The Essential Glossary of Heterogeneous Catalysis: From Fundamental Terms to Advanced Applications in Research and Drug Development

This comprehensive glossary provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an authoritative reference for terminology used in heterogeneous catalysis.

The Essential Glossary of Heterogeneous Catalysis: From Fundamental Terms to Advanced Applications in Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This comprehensive glossary provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an authoritative reference for terminology used in heterogeneous catalysis. It bridges foundational concepts—such as adsorption, active sites, and reaction mechanisms—with modern methodological applications, including the use of nanoalloys and Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) in catalytic design. The guide further addresses critical troubleshooting aspects like catalyst deactivation and poisoning, and explores advanced validation techniques such as high-throughput screening and benchmarking. By synthesizing classic principles with cutting-edge trends like single-atom catalysis and data-driven catalyst design, this resource aims to enhance interdisciplinary communication and accelerate innovation in catalytic processes relevant to pharmaceutical synthesis and biomedical research.

Core Principles and Fundamental Terminology of Heterogeneous Catalysis

Heterogeneous catalysis is a foundational concept in chemical technology, defined as a catalytic process where the catalyst exists in a different phase from the reactants [1] [2]. This phase distinction stands in contrast to homogeneous catalysis, where catalysts and reactants share the same phase, typically liquid [3]. The physical separation between the catalyst and reactants provides unique mechanical advantages while introducing specific kinetic considerations that have profound implications for industrial chemical processing [4].

In practical applications, heterogeneous catalysts are most frequently solid materials, while reactants are in gaseous or liquid phases [1] [5]. This configuration is particularly advantageous for large-scale industrial processes where catalyst separation and reuse are critical for economic viability [3]. The strategic importance of heterogeneous catalysis is underscored by its involvement in approximately 35% of the world's GDP and its role in producing 90% of chemicals by volume [1].

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Core Definition and Phase Distinctions

The defining characteristic of heterogeneous catalysis is the existence of a phase boundary between the catalyst and reactants [6]. This boundary creates an interface where catalytic phenomena occur through a sequence of molecular events [1]. The process can be visualized as a "bridge" that lowers the energy barrier for chemical transformations without the catalyst itself being consumed in the process [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Catalysis Types

| Characteristic | Heterogeneous Catalysis | Homogeneous Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Phase relationship | Catalyst and reactants in different phases | Catalyst and reactants in same phase |

| Typical catalyst form | Solid | Liquid (dissolved) |

| Separation process | Simple filtration or centrifugation | Complex distillation or extraction |

| Industrial applicability | Large-scale continuous processes | Fine chemicals and pharmaceuticals |

| Resistance to harsh conditions | Generally high | Generally limited |

The Catalytic Cycle: Adsorption, Reaction, and Desorption

The mechanism of heterogeneous catalysis follows a well-established sequence of steps that occur at the catalyst surface [1] [6]:

- Adsorption: Reactant molecules attach to the catalyst surface [1]. This initial bonding is crucial for concentrating reactants and activating them for reaction.

- Surface Reaction: Adsorbed reactants undergo chemical transformation into products through interactions with active sites [6].

- Desorption: Product molecules release from the catalyst surface, freeing active sites for subsequent reaction cycles [1].

Two distinct adsorption mechanisms operate in heterogeneous catalysis. Physisorption involves weak van der Waals forces with energies of 3-10 kcal/mol, where the adsorbate's electronic structure remains largely unchanged [1]. In contrast, chemisorption involves stronger chemical bond formation with energies of 20-100 kcal/mol, significantly altering the electronic structure of the adsorbate and creating precursor states for reaction [1].

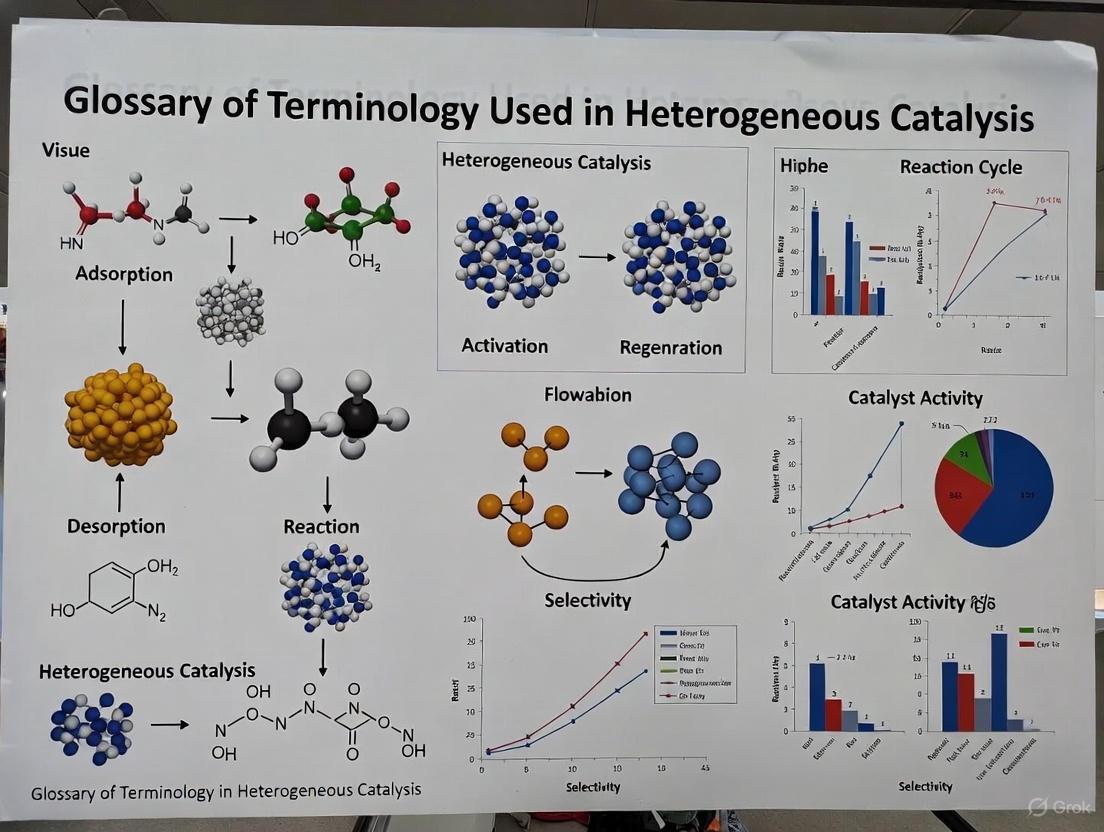

Figure 1: The Heterogeneous Catalytic Cycle. This continuous process demonstrates the sequential steps of reaction and catalyst regeneration.

Two principal mechanisms describe surface reactions. The Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism involves reaction between two adsorbed species on the catalyst surface, while the Eley-Rideal mechanism describes reaction between an adsorbed species and a non-adsorbed reactant from the fluid phase [1]. Most heterogeneously catalyzed reactions follow the Langmuir-Hinshelwood pathway [1].

Catalyst Design and Characterization

Active Sites and the Sabatier Principle

The concept of active sites is fundamental to heterogeneous catalysis, referring to specific locations on the catalyst surface where catalytic reactions primarily occur [6]. These sites represent only a fraction of the total surface area and possess distinct geometric and electronic properties that enable them to facilitate chemical transformations [4].

The Sabatier principle governs catalyst design by establishing that optimal catalytic activity requires an intermediate strength of interaction between catalyst surface and reactants [1] [4]. If the interaction is too weak, reactants fail to activate; if too strong, products cannot desorb, poisoning the surface [1]. This principle finds quantitative expression in volcano plots, which correlate reaction rates with adsorption energies [1] [4].

Modern catalyst design employs scaling relations between adsorption energies of different intermediates to reduce the dimensionality of the optimization problem [1]. A significant challenge involves "breaking" these scaling relations to access unprecedented combinations of adsorption properties that would enable superior catalytic performance [1].

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive catalyst characterization employs multiple analytical techniques to understand structure-activity relationships:

Table 2: Essential Catalyst Characterization Methods

| Technique | Acronym | Information Obtained | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brunauer-Emmett-Teller Analysis | BET | Surface area, pore size distribution | Assessing mass transport properties [6] |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy | XPS | Elemental composition, oxidation states | Identifying chemical nature of active sites [6] [7] |

| X-ray Diffraction | XRD | Crystalline phases, crystallite size | Determining catalyst structure [6] |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy | TEM | Morphology, particle size, active component dispersion | Visualizing catalyst nanostructure [6] |

| Near-Ambient Pressure XPS | NAP-XPS | Surface composition under reaction conditions | Studying catalyst dynamics during operation [7] |

The Phase Boundary Concept in Catalyst Design

Emerging perspectives suggest that optimal catalytic performance frequently occurs at phase boundaries rather than within stable phases [8]. These boundaries represent regions of particular instability where catalysts can preferably coexist in multiple states, with rapid interconversion potentially driving catalytic turnovers [8].

