Physisorption and Chemisorption Measurement Methods: A Guide for Material and Pharmaceutical Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the measurement methods for physisorption and chemisorption, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and material science.

Physisorption and Chemisorption Measurement Methods: A Guide for Material and Pharmaceutical Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the measurement methods for physisorption and chemisorption, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and material science. It covers the foundational principles distinguishing these adsorption processes, details core analytical techniques like BET and temperature-programmed methods, and offers practical insights for troubleshooting and optimizing experiments. A comparative framework is also provided to validate data and select the most appropriate method for specific applications, from catalyst development to pharmaceutical characterization.

Physisorption vs. Chemisorption: Understanding Core Principles and Energetics

Molecular adsorption on solid surfaces is a fundamental process in surface science, underpinning numerous applications in heterogeneous catalysis, gas storage, sensor technology, and drug development [1] [2]. This process occurs through two primary mechanisms: physisorption (physical adsorption), dominated by van der Waals forces, and chemisorption (chemical adsorption), characterized by the formation of chemical bonds [1] [3]. Accurately distinguishing between these processes is crucial for designing materials with tailored surface properties, as the mechanism directly influences the strength, stability, and reversibility of the adsorbate-substrate interaction [1]. For researchers and scientists, selecting the appropriate measurement technique is paramount for correctly interpreting adsorption data and optimizing processes, from catalyst design to pharmaceutical development. This application note provides a structured comparison of these adsorption processes and details the experimental protocols for their characterization.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Analysis

Physisorption: Van der Waals Interactions

Physisorption results from weak, long-range van der Waals forces between the adsorbate molecule and the substrate surface [3]. These forces originate from interactions between induced, permanent, or transient electric dipoles, and the electronic structure of the adsorbate is barely perturbed upon adsorption [3]. The interaction energy is typically very weak, on the order of 10–100 meV (approximately 1–10 kJ/mol) [3]. A key characteristic of physisorption is that it is non-specific and can occur on any surface, provided the temperature and pressure conditions are favorable [1]. It is also reversible, and the adsorbed molecules can be easily removed by evacuation at the adsorption temperature or by mild heating [1]. Furthermore, because it does not require direct contact with specific surface sites, physisorption can proceed to form multiple layers of adsorbate [1].

Chemisorption: Chemical Bond Formation

Chemisorption involves the formation of a chemical bond between the adsorbate and specific locations on the material's surface, known as active sites [1] [4]. This process often involves significant sharing of electrons between the adsorbate and the surface, which alters the electronic structure of both and can dissociate the adsorbate [5] [1]. The binding energies are much stronger, typically in the range of 1-10 eV (approximately 100–1000 kJ/mol) [5]. Unlike physisorption, chemisorption is specific to certain adsorbent-adsorptive pairs and only occurs on clean active sites [1] [4]. It is also largely irreversible under mild conditions; removing chemically adsorbed molecules requires a substantial influx of energy, often involving very high temperatures [1]. Finally, because it requires direct contact with an active site, chemisorption is inherently a single-layer process [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Physisorption and Chemisorption

| Characteristic | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Interaction Force | Van der Waals forces [3] | Chemical bonding (covalent/ionic) [1] |

| Binding Energy | Weak (~10–100 meV) [3] | Strong (~1–10 eV) [5] |

| Reversibility | Easily reversible [1] | Largely irreversible [1] |

| Specificity | Non-specific [1] | Highly specific [1] |

| Process Nature | Multi-layer possible [1] | Single-layer only [1] |

| Temperature Dependence | Occurs at low temperatures [1] | Can occur at high temperatures [1] |

Interplay and Intermediate Mechanisms

In practical systems, the distinction between physisorption and chemisorption is not always absolute. Intermediate mechanisms can exist, such as Kubas interactions, which are often observed in hydrogen storage research. These interactions involve side-on coordination of H2 molecules to transition metal centers, featuring both donation of σ-electron density from H2 to the metal and back-donation of electron density from the metal d-orbitals to the σ*-antibonding orbital of H2 [5]. This results in adsorption energies that bridge the gap between pure physisorption and chemisorption (e.g., -0.42 to -0.53 eV/H2), enabling reversible hydrogen storage at near-ambient conditions [5]. Furthermore, the adsorption mechanism can change with temperature. For instance, on Sc-decorated BeN4, hydrogen molecules can be adsorbed reversibly via Kubas interactions at room temperature, but they dissociate into isolated H-atoms bound by pure chemisorption at elevated temperatures (500 K), leading to irreversible storage [5].

Table 2: Experimental Data from Selected Adsorption Systems

| Material System | Adsorbate | Interaction Type | Adsorption Energy | Gravimetric Capacity | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine BeN4 | H₂ | Physisorption | -0.12 eV/H₂ | ~1.3 wt% (at 100 K) | [5] |

| Sc-decorated BeN4 | H₂ | Kubas Interaction | -0.42 to -0.53 eV/H₂ | 7.86 wt% (at 300 K) | [5] |

| Sc-decorated BeN4 (500 K) | H (atoms) | Chemisorption | N/A | 6.0 wt% (at 400 K) | [5] |

| Silica-coated LSPR Sensor | Human Serum Albumin | Physisorption (Electrostatic) | N/A | N/A | [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Differentiation

A range of analytical techniques is available to characterize adsorption processes, each providing insights into the quantity adsorbed, binding strength, and nature of the surface interaction.

Volumetric (Static) Chemisorption/Physisorption Analysis

The volumetric method is a powerful technique for obtaining high-resolution adsorption isotherms, which are plots of the quantity of gas adsorbed versus pressure at a constant temperature [1] [7].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: The solid sample is placed in a known volume and subjected to in-situ pretreatment (e.g., degassing, heating, or reduction) under vacuum to clean the surface of any contaminants [7].

- First Isotherm Measurement: A precise amount of analys gas (e.g., H2, CO, N2) is dosed sequentially into the sample cell. After each dose, the system is allowed to reach equilibrium, and the pressure is measured. The quantity adsorbed is calculated from the pressure drop using the known system volume [7]. This first isotherm represents the sum of both chemisorption and physisorption [7].

- Evacuation: The sample is evacuated to remove the loosely bound, physisorbed molecules. The strongly bound, chemisorbed molecules remain on the surface, blocking the active sites [7].

- Second Isotherm Measurement: The adsorption isotherm is measured again on the now partially saturated sample. This second isotherm represents only the physisorption component [7].

- Data Analysis: The pure chemisorption isotherm is obtained by subtracting the second isotherm (physisorption) from the first isotherm (total adsorption). From this, the active surface area, metal dispersion, and energy distribution of sites can be derived [7].

Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD)

TPD is a dynamic technique used to probe the strength, number, and heterogeneity of chemisorption sites by monitoring desorption as a function of temperature [1] [7].

Protocol:

- Adsorption and Saturation: The pretreated sample is exposed to the probe gas (e.g., NH3 for acid sites, H2 for metal sites) until the active sites are saturated [1] [7].

- Purging: An inert gas (e.g., He, Ar) is flowed over the sample to flush out any remaining physisorbed molecules from the gas phase [1] [7].

- Controlled Heating: The sample temperature is increased linearly at a controlled rate (e.g., 10 °C/min) under a continuous flow of inert gas [1].

- Detection: A Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) monitors the gas stream. As the temperature overcomes the binding energy of the adsorbed molecules, they desorb, causing a change in the thermal conductivity of the gas stream, which is recorded as a peak [1] [7].

- Data Analysis: The temperature of the desorption peak(s) indicates the strength of the binding sites (higher temperature = stronger binding). The area under the peak is proportional to the number of sites of that strength [1]. Activation energies for desorption can be calculated from the peak shapes and positions [1].

Complementary Techniques

Other essential techniques for studying adsorption include:

- Pulse Chemisorption: A dynamic method where small, repeated pulses of probe gas are injected into an inert carrier gas flowing over the sample. A TCD detects the amount of gas adsorbed until saturation is reached. This is a rapid technique for determining active metal surface area and dispersion, primarily probing the strongest active sites [1] [4].

- Computational Methods (DFT): Density Functional Theory simulations, especially those corrected for van der Waals interactions (DFT-D2, DFT-D3, rVV10), are used to investigate interaction mechanisms at the atomic level. They can calculate adsorption energies, electronic structure changes, and identify the nature of the bond, helping to interpret experimental data [5] [2].

