framework for understanding adsorption behavior on transition metal surfaces [10]. The d-band center ($${\varepsilon_d}$$) is mathematically defined as the weighted average energy of the d-orbital projected density of states:

$$ {\varepsilond} = \frac{\int{-\infty}^{\infty} E \cdot \text{PDOS}d(E) dE}{\int{-\infty}^{\infty} \text{PDOS}_d(E) dE} $$

where $${\text{PDOS}_d(E)}$$ represents the projected density of states of the d-orbitals at energy level E [10]. The physical significance of this descriptor lies in its correlation with the strength of adsorbate-surface interactions: a higher d-band center (closer to the Fermi level) generally indicates stronger bonding due to enhanced hybridization between surface d-orbitals and adsorbate molecular orbitals, while a lower d-band center (further below the Fermi level) typically results in weaker interactions as anti-bonding states become increasingly populated [10].

The d-band center has been extensively generalized across various transition metal-based systems, including alloys, oxides, sulfides, and other complexes [10]. Its applications span crucial catalytic reactions such as the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), carbon dioxide reduction reaction (CO₂RR), nitrogen fixation, hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), and electrooxidation of polyhydroxy compounds [10]. Table 1 summarizes key applications of d-band center tuning in different catalytic systems.

Table 1: Applications of d-band Center Tuning in Catalysis

| Catalytic System | Application | Effect of d-band Center Tuning | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Alloys | Oxygen Evolution Reaction | Enhanced adsorption of oxygen intermediates | [10] |

| Sulfide Heterostructures | CO₂ Reduction | Optimized CO₂ adsorption and activation | [10] |

| Oxide Interfaces | Sodium Ion Batteries | Improved Na⁺ adsorption efficiency | [10] |

| Li-O₂ Battery Systems | Oxygen Electrochemistry | Optimized affinity to reaction intermediates | [10] |

Despite its widespread utility, the d-band center approach faces limitations when applied across diverse material spaces, as its predictive accuracy diminishes for complex surfaces and multi-element adsorbates [11]. This has motivated the development of more comprehensive electronic descriptors, including higher-order moments of the d-band (width, skewness, kurtosis) and ultimately the full DOS spectrum [11].

Full Density of States (DOS) as a Comprehensive Descriptor

The electronic density of states (DOS) represents the number of electronic states per unit volume per unit energy interval, providing a complete picture of a material's electronic structure [12]. Unlike single-value descriptors such as the d-band center, the DOS captures the intricate distribution of all electronic states across the energy spectrum, offering substantially more information for predicting chemical behavior [11] [12].

The fundamental advantage of full DOS patterns lies in their ability to capture complex electronic features that influence catalysis, including but not limited to: energy-dependent bonding and anti-bonding interactions, orbital-specific contributions to surface reactivity, filling of states near the Fermi level, and subtle electronic perturbations induced by alloying or strain effects [11] [12]. Consequently, materials with similar overall DOS patterns often exhibit comparable catalytic properties, even when their atomic compositions or crystal structures differ significantly [12].

DOS analysis has proven particularly valuable in explaining and predicting band gap engineering strategies, such as transition metal doping in semiconductor materials. For instance, DFT studies of Tl-doped α-Al₂O₃ demonstrated how metal insertion modifies the DOS distribution to reduce band gaps and enhance visible light absorption—critical properties for photocatalytic applications [13]. In such systems, analysis of both total DOS (TDOS) and partial DOS (PDOS) provides insights into specific orbital contributions to the modified electronic structure [13].

Machine Learning Approaches for Electronic Structure-Property Mapping

Learning from DOS Representations

Conventional machine learning applications in catalysis often rely on manually engineered features (e.g., d-band centers, coordination numbers) as model inputs [11]. However, this approach requires significant domain expertise and may overlook subtle but important electronic patterns. To address this limitation, researchers have developed specialized ML architectures that automatically extract relevant features directly from raw DOS data [11] [12].

DOSnet represents a pioneering approach in this domain, utilizing convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to process DOS inputs and predict adsorption energies [11]. The model accepts site- and orbital-projected DOS of surface atoms involved in chemisorption as separate input channels, enabling it to learn complex structure-property relationships without manual feature engineering [11]. When evaluated on a diverse dataset containing 37,000 adsorption energies across 2,000 unique bimetallic surfaces, DOSnet achieved a mean absolute error of approximately 0.1 eV—significantly outperforming models based solely on d-band centers [11].