This paradigm shift emphasizes designing catalysts that operate at boundaries between different adsorbate coverages, stoichiometries, physical structures, or electronic structures [8]. For instance, industrial catalysts for methanol synthesis and Fischer-Tropsch reactions appear to function optimally at specific phase boundaries [8]. Theoretical models should therefore incorporate grand canonical treatments under realistic conditions to reverse-engineer conditions that position the system at desired boundaries for catalysis [8].

Experimental Methodologies in Heterogeneous Catalysis Research

Standardized Catalyst Testing Protocols

Rigorous experimental procedures are essential for generating reliable, reproducible catalytic data [7]. The following methodology, adapted from alkane oxidation studies, exemplifies a comprehensive approach to catalyst evaluation:

Catalyst Activation Protocol:

- Rapid Activation: Fresh catalysts undergo 48-hour exposure to harsh conditions (temperature up to 450°C) where conversion of either alkane or oxygen reaches approximately 80%, quickly establishing a steady-state catalyst [7].

- Kinetic Analysis Sequence:

- Temperature Variation: Determine activation energies and optimal temperature ranges [7].

- Contact Time Variation: Establish residence time effects on conversion and selectivity [7].

- Feed Variation: Systematically modify reactant ratios and introduce intermediates or steam to understand reaction network dependencies [7].

Data Quality Assurance: Implementation of "experimental handbooks" that standardize procedures across laboratories ensures consistent accounting for catalyst dynamics during data generation [7]. This approach minimizes subjective bias and enables meaningful comparison between different catalytic systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Materials and Their Functions

| Material/Reagent | Function in Catalytic Research | Representative Application |

|---|---|---|

| Vanadyl pyrophosphate (VPP) | Redox-active catalyst for selective oxidation | n-butane oxidation to maleic anhydride [7] |

| MoVTeNbOx mixed oxides | Complex multi-metal oxide catalyst | Propane oxidation to acrylic acid [7] |

| Platinum-group metals (Pt, Pd, Rh) | Oxidation catalysts for emission control | Automotive catalytic converters [5] |

| Iron-based catalysts | Ammonia synthesis | Haber-Bosch process [5] |

| Zeolite materials | Acid catalysts with shape selectivity | Fluid catalytic cracking in petroleum refining [9] |

| Vanadium/Manganese oxides | Redox-active elements for oxidation | Ethane, propane, and n-butane oxidation [7] |

Industrial Significance and Applications

Major Industrial Processes

Heterogeneous catalysis enables numerous large-scale industrial transformations that underpin modern society:

Haber-Bosch Process: Utilizing iron-based catalysts, this process converts nitrogen and hydrogen into ammonia at high temperatures and pressures [5]. The ammonia produced is primarily used for fertilizer production, supporting global agricultural systems [5]. Recent research reveals that under industrial conditions (650-850K, 10-300 bar), the Fe(111) surface becomes highly dynamic, with active sites continuously forming and disappearing [10].

Petroleum Refining: Fluid catalytic cracking employs zeolite catalysts to break heavy hydrocarbon molecules into gasoline, diesel, and other valuable products [5]. This process maximizes yield from crude oil while improving fuel quality [5].

Emission Control: Catalytic converters in vehicles use platinum, palladium, and rhodium to oxidize carbon monoxide and unburned hydrocarbons while reducing nitrogen oxides to harmless nitrogen [5]. This application has significantly improved urban air quality worldwide [5].

Methanol Synthesis: Copper-zinc oxide catalysts facilitate carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide hydrogenation to methanol [8]. Optimal performance occurs at specific coverage boundaries (approximately 0.2 ML) where the catalyst can access multiple relevant states [8].

Economic and Environmental Impact

The economic significance of heterogeneous catalysis is profound, influencing approximately 35% of global GDP through its role in producing fuels, chemicals, and materials [1]. Environmental applications have enabled substantial progress in pollution control, particularly through catalytic emission treatment systems [5].

Emerging applications in renewable energy and biomass conversion further expand the environmental contributions of heterogeneous catalysis [9]. The development of nanostructured catalysts with enhanced surface areas and reactivity supports greener production methods across multiple industrial sectors [5].

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Persistent Challenges in Industrial Practice

Despite its maturity, heterogeneous catalysis faces several significant challenges in industrial implementation:

Catalyst Deactivation: Chemical poisoning, sintering, fouling, coking, and vapor-solid reactions cause gradual performance decline, costing industry billions annually in process shutdowns and catalyst replacement [1] [3]. For example, sulfur compounds poison Cu/ZnO catalysts in methanol production [1].

Mass Transfer Limitations: Reactant access to active sites and product removal can become rate-limiting, particularly with poorly designed pore structures [3]. These transport phenomena often mask intrinsic catalytic activity in practical applications [4].

Thermal Stability: High operating temperatures can induce sintering, where catalyst particles coalesce and reduce active surface area [3]. Maintaining structural integrity under harsh conditions remains challenging for many catalytic materials [3].

Scalability Issues: Translating laboratory-optimized catalysts to industrial scale presents difficulties in replicating conditions, with differences in mixing, heat transfer, and mass transfer complicating scale-up efforts [3].

Emerging Solutions and Research Directions

Single-Cluster Catalysis: Supported atomic clusters offer enhanced selectivity and activity through precise molecular control [3]. Their high dispersion improves mass transfer efficiency while maintaining thermal stability under demanding conditions [3].

Dynamic Catalyst Design: Recognizing that catalysts transform under reaction conditions has shifted focus toward designing systems that dynamically evolve to active states [8] [10] [7]. The "phase boundary" perspective encourages targeting metastable states that optimize specific catalytic functions [8].

Data-Centric Approaches: Artificial intelligence and machine learning analyze complex property-function relationships, identifying key "materials genes" that govern catalytic performance [7]. Symbolic regression techniques derive interpretable analytical expressions from high-quality experimental data, providing design rules for improved catalysts [7].

Advanced Simulation Methods: Combining machine learning potentials with enhanced sampling techniques enables realistic modeling of catalytic processes under industrial conditions [10]. These approaches reveal the profound influence of surface dynamics on catalytic activity, explaining why low-temperature studies often fail to predict operational performance [10].

Figure 2: Modern Catalyst Development Workflow. This iterative process integrates characterization, testing, and data analysis to inform catalyst design.

The future of heterogeneous catalysis research lies in embracing complexity and dynamics rather than searching for static optimal compositions [8] [10]. Understanding how catalysts function at phase boundaries under realistic conditions will enable more rational design strategies, reducing reliance on serendipitous discovery that has historically dominated the field [8].

In heterogeneous catalysis, where the catalyst is in a different phase than the reactants, adsorption is the foundational step that initiates the catalytic cycle [1]. It is the process by which atoms, ions, or molecules from a gas or liquid phase (the adsorbate) accumulate on the surface of a solid (the adsorbent) [11]. This surface phenomenon results in the formation of a molecular or atomic film, bringing the reactant molecules into close proximity with the catalyst's active sites and preparing them for chemical transformation [11] [1]. The catalytic process can be generalized as a sequence of steps: diffusion of reactants to the surface, adsorption of at least one reactant, reaction on the surface, desorption of the products, and diffusion of products away from the surface [12]. The efficiency of this cycle is profoundly influenced by the nature of the adsorption interaction, which can be broadly classified into two distinct types: physisorption (physical adsorption) and chemisorption (chemical adsorption) [12] [1]. A critical concept that bridges these two phenomena, particularly in the context of reaction kinetics, is the precursor state [1]. Understanding the differences between these adsorption mechanisms is essential for researchers and scientists designing catalysts for applications ranging from large-scale chemical production to drug development.