- Gas Chromatography (GC): Used for quantitative analysis of adsorbed species, particularly in applications like VOC capture. The adsorbent is exposed to a vapor, and the amount adsorbed/desorbed is quantified by GC, allowing for the study of reversibility and capacity [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and reagents commonly used in adsorption experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Adsorption Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Gases | Used to titrate and characterize specific active sites on a material. | H₂: For metal surface area and dispersion [7] [4]. CO: For titrating surface metal atoms [4]. O₂: For oxidative sites and metal dispersion [4]. NH₃: For quantifying acid site strength and concentration [7]. |

| Inert Carrier Gases | Used to create an inert atmosphere and carry probe gases in dynamic methods. | He, Ar, N₂: Must be high-purity to avoid contaminating the sample surface [7]. |

| Supported Catalysts | Common materials for studying chemisorption in heterogeneous catalysis. | e.g., Pt/Al₂O₃, Pd/SiO₂. The support provides a high surface area for dispersing the active metal [1]. |

| Porous Materials | Used for physisorption studies and gas storage; their high surface area is ideal for measuring BET surface area and pore size distribution. | Zeolites: For VOC adsorption and acid-site studies [8]. Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): For high-capacity gas storage [5]. |

| 2D Nanomaterials | Model systems and advanced materials for studying both physisorption and metal-functionalized chemisorption. | Graphene, BeN₄: Pristine versions study physisorption; metal-decorated (e.g., Sc, Li) versions study enhanced and Kubas-type adsorption for hydrogen storage [5]. |

| Dielectric-Coated Sensor Chips | Used in label-free biosensing (e.g., LSPR) to study protein adsorption and conformational changes on different surfaces. | SiO₂-, TiO₂-coated chips: Allow for the study of biointerfacial interactions under varying physiological conditions [6]. |

The clear distinction between physisorption and chemisorption, grounded in the fundamental forces involved—van der Waals versus chemical bonds—is critical for advancing research in catalysis, materials science, and drug development. The choice of characterization technique, whether volumetric analysis for precise isotherm measurement, TPD for site strength distribution, or pulse chemisorption for rapid dispersion analysis, must align with the specific adsorption mechanism under investigation. By applying the protocols and utilizing the tools outlined in this note, researchers can accurately deconvolute these complex surface processes, enabling the rational design of next-generation adsorbents and catalytic materials.

The accumulation of molecular species on a solid surface, a process known as adsorption, is a fundamental phenomenon in heterogeneous catalysis, gas separation, and drug development. Adsorption processes are primarily categorized into physisorption (physical adsorption) and chemisorption (chemical adsorption), which are critically distinguished by three key factors: the enthalpy of adsorption, the reversibility of the process, and the specificity for particular surface sites. Understanding these differentiating factors is essential for selecting appropriate characterization methods, designing efficient catalytic systems, and developing targeted drug delivery mechanisms. Physisorption occurs when adsorbate molecules are held to the adsorbent surface by weak van der Waals forces, resulting in low adsorption enthalpy and non-specific, reversible binding. In contrast, chemisorption involves the formation of chemical bonds between the adsorbate and specific active sites on the adsorbent surface, characterized by significantly higher adsorption enthalpy and typically irreversible behavior under standard conditions. This application note details the core differentiating factors between these adsorption processes and provides standardized protocols for their experimental characterization.

Core Differentiating Factors

The fundamental differences between physisorption and chemisorption are quantitatively defined by their enthalpy changes, reversibility characteristics, and specificity. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these key parameters.

Table 1: Key Differentiating Factors Between Physisorption and Chemisorption

| Factor | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Enthalpy of Adsorption | Low (20-40 kJ/mol) [9] | High (80-240 kJ/mol) [9] |

| Nature of Interaction | Van der Waals forces [9] | Chemical bonds [9] |

| Reversibility | Reversible [9] | Irreversible [9] |

| Specificity | Non-specific [9] | Highly specific [9] |

| Temperature Dependence | Favors low temperature, decreases with increasing temperature [9] | Favors high temperature, increases with increasing temperature [9] |

| Layer Formation | Multimolecular layers [9] | Unimolecular layer [9] |

| Activation Energy | Low [9] | High [9] |

Enthalpy of Adsorption

The enthalpy of adsorption (ΔHad) is a fundamental thermodynamic quantity that directly reflects the strength of the interaction between the adsorbate and the adsorbent.

- Theoretical Basis: Enthalpy of adsorption represents the heat released when an adsorbate molecule attaches to the surface. The magnitude of this enthalpy change directly correlates with the type of forces involved: weak van der Waals interactions for physisorption versus strong chemical bond formation for chemisorption [9].

Experimental Determination: The most common method for determining adsorption enthalpy is through the calculation of the isosteric enthalpy of adsorption. This is typically determined from adsorption isotherms measured at two or more closely spaced temperatures using the van't Hoff relation (Clausius-Clapeyron equation) [10]:

lnP = ΔH/RT − ΔS/Rwhere P is pressure, ΔH is the enthalpy change, ΔS is the entropy change, R is the universal gas constant, and T is the temperature. A plot of lnP against 1/T for a particular uptake gives a straight line with a gradient of ΔH/R [10].

Reversibility

Reversibility refers to the ability to remove adsorbates from the surface under modified conditions, restoring the original adsorbent.

- Physisorption: The weak van der Waals forces allow for easy reversal, often simply by reducing pressure or mildly increasing temperature. This makes physisorption suitable for applications like gas storage and pressure swing adsorption [9].

- Chemisorption: The formation of chemical bonds renders the process largely irreversible under the same conditions. Removing chemisorbed species typically requires significant energy input, such as high temperatures or reactive environments, which can potentially alter the adsorbent surface [9].

Specificity

Specificity describes the selective nature of the interaction between the adsorbate and particular sites on the adsorbent surface.

- Physisorption: This process is non-specific because van der Waals forces are universal and operate on any surface. The amount adsorbed primarily depends on the surface area and porosity of the adsorbent rather than its chemical nature [9].

- Chemisorption: This exhibits high specificity as it requires chemical bonding that is specific to certain surface sites and adsorbates. For example, hydrogen may chemisorb on a ferrous catalyst but not on other materials, and even on a single catalyst, different crystalline faces may exhibit varying chemisorption capacities [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Determining Isosteric Enthalpy of Adsorption

This protocol outlines the procedure for determining the isosteric enthalpy of adsorption using volumetric methods.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Adsorption Experiments

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Adsorbate Gases | Provide the molecular species for adsorption studies | Use research grade (e.g., 99.999% purity) to avoid contamination of surface sites. |

| Reference Cell | Precisely measures known gas volumes | Maintain at constant temperature to ensure volume accuracy. |

| High-Vacuum System | Achieves and maintains ultralow pressure | Essential for degassing and preparing clean surfaces prior to analysis. |

| Temperature-Controlled Bath | Maintains constant isothermal conditions | Liquid N₂ (77 K) and Ar (87 K) are commonly used for temperature control [10]. |

| Pressure Transducers | Accurately measure pressure changes | Calibrate for the specific pressure range of the experiment. |

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Degas the adsorbent sample under high vacuum at elevated temperature (specific to material) for several hours to remove all pre-adsorbed species.

- Isotherm Measurement: Introduce precise doses of the adsorbate gas into the system containing the sample. For each dose, allow the system to reach equilibrium and record the equilibrium pressure.

- Perform this measurement to construct a complete adsorption isotherm (uptake vs. pressure) at a constant temperature, T₁ [10].

- Repeat at Different Temperatures: Repeat Step 2 at two or more different, closely spaced temperatures (T₂, T₃...), ensuring all other conditions remain constant [10].

- Data Analysis:

- For a fixed amount of gas adsorbed (uptake, n), determine the equilibrium pressures (P₁, P₂, P₃...) from the different isotherms.

- For each uptake value, plot lnP against 1/T.

- The isosteric enthalpy of adsorption (ΔH) is calculated from the slope of this plot (slope = ΔH/R) [10].

Differentiating Physisorption and Chemisorption via TPD

Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD) is a powerful technique to assess reversibility and binding strength.

Procedure:

- Adsorption Phase: Expose the clean adsorbent surface to the adsorbate gas at a specific temperature and pressure until saturation is reached.

- Purging: Remove the gas phase and flush the system with an inert gas (e.g., He, Ar) to remove any physisorbed species.

- Desorption Phase: Linearly increase the temperature of the sample at a constant rate (e.g., 10-30 K/min) while monitoring the desorbing species with a mass spectrometer.

- Data Interpretation:

- Low-Temperature Peaks (typically below 100-150 K): Correspond to the desorption of physisorbed molecules, indicating reversible adsorption with low enthalpy.

- High-Temperature Peaks (typically above 300 K): Correspond to the desorption of chemisorbed molecules, indicating strong, often irreversible binding with high enthalpy. The temperature of the peak maximum is directly related to the strength of the adsorption bond.