For unsupervised learning tasks, DOS similarity descriptors offer powerful alternatives for materials clustering and discovery. These methods transform the DOS into compact numerical representations (fingerprints) that capture essential spectral features [12]. One advanced implementation employs a non-uniform energy discretization scheme that focuses resolution on strategically important regions (e.g., near the Fermi level), generating a binary-encoded 2D raster image that serves as a materials fingerprint [12]. The similarity between two materials can then be quantified using metrics such as the Tanimoto coefficient, enabling the identification of materials with analogous electronic characteristics across extensive databases [12].

Table 2: Machine Learning Models for Electronic Structure Analysis

| Model Name | Architecture | Input | Output | Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOSnet | Convolutional Neural Network | Orbital-projected DOS | Adsorption Energy | MAE: ~0.1 eV | [11] |

| dBandDiff | Diffusion Model | d-band center + Space group | Crystal Structure | 72.8% DFT-validated | [10] |

| PET-MAD-DOS | Transformer (Point Edge Transformer) | Atomic Structure | DOS | Variable by material class | [14] |

| DOS Fingerprint | Similarity Metric | DOS spectrum | Similarity Score | Enables clustering | [12] |

Inverse Design with Electronic Descriptors

Beyond property prediction, electronic descriptors are increasingly employed in generative models for inverse materials design. dBandDiff, a conditional generative diffusion model, exemplifies this approach by using target d-band center values and space group symmetry as inputs to generate novel crystal structures with desired electronic characteristics [10]. This methodology represents a significant departure from traditional screening approaches, directly addressing the combinatorial challenge of exploring vast materials spaces [10].

In practical demonstrations, dBandDiff successfully generated 1,000 structures across 50 space groups with targeted d-band centers ranging from -3 eV to 0 eV [10]. Subsequent DFT validation confirmed that 72.8% of these generated structures were physically reasonable, with most exhibiting d-band centers close to their target values [10]. This inverse design capability is particularly valuable for discovering catalysts optimized for specific reaction intermediates, as the d-band center can be strategically tuned to achieve optimal adsorption strengths [10].

Diagram 1: Inverse design workflow for catalyst discovery. The dBandDiff model uses target electronic properties and symmetry constraints to generate candidate structures, which are then validated through DFT calculations [10].

Computational Methods and Experimental Protocols

Density Functional Theory Calculations

Density Functional Theory (DFT) serves as the computational foundation for obtaining both d-band centers and DOS spectra [15]. DFT approaches the many-electron problem by using functionals of the spatially dependent electron density, effectively reducing the complex many-body Schrödinger equation to a more tractable single-body problem [15]. In practical catalysis research, DFT calculations are typically performed using software packages such as the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) with the Projector-Augmented Wave (PAW) method and Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functionals [10].

The standard workflow for calculating electronic descriptors involves several key stages, as visualized in Diagram 2. For surface catalysis studies, researchers typically: (1) build and optimize the bulk crystal structure; (2) cleave along specific crystallographic planes to create surface models; (3) perform geometry optimization of the clean surface; (4) compute the electronic structure through single-point calculations; and (5) extract the PDOS and total DOS for analysis [10] [15]. For the d-band center specifically, the PDOS of d-orbitals from surface atoms is numerically integrated according to the established formula to obtain the energy-weighted average [10].

Diagram 2: DFT workflow for electronic descriptor calculation. The process begins with bulk structure optimization and proceeds through surface modeling to final electronic analysis [10] [15].

DOS Fingerprinting Protocol

The transformation of raw DOS data into quantitative fingerprints enables similarity analysis and machine learning applications. The following protocol outlines the key steps for generating the advanced DOS fingerprint described in Section 3.1 [12]:

Energy Referencing: Shift the DOS spectrum so that ε = 0 aligns with a reference energy (εref), typically the Fermi level or another relevant electronic feature.

Non-uniform Discretization: Integrate the DOS ρ(ε) over Nε intervals of variable widths Δεi using the formula: $$ {\rhoi} = \int{{\varepsiloni}}^{{\varepsilon{i+1}}} \rho(\varepsilon) d\varepsilon $$ where the interval widths increase with distance from εref according to: $$ \Delta {\varepsiloni} = n({\varepsiloni}, W, N)\Delta {\varepsilon_{min}} $$ with ( n(\varepsilon, W, N) = \lfloor g(\varepsilon, W)N + 1 \rfloor ) and ( g(\varepsilon, W) = (1 - \exp(-\varepsilon^2/(2W^2))) ).

Histogram Transformation: Convert the integrated values into a 2D raster image by discretizing each column i into Nρ intervals of height Δρi, using a similar non-uniform scheme for the DOS axis.

Binary Encoding: Create a binary vector representation where each bit indicates whether the corresponding pixel in the raster image is "filled" based on the calculated ρi values.

This fingerprinting approach allows researchers to tailor the resolution to specific energy regions of interest, enhancing sensitivity to relevant electronic features while maintaining computational efficiency [12].