Distinguishing Physisorption and Chemisorption

Physisorption and chemisorption are differentiated by the nature of the forces involved, their strength, and their specificity. Physisorption is the result of relatively weak, nonspecific van der Waals forces, which include dipole-dipole interactions, induced dipole interactions, and London dispersion forces [12] [1]. No chemical bonds are formed in this process, and the electronic states of the adsorbate and adsorbent remain largely unperturbed. The binding energies involved are typically low, ranging from 3 to 10 kcal/mol, making physisorption a readily reversible process [1]. A key characteristic of physisorption is that it can form multiple layers on the adsorbent surface, as the adsorbate-adsorbate interactions are similar to the adsorbate-adsorbent interactions [12].

In contrast, chemisorption involves the formation of much stronger chemical bonds through the sharing of electrons between the adsorbate and the adsorbent, which can be regarded as the formation of a surface compound [12] [1]. This process is highly specific, occurring only between certain adsorptive and adsorbent species, and typically requires that the catalytic surface is clean of previously adsorbed molecules [12]. The energies involved are significantly higher, ranging from 20 to 100 kcal/mol, and in some cases, for bonds like C-N, can reach up to 600 kJ/mol [12]. Due to this strong, specific bond formation, chemisorption is inherently a single-layer (monolayer) process and is often difficult to reverse [12]. In many catalytic systems, both processes can occur simultaneously, such as a layer of molecules physically adsorbed on top of an underlying chemisorbed layer [12]. Furthermore, the same surface can exhibit physisorption at lower temperatures and chemisorption at higher temperatures, as seen with nitrogen on iron [12].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Physisorption and Chemisorption

| Characteristic | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Forces | Weak van der Waals forces (dipole-dipole, induced dipole, dispersion) [1] | Strong chemical bonds (electron sharing) [1] |

| Binding Energy | 3–10 kcal/mol (typical) [1] | 20–100 kcal/mol (can be higher) [12] [1] |

| Reversibility | Easily reversible [12] | Difficult to reverse, often irreversible [12] |

| Layer Formation | Multi-layer formation possible [12] | Typically limited to a single monolayer [12] |

| Specificity | Non-specific; occurs on all surfaces under suitable conditions [12] | Highly selective; requires specific adsorbent-adsorbate pairs [12] |

| Role in Catalysis | Concentrates reactants at the surface; precursor to chemisorption [1] | Essential step; forms reactive surface intermediates [12] |

The Precursor State in Adsorption Kinetics

In the kinetics of heterogeneous catalysis, the journey of a gas-phase molecule to becoming chemisorbed often involves an intermediate energy state known as the precursor state [1]. This state is characterized by an initial physisorption of the reactant molecule onto the catalyst surface before it transitions into a chemisorbed state. From this precursor state, the molecule has several possible pathways: it can undergo chemisorption if it finds an active site and possesses sufficient energy, it can desorb back into the bulk fluid phase, or it can migrate along the surface to find a more favorable site for reaction [1]. The nature and lifetime of this precursor state can significantly influence the overall observed reaction kinetics, as it affects the probability of a reactant molecule successfully finding and binding to an active site [13] [1]. The Lennard-Jones potential model provides a fundamental theoretical framework for understanding the energy landscape and molecular interactions that define this transition from physisorption to chemisorption as a function of atomic separation [1].

Diagram 1: The adsorption pathway, showing the precursor state as an intermediate physisorbed state before chemisorption and surface reaction. From the precursor state, molecules can proceed to chemisorption or desorb back into the gas phase.

Experimental Methods for Characterizing Adsorption

The accurate characterization of adsorption processes is critical for catalyst development and evaluation. Analytical techniques based on gas sorption provide indispensable tools for probing surface structure and chemistry [12]. The relationship between the quantity of molecules adsorbed and the pressure at a constant temperature, known as the adsorption isotherm, is a primary source of information [12]. Physical adsorption isotherms are used to characterize the overall surface and porosity of catalyst supports, revealing total surface area, mesopore and micropore volume and area, and pore size distribution [12]. In contrast, chemical adsorption isotherms are selective, probing only the active areas of the surface capable of forming a chemical bond with a specific probe molecule [12].

Isothermal Chemisorption Techniques

Isothermal chemisorption analyses are conducted using two main techniques. The static volumetric method involves exposing a cleaned catalyst sample to an adsorptive gas in a closed chamber at a constant temperature. The quantity adsorbed is determined by precise measurements of pressure changes as known doses of gas are sequentially added to the system until equilibrium is reached at each point, building a high-resolution isotherm [12]. This method is well-suited for measurements from very low pressures to atmospheric pressure. The dynamic flowing-gas (pulse chemisorption) technique operates at ambient pressure. Here, small, accurately known quantities of adsorptive are injected in pulses into a carrier gas stream flowing over the catalyst sample. A thermal conductivity detector (TCD) monitors the quantity of adsorptive not adsorbed by the catalyst. The adsorbed quantity is calculated by summing the uptake from each injection until the sample is saturated [12]. This method is particularly suitable for determining the total active metal surface area of a catalyst.

Temperature-Programmed Techniques

Temperature-programmed methods have become indispensable for catalyst characterization [12]. In Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD), also known as Thermal Desorption Spectroscopy (TDS), a catalyst surface with pre-adsorbed molecules is heated in a controlled, linear fashion while the desorbing species are monitored, typically with a mass spectrometer or TCD [13]. The temperature at which desorption peaks occur provides information about the binding strength and the distribution of adsorption sites. Related techniques include Temperature-Programmed Reduction (TPR), where a catalyst precursor (e.g., a metal oxide) is heated in a reducing gas stream to determine its reducibility, and Temperature-Programmed Oxidation (TPO), used to study catalyst regeneration or coke burning [12].

Table 2: Key Analytical Techniques for Studying Adsorption Processes

| Technique | Primary Function | Key Measurements | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volumetric Chemisorption [12] | Measure gas uptake at constant temperature | High-resolution adsorption isotherm; active metal surface area; active site density | Catalyst design and production evaluation; fundamental adsorption studies |

| Pulse Chemisorption [12] | Measure gas uptake at ambient pressure | Total metal dispersion; active metal surface area | Quality control; rapid assessment of catalyst capacity |

| Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD) [12] [13] | Probe strength of adsorbate binding | Desorption energy; binding strength; surface site heterogeneity | Characterization of acid/base sites; study of adsorption/desorption kinetics |

| Gas Chromatography (GC) [13] | Quantify adsorbed/desorbed species | Concentration of adsorbed volatiles; desorption efficiency | Evaluation of filter durability; analysis of VOC adsorption/desorption [13] |

Diagram 2: A generalized experimental workflow for characterizing adsorption, showing the main analytical pathways following sample preparation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental study of adsorption, as cited in this work, relies on a set of essential materials and reagents. The following table details key components used in the featured research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Adsorption Studies

| Material / Reagent | Function in Experiment | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Alkanethiol Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) [14] | Well-defined model surfaces with specific terminal functional groups (e.g., -OH, -CH₃, -NH₂, -COOH) | Studying peptide-surface interactions and measuring standard state adsorption free energy (ΔG°ads) [14] |

| Host-Guest Peptides (TGTG-X-GTGT) [14] | Model biomolecules with a variable amino acid residue to probe specific residue-surface interactions | Generating a benchmark dataset for amino acid residue adsorption on functionalized surfaces [14] |

| Porous Zeolite Filters (e.g., ZSM-11) [13] | High-surface-area inorganic adsorbents with molecular-sieving properties | Adsorption and desorption studies of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs); filter reusability testing [13] |

| Probe Gases (e.g., N₂, CO, H₂) [12] [15] | Analytically selected molecules for characterizing surface properties via physisorption or chemisorption | Determining surface area and porosity (N₂ physisorption); measuring active metal surface area (CO/H₂ chemisorption) [12] |

| Transition Metal & Metal-Oxide Catalysts [15] | Catalytic materials and supports for fundamental adsorption energy measurements | High-throughput DFT and experimental studies of impurity adsorption for catalyst poisoning assessment [15] |

A precise understanding of adsorption fundamentals—clearly distinguishing between physisorption and chemisorption and appreciating the role of the precursor state—is indispensable in heterogeneous catalysis research. These concepts form the lexicon required to describe the initial, critical steps of any surface-mediated reaction. For the researcher, the selection of appropriate characterization techniques, from isothermal chemisorption to temperature-programmed methods, is paramount to elucidating the surface properties and mechanisms that govern catalytic activity, selectivity, and longevity. As catalysis continues to evolve, with new applications emerging in energy systems and life sciences, these foundational principles of adsorption will remain central to the rational design and development of next-generation catalytic materials [16].