Advanced Considerations and Theoretical Framework

Multiscale Modeling of Adsorption

Under industrially relevant conditions (high temperature and pressure), the local densities of gas molecules near the catalyst surface can be hundreds of times their bulk values. A multiscale modeling approach that integrates Kohn-Sham density functional theory (KS-DFT) for predicting surface bonding energy with classical DFT (cDFT) to evaluate gas distribution provides a more comprehensive framework [11]. This method accounts for both bond formation (chemisorption) and non-bonded interactions (physisorption) of gas molecules with the catalyst surface, revealing that surface composition is determined by the accessibility of surface sites and their interactions with the surrounding gas phase [11]. The adsorption grand potential (Ωad) in this framework is given by:

Ωad = Gad + ΩcDFT-ad

where Gad is the adsorption free energy from KS-DFT, and ΩcDFT-ad is the penalty grand potential from cDFT, representing the free energy change due to the displacement of gas-phase species during chemisorption [11].

The Role of Rigidity in Thermodynamics

Recent research highlights that classical thermodynamics has historically omitted the role of rigidity, which is a key property distinguishing solids from fluids. The elastic behavior of a solid represents a significant energy reservoir. A theoretical framework links the energy density of sublimation (ρΔHsub/M) to Young's elastic modulus (ϒ), demonstrating that the elastic energy reservoir of solids is large and foundational to understanding their energetics [12]. This perspective is crucial when considering processes like sublimation where rigidity is fully lost.

Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for characterizing an unknown adsorption mechanism based on the key differentiating factors.

Diagram 1: Adsorption Characterization Workflow

Application in Research and Development

The strategic selection of adsorption processes is critical across numerous scientific and industrial domains. In catalyst development, chemisorption is used to quantify active metal surface area, metal dispersion, and the number of active sites, which are critical parameters for optimizing catalytic performance [13]. In drug development, understanding physisorption is vital for designing drug delivery systems where controlled release is desired, while chemisorption principles guide the development of targeted therapies where specific molecular binding is required. For gas storage and separation applications (e.g., H₂, CH₄, CO₂), materials with high surface areas that operate via reversible physisorption are typically preferred due to their lower energy requirements for adsorbent regeneration [10]. The continued refinement of measurement protocols and theoretical models, including multiscale modeling approaches, ensures that researchers can accurately characterize and tailor adsorption properties for advanced applications [11].

In surface science, the interaction between gas or liquid molecules and a solid surface is governed by adsorption processes. The fundamental distinction lies between physisorption (physical adsorption) and chemisorption (chemical adsorption), which differ in the nature of the bonding forces, the number of layers formed, and their overall energetics [14]. Physisorption involves weak van der Waals forces, is reversible, and can lead to multilayer formation. In contrast, chemisorption involves the formation of strong chemical bonds, is often irreversible, and is limited to a monolayer because the chemical bonds saturate the surface active sites [15] [4]. Accurately distinguishing between these mechanisms is critical for researchers and drug development professionals in designing and optimizing processes in catalysis, environmental remediation, and pharmaceutical product development [16] [17]. This application note details the core principles, experimental protocols, and data interpretation methods for characterizing these distinct adsorption behaviors.

Theoretical Background and Key Differences

The primary distinction between these processes lies in the type of adsorbent-adsorbate interaction. Physisorption is characterized by weak, non-specific van der Waals forces, with low adsorption enthalpies typically in the range of 5–50 kJ/mol [14]. As these forces are operative even after the first layer is formed, physisorption can proceed to form multiple layers on the surface. Conversely, chemisorption involves the formation of strong, covalent or ionic chemical bonds, with higher enthalpy changes, often exceeding 50-100 kJ/mol [15]. This process is highly specific to the chemical nature of the adsorbent and adsorbate, occurring only on specific "active sites" and ceasing once a single layer of molecules has formed a chemical bond with these sites [4].

The following table summarizes the characteristic differences between the two processes.

Table 1: Characteristic Differences Between Physisorption and Chemisorption

| Feature | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Force | Weak van der Waals forces [14] | Strong chemical bonds (covalent/ionic) [15] |

| Enthalpy (ΔH) | Low (5–50 kJ/mol) | High (50–100+ kJ/mol) [15] |

| Reversibility | Reversible [14] | Often irreversible [15] |

| Layer Formation | Multilayer possible [18] | Monolayer only [4] |

| Specificity | Non-specific | Highly specific to surface sites [4] |

| Temperature Dependence | Occurs at lower temperatures | Often requires higher temperatures [15] |

| IUPAC Isotherm Types | II, III, IV, V, VI [18] | I (Langmuir-type) [18] |

Visualizing the Adsorption Mechanisms

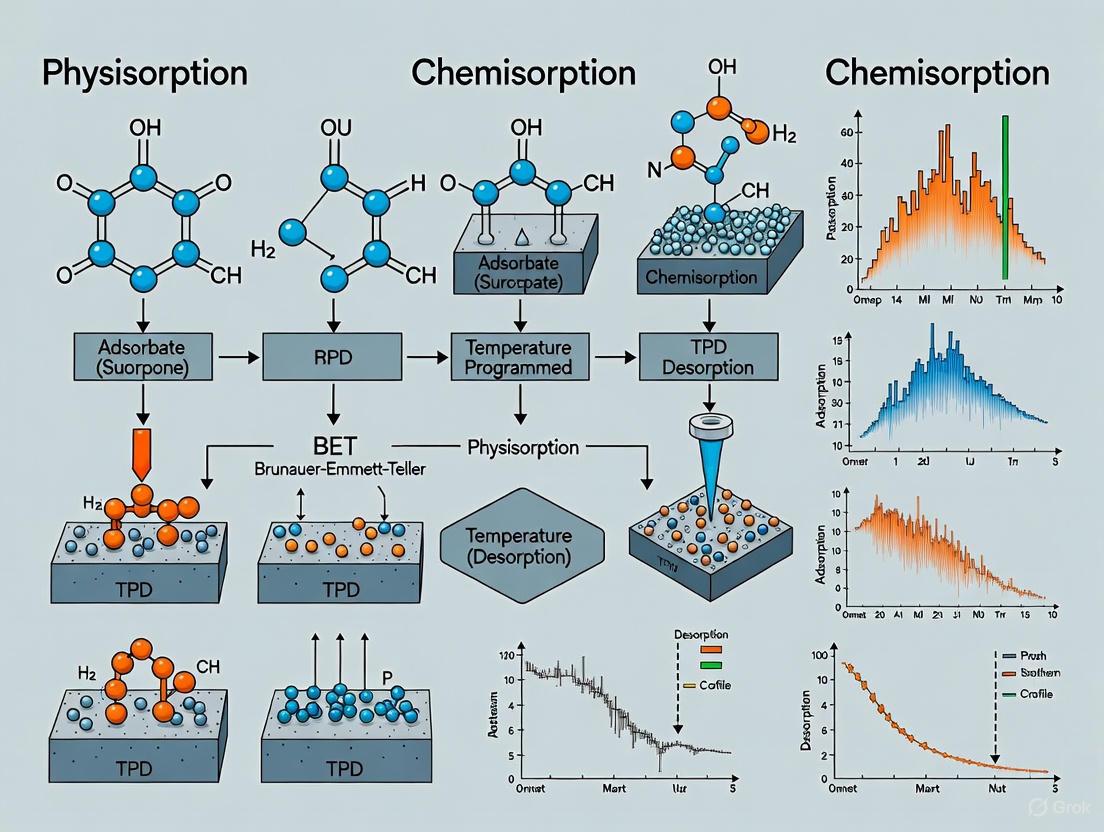

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in layer formation and the nature of interactions at the surface in each process.

Diagram 1: A comparison of multilayer physisorption, where weak van der Waals forces allow for multiple layers to form, and monolayer chemisorption, where strong chemical bonds form exclusively at specific active sites on the surface.

Experimental Protocols for Adsorption Measurement

Distinguishing between physisorption and chemisorption requires a combination of techniques that probe the quantity adsorbed, the strength of adsorption, and the energetic changes involved.

Protocol for Gas Sorption Analysis

This protocol outlines the general steps for characterizing porous materials using gas sorption analyzers, such as the Micromeritics 3Flex or ASAP 2020 Plus [14] [15].

Objective: To determine the surface area, pore size distribution, and chemisorption properties of a solid sample.

Materials:

- Gas Sorption Analyzer: Equipped with high-vacuum system, pressure transducers, and a cryostat (typically liquid N₂ at 77 K) [14].

- Sample Tubes: With sealed ends for outgassing and analysis.