Table 3: Computational Tools and Databases for Electronic Descriptor Research

| Tool/Database | Type | Primary Function | Access | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VASP | Software Package | DFT Calculations | Commercial | Gold standard for DOS/PDOS calculation [10] |

| Materials Project | Database | Crystallographic & DFT Data | Free | Source of training data for ML models [10] |

| C2DB | Database | 2D Materials Properties | Free | DOS similarity analysis [12] |

| pymatgen | Python Library | Materials Analysis | Open Source | DOS processing and analysis [10] |

| Catalysis-Hub.org | Database | Surface Reaction Data | Free | Adsorption energies for validation [16] |

| IOChem-BD | Database | Computational Chemistry | Free | Storage and management of DFT results [16] |

The evolution from simplified descriptors like the d-band center to comprehensive DOS analysis represents significant progress in computational catalysis research. While the d-band center remains invaluable for providing intuitive chemical insights and facilitating rapid screening of transition metal systems, full DOS patterns coupled with machine learning offer unparalleled predictive accuracy across diverse materials spaces [10] [11]. The emerging paradigm of inverse design, exemplified by models like dBandDiff, further demonstrates how these electronic descriptors can actively drive the discovery of novel catalytic materials rather than merely explaining their behavior [10].

As machine learning methodologies continue to advance, the integration of electronic structure descriptors with other materials representations—including geometric, energetic, and compositional features—will likely yield increasingly sophisticated and predictive models [1]. Furthermore, the development of universal ML models capable of accurately predicting DOS directly from atomic structures promises to dramatically accelerate screening processes by bypassing costly DFT calculations [14]. These computational advances, combined with growing materials databases and improved experimental validation techniques, are establishing a comprehensive framework for the next generation of data-driven catalyst design.

The accelerated discovery of new functional materials, particularly catalysts, represents a critical challenge in addressing global energy and sustainability goals. Traditional experimental approaches, governed by trial-and-error, are often slow, resource-intensive, and limited in their ability to explore vast compositional and structural spaces. The emergence of high-throughput density functional theory (DFT) calculations has fundamentally shifted this paradigm, enabling the systematic computation of material properties at an unprecedented scale. This computational revolution has been coupled with the creation of large, publicly accessible databases that serve as repositories for this wealth of information, forming a core component of the modern materials data ecosystem [17].

Two pillars of this ecosystem are the Materials Project (MP) and the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD). These platforms provide researchers with immediate access to pre-computed quantum-mechanical data for hundreds of thousands of inorganic materials, drastically reducing the initial barrier for materials screening and design. The OQMD, for instance, has grown from its initial collection of nearly 300,000 DFT calculations to over one million compounds [17] [18]. When this vast data resource is integrated with machine learning (ML) methods, it creates a powerful, target-driven workflow for identifying promising candidate materials with specific desired properties, such as low work-function for catalytic applications [19]. This guide provides a technical overview of these databases, detailing their access, data structure, and integration into an ML-driven research pipeline for catalyst discovery.

Database Core Architectures and Data Provenance

A foundational understanding of the data generation methodologies and core architectures of MP and OQMD is essential for researchers to correctly interpret and utilize the contained properties.

The Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD)

The OQMD is a high-throughput database built on a decentralized framework called qmpy, a Python package that uses a Django web framework as an interface to a MySQL database. The database's contents are derived from DFT total energy calculations performed in a consistent manner to ensure comparability across different material classes [17].

- Data Sources and Contents: The structures in the OQMD originate from two primary sources. The first is experimental crystal structures obtained from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). The second is a large set of hypothetical compounds based on decorations of commonly occurring crystal structure prototypes (e.g., perovskite, spinel). This combination provides a mix of experimentally realized and predicted structures, enabling the assessment of phase stability and the prediction of new, previously unsynthesized compounds [17].

- Calculation Methodology: The OQMD employs the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP) with the PAW-PBE potentials. The settings are optimized for efficiency within a constrained standard of convergence, using a consistent plane-wave cutoff, smearing schemes, and k-point densities across all calculations to allow for direct comparison of energies between different compounds. The database also includes DFT+U calculations for certain elements to better describe strongly correlated electrons [17].

The Materials Project (MP)

The Materials Project also provides a vast repository of computed materials information, built using a suite of open-source software libraries including pymatgen [20].

- Data Aggregation and Versioning: A critical aspect of the Materials Project is its structured approach to data updates. The MP database undergoes periodic versioned releases (e.g., v2025.09.25, v2025.04.10). Each release can include new content, corrections to existing data, and changes to the underlying data aggregation methods. For example, recent versions have introduced materials calculated with the more advanced r2SCAN functional and have migrated schema for phonon data [21]. This versioning system ensures reproducibility, as researchers can cite the specific database version from which their data was retrieved [20] [21].