In the specialized lexicon of heterogeneous catalysis, an active site is defined as a specific region or group of atoms on a catalyst surface that directly facilitates molecular adsorption and transformation, thereby lowering the activation energy of a chemical reaction [17]. These sites are the fundamental loci where catalytic magic occurs, and their nature is governed by both the intrinsic chemical properties of the catalytic material and its extrinsic physical structure. A related, yet distinct, concept is that of the catalyst support, a material, typically of high surface area, upon which the active catalytic phase is dispersed. The support is not merely an inert carrier; it plays a multifunctional role in modulating the catalyst's electronic properties, stabilizing nanoparticles against sintering, and often contributing directly to the catalytic activity through strong metal-support interactions [4] [18]. The efficiency of a heterogeneous catalyst is therefore not solely a function of the active phase but is an emergent property of the synergistic combination of the active site and its support.

The imperative to maximize surface area is a central tenet in catalyst design. A high surface area provides a greater density of potential active sites, enhancing the interaction between reactants and the catalyst [19] [20]. This is quantified through the specific surface area (SSA), typically measured using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method via N₂ adsorption isotherms [19]. However, the pursuit of high surface area must be balanced against other critical factors. As noted in studies on high-surface-area anatase TiO₂, materials with high SSA often suffer from low thermal stability, leading to sintering—a process where particles agglomerate and grow, resulting in a loss of surface area and active sites—particularly during necessary thermal treatments in synthesis or operation [19]. The interplay between achieving high surface area, maintaining structural and thermal stability, and ensuring the optimal electronic environment at the active site constitutes the core challenge in designing advanced catalytic systems.

The Nature and Design of Active Sites

Fundamental Classifications and Effects

Active sites in heterogeneous catalysts are not uniform; their properties and effectiveness are shaped by two primary effects: the coordination effect and the ligand effect. The coordination effect refers to the geometric arrangement of atoms surrounding the active site, which is influenced by structural features such as crystal facets, defects, steps, and corners [17]. For instance, atoms at a step or kink site on a crystal surface often have lower coordination numbers than those on a flat terrace, making them more reactive for breaking chemical bonds. The ligand effect, on the other hand, concerns the chemical identity and electronic influence of neighboring atoms [17]. In alloys or high-entropy alloys (HEAs), the random distribution of different elements adjacent to an active metal atom can significantly alter its electronic structure, and consequently, its adsorption properties for reactants and intermediates [17]. In real-world catalysts, these two effects are intertwined, creating a complex distribution of active site environments that collectively determine the catalyst's overall activity, selectivity, and stability.

The design of active sites has been revolutionized by advanced computational and machine learning approaches. Traditional "forward design" relies on establishing structure-property relationships through high-throughput density functional theory (DFT) calculations and linear scaling relationships, which often lead to "volcano plots" that identify catalysts with optimal adsorption energies [17]. A more ambitious goal is inverse design, which starts with a desired catalytic property (e.g., an optimal adsorption energy for a key intermediate) and works backward to identify the atomic-level structure that would provide it [17]. Topology-based deep generative models represent a cutting-edge tool for this purpose. These models use mathematical tools like persistent GLMY homology (PGH) to create a refined, quantitative fingerprint of a three-dimensional active site's structure, capturing nuances that are missed by simpler descriptors [17]. This allows for the interpretable inverse design of active sites, paving the way for a more rational catalyst design paradigm beyond traditional trial-and-error methods.

Characterization of Active Sites

The precise identification and quantification of active sites are crucial for understanding catalytic performance. A common experimental method involves the use of probe molecules, such as carbon monoxide (CO), analyzed via in situ infrared (IR) spectroscopy [19]. The vibrational frequency of CO adsorbed on different surface sites (e.g., on different metal atoms or at terraces vs. steps) provides a fingerprint that allows researchers to identify the nature and relative abundance of various active sites. As detailed in a study on TiO₂, the protocol involves preparing a self-supporting catalyst pellet, activating it under controlled temperature and vacuum or gas flow, and then introducing CO at specific pressures and temperatures [19]. The resulting IR spectra are processed by subtracting the background, and the different carbonyl bands are deconvoluted using curve-fitting procedures to quantify the distribution of surface sites. This methodology provides a direct, experimental link between the catalyst's surface structure and its potential chemical activity.

Table 1: Experimental Techniques for Active Site Characterization

| Technique | Measured Property | Key Information on Active Sites | Example Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO Probe IR Spectroscopy [19] | Vibrational frequency of adsorbed CO | Chemical identity & coordination of surface metal atoms | Pellet activation at 500°C under vacuum/O₂, CO dosing at LN₂ temperature, spectral deconvolution |

| Persistent Homology (PGH) [17] | Topological fingerprint of 3D atomic structure | Geometric sensitivity & correlation with adsorption properties | Generate atomic point cloud from active site, perform algebraic topological analysis, create feature vector |

| N₂ Physisorption (BET) [19] | Specific Surface Area (SSA) | Total area available for reaction & site dispersion | Outgas sample, measure N₂ adsorption isotherms at LN₂ temperature, apply BET equation |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) [19] | Crystallite size & phase | Phase-dependent active site structure & thermal stability | Collect pattern on powdered sample, apply Scherrer equation to peak broadening for crystallite size |

Figure 1: Workflow for the identification, computational analysis, and inverse design of catalytic active sites, integrating both coordination and ligand effects [17].

The Role and Engineering of Catalyst Supports

Functions and Material Classes

Catalyst supports are engineered to provide a stable, high-surface-area foundation that maximizes the dispersion of the active catalytic phase, which is often a precious metal like platinum. A high dispersion directly translates to a higher number of accessible active atoms per unit mass of precious metal, improving the cost-effectiveness and activity of the catalyst [18]. Beyond this primary function, modern support materials are designed to actively participate in the catalytic process. They can modulate the electronic structure of metal nanoparticles through strong metal-support interactions (SMSI), which can enhance intrinsic activity and selectivity [18]. Furthermore, conductive supports (e.g., carbon materials) facilitate electron transport in electrocatalytic reactions like the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), while robust oxide supports enhance thermal and mechanical stability, preventing nanoparticle agglomeration (sintering) and degradation under harsh operating conditions [4] [18].

The choice of support material is critical and depends on the application. A wide range of materials is employed, each with distinct advantages. Mesoporous carbons offer tunable pore structures and high conductivity but can be susceptible to oxidative corrosion. Graphene and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) provide exceptional electrical conductivity and high surface area. Metal oxides like titanium dioxide (TiO₂), zirconia (ZrO₂), and ceria (CeO₂) are valued for their stability and ability to engage in strong metal-support interactions [18]. The case of TiO₂ is particularly instructive: its high surface area is crucial for applications like selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NOx, but this high surface area can be rapidly lost due to sintering during thermal treatments, a process accelerated by the presence of humidity [19]. This underscores that the selection of a support is a complex trade-off between surface area, stability, and electronic properties.

Support-Driven Catalyst Architectures

Advanced support materials have enabled the development of sophisticated catalyst architectures that go beyond simple nanoparticle dispersion. These engineered structures are designed to maximize the utilization of the active phase and create synergistic effects. Key designs include:

- Core-Shell Structures: A core of one material (which may be the support or an inactive metal) is enclosed by a shell of the active catalytic metal. This structure exposes almost all atoms of the precious metal to the reactant environment, dramatically improving mass activity [18].

- Hollow Structures: These materials provide a high surface-to-volume ratio and can confine reactants in a small volume, potentially enhancing reaction rates [18].

- Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs): This architecture represents the ultimate limit of metal dispersion, where individual metal atoms are anchored to a support. SACs maximize atom efficiency and often exhibit unique catalytic properties due to the isolated, coordinatively unsaturated nature of the active sites [4] [18]. The support in SACs is critical, as its surface functional groups (e.g., defects, nitrogen dopants in carbon) are responsible for stabilizing the isolated metal atoms and preventing their migration and agglomeration.

Table 2: Common Catalyst Support Materials and Their Properties

| Support Material | Key Characteristics | Impact on Catalytic Performance | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesoporous Carbon [18] | High SSA, tunable porosity, good conductivity | Enhances metal dispersion, improves mass transport | Fuel cells, electrocatalysis |

| Graphene [18] | Ultra-high conductivity, high theoretical SSA | Excellent electron transfer, stabilizes nanoparticles/single atoms | Oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [18] | 1D morphology, high conductivity, mechanical strength | Directed electron transport, unique confinement effects | Electrochemical energy storage |

| Anatase TiO₂ [19] | High SSA (when nano-structured), strong metal-support interaction | Stabilizes active phase, prone to sintering at high T | Photocatalysis, selective catalytic reduction (SCR) |

| High-Entropy Alloys (HEAs) [17] | Vast compositional space, complex active sites | Fine-tunes adsorption energies via ligand/coordination effects | Model studies, emerging electrocatalysis |

Experimental Protocols for Support and Active Site Analysis

Protocol: Evaluating Thermal Stability of High-Surface-Area Supports

The thermal stability of a catalyst support is a critical parameter, as many catalysts undergo thermal treatments during synthesis or operation. The following protocol, adapted from a study on anatase TiO₂, provides a methodology for assessing this stability [19].