- High-Purity Gases: N₂, Ar, or Kr for physisorption; CO, H₂, O₂, or NH₃ for chemisorption [4].

- Sample: 50–500 mg of dry, powdered material [4].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation (Outgassing):

- Weigh an appropriate amount of sample into a clean, dry sample tube.

- Attach the tube to the analyzer's preparation port.

- Apply vacuum and heat to the sample according to material-specific protocols (e.g., 150–300 °C for several hours) to remove moisture and contaminants from the surface [19].

Physisorption Isotherm Measurement:

- Transfer the degassed sample tube to the analysis port.

- Immerse the sample tube in a cryogenic bath (e.g., liquid N₂ at 77 K).

- Introduce doses of an inert gas (e.g., N₂) and measure the equilibrium pressure at each dose.

- Continue from low pressure (~0.00001 torr) up to saturation pressure (~760 torr) to obtain the full adsorption branch.

- Measure the desorption branch by progressively lowering the pressure [14].

Chemisorption Measurement (Static Volumetric Method):

- After physisorption analysis, evacuate the system to remove the physisorbed gas.

- Set the analysis station to a controlled, elevated temperature relevant to the chemisorption process.

- Introduce small, controlled doses of a reactive probe gas (e.g., CO, H₂).

- After each dose, allow the system to reach equilibrium and record the pressure.

- The amount of gas that remains strongly adsorbed (chemisorbed) at the set temperature is used for calculations [15] [4].

Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD):

- Saturate the sample surface with the probe gas at the analysis temperature.

- Evacuate the system to remove any physisorbed molecules.

- Program the furnace to heat the sample at a constant rate (e.g., 10 °C/min) under a flow of inert gas.

- Use a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) to monitor the desorption of the probe gas as a function of temperature.

- The temperature and area of desorption peaks provide information on the strength and density of active sites [15] [4].

Data Analysis and Calculations

For Physisorption (Surface Area & Porosity):

- BET Surface Area: Use the linearized BET equation with N₂ adsorption data in the relative pressure (P/P₀) range of 0.05–0.30 to calculate the monolayer capacity and specific surface area [14] [18].

- Pore Size Distribution: Apply mathematical models such as Density Functional Theory (DFT) or the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method to the adsorption or desorption isotherm to calculate pore size distribution [14].

For Chemisorption (Active Sites & Dispersion):

- Active Metal Surface Area: From the volume of chemisorbed gas (e.g., H₂ or CO) and assuming a stoichiometry (e.g., one H atom per surface metal atom), calculate the metal dispersion and active surface area [4].

- Active Site Strength: The peak temperature in a TPD profile indicates the strength of binding; higher temperatures correspond to stronger bonds [15].

Application Case Studies

Case Study 1: Pharmaceutical Pollutant Removal via Multilayer Physisorption

A hybrid adsorbent (AC/KCC-1/DEX) was developed for removing Acetaminophen (ACE) and Amoxicillin (AMOX) from water [16].

Findings:

- The adsorption kinetics were best described by the Elovich model, indicative of a heterogeneous surface.

- Advanced statistical physics modelling confirmed a multilayer physisorption mechanism, with additional contributions from chemisorption.

- The material exhibited high adsorption capacities of 87.97 mg/g for ACE and 77.31 mg/g for AMOX [16].

Table 2: Quantitative Adsorption Data for Pharmaceutical Removal [16]

| Parameter | Acetaminophen (ACE) | Amoxicillin (AMOX) |

|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Capacity | 87.97 mg/g | 77.31 mg/g |

| Percentage Removal | 94% | 81% |

| Best-Fit Kinetic Model | Elovich | Elovich |

| Identified Mechanism | Multilayer Physisorption | Multilayer Physisorption |

| Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) | Negative (Spontaneous) | Negative (Spontaneous) |

Case Study 2: Dye Adsorption via Monolayer Chemisorption

Phyto-synthesized CuO nanoparticles were used for the adsorption of Congo red (CR) dye [17]. In a separate study, a CA@Lap hydrogel adsorbed Crystal Violet (CV) and Methylene Blue (MB) via monolayer chemisorption [20].

Findings for CuO Nanoparticles:

- Kinetic studies showed the adsorption followed a pseudo-second-order model (R² = 0.9997), which is characteristic of chemisorption.

- The maximum adsorption capacity for CR was 6.99 mg/g.

- Thermodynamic parameters (ΔH° = –34.35 kJ mol⁻¹) supported a combination of physical and chemical adsorption mechanisms [17].

Findings for CA@Lap Hydrogel:

- The adsorption mechanisms for CV and MB were identified as monolayer chemisorption [20].

- The hydrogel achieved ultra-high adsorption capacities of 2245.7 mg/g for CV and 3840.8 mg/g for MB [20].

Case Study 3: Synergistic Physico-Chemisorption for Gas Capture

A computational study screened nitrogen-rich Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) for capturing radioactive methyl iodide (CH₃I) [21].

Findings:

- The mechanism involves an initial chemisorption step where CH₃I undergoes N-methylation with specific N-sites in the COF, forming a stable chemical bond.

- This chemisorbed layer then acts as a substrate for further physisorption of additional CH₃I molecules through van der Waals interactions.

- The top-performing COFs (NH₂-Th-Bta COF and PTP-COF) achieved record-high gravimetric uptakes of 0.687 g g⁻¹ and 0.557 g g⁻¹, respectively, at trace concentrations (50 ppm), demonstrating the power of a synergistic mechanism [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and their functions in adsorption studies, as derived from the cited research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Adsorption Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Fibrous Silica (KCC-1) | A support material with unique dendritic, fibre-like morphology, large pore volume, and highly accessible surface area [16]. | Hosting and dispersing adsorptive sites in hybrid adsorbents [16]. |

| Maltodextrin (DEX) | A biodegradable, hydroxyl-rich polysaccharide used as a functionalization agent to introduce hydrogen bonding and polar interactions [16]. | Improving hydrophilicity and adsorption selectivity for polar pharmaceutical molecules [16]. |

| Probe Gases (H₂, CO, O₂, NH₃) | Reactive gases used in chemisorption experiments to titrate specific types of active sites on a catalyst surface [4]. | Determining metal dispersion, active surface area, and acid/base site strength [15] [4]. |

| Congo Red (CR) | A synthetic azo dye used as a model adsorbate for testing adsorption performance in aqueous solutions [17]. | Evaluating the efficiency and capacity of novel adsorbents like CuO nanoparticles [17]. |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) | Crystalline porous polymers with modular design and high stability, allowing for precise functionalization [21]. | Designed with specific N-sites for synergistic chemisorption and physisorption of gases like CH₃I [21]. |

| Malva sylvestris Extract | A plant extract containing bioactive chemicals (e.g., flavonoids, polyphenols) that act as reducing and stabilizing agents [17]. | Green synthesis of metal oxide nanoparticles (e.g., CuO) for environmentally friendly adsorbents [17]. |

Workflow for Mechanism Identification

A systematic approach combining multiple characterization techniques is required to conclusively identify an adsorption mechanism. The following diagram outlines a decision-making workflow.

Diagram 2: A workflow for identifying adsorption mechanisms by analyzing isotherm type, kinetic models, thermodynamic parameters, and temperature-programmed desorption data.

Temperature and Pressure Dependence in Adsorption Phenomena

Adsorption, the process by which atoms or molecules accumulate on a solid surface, is a fundamental phenomenon critical to numerous scientific and industrial applications. The efficiency and mechanism of this process are predominantly governed by two extrinsic parameters: temperature and pressure [22]. Understanding their interdependence is essential for designing adsorption systems, from gas storage and separation to catalytic reactions and drug delivery.

This application note provides a structured overview of the temperature and pressure dependence in both physisorption and chemisorption. It includes key theoretical models, summarized quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols for gravimetric analysis, and a catalog of essential research reagents. The content is framed within a broader thesis on sorption measurement methods, serving as a practical guide for researchers and scientists.

Theoretical Framework: Adsorption Isotherms

An adsorption isotherm is a curve representing the equilibrium relationship between the concentration of adsorbate on the adsorbent surface and its concentration in the bulk phase at a constant temperature [23]. They provide macroscopic insights into adsorption capacity, strength, and the nature of the surface [23].

Several models describe this relationship, each with specific assumptions about the adsorption process. The table below summarizes the most prevalent models used to interpret experimental data.