- Material and Task Identifiers: The MP uses two key identifiers. A

task_id(e.g.,mp-123456) refers to an individual, immutable calculation. Amaterial_idis assigned to a unique material (polymorph) and aggregates data from multiple underlying tasks. Thematerial_idis typically the numerically smallesttask_idassociated with that material [20].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of OQMD and the Materials Project

| Feature | Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) | Materials Project (MP) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Access Method | RESTful API (/oqmdapi/formationenergy), qmpy Python API, web interface [22] |

RESTful API (via mp-api Python client), web interface [23] |

| Data Provenance | ICSD structures & hypothetical prototype decorations [17] | ICSD structures, contributed datasets (e.g., GNoME), and others |

| Calculation Method | VASP, PAW-PBE, consistent k-point density, DFT+U [17] | VASP, PBE, GGA+U, increasingly r2SCAN [20] [21] |

| Key Identifier | entry_id [22] |

material_id (mp-id), task_id [20] |

| Update Policy | Project-based growth [18] | Versioned releases (e.g., v2025.09.25) [21] |

Technical Protocols for Data Extraction via APIs

Programmatic access is the most powerful method for extracting data for high-throughput analysis and ML model training. Both databases offer robust API interfaces.

Querying the OQMD API

The OQMD's RESTful API allows for flexible querying of its formation energy dataset. The base URL for queries is http://oqmd.org/oqmdapi/formationenergy [22].

- URL Structure and Key Parameters: Queries are constructed by specifying parameters after the base URL.

fields: Determines which properties are returned (e.g.,name, entry_id, spacegroup, band_gap, delta_e).filter: Applies logical filters to the data using a custom syntax (e.g.,filter=element_set=(Al-Fe),O AND band_gap>1.0).limit/offset: Controls pagination for managing large result sets.sort_by: Sorts results by a specific property, such asdelta_e(formation energy) [22].

- Available Keywords: A wide range of properties are available for filtering and output. Key properties for stability analysis include

delta_e(formation energy),stability(hull distance),band_gap,spacegroup, andntypes(number of element types). Theelement_setkeyword is particularly useful for filtering compositions [22].

Table 2: Key OQMD API Parameters for Catalyst Screening [22]

| Parameter | Function | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

filter |

Applies logical conditions to the search. | filter=element_set=Mn,O AND stability<0.05 AND band_gap=0 |

fields |

Selects specific properties in the output. | fields=name,entry_id,delta_e,band_gap,volume |

stability |

Returns compounds with a specified distance from the convex hull. | filter=stability=0 (thermodynamically stable) |

element_set |

Filters compounds containing specific elements. | filter=element_set=(Co-Fe),O (Co/Fe AND O) |

ntypes |

Filters by the number of distinct elements. | filter=ntypes=3 (ternary compounds) |

sort_by |

Orders results by a property (e.g., formation energy). | sort_by=delta_e&desc=True |

Example OQMD API Query in Python:

The qmpy_rester Python wrapper simplifies interaction with the OQMD API. The following example demonstrates a search for stable, ternary oxides containing cobalt or iron.

Accessing the Materials Project API

The Materials Project provides data access through its officially supported Python client, mp-api [23].

- Authentication: Using the MP API requires creating an account at the Materials Project website and generating an API key.

- Data Retrieval with MPRester: The primary interface for data access is the

MPResterclass. Thesummaryendpoint is often the most efficient way to retrieve a broad set of material properties for analysis.

Example MP API Query in Python:

Integrated Workflow for ML-Guided Catalyst Discovery

The true power of these databases is realized when they are integrated into a target-driven discovery pipeline. The following workflow, inspired by successful applications in discovering low-work-function perovskites, outlines the key stages from data acquisition to experimental validation [19].

Diagram 1: ML-Guided materials discovery workflow. The process integrates high-throughput database querying, machine learning, and first-principles validation.

Workflow Stage 1: Data Acquisition and Curation

The initial stage involves using the APIs described in Section 3 to build a dataset for training a machine learning model.

- Property Selection: For catalyst discovery, key properties extracted might include:

- Stability Metrics:

energy_above_hull(MP) orstability(OQMD) to ensure synthesizability. - Electronic Properties:

band_gapto distinguish metals from insulators. - Surface Properties: Work function, which may need to be calculated from the bulk structure or retrieved from specialized datasets.

- Compositional & Structural Features: Formula, space group, number of atoms, and volume [22] [20].

- Stability Metrics:

- Data Cleaning: The retrieved data must be cleaned and standardized. This involves handling missing values, ensuring consistency in units, and removing duplicates or entries flagged with calculation errors.