Objective: To determine the structural and textural evolution of a high-surface-area support (e.g., TiO₂) under different thermal treatment conditions.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-surface-area support material (e.g., anatase TiO₂)

- Tubular furnace or muffle furnace (static and flow conditions)

- Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA)

- N₂ Physisorption Analyzer (BET surface area)

- X-ray Powder Diffractometer (XRD)

- In situ IR cell and spectrophotometer

Methodology:

- Baseline Characterization: Begin by measuring the specific surface area (SSA) of the raw, untreated material (r-TiO₂) using N₂ adsorption at liquid nitrogen temperature and applying the BET equation. Perform XRD to determine the crystallite size along different lattice directions using the Scherrer equation [19].

- Controlled Thermal Treatments: Subject identical samples of the support to various thermal treatments:

- Static Air Calcination: Heat samples in a muffle furnace across a temperature range (e.g., 100–500 °C) for a fixed duration (e.g., 1 or 5 hours) [19].

- Flow Condition Treatment: Heat samples in a tubular furnace under a controlled flow of dry or wet air (e.g., 150 mL min⁻¹), ramping the temperature at a defined rate (e.g., 5 °C min⁻¹) [19].

- Vacuum Treatment: Outgas samples inside the physisorption analyzer at elevated temperatures (e.g., up to 450 °C) for 2 hours to assess stability in the absence of air [19].

- Post-Treatment Analysis: After each treatment, repeat the SSA and XRD measurements. Monitor the change in SSA and crystallite growth as a function of treatment type, temperature, and atmosphere.

- Surface Site Investigation: Use in situ IR spectroscopy with a probe molecule like CO. Prepare self-supporting pellets of the samples treated at different conditions. Activate the pellets at high temperature (e.g., 500 °C) under dynamic vacuum. After cooling, introduce CO and collect IR spectra. The resulting carbonyl bands reveal changes in the abundance and nature of surface sites (e.g., Lewis acid sites) after thermal aging [19].

Interpretation: Treatments that best preserve the original SSA and minimize crystallite growth indicate superior thermal stability. Flow conditions often provide better stability than static air, while the presence of humidity typically accelerates sintering. The IR data provides a direct link between textural changes and the loss of specific surface functionalities.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Support and Active Site Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Molecules (CO, NH₃) [19] | Characterization of surface acid sites and active sites | Identifying and quantifying Lewis/Brønsted acid sites via IR spectroscopy |

| High-Surface-Area Metal Oxides (e.g., Anatase TiO₂) [19] | Model catalyst support | Studying metal-support interactions and thermal stability |

| Carbon Supports (Graphene, CNTs) [18] | Conductive catalyst support | Dispersing Pt nanoparticles for electrocatalytic ORR |

| Ammonium Metavanadate [19] | Precursor for active phase | Preparing VOx/TiO₂ catalysts for SCR of NOx |

| Single-Atom Catalyst (SAC) Precursors [4] | Creating atomically dispersed active sites | Synthesizing Pt1/C catalysts for maximum atom utilization |

Figure 2: Multifunctional roles of a catalyst support in enhancing the overall performance of a catalytic system [4] [18].

The strategic design of active sites and the engineering of catalyst supports are deeply interconnected disciplines central to advancing heterogeneous catalysis. The pursuit of maximum surface area, while crucial for achieving high active site density, must be intelligently balanced against the imperative for long-term thermal and structural stability. The modern catalyst designer has at their disposal a powerful suite of tools, ranging from topological descriptors for the inverse design of optimal active site geometries [17] to advanced experimental protocols for evaluating the stability of high-surface-area supports [19]. The emerging paradigm moves beyond viewing the support as a passive scaffold to treating it as an integral, active component of the catalytic system. This holistic approach, which considers the synergistic effects between the active phase and its support, is key to developing next-generation catalysts with unparalleled efficiency, selectivity, and durability for energy and chemical transformations.

Heterogeneous catalysis, a process where the catalyst exists in a different phase than the reactants, is fundamental to approximately 35% of the world's GDP and involved in the production of 90% of chemicals by volume [1]. These catalytic processes occur through sequences of reactions involving fluid-phase reagents and the exposed layer of the solid catalyst surface, with thermodynamics, mass transfer, and heat transfer influencing the reaction kinetics [1]. The foundational work of Irving Langmuir in the early 20th century established the basic principles of surface chemistry that underpin our modern understanding of these processes [21]. Within this framework, two principal mechanisms describe how reactions proceed on surfaces: the Langmuir-Hinshelwood (L-H) mechanism and the Eley-Rideal (E-R) mechanism, each with distinct characteristics and kinetic profiles that dictate their applicability to specific catalytic systems.

The core of heterogeneous catalysis lies in the adsorption of reactants onto the catalyst surface, which can occur through physisorption (weak binding via van der Waals forces with energies of 3-10 kcal/mol) or chemisorption (strong binding through chemical bond formation with energies of 20-100 kcal/mol) [1]. In chemisorption, molecules may remain intact or dissociate, with the barrier to dissociation significantly affecting the adsorption rate [1]. These adsorption processes create precursor states that enable subsequent surface reactions, with the nature of these states profoundly influencing the overall reaction kinetics [1]. The Langmuir-Hinshelwood and Eley-Rideal mechanisms represent two fundamentally different pathways by which these surface reactions can proceed, each with characteristic kinetic signatures and implications for catalyst design and operation.

The Langmuir-Hinshelwood Mechanism

Conceptual Foundation and Historical Development

The Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism, first proposed by Irving Langmuir in 1921 and further developed by Cyril Hinshelwood in 1926, describes a surface reaction process where two adsorbed reactants undergo a bimolecular reaction on the catalyst surface [22]. This mechanism originally focused on bimolecular reactions involving two kinds of molecules adsorbed at the same surface sites, with the surface reaction serving as the rate-determining step [23]. In its classic formulation, the L-H mechanism requires both reactants to adsorb onto neighboring active sites on the catalyst surface before reacting while both are in thermal equilibrium with the surface [23]. The catalytic oxidation of CO on Pt(111) represents a classic example of a reaction proceeding via the L-H mechanism, involving the chemisorption of CO, dissociative adsorption of O₂, surface reaction between CO and O to form CO₂, and final desorption of CO₂ [23].

The term "Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism" has sometimes been broadly applied in photocatalytic literature when a linear reciprocal relation is observed between the reaction rate and substrate concentration, consistent with Langmuir-type adsorption kinetics [23]. However, the original meaning in catalysis specifically refers to bimolecular surface reactions, distinguishing it from monomolecular surface processes [23]. True validation of the L-H mechanism requires demonstrating that the adsorption equilibrium constant obtained kinetically matches that measured from dark adsorption experiments, ensuring that the observed kinetics genuinely result from Langmuirian adsorption behavior [23].

Mathematical Formulation and Kinetic Analysis

The kinetic formulation of the Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism for a bimolecular reaction A + B → Products follows a sequence of elementary steps [22]:

- A + S ⇌ AS (adsorption of A)

- B + S ⇌ BS (adsorption of B)

- AS + BS → Products (surface reaction)

The rate equation for this mechanism derives from the assumption that the surface reaction between the two adsorbed species is the rate-determining step. The resulting rate expression is:

[ r = k CS^2 \frac{K1K2CACB}{(1 + K1CA + K2C_B)^2} ]

Where (r) is the reaction rate, (k) is the surface reaction rate constant, (CS) is the surface site concentration, (K1) and (K2) are the adsorption equilibrium constants for A and B respectively, and (CA) and (C_B) are the concentrations of A and B [22].