Table 1: Key Adsorption Isotherm Models and Their Characteristics

| Isotherm Model | Linear Equation Form | Fundamental Assumptions | Key Parameters & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir [23] [24] | C<sub>e</sub>/q<sub>e</sub> = 1/(K<sub>L</sub>q<sub>m</sub>) + C<sub>e</sub>/q<sub>m</sub> |

• Homogeneous surface• Monolayer coverage• Identical sites, no adsorbate interaction | • q<sub>m</sub> (mg/g): Maximum monolayer capacity• K<sub>L</sub> (L/mg): Langmuir constant related to affinity• R<sub>L</sub>: Separation factor indicating favorability |

| Freundlich [23] | ln q<sub>e</sub> = ln K<sub>F</sub> + (1/n) ln C<sub>e</sub> |

• Heterogeneous surface• Multilayer adsorption | • K<sub>F</sub>: Freundlich constant (capacity indicator)• 1/n: Heterogeneity factor (favorability indicator) |

| Temkin [23] | q<sub>e</sub> = (RT/b<sub>t</sub>) ln K<sub>T</sub> + (RT/b<sub>t</sub>) ln C<sub>e</sub> |

• Heat of adsorption decreases linearly with coverage• Uniform binding energy distribution | • K<sub>T</sub> (L/g): Equilibrium binding constant• b<sub>t</sub>: Temkin constant related to heat of adsorption |

| Dubinin–Radushkevich (D-R) [23] | ln q<sub>e</sub> = ln q<sub>m</sub> - βε²ε = RT ln(1 + 1/C<sub>e</sub>) |

• Applies to homogeneous and heterogeneous surfaces• Based on pore-filling mechanism | • β: Activity coefficient• E (kJ/mol): Mean sorption energy, distinguishing physical (E < 8 kJ/mol) vs. chemical (8 < E < 16 kJ/mol) adsorption |

Temperature and Pressure Dependence in Practice

The interplay between temperature (T) and pressure (P) directly dictates adsorption capacity. The general trends and underlying mechanisms are visualized below.

Diagram 1: T and P Effect on Adsorption Capacity

For physisorption, which relies on weak van der Waals forces, adsorption is exothermic. Consequently, capacity decreases as temperature increases, as the adsorbate molecules possess greater thermal energy to overcome the surface potential well. Higher pressure increases the driving force for mass transfer to the surface, enhancing capacity [22] [25].

In chemisorption, which involves the formation of stronger chemical bonds, the relationship is more complex. While still exothermic, the higher energy barrier means it often requires a specific activation energy and may occur within a narrower temperature window. The dependence on pressure follows a similar trend to physisorption but is also influenced by the surface coverage of chemically active sites [25].

Experimental data consistently validates these principles. For instance, a study on methane adsorption in transitional facies shale found that adsorption capacity increased with pressure but decreased with rising temperature across a range of 40–70 °C [24]. Furthermore, a linear relationship was observed between the Langmuir volume (VL, indicating capacity) and Langmuir pressure (PL, related to affinity) as temperature changed [24].

Experimental Protocol: Gravimetric Method

The following detailed protocol for conducting high-pressure isothermal adsorption experiments is adapted from studies on shale gas [24] and gas adsorption in Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [26], using a magnetic suspension balance (MSB) system.

Materials and Equipment

- Adsorbent: e.g., synthesized Cu-BTC particles [26] or crushed shale samples (40-60 mesh) [24].

- Adsorbate Gas: High-purity methane, CO₂, N₂, or H₂, depending on the study.

- Instrumentation: Rubotherm magnetic suspension balance (MSB) or equivalent gravimetric system.

- Auxiliary Systems: High-pressure chamber, vacuum system, ISCO pump for gas injection, precision temperature control system, data acquisition computer [24].

Step-by-Step Procedure

Diagram 2: Gravimetric Adsorption Experiment Workflow

Key Calculations:

- Buoyancy Correction: The true mass of adsorbed gas is derived from the balance reading, corrected for the buoyant force exerted by the fluid on the sample and sample holder [24]: ( m{\text{ads}} = m{\text{measured}} + \rho{\text{gas}} \cdot V{\text{sample+holder}} )

- Adsorption Capacity: The amount adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent is calculated as ( q = m{\text{ads}} / m{\text{sample}} ).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Adsorption Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cu-BTC (Basolite C300) | A metal-organic framework (MOF) with high surface area and tunable porosity, used as a benchmark adsorbent. | Equilibrium and kinetic studies of CO₂, CH₄, and N₂ adsorption [26]. |

| Transitional Facies Shale | A complex, heterogeneous natural adsorbent with high organic carbon content, used for studying gas occurrence in reservoirs. | High-pressure methane adsorption/desorption experiments [24]. |

| Amine-Functionalized MOFs | MOFs post-synthetically modified with amine groups to introduce strong, specific chemisorption sites for acidic gases like CO₂. | Selective CO₂ capture from flue gas or direct air capture, even under humid conditions [25] [27]. |

| Ni-decorated C12N12 Nanoclusters | A synthetic carbon-based nanomaterial where transition metals act as primary sites for H₂ adsorption via electrostatic and orbital interactions. | Hydrogen storage research; can bind up to eight H₂ molecules with favorable energetics for reversibility [28]. |

| Helium (Ultra-high Purity) | An inert, non-adsorbing gas used for dead volume calibration and buoyancy correction in volumetric and gravimetric systems. | Determination of the sample volume during the buoyancy test prior to adsorption measurement [24]. |

| Magnetic Suspension Balance (MSB) | A key instrument for gravimetric analysis that physically separates the microbalance from the high-pressure environment, ensuring accuracy. | High-pressure isothermal adsorption measurements up to 30 MPa [24]. |

The Role of Surface Area, Porosity, and Surface Chemistry

In the fields of material science and drug development, the interfacial properties of solids—specifically surface area, porosity, and surface chemistry—are critical parameters that dictate material performance and functionality. These properties directly influence a wide range of behaviors including catalytic activity, adsorption capacity, drug dissolution rates, and stability. Within the broader context of physisorption and chemisorption measurement methods research, accurate characterization of these properties provides fundamental insights into material behavior across diverse applications. Surface area determines the available space for molecular interactions, porosity defines the architecture and accessibility of this space, while surface chemistry governs the nature and strength of these interactions. This application note details standardized protocols and analytical methodologies for the comprehensive characterization of these essential material properties, with particular emphasis on techniques relevant to pharmaceutical development and advanced material design.

Surface Area Analysis

Theoretical Foundations

The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) theory is the most widely applied method for determining the specific surface area of porous and non-porous materials. The theory extends the Langmuir model to account for multilayer adsorption and is based on several key assumptions: gas molecules physically adsorb on a solid in layers infinitely, the Langmuir model applies to each layer, and the heat of adsorption for the first layer is unique while subsequent layers equal the heat of liquefaction [29].

The linearized BET equation takes the form: [ \frac{P/Po}{W(1-P/Po)} = \frac{1}{WmC} + \frac{C-1}{WmC}(P/Po) ] where (P/Po) is the relative pressure, (W) is the mass of adsorbed gas, (Wm) is the monolayer capacity, and (C) is the BET constant related to the adsorption energy [29]. For materials with polar surfaces, such as pharmaceuticals and food products, the Guggenheim-Anderson-de Boer (GAB) equation extends the applicability of the BET model to higher relative pressures (up to 0.8 (P/Po)) by introducing a constant (k) that corrects for the modified properties of molecules in layers beyond the first monolayer [29].

Experimental Protocol: BET Surface Area Measurement

Principle: The method determines the specific surface area by measuring the quantity of inert gas (typically nitrogen at 77 K) adsorbed as a monolayer on a solid surface, following the BET theory [30] [31].

Equipment and Reagents:

Sample Preparation (Degassing):

- Weigh an appropriate amount of sample into a clean, dry sample tube.

- Secure the tube to the degas port of the analyzer.

- Apply heat and vacuum to remove physisorbed contaminants (e.g., water vapor, hydrocarbons). Typical conditions are 423 K (150 °C) for 10 hours under vacuum, though parameters must be optimized based on material thermal stability [30] [33]. For temperature-sensitive pharmaceuticals, lower temperatures and extended times may be used.

Analysis Procedure:

- Transfer the degassed sample tube to the analysis port.

- Immerse the sample tube in a liquid nitrogen bath (77 K) to maintain isothermal conditions.

- The analyzer introduces incremental doses of nitrogen gas into the sample cell.

- The system measures the volume of gas adsorbed at each equilibrium pressure, typically across a relative pressure ((P/P_o)) range of 0.05 to 0.35 [33].

- The software constructs an adsorption isotherm (volume adsorbed vs. relative pressure).

Data Analysis:

- The software applies the BET equation to the linear region of the isotherm (usually (P/P_o = 0.05-0.35)).

- The monolayer capacity ((W_m)) is derived from the slope and intercept of the BET plot.