Workflow Stage 2: Feature Engineering and Model Training

With a curated dataset, the next step is to convert material structures into numerical features (descriptors) that an ML algorithm can process.

- Common Descriptors:

- Compositional Features: Elemental fractions, statistical properties of atomic number, electronegativity, etc.

- Structural Features: Space group number, density, coordination numbers, and Voronoi tessellation-based features.

- Model Training: A regression model (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, or Neural Network) is trained on the featurized dataset to learn the mapping between the material descriptors and the target property (e.g., work function) [19].

Workflow Stage 3: Screening and Validation

The trained ML model is used to predict the target property for a vast space of hypothetical or known compounds not present in the original database. For instance, the model could screen thousands of A₂BB'O₆-type double perovskite compositions [19].

- High-Throughput ML Screening: The ML model rapidly evaluates the entire chemical space, producing a ranked list of promising candidates with predicted properties.

- High-Precision DFT Validation: The top candidates from the ML screen are then validated using more accurate and computationally expensive DFT calculations. This step confirms the stability and property predictions from the ML model, as highlighted in the case study where 27 stable perovskites were identified from an initial pool of 23,822 candidates [19].

- Feedback Loop: The results of the DFT validation can be fed back into the training dataset, improving the accuracy of the ML model for future iterations—a key aspect of active learning.

Case Study: Discovery of Low-Work-Function Perovskites

A recent study exemplifies the successful application of this integrated workflow for the discovery of stable, low-work-function perovskite oxides for catalysis and energy technologies [19].

- Objective: Identify stable ABO₃-type single and A₂BB'O₆-type double perovskite oxides with work functions of AO-terminated (001) surfaces below 2.5 eV.

- Implementation:

- An ML model was trained on data from materials databases to predict work function and stability.

- The model screened 23,822 candidate materials.

- High-precision DFT calculations validated the ML predictions, narrowing the list to 27 stable perovskite oxides.

- Experimental Outcome: Two of the top predicted compounds, Ba₂TiWO₈ and Ba₂FeMoO₆, were successfully synthesized. Ba₂TiWO₈ showed promise for catalytic NH₃ synthesis and decomposition, while Ba₂FeMoO₆ exhibited exceptional long-term cycling stability as a Li-ion battery electrode, demonstrating over 10,000 cycles at a high current density [19]. This underscores the potential of the approach to discover multifunctional materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Catalysis

| Tool / Resource | Function / Purpose | Relevance to Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| OQMD RESTful API | Programmatic access to query formation energies, stability, and electronic structure data for ~1M compounds [22] [18]. | Data acquisition for initial training set and validation. |

Materials Project mp-api |

Official Python client for accessing the MP database, providing aggregated material data and specific task documents [23]. | Data acquisition, retrieval of crystal structures (CIF files) and properties. |

| VASP (Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package) | High-precision DFT software used for calculating total energies and electronic properties from first principles [17]. | Final validation of candidate materials' stability and properties. |

| Pymatgen | Python library for materials analysis, providing robust support for crystal structures, phase diagrams, and file I/O (e.g., CIF, POSCAR) [17]. | Featurization of materials, structural analysis, and file format handling. |

| ML Library (e.g., Scikit-learn) | Provides a unified interface for a wide range of machine learning algorithms for regression and classification. | Training the predictive model for target property estimation. |

The Materials Project and OQMD have established themselves as indispensable infrastructure in the materials science landscape. They provide the foundational data upon which predictive models are built. As demonstrated by the successful discovery of novel perovskite catalysts, the integration of these databases with machine learning and high-fidelity validation calculations creates a powerful, accelerated pipeline for functional materials design. This synergistic approach, which efficiently traverses from vast chemical spaces to a focused set of experimentally viable candidates, is poised to remain at the forefront of catalytic and energy materials discovery.

From Code to Catalyst: High-Throughput Workflows and Real-World Applications

The discovery of high-performance catalysts is pivotal for advancing sustainable chemical processes, yet it is often hampered by the high cost and scarcity of noble metals. Palladium (Pd) is a prototypical catalyst for numerous reactions, including the direct synthesis of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), but its widespread application is constrained by economic and supply-chain considerations [24]. The exploration of bimetallic alloys to replace or reduce Pd usage presents a vast combinatorial challenge, making traditional experimental approaches time-consuming and resource-intensive.

High-throughput computational screening, particularly when integrated with machine learning (ML), has emerged as a powerful paradigm to accelerate materials discovery. This guide details a proven protocol for the discovery of bimetallic Pd-replacement catalysts, using electronic structure similarity as a core descriptor. The methodology is presented within the broader context of modern catalysis informatics, demonstrating how computational and ML-driven workflows can efficiently navigate complex materials spaces to identify promising candidates for experimental validation [24] [25].