The kinetic behavior varies significantly depending on the concentration regime and relative adsorption strengths [22]:

Table: Langmuir-Hinshelwood Rate Dependence on Concentration Conditions

| Condition | Rate Expression | Reaction Order |

|---|---|---|

| Low adsorption of both reactants | ( r = k CS^2 K1K2CAC_B ) | First order in A and B |

| Low adsorption of A, high adsorption of B | ( r = k CS^2 \frac{K1K2CACB}{(1 + K1C_A)^2} ) | Complex dependence |

| High adsorption of both reactants | ( r = k CS^2 \frac{K2CB}{K1C_A} ) | Inverse first order in A |

For photocatalytic reactions following L-H kinetics, the rate expression is often simplified to:

[ r = \frac{ksKC}{KC + 1} ]

Where (r) is the reaction rate, (k) is the rate constant of the surface reaction, (K) is the adsorption equilibrium constant, (s) is the limiting amount of surface adsorption, and (C) is the substrate concentration [23]. This equation predicts a linear relationship between the reciprocal of the reaction rate and the reciprocal of concentration, which serves as common experimental evidence for L-H kinetics in photocatalytic systems [23].

Experimental Validation and Methodologies

Establishing that a reaction follows the Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism requires rigorous experimental validation beyond simple kinetic fitting. The following methodological approach provides a comprehensive verification protocol:

Adsorption Isotherm Measurement: Conduct dark adsorption experiments (without reaction) to determine the adsorption equilibrium constant (K) and maximum adsorption capacity [23]. This provides an independent measure of adsorption parameters for comparison with kinetic data.

Kinetic Parameter Determination: Perform reaction rate measurements across a wide concentration range. Create both Lineweaver-Burk plots (1/r vs. 1/C) and concentration-to-rate ratio plots (C/r vs. C) to extract kinetic parameters ks and K [23].

Parameter Consistency Verification: Compare the adsorption equilibrium constant K obtained from kinetic analysis with that determined from dark adsorption measurements. The L-H mechanism is only validated if these values agree within experimental error [23].

Light Intensity Studies: For photocatalytic systems, verify "light-intensity limited" conditions where photoabsorption represents the rate-determining step rather than adsorption/desorption processes [23].

Surface Coverage Monitoring: Use techniques like in-situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) to directly monitor surface coverage during reaction and confirm the coexistence of both adsorbed species [24].

This experimental protocol ensures that observed Langmuir-type kinetics genuinely result from the L-H mechanism rather than other pathways that might produce similar kinetic patterns. Particular attention should be paid to the consistency between adsorption equilibria measured in dark conditions and those derived from kinetic analysis, as discrepancies invalidate the L-H assignment [23].

The Eley-Rideal Mechanism

Conceptual Foundation and Historical Context

The Eley-Rideal mechanism proposes a fundamentally different pathway for surface reactions, where a gas-phase reactant directly interacts with an adsorbed species without undergoing adsorption itself [24]. This mechanism was initially studied by Eley and Rideal approximately 75 years ago, though the broader concept of a reaction between a chemisorbed molecule and a gaseous colliding molecule had been previously suggested by Langmuir [25]. In the E-R mechanism, only one reactant adsorbs onto the catalyst surface and achieves thermal equilibrium with it, while the second reactant approaches from the gas phase and reacts directly with the adsorbed species in a "nonthermal surface reaction" where the gas-phase molecule may not equilibrate with the surface temperature [23] [22].

The hydrogenation of ethane on a nickel catalyst (C₂H₂ + 2Hₐd → C₂H₄) represents an early example of a reaction following the Eley-Rideal mechanism [23]. Interestingly, some scholars argue that the reaction between a chemisorbed molecule and a gaseous molecule should more accurately be termed the "Langmuir-Rideal mechanism," as Langmuir originally proposed this type of interaction alongside the reaction between two chemisorbed molecules [25]. The specific case examined by Eley and Rideal has particular importance in both heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysis in the liquid-phase, where it relates to outer-sphere reactions [25].

Mathematical Formulation and Kinetic Analysis

The Eley-Rideal mechanism for a reaction A + B → Products involves two fundamental steps [22]:

- A(g) + S(s) ⇌ AS(s) (adsorption of A)

- AS(s) + B(g) → Products (reaction with gas-phase B)

The rate expression for this mechanism derives from the assumption that the reaction between the adsorbed A and gas-phase B is the rate-determining step:

[ r = k CS CB \frac{K1CA}{K1CA + 1} ]

Where (r) is the reaction rate, (k) is the surface reaction rate constant, (CS) is the surface site concentration, (CA) and (CB) are the concentrations of A and B, and (K1) is the adsorption equilibrium constant for A [22].

This rate equation exhibits distinctive kinetic behavior:

Table: Eley-Rideal Rate Dependence on Concentration Conditions

| Condition | Rate Expression | Reaction Order |

|---|---|---|

| Low concentration of A | ( r = k CS K1CACB ) | First order in A and B |

| High concentration of A | ( r = k CS CB ) | Zero order in A, first order in B |

The Eley-Rideal mechanism is particularly relevant in environmental catalysis applications. For example, the oxidation of gaseous Hg⁰ in the presence of HCl often follows an E-R pathway, where HCl first adsorbs and decomposes into active chlorine species (Cl*), which then react with gaseous Hg⁰ to form HgCl, with subsequent reactions producing HgCl₂ [24]. Similarly, the removal of Hg⁰ on magnetic adsorbents in the presence of H₂S proceeds via E-R mechanism, where H₂S decomposes to active S₂²⁻ species that convert Hg⁰ into HgS [24].

Experimental Validation and Methodologies

Distinguishing the Eley-Rideal mechanism from Langmuir-Hinshelwood requires specific experimental approaches:

Pre-adsorption Experiments: Pre-adsorb species A on the catalyst surface, then expose to gas-phase B in the absence of gaseous A. Reaction observation confirms E-R pathway [24].

Surface Coverage Variation: Measure reaction rate as a function of surface coverage of A (θ_A). Unlike L-H kinetics which show a maximum then decrease at high coverage due to site blocking, E-R kinetics continue to increase with coverage as no additional sites are needed for B [23].

Temperature Dependence Studies: Eley-Rideal reactions may exhibit different temperature dependencies as one reactant remains non-thermalized with the surface [23].

Isotopic Labeling: Use isotopically labeled gas-phase reactants to track reaction pathways and distinguish between E-R and L-H mechanisms.

In-situ Spectroscopy: Apply techniques like DRIFTS to confirm the absence of adsorbed B during reaction while detecting reaction intermediates [24].

For Hg⁰ oxidation systems, mechanistic assignment (E-R vs. L-H) can be determined based on surface analysis of catalysts exposed to oxidants like HCl, followed by mercury oxidation in the absence of gaseous HCl [24]. Reaction systems including Hg⁰ oxidation by HBr on V₂O₅/TiO₂-SCR catalyst, Hg⁰ oxidation by HCl over CeW/Ti catalysts and V₂O₅/TiO₂(001), and Hg⁰ oxidation by H₂S over MnO₂(110) have been shown to occur via the E-R mechanism [24].

Comparative Analysis and Mechanistic Distinction

Direct Comparison of Key Characteristics

The fundamental differences between Langmuir-Hinshelwood and Eley-Rideal mechanisms manifest in multiple aspects of their reaction pathways and kinetic behaviors:

Table: Comprehensive Comparison of L-H and E-R Mechanisms

| Characteristic | Langmuir-Hinshelwood | Eley-Rideal |

|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Requirement | Both reactants must adsorb | Only one reactant adsorbs |

| Nature of Reaction | Thermal reaction between adsorbed species | Nonthermal reaction with gas-phase participant |

| Surface Site Requirement | Two adjacent sites needed | Single site sufficient |

| Rate-Determining Step | Surface reaction between adsorbed species | Reaction between adsorbed and gas-phase species |

| Typical Rate Expression | ( r = k CS^2 \frac{K1K2CACB}{(1+K1CA+K2C_B)^2} ) | ( r = k CS CB \frac{K1CA}{K1CA+1} ) |

| Coverage Dependence | Rate peaks then decreases at high coverage | Rate increases continuously with coverage |

| Temperature Effects | Both reactants thermalized with surface | Gas-phase reactant may not be thermalized |

Diagnostic Kinetic Plots and Mechanistic Assignment

Experimental discrimination between these mechanisms relies on systematic variation of reactant concentrations and surface coverage:

Coverage Variation Experiments: As shown in Figure 4, the reaction rate dependence on surface coverage of A (θA) provides a definitive diagnostic tool [23]. For the L-H mechanism, the rate initially increases with coverage, reaches a maximum when surface sites are optimally occupied, then decreases as high coverage of A blocks adsorption sites for B, eventually dropping to zero at θA = 1 [23]. In contrast, the E-R mechanism shows a continuously increasing rate with θ_A since B does not require adsorption sites, proceeding directly to a plateau at full coverage [23].