- The specific surface area ((S{BET})) is calculated using the equation: [ S{BET} = \frac{W_m \cdot N \cdot \sigma}{M} ] where (N) is Avogadro's number, (\sigma) is the cross-sectional area of the adsorbate molecule (0.162 nm² for N₂), and (M) is the molecular weight of the adsorbate.

Quality Control:

- Use certified surface area reference materials for instrument calibration.

- Ensure the correlation coefficient (R²) of the BET plot is >0.9999.

- The C constant should be positive for valid analysis.

The experimental workflow for BET surface area analysis is summarized in the diagram below.

Advanced Considerations

For microporous materials (pores < 2 nm), standard BET analysis may overestimate surface area. The BET Assistant AI tool can help identify the appropriate linear region for more accurate results [33]. For ultramicroporous characterization, probe gases like carbon dioxide at 273 K are recommended due to their higher diffusivity at higher temperatures, allowing them to access pores smaller than 0.5 nm [32] [33].

Table 1: Standard Gases for Surface Area and Porosity Analysis

| Gas | Analysis Temperature | Primary Application | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| N₂ | 77 K | BET Surface Area, Meso/Micropores | Standard method, high accuracy, well-established protocols |

| Kr | 77 K | Very Low Surface Area (< 1 m²/g) | Higher sensitivity due to lower vapor pressure |

| CO₂ | 273 K (Ice Bath) | Ultramicropores (< 0.7 nm) | Faster diffusion into smallest pores at higher temperature |

| Ar | 77 K | Micropore Analysis | Avoids quadrupole moment issues with N₂ on certain surfaces |

Porosity Characterization

Pore Classification and Measurement Techniques

Porosity refers to the void spaces within a material, which are classified by IUPAC based on their width: micropores (< 2 nm), mesopores (2–50 nm), and macropores (> 50 nm) [31] [34]. The pore size distribution (PSD), pore volume, and pore connectivity are critical for understanding molecular transport, accessibility of active sites, and loading capacity.

Gas Physisorption is the primary technique for characterizing micro- and mesopores. It involves analyzing the physical adsorption and desorption of an inert gas to generate an isotherm, which is then interpreted using various models to extract pore structural information [35] [31]. Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry is used complementary for macroporous materials, relying on the non-wetting behavior of mercury forced into pores under high pressure [35] [34].

Experimental Protocol: Pore Size Distribution by Gas Physisorption

Principle: The method determines pore size distribution by analyzing the capillary condensation of gas (typically N₂ at 77 K) within the pores of a material. The pressure at which condensation occurs is directly related to the pore diameter via the Kelvin equation [31].

Equipment and Reagents:

- Gas adsorption analyzer (e.g., Quantachrome NOVA-e, Micromeritics 3Flex)

- High-purity nitrogen gas

- Liquid nitrogen Dewar

- Pre-degassed sample (see Section 2.2)

Analysis Procedure:

- After degassing, the sample is cooled to 77 K using liquid nitrogen.

- The relative pressure ((P/P_o)) is gradually increased from near-zero (e.g., 10⁻⁵) to 0.995, and the quantity of gas adsorbed is measured at each equilibrium point to generate the adsorption branch.

- The pressure is then progressively decreased to measure the desorption branch, creating a full adsorption-desorption isotherm [31].

- For high-resolution analysis, 40 or more data points are collected [33].

Data Analysis and Pore Size Models:

- Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) Method: The most common method for mesopore size distribution. It applies the Kelvin equation to the desorption isotherm (or adsorption isotherm) to calculate pore volumes and diameters, assuming cylindrical pore geometry [31].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Non-Local DFT (NLDFT): These advanced models provide more accurate PSDs, especially for microporous materials, by considering the molecular-level structure of the adsorbed fluid. Quenched Solid DFT (QSDFT) is a further refinement for heterogeneous surfaces like carbons [31] [33].

- NLDFT Dual Isotherm Deconvolution: This method combines isotherms from two different probe gases (e.g., N₂ and CO₂) to generate a continuous PSD from ultramicropores into the mesopore range, providing the most complete picture for complex porous networks like activated carbons [32] [33].

Table 2: Models for Pore Size Distribution Analysis from Gas Physisorption

| Model | Applicable Pore Range | Principle | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| BJH | Mesopores (2–50 nm) | Kelvin equation for capillary condensation | Quality control, comparative studies of mesoporous materials |

| NLDFT | Micro- and Mesopores (0.5–50 nm) | Molecular statistical approach assuming idealized pore geometry | Zeolites, ordered silicas, MCM-type materials |

| QSDFT | Micro- and Mesopores (0.5–50 nm) | Accounts for surface roughness and heterogeneity | Activated carbons, disordered porous polymers, biochars |

Advanced Porosity Analysis

The 3Flex analyzer allows for sequential and combined analysis using multiple techniques (physisorption, chemisorption, vapor sorption) on a single sample without removal, providing a comprehensive material characterization profile [32]. For a complete pore analysis from micro- to macropores, data from gas physisorption can be combined with mercury intrusion porosimetry results in the software to create a seamless PSD over several orders of magnitude [32].

Surface Chemistry and Chemisorption

The Role of Surface Chemistry

While surface area and porosity define the physical landscape, surface chemistry determines the nature and energy of interactions between the solid and surrounding molecules. Specific chemical functional groups, acid/base sites, and metal centers govern processes like catalyst activity and selectivity, binding of APIs to excipients, and non-specific adsorption in analytical systems [36] [32].

Mitigating Non-Specific Adsorption: An Application Note

Challenge: Oligonucleotides, critical in genetic research and therapeutics, are prone to non-specific adsorption onto metal surfaces (e.g., stainless-steel HPLC systems and columns) due to interactions with their electron-rich phosphodiester backbone. This leads to poor recovery, peak tailing, and irreproducible results [36].

Solution:

- Traditional Passivation: A time-consuming process of masking active metal sites by repeatedly injecting a high concentration of the analyte or a passivating agent. This is not a longstanding solution [36].

- MaxPeak High Performance Surfaces (HPS) Technology: Employs hardware and columns with a proprietary surface chemistry that minimizes interaction with metal-sensitive analytes. This provides "out-of-the-box" performance without passivation, significantly improving recovery and reproducibility for oligonucleotides in HILIC analysis [36].

Experimental Data: A study compared the performance of traditional stainless-steel systems versus systems with MaxPeak HPS Technology for analyzing a MassPREP OST Standard oligonucleotide.

- Stainless-System + Steel Column: Initial recovery was low (~0%) and increased only after 20 passivation injections, demonstrating significant adsorption [36].

- HPS System + HPS Column: Achieved an average recovery of 98% from the initial injections, with excellent peak shape and reproducibility, effectively eliminating non-specific adsorption [36].

Experimental Protocol: Static Chemisorption for Active Metal Surface Area

Principle: Chemisorption involves the formation of chemical bonds between a probe gas and specific active sites on a surface. Static volumetric chemisorption measures the quantity of gas chemisorbed to determine active metal surface area, dispersion, and particle size in catalysts [32].

Equipment:

- Chemisorption analyzer (e.g., Micromeritics 3Flex with chemisorption option)

- High-purity probe gases (e.g., H₂, CO, O₂) and inert carrier gas (He, Ar)

- High-temperature furnace.

Sample Preparation (In-situ Reduction):

- The sample is placed in a quartz cell and heated under vacuum or inert gas flow.

- A reducing gas (e.g., 5% H₂ in Ar) is introduced while the temperature is ramped (e.g., to 400 °C) to reduce surface metal oxides to their active metallic state.

- The sample is then evacuated to remove any physisorbed species.

Analysis Procedure (Titration Method):

- The sample is exposed to repeated small, pulsed doses of the probe gas (e.g., H₂ for metals) at the analysis temperature (e.g., 35 °C).

- Each dose is allowed to equilibrate, and the pressure change is monitored.

- The process continues until no further adsorption is detected, indicating saturation of the active sites.

- The system is then evacuated to measure the amount of strongly chemisorbed gas.

Data Analysis:

- The total volume of chemisorbed gas is used to calculate the number of surface metal atoms.

- The active metal surface area is calculated assuming a stoichiometry (e.g., 1 H atom per surface metal atom) and a cross-sectional area for the metal atom.

- Metal dispersion (% of metal atoms on the surface) and average crystallite size are calculated from these values.