High-Throughput Screening Protocol: A Pd Replacement Case Study

Core Screening Descriptor: Electronic Density of States Similarity

A critical innovation in this screening protocol is the use of the full electronic Density of States (DOS) pattern as a primary descriptor. The foundational hypothesis is that bimetallic alloys with DOS patterns similar to Pd will exhibit catalytic properties comparable to Pd [24].

- Theoretical Basis: The electronic DOS, particularly near the Fermi level, determines the surface reactivity and adsorption characteristics of a catalyst. While classical descriptors like the d-band center are valuable, the full DOS pattern incorporates comprehensive information from both d-states and sp-states, providing a more complete picture of surface electronic structure [24].

Quantitative Similarity Metric: The similarity between the DOS of a candidate alloy and the reference Pd(111) surface is quantified using the following metric:

( \Delta DOS{2-1} = \left{ {\int} {\left[ {DOS2\left( E \right) - DOS_1\left( E \right)} \right]^2} {g}\left( {E;\sigma} \right){d}E \right}^{\frac{1}{2}} )

where ( g(E;\sigma) ) is a Gaussian distribution function centered at the Fermi energy ((E_F)) with a standard deviation ( \sigma = 7 ) eV. This function assigns higher weight to the electronic states near the Fermi level, which are most critical for catalytic bonding [24].

Table 1: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for High-Throughput Screening

| Item Name | Function/Role in the Screening Workflow |

|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | First-principles calculation of formation energies and electronic Density of States (DOS) for candidate structures [24]. |

| Transition Metal Elements (30) | Building blocks from periods IV, V, and VI for constructing binary alloy systems [24]. |

| Crystal Structure Prototypes (10) | Underlying templates (B1, B2, L10, etc.) for generating initial 1:1 bimetallic alloy models [24]. |

| DOS Similarity (( \Delta DOS )) | Key quantitative descriptor for predicting catalytic similarity to the Pd reference material [24]. |

| Formation Energy (( \Delta E_f )) | Thermodynamic metric for assessing the stability and synthetic feasibility of bimetallic alloys [24]. |

The screening protocol follows a staged funnel to efficiently narrow down candidates from thousands to a handful for experimental testing. The overall workflow is designed to sequentially evaluate thermodynamic stability, electronic similarity, and synthetic feasibility [24].

Detailed Experimental and Computational Methodologies

High-Throughput DFT Calculations

The initial computational phase involved several key steps to generate and evaluate a large library of potential candidates.

- Search Space Definition: The study considered 435 binary systems (from 30 transition metals) with a 1:1 composition. For each binary pair, ten ordered crystal structures (B1, B2, B3, B4, B11, B19, B27, B33, L10, L11) were investigated, resulting in a total of 4,350 initial candidate structures [24].

- Thermodynamic Stability Screening: The formation energy (( \Delta Ef )) of each structure was calculated using DFT. A threshold of ( \Delta Ef < 0.1 ) eV was applied to filter for thermodynamically stable or metastable alloys, resulting in 249 candidates. This margin accounts for the potential stabilization of non-equilibrium phases via nanosize effects [24].

- DOS Pattern Calculation and Comparison: For the 249 thermodynamically screened alloys, the DOS was projected onto the close-packed surface atoms. The similarity to the Pd(111) surface DOS was then calculated using the ( \Delta DOS ) metric. Seventeen candidates with ( \Delta DOS < 2.0 ) were identified as having high electronic similarity to Pd [24].

The Role of sp-States in Descriptor Performance

A critical finding was the significant role of sp-states, in addition to d-states, in determining catalytic properties for the target reaction (H₂O₂ direct synthesis). Analysis of O₂ adsorption on a Ni₅₀Pt₅₀(111) surface showed negligible change in the d-band DOS after adsorption, while the sp-band DOS patterns changed more smoothly. This indicates that the O₂ molecule interacts more strongly with the sp-states of the surface atoms, highlighting the necessity of including the full DOS (d- and sp-states) in the descriptor for an accurate prediction [24].

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

The final eight candidate alloys selected from computational screening were synthesized and tested for H₂O₂ direct synthesis.

- Validation Results: Four of the eight candidates (Ni₆₁Pt₃₉, Au₅₁Pd₄₉, Pt₅₂Pd₄₈, and Pd₅₂Ni₄₈) exhibited catalytic performance comparable to pure Pd. Notably, the Pd-free Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ catalyst outperformed the prototypical Pd catalyst and demonstrated a 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity due to its high content of inexpensive Ni [24].