Concentration Variation Studies: Methodical variation of reactant concentrations with analysis of reaction orders provides additional discrimination power. The L-H mechanism typically shows complex concentration dependence with fractional or changing reaction orders, while E-R kinetics maintain simpler integer orders (zero or first order) depending on concentration regimes [22].

Graphical Analysis: Linearization plots offer complementary evidence. L-H kinetics often show linearity in reciprocal plots (1/r vs. 1/C), while E-R mechanisms may display different linearization characteristics [23]. However, kinetic analysis alone cannot conclusively establish mechanism without supporting adsorption studies [23].

Visualization of Reaction Mechanisms

Langmuir-Hinshelwood Mechanism Diagram

Eley-Rideal Mechanism Diagram

Coverage-Rate Dependence Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Catalyst Characterization Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Mechanism Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Metal-doped Zeolites (Cu/SSZ-13, Fe-ZSM-5) | Provide well-defined active sites for adsorption and reaction | NH₃-SCR reactions, mechanistic studies of L-H vs E-R pathways [24] |

| Supported Metal Catalysts (Pt/TiO₂, V₂O₅/TiO₂) | Model systems for surface reaction studies | CO oxidation, Hg⁰ oxidation mechanistic investigations [24] |

| Porous Supports (γ-Al₂O₃, MCM-41, Zeolites) | High surface area platforms with controlled porosity | Maximizing active sites, studying diffusion effects in L-H kinetics [1] |

| Promoter Compounds (Alkali metals, Al₂O₃) | Modify catalyst activity and selectivity | Enhancing N₂ dissociation in ammonia synthesis (L-H), altering selectivity [1] |

| Catalyst Poisons (S, Cl compounds) | Selectively block active sites | Mechanistic studies by selective site poisoning, understanding active site requirements [1] |

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Modern mechanistic studies employ sophisticated characterization methods to discriminate between L-H and E-R pathways:

In-situ Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFTS): Enables real-time monitoring of surface species during reaction, confirming coexistence of adsorbed reactants for L-H or absence of adsorbed B for E-R mechanisms [24].

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM): Allows direct observation of reactions at solid-gas interfaces in real space, providing visual evidence of mechanistic pathways [22].

Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD): Quantifies adsorption strength and surface coverage, essential parameters for kinetic modeling of both mechanisms.

Solid-State NMR (ssNMR): Probes atomic-level local structures of catalytic sites, their intrinsic reactivity, and site-site proximities relevant to L-H requirements [21].

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Determines surface composition and oxidation states during reaction, identifying adsorbed species.

Microkinetic Modeling with DFT: Computational approach combining density functional theory with kinetic analysis to simulate reaction pathways and discriminate between mechanisms [24].

Experimental Protocol for Mechanistic Discrimination

A standardized experimental approach for distinguishing L-H and E-R mechanisms:

Pre-adsorption Phase: Expose catalyst to reactant A alone, allowing adsorption to equilibrium while monitoring surface coverage.

Reaction Initiation: Introduce reactant B under controlled conditions, with and without continuous supply of A in gas phase.

In-situ Monitoring: Track surface species using DRIFTS and gas-phase composition using mass spectrometry simultaneously.

Coverage Variation: Systematically vary initial coverage of A while measuring initial rates of product formation.

Parameter Extraction: Determine reaction orders with respect to both reactants across concentration ranges.

Validation: Compare adsorption constants from kinetic and equilibrium measurements, with agreement supporting L-H mechanism.

This protocol leverages the fundamental distinction that L-H requires both species to be adsorbed, while E-R involves direct reaction with a gas-phase molecule, enabling clear mechanistic assignment through controlled experimentation.

The Langmuir-Hinshelwood and Eley-Rideal mechanisms represent two fundamentally distinct pathways for heterogeneous catalytic reactions, with the former requiring both reactants to adsorb and achieve thermal equilibrium with the surface before reacting, while the latter involves direct reaction between an adsorbed species and a gas-phase molecule. While many heterogeneously catalyzed reactions follow the Langmuir-Hinshelwood model [1], the Eley-Rideal mechanism remains critically important in specific systems, particularly in environmental catalysis such as mercury oxidation [24]. Proper discrimination between these mechanisms requires comprehensive experimental approaches combining kinetic analysis, adsorption studies, and in-situ spectroscopic characterization. As catalytic science advances with emerging techniques like machine learning potentials and higher-resolution in-situ methods [26], our understanding of these fundamental reaction pathways continues to refine, enabling more precise catalyst design and optimization for industrial applications across chemical production, energy conversion, and environmental protection.

The Sabatier principle stands as a foundational concept in heterogeneous catalysis, providing a critical framework for understanding and designing efficient catalysts. This principle articulates that for a catalyst to be effective, its interaction with reactant molecules must be "just right"—neither too strong nor too weak. This qualitative insight has evolved into a quantitative predictive tool that guides catalyst development across diverse fields, including thermal heterogeneous catalysis, electrocatalysis, and biocatalysis. Within the broader terminology of catalysis research, the Sabatier principle provides the thermodynamic basis for understanding why maximum catalytic activity occurs at intermediate binding strengths, a relationship visually captured in the characteristic "volcano plot" that maps activity against catalyst properties.

This guide explores the fundamental thermodynamic and kinetic aspects of the Sabatier principle, its experimental validation through volcano relationships, and modern computational approaches that leverage this principle for catalyst design. It further examines the concept of catalytic resonance as a strategy to overcome Sabatier limitations and details experimental methodologies for measuring catalytic turnover. Together, these concepts form an essential toolkit for researchers and scientists engaged in catalyst development and optimization.

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundation

The Fundamental Sabatier Principle

The Sabatier principle, named after French chemist Paul Sabatier, serves as a qualitative guide in heterogeneous catalysis. It states that the interactions between a catalyst surface and reactant molecules should be of intermediate strength to maximize catalytic efficiency. This balance is crucial because:

- If the catalyst-reactant interaction is too weak, reactant molecules fail to bind effectively to the catalytic surface, resulting in insufficient activation and minimal reaction rates.

- If the interaction is too strong, the reaction products (or intermediates) become immobilized on the catalyst surface, blocking active sites and preventing further turnover in a phenomenon known as catalyst poisoning [27].

This principle finds mathematical expression in volcano plots, which graphically represent the relationship between catalytic activity and a descriptor of catalyst-adsorbate binding strength, such as the heat of adsorption or formation of surface intermediates. These plots characteristically show activity increasing to a maximum at intermediate binding strengths before declining at stronger interactions, forming an inverted V-shape reminiscent of a volcano [27]. For example, in the catalytic decomposition of formic acid, a volcano relationship emerges when plotting reaction temperature against the heat of formation of metal formate intermediates, with platinum group metals occupying the peak position [27].

Thermodynamic Interpretation and Free-Energy Landscapes

Modern computational approaches have transformed the Sabatier principle from a qualitative concept into a quantitative predictive framework. For electrocatalytic reactions, this interpretation centers on mapping the free-energy landscape of reaction pathways.

In a typical two-step electrocatalytic reaction with one reaction intermediate, the catalyst's role is to optimize the free energies of all states along the reaction coordinate. The ideal catalyst achieves thermoneutral bonding, where the reaction intermediate has approximately the same free energy as both reactants and products at equilibrium potential (ΔG~RI~ = 0) [28]. This thermodynamic interpretation enables calculation of the thermodynamic overpotential (η~TD~), defined as the minimum overpotential required to make all elementary steps exergonic or thermoneutral. For a two-step reaction, η~TD~ = |ΔG~RI~|/e, where e represents the elementary charge, making a thermoneutral landscape (ΔG~RI~ = 0) the condition for zero overpotential [28].

Table 1: Thermodynamic Scenarios in Electrocatalysis Based on the Sabatier Principle

| Binding Strength | Free Energy of Intermediate (ΔG~RI~) | Rate-Limiting Step | Thermodynamic Overpotential (η~TD~) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Too Weak | > 0 (Endergonic) | Adsorption/Activation | > 0 V |

| Ideal (Thermoneutral) | ≈ 0 | Balanced | ≈ 0 V |

| Too Strong | < 0 (Exergonic) | Desorption | > 0 V |

Extensions and Modern Applications

Catalytic Resonance: Overcoming the Sabatier Limit

While static catalysts face fundamental limitations under the Sabatier principle, recent research demonstrates that dynamic catalysts can surpass these constraints through catalytic resonance. This approach involves systematically modulating catalyst properties, such as surface binding energy, between strong and weak binding states rather than maintaining a static intermediate state [29].

Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that when a dynamic catalyst oscillates at an optimal frequency that matches the intrinsic timescale of the surface reaction, a resonance effect occurs that dramatically enhances catalytic turnover. Studies show this approach can boost turnover rates by up to three orders of magnitude compared to optimal static catalysts [29]. This resonance phenomenon represents a fundamental shift from traditional catalysis design, introducing temporal control as a critical dimension for optimizing catalytic systems.

The practical implementation of catalytic resonance has been demonstrated in complex reactions such as electrocatalytic propane oxidation. By applying alternating potentials that individually optimize adsorption and oxidation steps—processes that typically require mutually exclusive optimal potentials under static conditions—researchers achieved significantly higher oxidation rates than possible under constant-potential operation [30]. This dynamic approach effectively decouples traditionally competing steps in the catalytic cycle, enabling each to proceed at its respective optimal condition.

Sabatier Principle in Biocatalysis and Electrocatalysis

The applicability of the Sabatier principle extends beyond traditional thermal heterogeneous catalysis into specialized domains:

In biocatalysis, recent research has established that self-sufficient heterogeneous biocatalysts (ssHBs)—where enzymes and cofactors are co-immobilized on the same support—obey the Sabatier principle. These systems achieve maximum catalytic efficiency at intermediate cofactor-polymer binding strength, with experimental data exhibiting characteristic volcano plots when activity is plotted against binding strength. Adjusting parameters like pH and ionic strength modulates these interactions, enabling optimization of biocatalytic performance [31] [32].

In electrocatalysis, the Sabatier principle provides the fundamental basis for catalyst design, particularly for energy conversion reactions critical to sustainable technologies. The widespread availability of density functional theory (DFT) calculations has made binding energy evaluation a routine practice, enabling computational screening of potential electrocatalysts before experimental validation [28]. This computational approach has been successfully applied to reactions including hydrogen evolution, oxygen reduction, and carbon dioxide reduction.

Table 2: Manifestations of the Sabatier Principle Across Catalytic Domains

| Catalytic Domain | Reaction Example | Binding Strength Descriptor | Optimal Catalyst Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Heterogeneous Catalysis | Formic Acid Decomposition | Heat of Formation of Metal Formate | Platinum Group Metals [27] |

| Electrocatalysis | Hydrogen Evolution Reaction | Hydrogen Adsorption Free Energy (ΔG~H~) | Platinum (ΔG~H~ ≈ 0) [28] |

| Biocatalysis | Redox Biotransformations | Cofactor-Polymer Binding Strength | Intermediate Binding Strength [31] [32] |

| Dynamic Catalysis | Propane Oxidation | Oscillation Between Strong and Weak States | Potential-Modulated Platinum [30] |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Computational Approaches: Density Functional Theory and Molecular Dynamics

Modern computational methods have revolutionized the application of the Sabatier principle in catalyst design:

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations enable quantitative prediction of adsorption energies and reaction pathways, providing the descriptor values needed to construct volcano relationships. The computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) model allows researchers to calculate the free energy landscape of electrocatalytic reactions, including the effect of applied potential [28]. These approaches have become standard practice for in silico catalyst screening, significantly reducing the experimental parameter space that must be explored.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation methods have been developed to study dynamic catalytic systems and resonance effects. These simulations introduce a classical model for surface reactions with time-dependent binding energy and employ non-equilibrium molecular dynamics where reactants are systematically added and products removed to simulate multiple catalytic cycles [29]. This approach can identify optimal modulation frequencies, amplitudes, and waveforms for programmable catalysts, providing molecular-scale insights into dynamic catalytic phenomena.

Experimental Protocols for Measuring Catalytic Turnover

Experimental validation of catalytic performance requires precise measurement of turnover frequency, defined as the number of reaction events per catalytic site per unit time. The following protocol for studying electrocatalytic propane oxidation illustrates key methodological considerations:

Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (EC-MS) Setup: Researchers employ a thin-layer electrochemical cell coupled to a mass spectrometer for simultaneous electrochemical measurement and product quantification. The system uses platinized platinum working electrodes, standard reference electrodes (e.g., SHE), and counter electrodes in 1 M HClO~4~ electrolyte at 60°C [30].

Electrode Pretreatment Protocol:

- Clean electrode by applying 1.4 V for 20 seconds

- Apply 0.05 V for 20 seconds

- Repeat this cycle three times total

- Hold at 0.05 V to establish MS baseline [30]

Turnover Rate Measurement Procedure:

- Initiate reactant adsorption at 0.3 V for 60-900 seconds

- Apply constant oxidation potential (E~turnover~) from 0.4-1.1 V for 360 seconds in propane-saturated electrolyte

- Quantify CO~2~ production via m/z 16 signal using mass spectrometry

- Step potential to 0.3 V to halt oxidation and monitor CO~2~ signal decay to baseline

- Calculate propane consumption using stoichiometry of total oxidation (C~3~H~8~ + 5O~2~ → 3CO~2~ + 4H~2~O) [30]

Data Analysis: Linear regression of propane consumption versus time yields potential-dependent turnover rates, revealing the optimal potential window for maximum activity (0.5-0.8 V for propane oxidation on Pt) [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Sabatier Principle and Turnover Studies

| Material/Reagent | Specifications | Functional Role | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platinized Platinum Electrode | Polycrystalline, high surface area | Working electrode for catalytic reactions | Propane oxidation studies [30] |

| Computational Hydrogen Electrode (CHE) Model | DFT-based computational framework | Calculating free energy landscapes | Predicting catalyst activity [28] |

| Perchloric Acid Electrolyte | 1 M concentration, high purity | Proton-conducting medium | Electrocatalytic oxidation [30] |

| Cationic Polymer Coating | e.g., Polyethylenimine derivatives | Cofactor immobilization | Self-sufficient biocatalysts [31] [32] |

| Porous Agarose Support | Functionalized with cationic polymers | Enzyme and cofactor immobilization | Heterogeneous biocatalysts [31] |

| Mass Spectrometer | Electrochemical coupling capability | Product quantification and identification | Measuring CO~2~ evolution rates [30] |

The Sabatier principle remains a cornerstone of heterogeneous catalysis, providing an essential framework for understanding the relationship between catalyst-adsorbate binding strength and catalytic activity. Its manifestation in volcano plots offers a powerful tool for visualizing and optimizing catalyst performance across diverse applications, from industrial chemical synthesis to energy conversion technologies. While the principle establishes fundamental limitations for static catalysts, emerging approaches like catalytic resonance demonstrate how dynamic modulation of catalyst properties can transcend these constraints.

The integration of computational methods, particularly density functional theory and molecular dynamics simulations, with sophisticated experimental techniques such as electrochemical mass spectrometry has transformed the Sabatier principle from a qualitative concept into a quantitative predictive framework. This synergy enables researchers to systematically explore catalytic mechanisms, identify rate-limiting steps, and design optimized catalysts with precisely tuned binding properties. As catalysis research continues to address challenges in sustainable energy and chemical synthesis, the principles outlined in this guide will remain essential for the rational design of next-generation catalytic systems.

Catalyst Design, Characterization Methods, and Applications in Biomedical Research

Catalyst synthesis represents a cornerstone of modern chemical research, enabling the production of materials with tailored properties for applications ranging from large-scale chemical manufacturing to pharmaceutical development. Within heterogeneous catalysis, the strategic design of catalytic active sites—whether as nanoparticles, nanoalloys, or supported systems—directly governs critical performance metrics including activity, selectivity, and stability [33] [4]. The evolution from simple monometallic particles to sophisticated multi-element architectures with controlled interfaces has unlocked unprecedented catalytic capabilities [34] [35]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary synthesis methodologies, emphasizing the precise control over structural parameters that dictate catalytic performance. By establishing correlations between synthetic strategies and resultant catalyst properties, this resource aims to equip researchers with the fundamental knowledge required to design and implement advanced catalytic systems for specialized applications.

Fundamental Principles of Catalyst Design

The efficacy of a heterogeneous catalyst is governed by the interplay of several foundational principles. The Sabatier principle establishes that optimal catalytic activity requires an intermediate strength of interaction between the catalyst surface and reactant molecules; bonds that are too weak fail to activate reactants, while bonds that are too strong lead to product poisoning [1] [4]. This principle manifests quantitatively in volcano plots that correlate activity with adsorption energies.