The logical relationship between measurement techniques and the material properties they characterize is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity N₂ Gas (≥99.99%) | Primary adsorbate for BET surface area and meso/micropore analysis. | Essential for generating accurate, contaminant-free isotherms. Low purity can lead to skewed results. |

| Liquid N₂ | Cryogenic bath (77 K) for maintaining isothermal conditions during N₂ adsorption. | Level must be kept constant during analysis for stable temperature and pressure readings. |

| High-Purity CO₂ Gas | Adsorbate for characterizing ultramicropores (< 1.5 nm). | Used at 273 K (ice-water bath) for faster diffusion kinetics into the smallest pores [33]. |

| Micromeritics 3Flex Analyzer | High-performance instrument for physisorption, chemisorption, and vapor sorption. | Features a 0.1 torr transducer for ultramicropore analysis and three independent analysis ports [32]. |

| Degassing Station | Sample preparation for removal of physisorbed contaminants (e.g., H₂O). | Parameters (temperature, time) must be optimized to prevent altering or degrading the sample [30]. |

| MaxPeak HPS Columns/Systems | LC hardware with modified surface chemistry to mitigate non-specific adsorption. | Critical for accurate bioanalysis of metal-sensitive molecules like oligonucleotides and phosphorylated proteins [36]. |

| Quantachrome NOVA-e Series | Gas adsorption analyzer for surface area and porosity. | Designed to comply with standardized protocols like the European Biochar Certificate [33]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Calibration and validation of surface area and pore size measurements. | Necessary for quality control and ensuring data integrity across different instruments and labs. |

The rigorous characterization of surface area, porosity, and surface chemistry is foundational to advancing research in catalysis, material science, and pharmaceutical development. The application notes and detailed protocols provided herein—from standard BET surface area analysis and advanced NLDFT pore size modeling to specialized chemisorption and surface passivation techniques—offer a framework for obtaining reliable and meaningful data. As evidenced by the integration of machine learning for material screening [37] and the development of advanced surface technologies to solve analytical challenges [36], this field continues to evolve. Employing these standardized methods allows researchers to deepen their understanding of structure-property relationships, ultimately guiding the rational design of more effective materials, catalysts, and therapeutic agents.

Core Measurement Techniques: From BET Analysis to Temperature-Programmed Methods

Physisorption Analysis with BET (Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) for Surface Area and Porosity

Physisorption analysis based on the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) theory provides a fundamental methodology for determining the specific surface area and porosity of solid materials, forming a crucial component of surface characterization techniques in both academic research and industrial applications [38] [39]. First published in 1938 by Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller, this theory extends Langmuir's concept of monolayer adsorption to multilayer adsorption systems, enabling accurate surface area measurements for diverse materials ranging from pharmaceuticals to advanced catalysts [38]. The widespread adoption of BET analysis across scientific disciplines stems from its ability to provide critical information about material properties that directly impact performance characteristics such as dissolution rates, catalytic activity, moisture retention, and shelf life [38].

Within the broader context of physisorption and chemisorption measurement methods research, BET theory specifically addresses physical adsorption (physisorption), where gas molecules adhere to solid surfaces primarily through van der Waals forces without forming chemical bonds [14]. This contrasts with chemisorption, which involves stronger chemical bonds and typically results in irreversible adsorption [14]. The BET method's particular strength lies in its applicability to both porous and non-porous materials regardless of particle size and shape, making it an indispensable tool for researchers characterizing novel materials and optimizing industrial processes [38].

Theoretical Principles of BET Analysis

Fundamental Concepts and Equations

The BET theory is founded on several key hypotheses that extend the Langmuir model for monolayer adsorption to multilayer systems. The fundamental assumptions include: (1) gas molecules physically adsorb on a solid in theoretically infinite layers; (2) gas molecules interact only with adjacent layers; (3) the Langmuir theory can be applied to each layer; (4) the enthalpy of adsorption for the first layer is constant and greater than that for subsequent layers; and (5) the enthalpy of adsorption for the second and higher layers equals the enthalpy of liquefaction [39]. These premises lead to the derivation of the classic BET equation:

[ \frac{p/p0}{v[1-(p/p0)]} = \frac{c-1}{vm c} \left( \frac{p}{p0} \right) + \frac{1}{v_m c} ]

where (p) is the equilibrium pressure, (p0) is the saturation pressure of the adsorbate at the analysis temperature, (v) is the adsorbed gas quantity, (vm) is the monolayer capacity, and (c) is the BET constant related to the adsorption energy [39]. The term (c) is exponentially related to the difference between the heat of adsorption of the first layer ((E1)) and the heat of liquefaction ((EL)) according to:

[ c = \exp\left( \frac{E1 - EL}{RT} \right) ]

where (R) is the gas constant and (T) is the absolute temperature [39].

For most solids using nitrogen as the adsorbate, the linear relationship described by the BET equation is restricted to a relative pressure ((p/p0)) range of 0.05 to 0.35 [38]. Within this region, a plot of (1/[v(p0/p)-1]) versus (p/p0) yields a straight line with slope (s = (c-1)/(vm c)) and intercept (i = 1/(vm c)) [38] [39]. The monolayer capacity (vm) is then calculated from:

[ v_m = \frac{1}{s + i} ]

The specific surface area (S_{BET}) is subsequently determined using:

[ S{BET} = \frac{vm N \sigma}{m} ]

where (N) is Avogadro's number, (\sigma) is the cross-sectional area of the adsorbate molecule, and (m) is the sample mass [38] [39]. For nitrogen adsorption at 77 K, the generally accepted value for (\sigma) is 16.2 Ų/molecule (0.162 nm²) [38].

Comparison of Physisorption and Chemisorption

Understanding BET analysis requires distinguishing between physisorption and chemisorption processes, as both represent important but distinct gas-solid interaction mechanisms with different applications in materials characterization.

Table 1: Comparison between Physisorption and Chemisorption Processes

| Parameter | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Forces | Weak van der Waals forces | Strong chemical bonds |

| Reversibility | Reversible | Often irreversible |

| Temperature Range | Typically occurs at cryogenic temperatures (e.g., 77 K for N₂) | Can occur across a wide temperature range, often up to 1100°C |

| Application in BET | Primary mechanism for surface area and porosity measurements | Used for catalyst characterization, surface modification studies |

| Typical Gases | N₂, Ar, Kr, CO₂ | CO, H₂, NH₃, O₂, SO₂ |

| Enthalpy of Adsorption | Similar to liquefaction enthalpy | Significantly higher, similar to chemical bond energies |

Experimental Protocols for BET Analysis

Sample Preparation and Degassing

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining accurate and reproducible BET surface area measurements. The initial and most crucial step involves sample degassing to remove moisture and other contaminants from the sample surface [41]. This process typically involves subjecting the sample to elevated temperatures and vacuum conditions to eliminate physically bonded surface impurities [41]. For most materials, degassing is performed under vacuum at temperatures high enough to remove contaminants without altering the sample's intrinsic structure [41]. The Autosorb Degasser, for instance, offers pretreatment in vacuum from room temperature up to 350°C across six independent stations [40]. Special consideration must be given to hydrate materials susceptible to phase transformation during degassing, as conventional degassing may induce dehydration and alter the material's properties [42].

Measurement Procedure

Following proper degassing, the BET analysis proceeds through a systematic workflow to obtain the adsorption isotherm:

The specific experimental parameters must be carefully controlled throughout this process. The sample is cooled using a cryogenic liquid, typically liquid nitrogen at 77 K for nitrogen adsorption measurements [38] [41]. The temperature of the solid sample is maintained constant under isothermal conditions while the pressure or concentration of the adsorbing gas is systematically increased [38]. The amount of gas adsorbed at each pressure point is monitored to create the adsorption isotherm, which represents the foundation for all subsequent calculations [41].

Gas Selection and Sample Quantity Considerations

Appropriate selection of adsorbate gas and sample quantity is essential for obtaining accurate BET surface area measurements. The choice depends primarily on the expected surface area of the material.

Table 2: Gas Selection and Sample Requirements for BET Analysis

| Parameter | Nitrogen (N₂) | Krypton (Kr) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Application | Materials with surface area >1 m²/g | Low surface area materials (<1 m²/g) |

| Analysis Temperature | 77 K (liquid nitrogen) | 77 K (liquid nitrogen) |

| Vapor Pressure at 77 K | 760 mmHg | 2.5 mmHg |

| Advantages | Widely used, well-characterized | Greater accuracy for low surface areas due to lower vapor pressure |

| Typical Sample Amount | 500 mg to 1 g (depending on expected surface area) | Smaller amounts may be sufficient |

| Cross-sectional Area | 0.162 nm²/molecule | 0.202 nm²/molecule |

The optimal sample amount depends on the instrument type, sample tube size, and the desired measurement accuracy. Generally, the total surface area of the sample should be at least 7.62 m² to maintain uncertainty below 5% for analysis in a ½" OD sample tube using nitrogen at 77 K [43]. For materials with an expected specific surface area of 10 m²/g, this translates to approximately 0.762 g of sample [43]. Single-point measurements are typically offered for quality control of established materials with known specific surface area, while multi-point analysis is recommended for unknown materials to ensure accuracy [41].