Table 2: Screening Results and Experimental Validation for Selected Catalysts [24]

| Bimetallic Catalyst | Crystal Structure | ΔDOS (Similarity to Pd) | Experimental Catalytic Performance | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ | N/A | Low (Value not specified) | Comparable to Pd, 9.5x cost-normalized productivity | High-performance, Pd-free catalyst [24] |

| Au₅₁Pd₄₉ | N/A | Low (Value not specified) | Comparable to Pd | Validated replacement [24] |

| Pt₅₂Pd₄₈ | N/A | Low (Value not specified) | Comparable to Pd | Validated replacement [24] |

| Pd₅₂Ni₄₈ | N/A | Low (Value not specified) | Comparable to Pd | Validated replacement [24] |

| CrRh | B2 | 1.97 | Not specified in results | Promising electronic similarity [24] |

| FeCo | B2 | 1.63 | Not specified in results | Promising electronic similarity [24] |

Integration with Machine Learning for Enhanced Catalyst Discovery

The described high-throughput screening protocol provides a robust foundation that can be significantly augmented by machine learning. ML techniques address key limitations, such as the computational expense of DFT, and enable the identification of complex, non-intuitive structure-property relationships [26] [25].

Machine Learning Models and Descriptors in Catalysis

ML models can predict catalytic properties like adsorption energies directly, bypassing the need for exhaustive DFT calculations in initial screening rounds.

- Descriptor Development and Feature Minimization: A key challenge is identifying a small set of powerful, generalizable descriptors. One recent study achieved high predictive accuracy (R² = 0.922) for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) using an Extremely Randomized Trees model with only ten features. This included a key energy-related feature, ( \varphi = {Nd0}^{2}/{\psi 0} ), which strongly correlates with HER free energy (( \Delta G_H )) [26].

- Broad Applicability Across Catalyst Types: Advanced ML models are now being trained on diverse datasets encompassing various catalyst types (pure metals, intermetallic compounds, perovskites, etc.). This allows for a single model to screen a much wider range of materials than would be feasible with facet-specific traditional descriptors [26].

Emerging Workflows: ML-Accelerated Screening

Novel workflows are merging ML force fields (MLFFs) with sophisticated descriptors for rapid and accurate screening.

- Adsorption Energy Distributions (AEDs): A recent approach for CO₂-to-methanol catalysts introduced AEDs as a versatile descriptor. Instead of a single adsorption energy, an AED aggregates binding energies across different catalyst facets, binding sites, and adsorbates, providing a more holistic "fingerprint" of a catalyst's energetic landscape [2].

- Workflow Efficiency: Pre-trained MLFFs, such as those from the Open Catalyst Project, can compute adsorption energies with DFT accuracy but at a speedup of 10,000 times or more. This enables the generation of massive AED datasets (e.g., over 877,000 adsorption energies across 160 materials) that form the basis for ML-driven discovery [2].

- Similarity Analysis: Once AEDs are generated, unsupervised ML techniques, such as hierarchical clustering using the Wasserstein distance metric, can group catalysts with similar AED profiles. This allows researchers to propose new candidates based on their similarity to known high-performing catalysts [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The experimental execution of high-throughput screening relies on a suite of computational and data resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Catalyst Screening

| Tool/Resource Name | Function in the Research Workflow |

|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | First-principles calculation of formation energies, electronic structures, and adsorption energies [24] [25]. |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) | High-speed, quantum-mechanically accurate calculation of adsorption energies and relaxation of surface-adsorbate structures [2]. |

| Materials Project Database | Open-access database of known and computed crystal structures and properties for initial candidate generation [2]. |

| Catalysis-Hub.org | Specialized database for reaction and activation energies on catalytic surfaces, used for ML model training [26] [25]. |

| Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) | Python module used for setting up, running, and analyzing atomistic simulations [26] [25]. |

| Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen) | Open-source Python library for materials analysis, useful for feature extraction and high-throughput workflows [25]. |

The case study on replacing palladium in bimetallic catalysts demonstrates the power of high-throughput computational screening driven by physically insightful descriptors. The use of full DOS similarity successfully bridged computation and experiment, leading to the discovery of high-performance, cost-effective catalysts like Ni₆₁Pt₃₉. The ongoing integration of machine learning is poised to further revolutionize this field. By developing minimal, powerful feature sets and leveraging ML force fields for rapid energy calculations, researchers can navigate the vast compositional and structural space of potential catalysts with unprecedented speed and accuracy. This combined computational-ML paradigm provides a robust and generalizable framework for the future discovery of advanced catalytic materials.

The integration of artificial intelligence with robotic experimentation is revolutionizing materials science, dramatically accelerating the discovery of novel functional materials. This technical guide examines the core architecture, experimental methodologies, and performance metrics of the CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists) platform, an advanced AI-driven system for autonomous materials exploration. Framed within a broader research initiative on machine learning-driven catalyst discovery, we detail how CRESt's multimodal learning approach and closed-loop experimentation have achieved record-setting performance in fuel cell catalyst development through the systematic investigation of over 900 material chemistries and 3,500 electrochemical tests. The platform represents a paradigm shift toward self-driving laboratories that seamlessly integrate human scientific intuition with robotic precision and AI-driven optimization.

Traditional materials discovery relies heavily on trial-and-error approaches that are often time-consuming, expensive, and limited in their ability to navigate complex parameter spaces. The emergence of data-driven methodologies has transformed this landscape, enabling researchers to rapidly identify promising material candidates through computational prediction and automated validation [27]. This paradigm shift is particularly impactful in catalyst research, where the combinatorial complexity of multi-element systems presents significant challenges for conventional approaches.

AI-driven robotic platforms address these limitations through closed-loop optimization systems that integrate computational design, automated synthesis, and performance characterization in a continuous feedback cycle. These systems leverage multiple AI methodologies, including Bayesian optimization for experimental planning, large language models for literature mining and knowledge integration, and computer vision for real-time experimental monitoring and quality control [28] [29]. The CRESt platform represents a state-of-the-art implementation of these capabilities, specifically designed to accelerate the discovery of advanced catalytic materials for energy applications.

The CRESt Platform: Architectural Framework

Core System Components

The CRESt platform employs a multimodal architecture that integrates diverse data sources and experimental capabilities into a unified discovery workflow [28]. As illustrated in Figure 1, the system coordinates multiple specialized modules to enable end-to-end autonomous materials investigation.

Figure 1: Core workflow of the CRESt platform showing the integration of knowledge extraction, AI planning, robotic execution, and continuous learning.

The platform's hardware infrastructure includes a comprehensive suite of automated laboratory equipment:

- Liquid-handling robots for precise reagent manipulation and solution preparation

- Carbothermal shock systems for rapid materials synthesis

- Automated electrochemical workstations for high-throughput performance testing

- Characterization equipment including automated electron microscopy and optical microscopy

- Ancillary devices including pumps, gas valves, and environmental control systems that can be remotely operated [28]

This hardware ensemble enables the platform to execute complex experimental protocols with minimal human intervention while maintaining precise control over synthesis parameters and processing conditions.

Multimodal AI and Knowledge Integration

CRESt's analytical core employs a sophisticated AI framework that transcends conventional single-data-stream approaches by integrating diverse information sources:

- Scientific literature analysis using transformer models to extract synthesis methodologies and structure-property relationships from text and data repositories

- Experimental data streams including chemical compositions, microstructural images, crystallographic information, and performance metrics

- Human feedback incorporating researcher intuition, observational insights, and strategic guidance through natural language interfaces [28]

This multimodal approach enables the system to build comprehensive material representations that embed prior knowledge before experimentation begins. The platform employs principal component analysis in this knowledge-embedding space to identify reduced search regions that capture most performance variability, significantly enhancing the efficiency of subsequent optimization cycles [28].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Catalyst Discovery Workflow for Fuel Cell Applications

The CRESt platform implements a structured, iterative workflow for catalyst discovery and optimization, specifically applied to direct formate fuel cell catalysts in the referenced study [28]. The methodology proceeds through five key phases:

Figure 2: Five-phase experimental workflow for autonomous catalyst discovery implemented in the CRESt platform.

Phase 1: Knowledge-Based Initialization The process begins with the literature mining module analyzing scientific publications and materials databases to identify promising element combinations and synthesis approaches. For fuel cell catalyst research, this includes retrieving information on palladium behavior in electrochemical environments, historical performance data on precious metal catalysts, and documented synthesis protocols for multielement nanomaterials [28]. The system constructs an initial knowledge-embedded representation of the potential search space encompassing up to 20 precursor molecules and substrates.

Phase 2: Robotic Synthesis The liquid-handling robot prepares material libraries according to formulations determined by the AI planning module. The platform employs a carbothermal shock system for rapid synthesis, enabling rapid thermal processing of catalyst precursors. This system can precisely control heating rates, maximum temperatures, and dwell times to manipulate nucleation and growth processes [28]. The robotic arms coordinate material transfer between synthesis stations, purification modules, and characterization instruments.

Phase 3: High-Throughput Characterization Synthesized materials undergo automated structural and morphological analysis through scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, and optical microscopy [28]. Computer vision algorithms process the resulting images to assess particle size distributions, morphological features, and structural defects. This quantitative microstructural data is integrated with composition information to build structure-property relationships.