Data Interpretation and Analysis

BET Isotherm Interpretation

The adsorption isotherm obtained from BET measurements provides critical information about the material's surface and pore characteristics. A typical BET isotherm displays the relationship between the relative pressure (P/P₀) and the volume of gas adsorbed. The linear region of the BET plot generally falls within the relative pressure range of 0.05 to 0.35 for most solids using nitrogen as the adsorbate [38]. Beyond surface area determination, the complete isotherm shape yields valuable insights into porosity and adsorption mechanisms, with different isotherm classifications (Type I-VI) indicating distinct material characteristics and pore structures.

Porosity Analysis

Gas adsorption enables comprehensive characterization of a material's porosity, revealing structural insights that complement surface area information. As gas pressure increases, pores within the material fill systematically, beginning with smaller pores and progressing to larger ones until saturation occurs [14]. Gas adsorption is generally applicable to pores ranging from approximately 0.35 nm to 400 nm in diameter [14].

Table 3: Porosity Characterization by Gas Adsorption

| Pore Classification | Size Range | Typical Calculation Models |

|---|---|---|

| Micropore | < 2 nm | Density Functional Theory (DFT), M-P Method, Dubinin Plots (D-R, D-A), Horvath-Kawazoe (H-K), t-plot |

| Mesopore | 2-50 nm | Barrett, Joyner, and Halenda (BJH), Density Functional Theory (DFT), Dollimore-Heal (DH) |

| Macropore | > 50 nm | Barrett, Joyner, and Halenda (BJH), Density Functional Theory (DFT), Dollimore-Heal (DH) |

| Special Cases | > 400 nm | Mercury intrusion porosimetry (3 nm to 1100 µm) |

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from experimental data to comprehensive material characterization:

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful BET analysis requires specific reagents and instrumentation tailored to the material properties and information requirements.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Instruments for BET Analysis

| Reagent/Instrument | Function/Specification | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen Gas (N₂) | Primary adsorbate for standard surface area measurement | High purity (99.99%+), suitable for materials with SSA >1 m²/g, cross-sectional area: 0.162 nm²/molecule |

| Krypton Gas (Kr) | Adsorbate for low surface area materials | Preferred for SSA <1 m²/g, lower vapor pressure enables greater accuracy for small surface areas |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Cryogen for maintaining 77 K analysis temperature | Standard coolant for N₂ and Kr adsorption measurements |

| Degassing Station | Sample preparation under vacuum and elevated temperature | Removes moisture and contaminants; typically 6 stations, up to 350°C |

| Physisorption Analyzer | Measures gas adsorption at controlled pressures and temperatures | Static volumetric method; examples: Autosorb iQ, ASAP series, 3Flex |

| Sample Tubes | Containers for solid samples during analysis | Various sizes (¼" to ½" OD); with/without filler rods depending on application |

Modern physisorption analyzers such as the Autosorb iQ2 offer comprehensive capabilities for both physisorption and chemisorption measurements, with temperature ranges from 77-120 K for physisorption and up to 1100°C for chemisorption studies [40]. The ASAP 2020 Plus provides a high-resolution surface area and porosity analyzer suitable for research, development, and quality control applications, while the TriStar II Plus enables highest-throughput automated BET surface area analysis through three-sample parallel measurements [14].

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Material Sciences

Pharmaceutical Development

BET surface area analysis plays a critical role in pharmaceutical development, where specific surface area significantly impacts product performance. Many pharmaceutical powder blend ingredients, including active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), binders, lubricants, and excipients are characterized by their BET surface area to ensure optimal dissolution rates, cohesion, and bio-availability [38]. The surface area directly influences drug dissolution behavior, as higher surface area typically enhances dissolution rates, potentially improving bioavailability [38]. This is particularly important for poorly soluble drugs where dissolution rate-limited absorption may occur.

Special considerations apply for hydrate-anhydrate systems susceptible to phase transformation during conventional BET analysis. Standard degassing under low pressure may induce dehydration in certain pharmaceutical hydrates, altering their physical structure and compromising measurement accuracy [42]. For such sensitive materials, inverse gas chromatography (IGC) has emerged as a reliable alternative technique, allowing SSA measurement under controlled relative humidity conditions that maintain physical stability [42]. Studies on trehalose dihydrate and thiamine HCl non-stoichiometric hydrate have demonstrated that these materials undergo partial phase transformation to anhydrous forms during conventional BET analysis but remain stable during IGC measurements [42].

Advanced Material Characterization

Beyond pharmaceutical applications, BET analysis supports diverse fields through characterization of material properties that dictate performance:

Catalysis: Heterogeneous catalysts, primarily solids, are used in many industrial chemical processes and typically comprise a reactive species on a non-reactive or inert support [38]. The surface area of both components influences the reaction rate and yield, with higher surface area providing more active sites that generally improve reaction efficiency [38] [44].

Battery Technology: The performance of various battery components, including anodes, cathodes, and separator membranes, is significantly affected by their surface areas [38]. Properties such as charging and discharging rates, impedance, and capacity correlate with the surface areas of these materials [38]. Electrodes with high surface area can enhance charge transfer and energy storage capacity [44].

Carbon Materials and Graphene: BET analysis serves as a quality control tool for characterizing graphene and graphite powders [45]. The theoretical surface area of monolayer graphene is 2630 m²/g, and as layers stack to form non-porous graphitic materials, the specific surface area decreases proportionately with increasing number of layers (S = 2630/N m²/g) [45]. This relationship enables estimation of layer numbers in graphitic materials, though accuracy can be affected by factors such as amorphous carbon content and aggregation upon drying [45].

Ceramics and Construction Materials: Ceramics used in applications ranging from everyday items to advanced technical products like semiconductors and microchips are characterized for surface area to understand impacts on sintering behavior, thermal properties, and moisture retention [38]. Similarly, the fineness of cement and concrete directly influences their performance characteristics and is routinely monitored using BET analysis [41].

Method Validation and Quality Considerations

For regulatory applications, particularly in pharmaceutical development, proper method validation is essential for BET measurements. Under GMP conditions, method validation confirms that an analytical procedure's performance suits its intended purpose, with assessment of characteristics including specificity, accuracy, precision, limit of detection/quantification, linearity, and range [46]. A fit-for-purpose validation approach adjusts validation requirements according to the development phase, ensuring appropriate rigor without unnecessary resource expenditure [46].

For compendial methods referenced in pharmacopeias such as Ph. Eur. or USP, method verification rather than full validation is typically required. Compendial method verification confirms that the established method is suitable and reliable for its intended purpose under the specific conditions of the laboratory where it will be employed [46]. The extent of verification depends on the method type and the specific product or matrix being tested [46].

Quality control laboratories offering BET analysis services typically provide various measurement options, including multipoint surface area using nitrogen or krypton gas (following ISO 9277), specific surface area measurements according to ASTM D6556, comprehensive adsorption-desorption isotherms, high-resolution micropore analysis, and specialized isotherms using alternative gases like CO₂ or at user-defined conditions [14]. These standardized approaches ensure reproducibility and reliability of BET measurements across different laboratories and applications.

Static Volumetric Chemisorption for Active Site and Metal Dispersion Analysis

Static volumetric chemisorption is a foundational technique in heterogeneous catalysis research for quantitatively determining the number of active sites on catalyst surfaces and calculating metal dispersion. This method operates under high-vacuum conditions where precise pressure-volume-temperature (P-V-T) measurements allow accurate quantification of gas molecules strongly chemisorbed onto active metal sites [47]. Unlike physical adsorption (physisorption) which involves weak van der Waals forces, chemisorption involves the formation of strong chemical bonds through electron sharing between the adsorbate gas and the solid catalyst surface, typically with heats of adsorption ranging from 80-800 kJ/mole [48]. This strong, specific interaction forms at most a monolayer, making it ideal for counting surface active sites [49] [48].

Within the broader context of physisorption and chemisorption measurement methods research, static volumetric chemisorption provides complementary information to physical adsorption techniques. While physisorption characterizes the total surface area and porous structure of catalyst supports, chemisorption selectively probes only the catalytically active surfaces capable of forming chemical bonds with specific probe molecules [48]. This selectivity makes it indispensable for determining structure-activity relationships in catalyst design and evaluation.

Theoretical Principles

Fundamental Mechanism